Intertestamental Period Info

advertisement

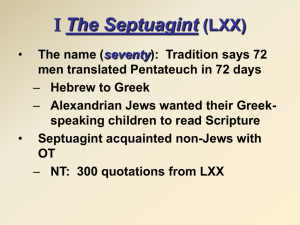

Intertestamental Period: Many things mentioned in the New Testament, especially the Gospels and the book of Acts, find their roots in the 400 years between the Testaments. For instance, (1) the family of king Herod (Matthew 2:1, 22); (2) the Jewish Sanhedrin—Jewish Supreme Court (Luke 22:66); (3) the religious sectarian groups such as the Scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees (Matthew 2:4; 3:7) along with their religious ideas, traditions and practices (Matthew 25:1-2; 23; Acts 23:8). Then there were (4) political and militaristic groups such as the Herodians (Matthew 22:16) and the Zealots (one of Jesus’ apostles had formerly been a Zealot—“Simon called the Zealot” (Luke 6:15). Of course (5) the Roman Empire which took over Palestine during Intertestament times (63 B.C.) was still in power throughout the New Testament era (Luke 2:1; 3:1; John 11:48). The Intertestamental Period was in a sense a period of preparation for the coming of Jesus, the Christ. He came, says Paul, “when the fullness of the time had come . . .” (Galatians 4:4-5). During the 400 years between the Testaments God was at work preparing for that time when His Son, Jesus Christ, would step out of eternity into time. Note the following preparations which led to the “fullness of the time.” There was the preparing of the way through the Greek language. Alexander the Great conquered the Mediterranean world and the near east (334–323 B.C.) in a cultural sense as well as militarily. One very important aspect of Greek culture was the Greek language. After Alexander, the Greek language gradually became the language used everywhere. The Old Testament Scriptures were translated into Greek in Egypt between 250 and 100 B.C. This translation known as the Septuagint was used by Jews scattered over the Mediterranean world who were losing their ability to speak Hebrew. In the providence of God the gospel was spread to Jews and pagans in the Greek language. Also, the whole New Testament was originally written in Greek. There was the preparing of the way through Roman political power. The Roman Empire brought a number of positive things which made the spread of the gospel a reality. For one thing, the Romans built a vast system of excellently made roads throughout the empire. Preachers of the gospel, like Paul, took advantage of these roads to enable them to move swiftly and with ease to their destinations. Never were circumstances better or more favorable for the proclamation of the gospel. The fact that Rome had its armies stationed throughout the empire to insure the law and order for which they were famous was a plus to the growth of Christianity. There was the preparing of the way through the Hebrew religion. During Intertestamental times Judaism developed into a highly legalistic system. This legalism continued on into New Testament times with great vigor. Legalism is man’s attempt to make himself acceptable to God on the basis of self effort (law keeping). It is illustrated in the Gospels in the various encounters Jesus had with the Scribes and Pharisees (see the teaching of Jesus, for instance, in Matthew 15). Legalism was Jesus’ most formidable obstacle to overcome in Judaism. However, what positive things did the Hebrew religion contribute? The answer is simple. The Hebrew religion centered around the truth of monotheism (one God), and the Law of Moses. Wherever the Jews went in the dispersion they took these two foundational truths. Paul took advantage of this ideal situation when he went on his missionary journeys. How? He would always go to the Jews first, at the synagogue, using what truth they did know as a springboard to preach the gospel. XII. ISRAEL'S INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD - (Judah under the domination of Persia, Greece, and Rome; Daniel 2:39,40; 7:5-7; 8; 11; ca. 400-5 B.C.) For about 400 years, Israel was without any prophetic voice aside from the books of the OT. During this time, Israel enjoyed peace under Persian rule (400-332 B.C.), then a period of increasing hostilities as the Syrian and Egyptian remnants of Alexander the Great's Greek empire fought over Palestine (332-142 B.C.), a brief period of self-rule under the Hasmonean priest-governors (142-63 B.C.), and finally Roman control after Pompey entered Jerusalem in 63 B.C. During this period, the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Herodians, and synagogues develop, along with the emergence of a great deal of apocryphal and pseudepigraphical Jewish literature. Question: "What happened in the intertestamental period?" Answer: The time between the last writings of the Old Testament and the appearance of Christ is known as the “intertestamental” (or “between the testaments”) period. Because there was no prophetic word from God during this period, some refer to it as the “400 silent years.” The political, religious, and social atmosphere of Palestine changed significantly during this period. Much of what happened was predicted by the prophet Daniel. (See Daniel chapters 2, 7, 8, and 11 and compare to historical events.) Israel was under the control of the Persian Empire from about 532-332 B.C. The Persians allowed the Jews to practice their religion with little interference. They were even allowed to rebuild and worship at the temple (2 Chronicles 36:22-23; Ezra 1:1-4). This period included the last 100 years of the Old Testament period and about the first 100 years of the intertestamental period. This time of relative peace and contentment