A Research on plagiarism

advertisement

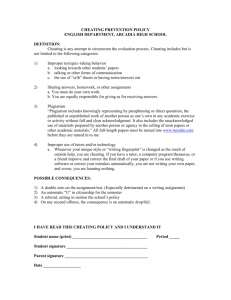

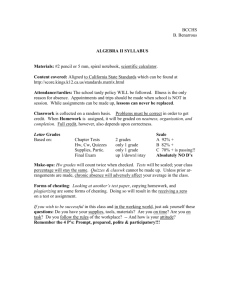

Cheating and Plagiarism: Perceptions and Practice of 1st Year IT Students Judy Sheard, Martin Dick School of Computer Science and Software Engineering Monash University Melbourne 3145, Australia judy.sheard@csse.monash.edu.au martin.dick@csse.monash.edu.au selby.markham@csse.monash.edu.au Abstract A study of cheating and plagiarism using a unique, scenario based format, has provided an insight into attitudes towards questionable work practices of first year information technology students’ within the School of Computer Science and Software Engineering (CSSE) of Monash University, and the School of Information Technology (IT) of Swinburne University. Students at both institutions showed similar responses to a range of cheating behaviours, in line with other literature. Plagiarism and cheating are widely tolerated and commonly practised, at least on the lower end of the spectrum of seriousness. However there were some areas of significant difference between the two student samples that warrant further research to develop strategic approaches for limiting cheating practices. 1 Introduction There have been many reports, both informal and from research studies, of the high incidence of cheating and plagiarism among tertiary students. The general perception is that this problem is endemic in universities worldwide and some believe it is increasing [12]. Anecdotal and reported evidence indicate there are many ways which students cheat, and the now widespread use of the Internet in universities offers yet another resource for students inclined to this type of behaviour [15]. Although there is no doubt that cheating and plagiarism exist in Australian universities, the extent Ian Macdonald, Meagan Walsh School of Information Technology Swinburne University Melbourne 3122, Australia imacdonald@swin.edu.au mwalsh@swin.edu.au of the problem is difficult to establish. Within the School of Computer Science and Software Engineering of Monash University and the School of Information Technology of Swinburne University, teaching staff have raised concerns about the incidence of cheating and plagiarism amongst information technology (IT) students. Both universities, in recent years, have introduced measures to heighten student awareness of the seriousness of cheating and plagiarism, and inform students of the university regulations on academic misconduct. However the problems appear to continue. To determine the extent of the problem and inform the development of measures which may be taken to discourage the practice of cheating and plagiarism, a combined study of computing students at both institutions was conducted. This has enabled a comparison of the two student groups to help determine if questionable practices were particular to their institution, or similar to that experienced elsewhere. The study was conducted using a survey of computing students at both institutions. The survey aimed to establish what practices computing students perceive to be cheating, the extent of questionable behaviour, and reasons that encourage or inhibit cheating. The scenario based questionnaire used in the student is unique against what has been found in the literature in this area. This study is part of a wider project investigating questionable practices. The longer term aim of this project is to determine measures which may be taken to discourage the practice of cheating and plagiarism. 2 The Extent of the Problem There is a wealth of literature on cheating and plagiarism within tertiary institutions. Although most of the research into these practices has been carried out in the USA, there are many informal reports and sufficient anecdotal evidence to suggest that this problem is worldwide. A recent international study by Olasehinde supports the view that this is a global problem [11]. In Australia, recent press reports have highlighted this issue as one of major concern within tertiary institutions [8,11,15]. Many studies have investigated the extent of undergraduate student cheating, and although the results of these vary, the self-admission of cheating in most cases is alarmingly high [4,14]. Significantly, some of the highest levels of cheating have been found in the most recent studies. In a survey of 500 college students by Graham, Monday and O’Brien, 90% admitted to cheating at least once [5]; a survey of 422 students by Roberts, Anderson and Yanish found that 91.7% of the students claimed to have engaged in at least 1 of 27 items of academic misconduct [10]. In a United Kingdom study of 943 students by Newstead, Franklyn-Stokes and Armstead, 88% of students admitted to engaging in at least one type of cheating behaviour [9]. In each of these studies, many students who admitted to cheating also claimed to have cheated on more than one occasion. When comparing studies of the extent of cheating practices it is important to understand what students