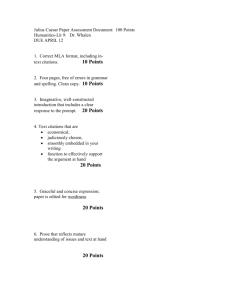

JuliusCaesarBackgroundHandouts

advertisement

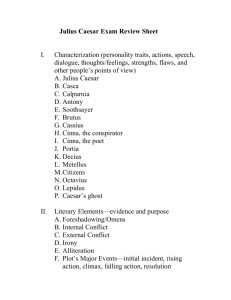

Julius Caesar Background: For centuries, Romans debated and even fought civil wars while trying to decide whether a monarchy, a republic or a dictatorship was the best form of government. Until 509 B.C., Rome was a monarchy, but, in that year, the Brutus family evicted Trarquinius Superbus from the throne and Rome was established as a republic. By 100 B.C., Rome was a moderate democracy in form; in actual practice, the Senate was ruling Rome. In 60 B.C., a triumvirate (a 3-man rule) of Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey was formed to govern Rome. In 58 B.C., Caesar was made governor of part of Gaul, and at the age of 44 began his military career. During the next ten years, he proceeded to conquer all of Gaul. After Crassus was killed in battle, trouble began to develop between Pompey and Caesar. Pompey, jealous of Caesar’s popularity, persuaded the Senate to order Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome. But Caesar invaded Rome and made himself absolute ruler of Rome. Meanwhile, Pompey fled to Greece. Caesar defeated Pompey’s army and Pompey fled to Egypt where he was later murdered. Three years after Caesar defeated Pompey’s army, Caesar defeated Pompey’s two sons. By now, Caesar had been made dictator for life. Thus, as Shakespeare begins his play with Caesar returning in victory from Spain, Caesar was the undisputed leader of master of the entire Roman world. Hero: Just as Romeo and Juliet was a tragedy, so is Julius Caesar. Unlike Romeo and Juliet where the title characters were the heroes of the play, Julius Caesar is not the hero. The hero in this play is Brutus, a noble man who truly believes his actions are for the good of his country. Brutus dominates much of the play. Perhaps the title should be The Tragedy of Marcus Brutus. Setting: The setting is Rome, Italy, part of the continent of Europe, and it is situated along the Tiber River. Life in Rome: There were two classes of people in Rome. The people were either rich or poor. The rich were called Patricians and the poor were called Plebeians. Politics: Julius Caesar is a political play, and political issues are the root of the tragic conflict in the play. It is a play about a general who would be king, but who, because of his own pride and ambition, meets an untimely death. Shakespeare raises the questions of whether good government must be based on morality. In this respect the play has relevance to the politics of the modern world. Timeline: Shakespeare compresses the actual historical time of 3 years into a period of 6 days. Big Question on Political Assassination: is it ever right to use force to remove a ruler from power? MONARCHY in Elizabethan Times o Elizabeth I, ruled with an iron hand for forty-five years (from 1558 to 1603), yet her subjects had great affection for her. The arts flourished and the economy prospered. Relatively peaceful period - Elizabeth's reign-and the reign of other Tudor monarchs, beginning with Henry VII in 1485--brought an end to the anarchy that had been England's fate during the Wars of the Roses (1455-84). Conclusion: only a strong, benevolent ruler could protect the peace and save the country from plunging into chaos again. ORDER in Elizabethan Times Julius Caesar first performed in 1599, Elizabeth was old with no successors (Elizabeth never married, no heirs); fear that someone would try to grab power and plunge the country into civil war. Elizabethans strong sense of order - universe was ruled by a benevolent God, and everything had a divine purpose - The king's right to rule came from God himself (divine right of kings), and opposition to the king earned the wrath of God and threw the whole system into disorder. Everyone was linked together by a chain of rights and obligations, and when someone broke that chain, the whole system broke down and plunged the world into chaos (Great Chain of Being). Julius Caesar begins with a human act that, like a virus, infects the body of the Roman state. No one is untouched; some grow sick, some die. But in time the poison works its way out of the system and the state grows healthy again… or does it? In Shakespeare's world, health, not sickness, is the natural condition of man in God's divine plan. THE IMPORTANCE OF FRIENDSHIP & LOYALTY Friendship is at the center of Shakespeare's vision of an ordered, harmonious world. Disloyalty and distrust cause this world to crumble. Relationships suffer when people put their principles ahead of their affections, and when they let their roles as public officials interfere with their private lives. As death approaches, characters forget their worldly ambitions, and speak about the loyalty of friends. THE POWER OF LANGUAGE TO PERSUADE AND DISTORT OR CONCEAL TRUTH In Julius Caesar people use language to disguise their thoughts and feelings, and to distort the truth. Language is used to humiliate and flatter. Words are powerful weapons that turn evil into good and throw an entire country into civil war. THE HIDDEN PRIVATE LIVES OF PUBLIC FIGURES Shakespeare reminds us that behind their masks of fame are mortals like the rest of us-with the same prejudices, physical handicaps, hopes, and fears. When these public figures try to live up to their own self-images, they bring