Document

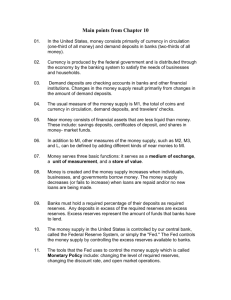

advertisement

Econ 122: Fall 2010 Determination of interest rates: Supply and demand for money and other assets 1 Information items • We will have special TF Friday presentations on finance, math, and financial reform later in course. • Problem 1 will be posted today. • Readings on money are chapter 19 not 18. • Sections this week. If you are Wed pm, go to Thurs pm or other. • Sections: Wed 4-4:50 is in WLH 112 Wed 5-5:50 is in WLH 209 Thurs 4-4:50 is in WLH 203 Thurs 5-5:50 is in WLH 002 Thurs 7-7:50 is in WLH 112 Thurs 8-8:50 is in WLH 007 • Notes on readings [on the board] 2 Federal Reserve Districts 3 3. FOMC Minutes August 10, 2010 The information reviewed at the August 10 meeting indicated that the pace of the economic recovery slowed in recent months …. The economy was operating farther below its potential than they had thought and the pace of recovery had slowed in recent months… Many said they expected underlying inflation to stay below levels they judged most consistent with the dual mandate to promote maximum employment and price stability. Participants viewed the risk of deflation as quite small, but a number judged that the risk of further disinflation had increased somewhat despite the stability of longer-run inflation expectations. The Committee determined it would be appropriate to maintain the target range of 0 to 1/4 percent for the federal funds rate…. [It] Reiterated the expectation that economic conditions were likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period. [Additionally and unconventionally, the Fed will] maintain the total face value of domestic securities held in the System Open Market Account at approximately $2 trillion by reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in longer-term Treasury securities. Voting: 10 to 1 in favor. 4 Administration (cont.) 4. Actual mechanism: • • • • • Open market operations are arranged by the Domestic Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (“the Desk”) Every morning, staff decided if an OMO is needed to keep rate near target. Fed contacts the “primary dealers” (e.g., Goldman Sachs, BNP Paribas, Morgan Stanley, etc.) and asks them to make offers Fed generally makes temporary purchases (“repos” = purchase and forward sale, or the reverse) at 10:30 each day, but generally does not enter more than once per day. Because the Fed intervenes only daily, the FF rate can deviate from the target. 5. Then supply and demand for reserves take over 5 Recent history of Fed Funds rate: 2007-2010 6 Recent history of Fed Funds rate: 2008 7 General equilibrium of assets Have multiple assets of interest rates or yields General theory: - short term nominal rates determined by Fed - long term safe rates determined by expected future short rates. - risky rates = safe rates + risk premium - real interest rate = nominal interest rate - inflation 8 Note on theory of the term structure Many businesses and households borrow risky long-term (mortgages, bonds, etc.). These differ from the federal funds rate in two respects: - term structure (discuss now) - risk premium (postpone) The elementary theory of the term structure is the “expectations theory.” It says that long rates are determined by expected future short rates. Two period example (where rt,T is rate from period t to T): (*) (1+r0,2)2 = (1+r0,1) [1+E(r1,2)] With risk neutrality and other conditions, (*) determines term structure. (Finance people find many deviations, but good first approximation.) 9 Recent term structure interest rates (Treasury) 4.5 Yield to maturity (% per year) 4 Expectations theory says that short rates are expected to rise in coming years. 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 9/18/2009 1 9/17/2008 0.5 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Note that this can explain why Fed makes statement about future rates (look back at Fed statement.) Term or maturity of bond 10 Yield to maturity (% per year) Older term structure interest rates (Treasury) 20 9/18/2009 9/17/2008 18 9/19/2006 May-81 In period of very tight money (198182) short rates were very high, and people expected them to fall. 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Term or maturity of bond 11 Example Short rates: 1 year T-bond = 0.41 % per year 2 year T-bond = 1.03 % per year Implicit expected future rate from 1 to 2 is: (1+r0,2)2 = (1+r0,1) [1+E(r1,2)] (1+.0103)2 = (1+ .0041) [1+E(r1,2)] This implies: E(r1,2) = 1.65 % per year [Again, finance specialists point to deviations from this simple theory.] 