consider constitutes cheating behaviour. Some studies have done this by asking students to classify behaviours as a dichotomous rating [1,14]. However, the Newstead study allowed more discernment of the degree acceptability of various practices by asking students to rate on a six point scale the seriousness of 22 cheating behaviours [9]. As might be expected, research studies indicate that the frequency of practice between particular cheating behaviours varies greatly. Furthermore, a negative relationship exists between cheating practices which students claim occur frequently, and those practices that a large percentage of students define as cheating [1]. For example, a widely practised form of cheating involves paraphrasing material from another source without acknowledgement, and this was generally rated as a mild form of cheating by students. Similarly the most serious forms of cheating involved cheating in examinations, and these were the least reported as practised or perceived as happening by students [9]. Estimates of the actual extent of cheating in these studies have relied mostly on the self-reporting of students, however, there is some doubt as to the reliability of these figures. Scheers and Dayton (cited in Brown) estimated that between 39% and 83% of respondents to self-admission surveys under-reported, indicating that the actual extent of cheating is higher than reported [2]. Exam cheating is reported by students as one of the least occurring forms of cheating however an experiment with 78 college students exposed to opportunities to cheat found that 59% cheated in at least one exam, and most cheated in more than one exam [7]. Perhaps more indication of the prevalence of cheating may be gained from students’ perceptions of cheating practice among their friends and classmates. In surveys, students generally indicate more awareness of other’s cheating than admissions of personal practice [9]. However, they also indicate a reluctance to report on fellow students whom they observe cheating. A study of 791 undergraduate student found that 90% said they would not report a cheating incident [13]. A more recent study found that 49% to 86% reported that they would not be likely to report cheating of another student [3]. Another worrying indication of the extent of the problem was a study of 380 undergraduate students which found that although 54.1% admitted to cheating only 1.3% reported that they had ever been caught cheating [6] 3 Research Method 3.1 Participants Students from selected undergraduate subjects in the first year of undergraduate IT courses at Monash and Swinburne Universities were invited to participate in the study. Monash and Swinburne are metropolitan universities in a large Australian city. The courses have similar entry standards and draw on a similar student population. 3.2 Survey To determine students’ views of what constitutes cheating and plagiarism, and their own and other’s inclination to cheating practices, a survey questionnaire was developed by staff at Monash University. The survey was trialed and approved by the Monash and Swinburne Research Ethics Committees. The questionnaire contained questions to determine demographic information, students’ rating of the acceptability of various cheating practices described in 18 different scenarios, students’ practice and knowledge of others practising each cheating practice, and reasons which could cause cheating or could prevent cheating. The questionnaire was titled “Questionable Work Practices” and can be found at: http://cerg.csse.monash.edu.au/ 3.3 Procedure The students were surveyed near the end of second semester 2000 at Monash University and towards the end of first semester 2001 at Swinburne University. A paper questionnaire was given to the students in their tutorial classes. Most students returned a completed questionnaire. 4 Survey Results and Discussion 4.1 Demographic Profile A total of 287 valid questionnaires were returned from full-time students (137 Monash and 150 Swinburne). The demographic profile of the two groups was similar. The Monash students were 67.2% male compared with 78.0% of the Swinburne group. There were 33.1% overseas students in the Monash group compared with 28.7% in the Swinburne group. However, Chi-square tests on cross tabulations of these classifications produced no significant differences. 