was just the calm before the storm. Alexander the Great defeated Darius of Persia, bringing Greek rule to the world. Alexander was a student of Aristotle and was well educated in Greek philosophy and politics. He required that Greek culture be promoted in every land that he conquered. As a result, the Hebrew Old Testament was translated into Greek, becoming the translation known as the Septuagint. Most of the New Testament references to Old Testament Scripture use the Septuagint phrasing. Alexander did allow religious freedom for the Jews, though he still strongly promoted Greek lifestyles. This was not a good turn of events for Israel since the Greek culture was very worldly, humanistic, and ungodly. After Alexander died, Judea was ruled by a series of successors, culminating in Antiochus Epiphanes. Antiochus did far more than refuse religious freedom to the Jews. Around 167 B.C., he overthrew the rightful line of the priesthood and desecrated the temple, defiling it with unclean animals and a pagan altar (see Mark 13:14). This was the religious equivalent of rape. Eventually, Jewish resistance to Antiochus restored the rightful priests and rescued the temple. The period that followed was one of war, violence, and infighting. Around 63 B.C., Pompey of Rome conquered Palestine, putting all of Judea under control of the Caesars. This eventually led to Herod being made king of Judea by the Roman emperor and senate. This would be the nation that taxed and controlled the Jews, and eventually executed the Messiah on a Roman cross. Roman, Greek, and Hebrew cultures were now mixed together in Judea. During the span of the Greek and Roman occupations, two important political/religious groups emerged in Palestine. The Pharisees added to the Law of Moses through oral tradition and eventually considered their own laws more important than God’s (see Mark 7:1-23). While Christ’s teachings often agreed with the Pharisees, He railed against their hollow legalism and lack of compassion. The Sadducees represented the aristocrats and the wealthy. The Sadducees, who wielded power through the Sanhedrin, rejected all but the Mosaic books of the Old Testament. They refused to believe in resurrection and were generally shadows of the Greeks, whom they greatly admired. This rush of events that set the stage for Christ had a profound impact on the Jewish people. Both Jews and pagans from other nations were becoming dissatisfied with religion. The pagans were beginning to question the validity of polytheism. Romans and Greeks were drawn from their mythologies towards Hebrew Scriptures, now easily readable in Greek or Latin. The Jews, however, were despondent. Once again, they were conquered, oppressed, and polluted. Hope was running low; faith was even lower. They were convinced that now the only thing that could save them and their faith was the appearance of the Messiah. The New Testament tells the story of how hope came, not only for the Jews, but for the entire world. Christ’s fulfillment of prophecy was anticipated and recognized by many who sought Him out. The stories of the Roman centurion, the wise men, and the Pharisee Nicodemus show how Jesus was recognized as the Messiah by those who lived in His day. The “400 years of silence” were broken by the greatest story ever told—the gospel of Jesus Christ! 8 Between the Testaments: 400 B.C.E. to Jesus A four-hundred year gap exists between the last events of the Old Testament and the time of Jesus. Our knowledge of those centuries is sparse. The only canonical exception to this silent period is the book of DANIEL, written around 170 B.C.E. in the midst of one of the biggest challenges to the faith of Israel in the intertestamental period. Fortunately, the Apocrypha (especially the book of 1 MACCABEES), the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (Jewish writings from this period of time that were never canonized), and the Dead Sea Scrolls (which date from the second century B.C.E. to the first century C.E.) provide helpful windows on this time period. Three main events dominated this period and their repercussions were extensive. First, Alexander the Great conquered the huge territory ranging from Greece in the West to Pakistan in the East, including Palestine (around 333 B.C.E.) and Egypt. Along with his military conquests came the spread of Greek language and culture. This spreading influence, known as Hellenism, is not unlike the spread of American culture around the world today. Along with the spread of Greek language and culture came the spread of Greek religion. But how should the faithful Jew respond to this new culture, language, and religion? Should it be resisted? Should it be embraced (the answer of the "Letter to Aristeas" in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha)? Should part of it be embraced and part of it resisted? Conservative Jews resented pagan Hellenism and agreed that its spread must be resisted. But how? Should they take up arms (the answer of 1 Enoch and 1 MACCABEES) or should they resist nonviolently (the answer of DANIEL)? When the Seleucid Antiochus IV "Epiphanes" (a self-imposed nickname meaning "God manifest"), took the throne of Syria and Palestine in 175 B.C.E., he decided to be more intentional and consistent about the "Hellenization" of his subjects than ever before. He made it illegal to offer sacrifices to Yahweh in the Temple or to circumcise a baby. In short, he outlawed Judaism. He went so far as to "desecrate" the Temple in Jerusalem by marching into the Holy of Holies (where only the high priest was to enter, and then only once a year on the Day of Atonement), and proceeded to sacrifice a pig (ritually unclean to the Jews) on the altar to his god, Baal Shemesh, or Zeus. As a result, the Jews revolted. This Maccabean Revolt was the second important event. After about twenty-five years of fighting, the Jews gained independence from what was left of the Greek empire. Their independence under a group of Jewish rulers called the Hasmoneans lasted from 142 to 63 B.C.E. That eighty-year period was the first since 586 B.C.E.