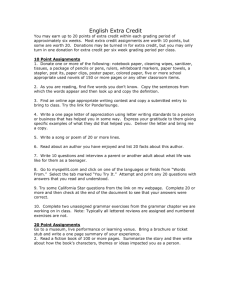

Preparing and evaluating writing assignments 1

advertisement

Preparing and evaluating writing assignments Juldyz Smagulova, May 2005 Problems Instructors often complain that students don’t know what the teacher wants. Instructors of writing-intensive courses often list the work involved with commenting on student drafts-inprogress among their chief concerns. First, they point out, they are not trained as teachers of writing. Some have never before assigned writing activities of any kind. Second, they tell that commenting takes endless acres of time and may not do any good. Students often complain that they don't know what the teacher wants. Even though we may be quite explicit in describing the writing assignment, students will tend to forget details unless the assignment is in print and unless the assignment sheet specifies all the requirements. Characteristics of Effective Writing Assignments • Assignments are provided and explained in writing Announce your writing assignments in the course syllabus, and explain the weighting course writings will have in the calculation of course grades. But follow up the syllabus announcement by spelling out your particular aims for writing assignments in separate handouts for each assignment. • Writing assignments are linked to significant course objectives Students will take integrated writing assignments more seriously than those that seem merely supplementary. • Notices of assignments specify the kind and purpose for writing, the audience to be addressed, the mode or form of the writing, and its length Your rationale for the assignment will help to make the writing more meaningful for students. Your expectations for their performance can engage them early in self-assessment of their work. Models of the forms and modes of writing you expect can help students to work more efficiently. And your specifications of the length of the writing help students better plan their writing projects. Characteristics of Effective Writing Assignments • Assessment criteria are specified How would you describe excellent student performance on your course writing assignment? How would you describe competent performance? Do you have a minimum standard below which papers would not be unacceptable? Criteria should specify the length requirements, the source or citation requirements (if appropriate), the documentation form expected (if appropriate), the formatting requirements • Due dates are specified Target dates for completion of drafts or sections, for critiques, and for final draft submission • Longer writing projects are organized in stages Shorter writing assignments can be paced across the semester. They may be tailored to follow topical progression of course content or increase gradually in sophistication as students develop competence in the subject. Longer assignments can be organized so that elements of the writing project or multiple drafts are submitted for evaluation and feedback in manageable increments. • • • • • Outline/structure of the paper is specified An example of model paper is provided Editing and style requirement specifications are given A peer critique guidelines developed Penalties for failing to meet basic requirements and deadlines Guiding Questions for Developing Assignments • How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course? • What learning or critical thinking do you expect students to do? • What elements of the "writing situation" should be reflected in the assignment? • What form should the writing take? • How can the writing process be segmented to enable feedback or additional instruction? • How will you assess the process and the final product? • What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study? Defining the writing task • Is the assignment sequenced so that students write a draft, receive feedback (from you or fellow students), and then revise it? • Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper's main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions? • What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, use certain skills, etc.)? • What is the required form (e.g., argumentative essay, report, business report)? • What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion)? Defining the audience for the paper • Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students. • What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? toward the student writer's thesis? toward the student writer? • What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers? Defining your evaluative criteria If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment's content: • • • • • • • • • • • • • organization focus critical thinking original thinking use of research logic appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument) format correct use of sources grammar and mechanics professional tone correct use of course-specific concepts and terms depth of coverage Sequencing Writing Assignments There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments: • sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course • it helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises • it encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives • it mirrors professional work in many professions. Sequencing writing assignments The concept of sequencing writing assignments allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, "sequencing an assignment" can mean establishing some sort of "official" check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments. Submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft. Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other's drafts. Require consultations. Have students consult with you about their prewriting and/or drafts and request that the Center inform you that such a visit was made. Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view. Sequencing writing assignments Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students' assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article). Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge. Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course. Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. Submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section). Types of Assignments • Formal or extended assignments These are longer papers that might involve doing research or making a well-supported and wellreasoned argument, require a specific format or style of presentation, clear and grammatical prose. Students need time for revision and editing. Grades for these types of writing projects are “higher stakes" • Shorter, less formal assignments These are usually one- to two-page assignments, often completed as homework. They might be part of a larger writing project or they might be isolated assignments. Sometimes these assignments are expected to be polished, correctly formatted, and grammatical. If so, time for revision should be included in the assignment schedule. At other times, shorter assignments resemble in-class writing, when the concern is primarily with content, not with "correct" presentation. Grades for these types of writing projects are "lower stakes," and students may undertake many such assignments during the term - perhaps one per week. • In-class writing These assignments are completed in class and are usually informal. Where the longer types of assignments often require students to produce finished, polished work, these ask students to brainstorm, freewrite, and/or respond to course materials. Of course, you may occasionally require that students complete focused and relatively polished in-class writing (on an essay exam, for instance). But more often, these assignments are intended to get students reading and thinking more deeply. Thus, we often refer to them as "write-to-learn" activities. The content of the work is more important than its grammar, style, and organization. Grades for these types of assignments reflect their informal nature. Some instructors don't grade informal writing at all they may just respond with written comments, or assign checkmarks for completed work. Selecting an Effective Writing Assignment Format In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions: Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students' understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., "pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln," or "pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church"). Selecting an Effective Writing Assignment Format Editorials. Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial. Cases. Students might create cases particular to the course's subject matter for other students to solve. Position Papers. Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay. Imitation of a Text. Students can create a new document "in the style of" a particular writer/organization. Instruction Manuals. Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process. Dialogues. Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal their theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., "Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art"). Collaborative projects. Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques. Evaluating Writing Assignments Formal writing assignments (i.e., compositions and essays) are graded on the following criteria. • Preparation and Editing. Has the writer used planning and editing guides as assigned? Has the writer presented information clearly? Has the writer carefully checked and corrected subject / verb agreements, adjective / noun agreements, and gender agreements on all drafts turned in? Has the writer carefully checked and corrected spelling (including accents) on all drafts turned in? • Vocabulary. Is the vocabulary sufficiently precise, elaborate, and appropriate for the topic, considering the course level? • Grammar and Syntax. Is the writer adequately applying the grammatical rules s/he has studied? Is the syntax sufficiently complex and French? Has the writer used French sentence structure learned so far, or do sentences seem to be translated directly from English into French? Do errors obscure meaning? • Content and Style. Has the writer understood and addressed the topic assigned? Is the content interesting and rich enough for the student's level? Is the topic addressed in sufficient depth and detail? Do sentences (paragraphs, ideas) flow logically? In specific writing genres (letters, essays, reviews, etc.), are specific organizational elements used appropriately (topic sentences, transitions, introductions, conclusions, salutations, etc.)? Does the writer show awareness of the real and/or implied reader's needs? Are tone and register appropriate to the writing sample and its reader? Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time 1) Use Peer Evaluation Distribute rubrics to students asking each to read and score three of his or her peers' essays in a specific amount of time. After grading an essay, they should staple the rubric to the back of it so as not to influence the next evaluator. If necessary, check off students who have completed the required number of evaluations; however, I have found that students do this willingly. Collect the essays, check off that they were completed on time, and return them to be revised. 2) Grade Holistically Use a single letter or number based on a rubric. To do this, put your pen down and simply read and sort assignments into piles according to score. When finished with a class, check each pile to see if they are consistent in quality, then write the score at the top. This allows you to grade a large number of papers quickly. It is best used with final drafts after students have used a rubric to grade one another's writing and made improvements. 3) Use Portfolios Have students create a portfolio of checked-off writing assignments from which they select the best to be graded. An alternative approach is to have the student select one of three consecutive essay assignments to be graded. Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time 4) Grade Only a Few from a Class Set - Roll the Die! Use a roll of a die to match numbers selected by students in order to select from eight to ten essays that you will be grading in-depth, checking off the others. 5) Grade Only a Few from a Class Set - Keep them Guessing! Tell students you will make an in-depth evaluation of a few essays from each class set and check off the others. Students will not know when theirs will be graded indepth. 6) Grade Only Part of the Assignment Grade only one paragraph of each essay in depth. Don't tell students ahead of time which paragraph it will be though. 7) Grade Only One or Two Elements Have students write at the top of their papers, "Evaluation for (element) " followed by a line for your grade for that element. It is helpful to also write "My estimate _____" and fill in their estimate their grade for that element. 