4.2 Acceptability of cheating practices The students were asked to rate the acceptability of various questionable work practices described in 18 different scenarios. The scenarios are briefly described in Table 1. For each scenario respondents were asked to rate how acceptable the practice was, using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates acceptable and 5 indicates not acceptable. Independent groups t-tests were used to determine differences in the means obtained for the students’ ratings of the acceptability of scenarios when classified according to university. Tests were not performed on scenarios where the distributions of responses showed high skewness or kurtosis. The acceptability ratings showed that both groups of students found scenarios 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 unacceptable or highly unacceptable (M > 3.5). These were scenarios involving exam cheating, theft, fraud and gross plagiarism. The Monash students rated every cheating practice, except one, as more acceptable however the differences were only significant in three scenarios as follows. Two students collaborating on an assignment meant to be completed individually (t(280)= –2.15, p<0.05). Posting to an Internet newsgroup for individually (t(279)= –2.80, p<0.05). (This scenario is not considered to be a cheating practice by the authors) Submitting a friend’s assignment from a past running of the subject individually (t(284)= –3.51, p<0.05). First year programming students at Monash and Swinburne are encouraged to help each other with their work, however at Monash students are assessed by interview for their assignment work. A strong emphasis is placed on their ability to explain their work rather than acknowledging where it originated. At Swinburne assignments are regularly submitted electronically to a system that automatically checks for plagiarism. Here the emphasis is on unique code, rather than a personal defense of understanding. This may have had an influence on their rating of scenarios 1 and 5. Factors affecting the decision making of students are an area of further research. 4.3 Admissions of cheating and knowledge of others’ cheating For each of the 18 scenarios, the students were asked if they had practised it personally or knew someone who had practised it. Cross tabulations were performed to determine differences between numbers of Monash and Swinburne students admitting to practising each scenario, or knowing someone personally who had practised the scenario. The results are shown in Table 1. The non responses for these questions were never greater than 3%. The frequency of students’ cheating practice was determined by totalling the number of scenarios practised. Scenarios 2 and 3, which are not considered cheating practices, were not included in these totals. Significantly more Monash students (85.4%) admitted to cheating than Swinburne students (69.3%). The maximum number of scenarios practised by any students was 15 and there were no students who admitted to practising every scenario. As might be expected from their higher level of acceptance of cheating behaviours, Monash students admitted to more cheating practices than the Swinburne students. A factor in these discrepancies may be that at the time of the survey Monash students had been at university for an extra semester, and this warrants further investigation. Monash students were significantly more likely to engage in practices which involved colluding with a friend or fellow student and submitting work which was not their own. It is interesting to note that these practices were rated as unacceptable by both groups of students. The Monash students also perceived the extent of cheating at their university to be higher for every practice and significantly higher for six practices. These all involved cheating on assignment work or assessable lab exercises. 4.4 Detection of cheating Most students in both groups (76.9% Monash and 81.5% Swinburne) indicated that they would do nothing if they observed a student cheating in an exam. Similar percentages indicated that they would do nothing if they observed someone cheating in an assignment (77.4% Monash and 78.5% Swinburne). Why this should be tolerated so broadly is another area for future research. One hypothesis is that there are no effective actions available to students who become aware of cheating. 5 Student perceptions of staff University attitudes to cheating and There was agreement in the students’ perceptions of how strongly lecturers and tutors felt about preventing cheating in their subjects, with students at both universities believing that their teachers felt strongly about the problem. Most students claimed they were aware of cheating and plagiarism regulations at their university, however the Swinburne students more strongly believed that their university was committed to reducing cheating than the Monash students (t (277)= -2.04, p<0.05). This is probably a consequence of a recent crackdown on plagiarism at Swinburne School of IT, which has involved students receiving regular reminders of policy and penalties in their lectures from senior staff. At Monash the IT Faculty has developed a policy on cheating and plagiarism which lecturers are encouraged to publish on their subject websites. Students are made aware of this in subject handbooks and assignment specifications, but this may not have the impact of the direct confrontation practised at Swinburne. [5] Graham, A.M., Monday, J., O'Brien, K. and Steffen, S., Cheating at small colleges: an examination of student and faculty attitudes and behaviours, Journal of College Student