speech - WordPress.com

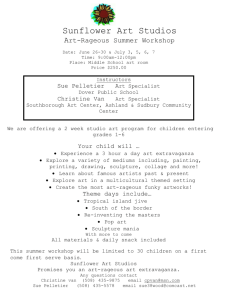

advertisement

Keynote speech by Matt Hongoltz-Hetling, co-Journalist of the Year 2012, at 2013 Hall of Fame induction luncheon: So, I thought I’d share a recent experience I had with you. I was doing one of those very typical traffic accident stories this May, based on a news release from the State Police. Fatal car accident. 62-year-old man from New Sharon, who pulled out of his driveway onto a busy road, Route 2, and into the path of a tractor trailer. The man was rushed to Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston, where he died the next day. I wrote it up without a lot of thought. I reported the name of the man driving the tractor trailer, who was not charged. I quoted police saying alcohol was being considered as a possible cause, meaning that the dead man, John Pelletier, might have been drinking. I included those other stupid details we put in the news just because they’re available, like the year and model of the tractor trailer, the type of pickup truck Pelletier was driving when he died. Once it was published, my editor fielded a call from a family member who complained about the story, and denied Pelletier was drunk, which is fairly typical, and my editor defended the right of the paper to print such a thing, our usual response. So, I followed on the story, touched base with the police a few times to see what the final determination was, and in July, the toxicology report showed alcohol was not a factor. So I wrote a second story and reported on the new most likely cause, “driver inattention.” Almost six weeks later, the end of August, I got the following email. It has a tone that I’m sure we’re all familiar with. It starts: Hey dipshit, This is my uncle you are writing about and I would really appreciate it if you would take your job seriously and write the truth. He was an ass at times and he liked his beer, but he meant a lot to me when I was a kid. Your initial report smeared him by saying alcohol was involved --thus pissing on his memory to anyone that read it. Just to make a headline more interesting. He never drove drunk to my knowledge and he was crippled with disabilities. Go back to school or at least DO YOUR JOB. Instead of sensationalized reporting. And then he signed it and gave his name. I try to respond to every letter I get from someone who’s read my story. Sometimes it’s easier to know what to say back than other times. Here’s what I settled on: Hi, I understand that a lot of your abrasiveness here is a byproduct of the pain that you and your family are going through because of the death of your uncle, so I won’t hold that against you. I’m very sorry for the loss, and I’ll try to give you some insight into why the stories contained the information they did. I then went on to talk about public information, and reporting on what the police say, and all that jazz. Then, at the end, I wrote: Again, I’m sorry for your loss, and if there are any factual errors in any of my articles, please let me know so that I can correct them. That email led to a conversation between me and the letter writer’s mother, in which I heard her take on what happened to John Pelletier. They told me about how, when John Pelletier was young, he had a beautiful lakeside home, and a degree in veterinary medicine, and a wife and child, and a great sense of humor, and a promising future. In 1981, when he was 30 years old, he was struck by a drunk driver. The 1981 accident nearly killed him, left him disfigured, brain damaged. He tried to go back to work, but couldn’t, in part because his hand functioned like a claw. He lost everything – his wife left him, he lost the house, he had emotional issues related to the brain damage. Everything in his life was bad after that. He wound up in a broken-down trailer in New Sharon, where his best friend was his car mechanic. The mechanic told me, “I wouldn’t really call him a friend.” And so this man, whose life had been ruined by a drunk driving accident that was no fault of his own, died tragically 32 years later in another accident. His family said his disabilities – the bad hand, some visual impairments – may have caused the accident that killed him this year in New Sharon. And after he died, he was called a drunk driver himself. In the newspaper. By me. When I was in college, in a class on philosophy or maybe it was political theory, there was this idea that kings are like giants. I tried to look up the source of that idea, but when you Google kings and giants, you get a bunch of sports stuff. But I remember the idea, that monarchs and other heads of state can change the whole world, destroy a whole village with an inadvertent twitch or footstep, that idea really stuck with me. In order to do our job, and to do it well, we have to be hard-hearted sometimes. We have to close our ears to criticism, to accept that people will be angered by some of the things we write, and to remember that we serve a higher cause, the truth, and that the truth sometimes hurts. In the service of the truth, to protect ourselves from the pain that comes with those criticisms, it can be easy to look down on the people who insult and attack us for doing our job. But I try to remember and live by a quote from another philosopher, Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. Twain said, “I never met a man so stupid that I couldn’t learn something from him.” In this age, when we are awash in information, we all have to sort through a lot of bathwater to find those babies. And when we’re on the clock, we have to do that efficiently. But while we’re often reminded to afflict the comfortable, we can’t forget the other part of that great maxim, to comfort the afflicted. To me, that means giving five minutes of our time to those who come in, from the politically connected businessman who tries to manipulate our coverage, to the slurring drunk who wants to complain about his most recent arrest, to the grieving family member who was hurt by some routine crime or traffic story we wrote. My final story on John Pelletier covered the entire sweep of his life, from his time as a child in Fort Kent, to the day his ashes were scattered over the Allagash. I talked to his mechanic, I referred to old newspaper stories, and I tied his personal story into some drunk driving statistics and a change to state drunk driving laws that will go into effect on December 1. That story, the story of John Pelletier’s life, was the one that mattered. It generated a ton of web traffic. We all know that, for every dozen stories we write that we get no feedback on, there is one story we get a dozen emails and phone calls on, and that was one of those stories. It’s a reminder that if we want people to care about a story, it’s got to tell a story. Our industry is in a state of flux. 100 years from now, the Maine State Newspaper Historian will look back at these years and describe them as a time of crisis for Maine’s newspapers. We cannot beat the Internet, and so we have decided to join it, but the problem is the Internet doesn’t think we’re special enough to pay us at the rates to which we’ve become accustomed. The historian will look at the leaders of our publications from this decade, and tell stories about which of them crumbled under pressure, and which of them seized the opportunity to right the ship. I like the Maine newspaper historian from 2113. He’s old, as all historians are, and nobody listens to him, partly because he’s passionate about something very few people care about, and partly because his breath smells like tuna, but that’s because he eats a lot of tuna to support the Press Herald’s tuna sales division, which supplements the news department of the future. They also don’t like that he reads the newspaper with those antique Google glasses, while the rest of them just have the knowledge uploaded into their neural implants, like a normal person. What I like most about him, though, is that he respects the news industry stories he knows, and he respects the people in them. He respects us and wants to judge us fairly. I want to be like that— to respect the stories of the people I write about. I know we must be hard sometimes, but we must also be soft sometimes, human. Knowing when to do which is one of the keys to being a good reporter, and to being a good person. We in the newspaper business are not kings. You only have to look at our paychecks to know that. But we do have power, to hurt, to help, to heal, to harass. When we are aggravated and make hasty decisions, people – real people – are harmed. And when we make the right decisions, those people benefit. Today, we’re here to celebrate the members and new inductees of the Hall of Fame – Don Hansen, Scott Haskell, Emery Labbe. They are giants among giants whose actions influenced, not only the public, but the rest of us who pay attention to the things that they do because we have faith that they are worth emulating. They have all shown compassion, and they have all made it to the Hall of Fame. Let’s continue to follow in their footsteps.