-and the last until 1948 C.E.-that Jewish leaders had control over their own land. Although this revolt began with high motives to provide a kingdom in which Yahweh could be worshipped properly without interference from foreign influence, the Hasmonean dynasty soon deteriorated into a typical Hellenistic tyranny, complete with its own paranoid and cut-throat power politics, including the murder by Jews of fellow Jews who criticized Hasmonean policies. When a dispute arose in the 60s about who would be the next legitimate Hasmonean king, the Romans stepped in to restore orderly government. However, that "rescue" in 63 B.C.E. came at a high cost: the Jewish people were again put under foreign domination. In the meantime, the form of religious faith called Judaism, which had roots going back to Ezra, continued to grow and develop. The twin emphases of keeping the Law and observing the temple rituals, with its calendar of festivals, characterized this movement of Jewish religion as different from Israel's earlier faith. Accompanying and spurring these emphases was the rise of the synagogue as a local place of worship and instruction in the Law. In the second century B.C.E., several Jewish religious "parties" developed around differing visions about how God's people should understand and maintain their identity. Immediately below the surface of the identity question was the issue of how and how much faithful Jews should resist Hellenism. The resulting "parties" consisted of the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Essenes, and the Zealots. The Sadducees were a priestly, aristocratic group that ran the Temple establishment, held public offices, and cooperated with the Roman overlords. They were the conservative "establishment" group who advocated compromise and acceptance of Hellenism-as long as their system of Temple worship was not threatened. This group had perhaps the most to gain from cooperating with the Romans: not only continued control of the Temple, but also the high standard of living deriving from their Temple activities. For the Sadducees, the Torah alone-the first five books-were authoritative. The Prophets were perhaps interesting, but not ultimately useful for determining doctrine. The Pharisees were a nonpriestly or lay group that took the keeping of the Law, in both written and oral forms, very seriously. The "oral law" allowed them to adapt the written Law to changing circumstances. They advocated a clear and courageous resistance to Hellenism, but not organized, violent resistance. The Pharisees were optimistic about the possibility of complete faithfulness to God-if one were fully committed to it. They also tended to look down on the common person who could not afford all the sacrifices required for "full compliance" to the Law of Moses. The Essenes were convinced that everyone else was lax, if not evil. The Essenes were a priestly group whose origins stemmed from the second century B.C.E. when a new line of priests took control of the Temple. The Essenes believed that of all the Jews, only they were acceptable to God. As a result, they withdrew into separated communities, such as the community at Qumran near the Dead Sea. They were very rigid in observing the Law-especially laws concerning purity and the religious calendar- and looked forward to the Day of the Lord in which they would serve as soldiers in God's final war. (One of the Dead Sea Scrolls even contains detailed instructions for how to fight in this Final Battle.) The Zealots represented a fourth option. It is questionable whether a continuous, organized movement of Zealots existed from 167 B.C.E. to 66 C.E., when the Zealots led the First Jewish Revolt against Rome; "Zealotism" was, after all, illegal, and its adherents were forced "underground." Nevertheless, "Zealotism" remained a clear and present theoretical option to Jews and throughout this period, several Zealot leaders and movements arose. These Zealots advocated bold and violent resistance to the evils of pagan Hellenism, even if it meant death, for in their view, their own resistance was a continuation of the Maccabean concern to "throw out the pagan foreigners." Prominent in the diverse forms of Judaism at the turn of the millennia was apocalyptic thought. Sometimes apocalypticism took a revolutionary form, but it usually counseled waiting for the Lord to intervene in a cataclysmic way to defeat all evil forces and to set the world aright. Faithful Jews who held this viewpoint developed a literature using dramatic symbols and visions. Another school of thought was indebted to the wisdom tradition and developed a literature much like the wisdom literature of the Old Testament. The book of DANIEL, which probably comes from this period, includes both of these viewpoints-wisdom and apocalyptic. The Apocrypha and other writings not included in the Jewish or Christian canons (the "Old Testament Pseudepigrapha") were products of this era. The Apocrypha contains history and wisdom literature, while the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha also contains apocalyptic writings.