Develpment, 35 (1994) 255-260. The survey of first year undergraduate IT students across two universities has provided an opportunity to compare the students’ perceptions of cheating and plagiarism and their perceptions of cheating behaviour. Results were broadly in agreement with other studies, suggesting that, at least on the lower end of the seriousness spectrum, cheating practices are commonplace and widely tolerated despite awareness of university policy. Inappropriate styles of collaboration such as swapping assignments with a friend are particularly evident. [6] Haines, V.J., Diekhoff, G.M., LaBeff, E.E. and Clark, R.E., College cheating: Immaturity, lack of commitment, and the neutralising attitude, Research in Higher education, 25 (1986) 342-354. [7] Hetherington, E.M. and Feldman, S.E., College cheating as a function of subject and situational variables, Journal of Educational Psychology, 55 (1964) 212-218. There was strong agreement among all students about the unacceptability of the most serious forms of cheating. Most students rated exam cheating, or behaviours involving fraud or theft as not acceptable. In line with findings from other studies, these scenarios were also practised by the lowest numbers of students at both universities. [8] Murphy, P., How the Internet is invading the halls: Cheats.com., The Age, 2000. [9] Newstead, S.E., Franklyn-Stokes, A. and Armstead, P., Individual differences in student cheating, Journal of Educational Psychology, 88 (1996) 229-241. [10] Roberts, P., Anderson, J. and Yanish, P., Academic misconduct: where do we start?, Northern Rocky Research Association, Jackson, Wyoming, 1997. [11] Saltau, C., Fear of failure drives student exam cheats., The Age, Melbourne, 2000, pp. 8. [12] Schemo, D.J., Degree of dishonour., The Age, melbourne, 2001, pp. 16. 6 Conclusion There were also significant variations in cheating practices between the universities. Follow up studies will explore reasons for the variations, possibly leading to the development of measures that can be taken to address this problem. 7 [1] References Barnett, D.C. and Dalton, J.C., Why college students cheat?, Journal of College Student Personnel, 22 (1981) 545-551. [2] Brown, B., The academic ethics of graduate business students: a survey, Journal of education for Business, 70 (1995) 151-156. [13] [3] Cole, S. and McCabe, D.L., Issues in academic integrity., New Directions for Student Services, Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1996, pp. 67-77. Stafford, T.H., Jr, Academic dishonesty at North Carolina State University: a studentfaculty response., North Carolina State University, Raleigh, 1976, pp. 22 pages. [14] Davis, S.F. and Ludvigson, H.W., Faculty Forum: Additional data on academic dishonesty and a proposal for remediation, Teaching of Psychology, 22 (1995) 119-121. Stern, E.B. and Havlicek, L., Academic misconduct: results of faculty and undergraduate student surveys, Journal of Allied Health, 5 (1986) 129-142. [15] Szego, J., Top mark: is it hard work or a dotcon?, The Age, Melbourne, 2000, pp. 15. [4] Table 1 Students’ admissions of cheating practice and perception of other students’ cheating practice Practised personally Scenario Mon % Swin % 1. Two students collaborating on an assignment meant to be completed individually 51.5 42.4 2. Posting to an Internet newsgroup for assistance 20.9 10.2 3. Showing assignment work to a lecturer for guidance 28.1 4. Resubmitting an assignment from a previous subject in a new subject Mon % Swin % 74.6 63.2 44.0 15.0 25.2 41.2 37.7 42.1 45.9 40.7 32.9 5. Submitting a friend’s assignment from a past running of the subject 21.3 17.4 36.0 24.8 6. Being given the answer to a tutorial exercise worth 5% by a class mate if the computer you used has problems 11.0 3.3 36.0 17.3 12.89(1) * 7. Hiring a person to write your assignment for you 4.4 0.7 15.6 3.4 12.67(1) * 8. Copying another student’s assignment from their computer without their knowledge and submitting it 10.4 5.4 28.1 13.3 9.62(1)* 9. Not informing the tutor that an assignment has been given too high a mark 27.8 24.2 35.1 28.9 10. Taking a student’s assignment from a lecturer’s pigeonhole and copying it 3.0 2.0 3.7 4.0 11. Copying material for an essay from the Internet 22.4 18.8 35.8 26.2 12. Copying the majority of an assignment from a friend’s assignment, but doing a fair bit of work yourself 33.6 28.2 53.0 37.6 6.77(1)* 13. Copying all of an assignment given to you by a friend 10.4 2.7 32.8 18.1 8.13(1)* 14. Hiring someone to sit an exam for you 2.2 2.0 4.5 4.7 15. Using a hidden sheet of paper with important facts during an exam 2.2 2.7 14.2 22.8 16. Obtaining a medical certificate from a doctor to get an extension when you are not sick 11.9 6.7 33.3 32.9 17. Copying material for an essay from a text book 23.7 18.4 35.6 31.3 18. Swapping assignments with a friend, so that each does one assignment, instead of doing both 8.1 9.5 20.7 19.0 * = p < 0.05 X Know someone personally 6.18(1)* 6.50(1)* 7.05(1)* X 28.86(1) *