12 But the major story to remember is the following: 12 Federal funds rate 3 month T bill 10 year T bond Baa bond rate 10 8 6 4 2 0 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 13 The demand for money 14 Mechanics of OMO: The Fed buys a security… Fed Commercial banks and primary dealers Assets Bonds Liabilities 1000 Bank borrowings 0 Cu Assets 900 Reserves (bank deposits) 100 Liabilities Reserves (bank deposits) 100 Investments 1000 Checkable deposits Equity 1000 100 15 … and this increases reserves … Fed Commercial banks and primary dealers Assets Bonds Liabilities 1000 +10 Bank borrowings 0 Cu Assets 900 Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Liabilities Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Investments Checkable deposits 1000 -10 Equity 1000 100 1. Fed buys bond. 2. Dealer deposits funds in bank. 3. This creates a credit in the account of the bank at the Fed and voilà! the Fed has created reserves. (red) 16 … and normally this increases investments and M Fed Commercial banks and primary dealers Assets Bonds Liabilities 1000 +10 Bank borrowings 0 Cu Assets 900 Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Liabilities Checkable deposits Investments 1000 +100 -10 1. Fed buys bond. 2. Dealer deposits funds in bank. 3. This creates a credit in the account of the bank at the Fed and voilà! the Fed has created reserves. (red) 4. In normal times, the bank lends out the excess, and this leads to money creation (blue). Today, this just increases reserves. Equity 1000 +100 100 17 Actual and required reserves 1,400 1,200 Reserves Required reserves 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 18 … but today it just increases excess reserves Fed Commercial banks and primary dealers Assets Bonds Liabilities 1000 +10 Bank borrowings 0 Cu Assets 900 Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Liabilities Reserves (bank deposits) 100 +10 Investments 1000 -10 Checkable deposits Equity 1000 100 1. Fed buys assess backed mortgage (from bank for simplicity) 2. Bank is glad to unload it, and just holds excess reserves. 3. No impact on the money supply or on federal funds rate. A (very small) impact on mortgage interest rates. 19 Now let’s move on to money demand Recall that monetary policy operates on the market for reserves. The demand for reserves is a derived demand – derived from the demand for money. We need therefore to understand the foundations of the demand for money, and particularly why it depends upon the interest rate. 20 Balance Sheet of Household Assets Cu D Bh (net) E Cu = currency Bh = household bonds (net of Liabilities NW = household net worth E = equity NW =HH net worth debts and mortgages) D = checkable deposits 21 Real Wealth of US Households Balance sheet of households Total assets 2,007 2,009 Change 29,577 24,847 -4,730 Tangible assets 24,851 20,026 -4,825 Real estate 22,305 18,272 -4,033 7,284 7,760 476 7,284 7,760 476 212 300 88 3,834 4,327 493 10,532 6,266 -4,266 5,017 3,741 -1,276 13,865 10,656 -3,208 1,371 1,379 8 Financial assets Deposits and currency Checkable deposits and currency Credit market instruments (ex. equities) Corporate equities Mutual fund share holdings Pension fund reserves Proprietors' equity Misc … Total financial liabilities 14,379 14,068 -311 Home mortgages 10,585 10,402 -183 Consumer credit 2,517 2,476 -41 53,140 -14,505 Misc. Net worth (market value) … 67,645 Source: Federal Reserve, Flow of Funds, Table B.100; in 2009 $. 22 Simplification for macro • Let k = number of “independent assets.” In macro, we generally use k = 2 (money and bonds). • Further assume no inflation, so inflation = п =0 and r = i. • Assume that nominal interest rate on money = 0. • We then substitute in the wealth identity to get: 1 M (t )/ P (t ) D [0, r (t ), W (t ) / P (t ) , Y (t )] W (t ) B (t ) M (t ) • In short run, W(t) is fixed, so this reduces to the demand for money equation: M (t )/ P (t ) D [r (t ), Y(t ) ] D[ i (t ), Y (t )] • This is the canonical equation used in macroeconomics. 23 Fisher Theory of Transactions Demand for Money • The transactions demand is a specific case of an inventory demand theory (think shoe store) • Used in advanced macro in “cash-in-advance models” • Simple example: earn Y at beginning (example is per year; more generally would be per payment period of say month) spend evenly at rate of Y per period constant price level money has yield of 0 no opportunity to move from money to other assets. In this case, we see that the average money holdings: M* = Y/2 This leads to “monetarist” theory of M. Friedman; money demand insensitive to interest rates and “only money matters.” 24 Y Average money balance M = Y/2 0 1 25 What’s wrong with this theory? 