8) Have Students Write in Journals Which Are Not Graded Require only that they write either for a specified amount of time, that they fill a specified amount of space, or that they write a specified number of words. Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time 9) Use Two Highlighters Grade writing assignments using only two colored highlighters with one color for strengths, and the other for errors. If a paper has many errors, mark only a couple you think the student should work on first so that you don't cause the student to give up. 10) In-class writing and revising Use in-class time modeling the writing and the RE-writing you want and how to meet your expectations. Do it together. Put a draft of the assignment you wrote up on an overhead and get their suggestions. Ask permission to use some of their papers (blind), put them on overheads and re-write as a class, with explicit references to your expectations and criteria. 11) Limit your comments on individual papers Rather, keep track of fairly common errors or strengths and then discuss these verbally with the whole class or distribute them to the class in a handout, or send them to all students via e-mail. Grading will go faster this way but students still get needed feedback. 12) Give highly structured assignments Specify a very detailed and explicit structure to some assignments (e.g., exact format, length, coverage, parts, order/organization, outline style) and require students to follow it. Grading of highly structured assignments goes much more quickly because it is easier to find what you are looking for and to spot errors and omissions. Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time 13) Spread writing activity over numerous assignments Responding to several three-page papers really is less time-consuming than responding to a stack of 15-page research papers. Working through a sequence of shorter assignments (and sets of comments) also provides students with opportunities to use your feedback to improve their writing 4) Ask students to reflect on their own work Save commenting time by getting students to articulate revisions that they already know about. Ask them, for example, to attach answers to the following questions directly to their drafts: What is your purpose in this paper? What do you know you need to revise? What would you like me to focus on? 15) Respond to content first Comments about content affirm the communicative function of writing. In fact, research has shown that comments are most effectively acted upon when they refer to the ideas or content that the writer is trying to convey. Asking a question about what a writer is saying ("Are you suggesting….?" "Do you mean….?" "I'd need more substantial evidence to be convinced of this..."), in other words, will be more useful than ten "Awk!" "No!" or "Huh?" comments. Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time 17) Remember to praise Comments like "I like the way you contrast only the principal ideas of these two schools of thought," or "Excellent choice of quotes here!" will affirm specific writerly moves and sustain student motivation. 18) Resist time-consuming copy-editing If mechanical and grammatical errors are substantial, consider marking up one page or one paragraph only. Point out patterns of error rather than noting each specific glitch. So long as you make clear to students that you aren't going to be noting every single error, you need not worry that students will assume that all unmarked writing is correct. 19) Talk to students When lengthy comments really are in order, time may be more effectively spent meeting with students to discuss their drafts in person. DO remember that students learn to write better by writing. THEY do not have to have feedback on all writing-the writing itself is what is important. Creating Grading Rubrics for Writing Assignments • Step One: Identifying criteria Developing assignment-specific objectives that are considered, prioritized, and reworded to create a rubric's criteria. Care must be taken to keep the list of criteria from becoming unwieldy; ten ranked items is usually the upper limit. In addition, to be usefully translated and used by students, criteria should be specific and descriptive. • Step Two: Weighing criteria When criteria have been identified, decisions are made about their varying importance. • Step Three: Describing levels of success When the criteria have been set, decisions must be made about an assessment scale (e.g., weak, satisfactory, strong; A,B,C,D, F, etc.). • Step Four: Creating and distributing the grid When the specific criteria and levels of success have been named and ranked, they can be sorted into a table and distributed with the assignment. Example 1=not present 2=needs extensive revision 3=satisfactory 4=strong 5=outstanding Insights and developments of ideas Address of target audience Organization and use of prescribed formats Integration of source materials Grammar and mechanics Comments: Final Grade: 1 2 3 4 5 Example Unaccept able Content •the depth of content •quality of argument •development of ideas Organization •overall and paragraph structure •coherence Clarity •readibility of the prose Correctness •grammar •mechanics •formatting Weak Average Strong Exceptional Numbers in parentheses are the possible point values for each associated grading criterion. (1)__________1. Spelling (remember to reread your paper before turning it in to pick up misspellings and typos) (1)__________2. Grammar (1)__________3. Punctuation (1)__________4. Citations & References (APA Style) – Did you remember to put quotation marks around direct quotes? Remember to cite paraphrased passages also. (4)__________5. Organization (i.e., Are all sections included and in the appropriate order: Body of Paper with Introduction and Conclusion, Reference Page, Appendix Page, Appendix Contents?) (8)__________6. Are the major points (i.e., the questions in the paper instructions) addressed? (4)__________7. Are terms and concepts explained clearly? Could a college student not familiar with Child Development understand the terms used in your paper? (6)__________8. Are the data described adequately? (3)__________9. Is your writing clear and concise? Are the main points easy to identify? (1)__________10. Does the text flow (e.g., are there good transitions between paragraph)? Sources: • http://www.umuc.edu/ugp/ewp/questions.h tml • http://712educators.about.com/od/grading systems/tp/essaygradetips.htm • http://writing.umn.edu/tww/responding_gra ding/creating_rubrics.htm