26 Opportunity cost of money balances 7 Interest rates (percent per year) 3-month Treasury bills 6 5 4 Implicit cost of holding money 3 2 1 0 Interest rate on money (M1) 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 Source: Treasury interest rate from Federal Reserve; interest rate on checking accounts 27 from Informa Research Services, Inc. More general demand for money What happens if we have other assets? • If have bonds as well as money, then can move some of money to bonds to earn interest. • Yale train to New York in 1950s; “repos” today for wholesale • This leads to more general theories in which the demand for money is interest-elastic Baumol-Tobin model. • This is an explicit model of how income, interest rates, and other factors determine how often we move money to bonds. • Typical methodology of macroeconomics. • We will cover briefly and do more carefully in section (see Mankiw, pp. 559-562) 28 Baumol-Tobin model Problem with Fisher model: Assumes only one asset (M) Must recognize that there are other assets that you can purchase depending upon costs and benefits Say that can move back and forth into and out of bonds (M and B) Bonds yield iB > iM = 0. Go to bank at beginning of period and deposit half in bonds; then go in mid-period to move to money so that you can buy your pizzas. For one trip, have only half the money and the other half is earning interest. 29 Y Average money balances are triangles labeled “Money” Money For 2 trips to the bank, have M* = Y/4 For N trips to the bank, have M* = Y/2N Bonds Money 0 1 30 Money and finance: The finale Irving Fisher, Yale (1867-1947) Milton Friedman, Chicago (1912-2006) James Tobin, Yale (1918-2002) 31 Daily life in macroeconomics 32 Info items Federico will do a special session on finance this Friday, here at 11:35. Reading is from a free online textbook on Corporate Finance, available at the course website. 33 Optimizing money balances (special case of optimal inventory): Total cost = C(N) = Forgone Interest + Cost of trips = iY/(2N) + FN Maximizing to determine optimal number of trips (N*): dC/dN = 0 = - iY/(2N*2) + F N* = (iY/2F)½ Optimal average money holding are M* = Y/(2N*) = (YF/2i)½ This is the famous “square root inventory rule” for money holdings What are elasticities of M w.r.t. Y and i (EM,Y and EM,i )? [E =½ ] This is the crux of the debate between monetarists and Keynesians: • Is the interest elasticity EM,i = 0 or < 0? • If = 0, monetarist; if < 0 then Keynesian • Huge debate in 1960s and 1970s; pretty much settled now. 34 Empirical test of money demand equation: Is money demand interest elastic (1975-2009)? 16 Short term interest rate 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 800 1,000 1,200 1,400 1,600 1,800 Real money demand 35 Econometric estimate of money demand equation Dependent Variable: ln(Real M1) Method: Least Squares Sample (adjusted): 1959Q2 2009Q2 Coefficient ln(3 mo Tbill) ln(real GDP) Constant, AR1, … -0.040 0.34 t-Statistic Prob. -7.0 3.2 0.0000 0.0016 Standard error regression = 0.033 ****************************************************************************************** Elasticities have correct sign and are statistically significant but interest rate coefficient is small. • Why is EM,i so small? Wrong model? Behavioral economics? Corner solution? 36 i Short term interest rate DM SM S’M i* i*’ DM Money balances M* M*’ 37 Monetary policy helpless: the liquidity trap • In depressions or deep recessions, when i close to zero, have highly elastic demand for money and reserves – US 1930s, Japan 1990s and 2000s, US 2010! • Monetary policy therefore ineffective (note what happens when M supply shifts from S to S’’’ in figure on next page). • The Fed has “run out of bullets,” or at least conventional bullets, and must turn to “unconventional instruments” • This is the nightmare of central banks! 38 The supply and demand for bank reserves, 1950-2010 S 9 S’’ 8 S’’’ Federal funds rate 7 6 S’ 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 400 800 Bank reserves 1,200 39 Portfolio Theories More general theories • This goes back to our general equilibrium model above; multiple assets (money, bonds, stocks, foreign assets,...) • Portfolio theory considers how to allocate wealth among assets • Yale’s management of endowment • Individual’s management of 401(k) account Standard analysis examines • preferences (like life-cycle model + preference toward risk) • asset risks and returns • Many good courses at Yale and B. Schools This leads to the modern theory of finance. • You can get a preview on Friday from Federico (same time, same station; free reading online) 40