destruction on themselves, and on the world. FREE WILL, FATE AND THE SUPERNATURAL A sense of fate hangs over the events in Julius Caesar-a sense that the assassination is inevitable and that the fortunes of the characters have been determined in advance. The characters are foolish to ignore prophecies and omens, which invariably come true; yet they are free to act as though the future were unknown. They are the playthings of powers they can neither understand nor control, yet they are held accountable for everything they do. PRAGMATISTS AND MEN OF PRINCIPLE Shakespeare is comparing two types of people: o the man of fixed moral standards, who expects others to be as honorable as himself; o and the pragmatist, who accepts the world for what it is and does everything necessary to achieve his goals. The pragmatist is less admirable, but more effective. Shakespeare is either o (a) pointing out the uselessness of morals and principles in a corrupt world, or o (b) dramatizing the tragedy of a noble man destroyed by a world less perfect than he is. THE ASSASSINATION The Murder Is Just o A ruler forfeits his right to rule when he oversteps the heavenappointed limits to his power. o Caesar deserves to die on two counts: first, he considers himself an equal to the gods; and second, he threatens to undermine hundreds of years of republican (representative) rule. o Brutus sacrifices his life to preserve the freedom of the people, and to save his country from the clutches of a tyrant. The Murder Is Unjust o Shakespeare's contemporaries respected strong rulers, who could check the dangerous impulses of the masses and protect their country from civil war. They believed that order and stability were worth preserving at any price. o Shakespeare's play may therefore be a warning against the use of violence to overthrow authority. o The assassination destroys nothing but the conspirators themselves, since Caesar's spirit lives on in the hearts of the people. When’s When in Julius Caesar The chart below gives the actual historical time frame as well as the dramatic time frame used by Shakespeare in his play. Day Day 1 In Shakespeare Six Days with Intervals In History Date Three Years Act 1 Scenes 1 and 2. – Caesar’s Triumph and the Lupercalia being placed on the same day. Interval Oct. 45 B. C. – 44 B.C. Caesar’s triumph for his victory at Munda, Spain. Feb. 15 Day 2 Act 1 Scene 2 – nighttime March 14 Day 3 Acts 2 and 3 March 15 Festival of the Lupercalia Interval of 1 month during which Caesar prepares for an expedition into Illyricum and Parthia Assassination of Caesar. 43 B.C. Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Interval of more than 7 months. Brutus is in Macedonia and Cassius is in Syria. A 3-day conference of the Triumvirate at Bononia Interval October 43 B.C. Act 4 Scene 1 Interval 42 B.C. Interval of about 3 months. Cicero and others are put to death. January Interval of about 9 months Battle of Philippi – The second engagement, 20 days after the first. Act 4 Scenes 2 and 3 Interval Act 5. The two engagements at Phillipi being described as one. October Who’s Who in Julius Caesar The First Triumvirate The Second Triumvirate (before the play begins) Julius Caesar Crassus Pompey (after Caesar dies) Octavious Caesar Marc Antony M. Lepidus Julius Caesar - dictator of Rome Calpurnia – wife of Caesar Marcus Brutus – Roman who is the hero of the play Portia – Brutus’ wife Servants to Brutus Comrades in Arms with Brutus Conspirators against Caesar Claudis Clitus Dardanius Lucius Strato Varro Young Cato Messala Titinius Volumnius Lucilius Marcus Brutus Decius Brutus Casca Cassius Mettelus Cimber Cinna Ligarius Trebonius Pindarus – servant of Cassius Artemidorus – a fortuneteller Senators – Cicero, Popilius Lena, and Publius Tribunes – Flavius and Marullus The Roman Republican Constitution Introduction The Romans never had a written constitution, but their form of their government, especially from the time of the passage of the lex Hortensia (287 B.C.), roughly parallels the modern American division of executive, legislative, and judical branches, although the senate doesn't neatly fit any of these categories. What follows is a fairly traditional, Mommsenian reconstruction, though at this level of detail most of the facts (if not the significance of, e.g., the patrician/plebian distinction) are not too controversial. One should be aware, however, of the difficulties surrounding the understanding of forms of government (as well as most other issues) during the first two centuries of the Republic. EXECUTIVE BRANCH -- the elected magistrates Collegiality: With the exception of the dictatorship, all offices were collegial, that is, held by at least two men. All members of a college were of equal rank and could veto acts of other members; higher magistrates could veto acts of lower magistrates. The name of each office listed below is followed (in parentheses) by the number of office-holders; note that in several cases the number changes over time (normally increasing). Annual tenure: With the exception of the dictatorship (6 months) and the censorship (18 months), the term of office was limited to one year. The rules for holding office for multiple or sucessive terms were a matter of considerable contention over time. CONSULS (2): chief civil and military magistrates; invested with imperium (consular imperium was considered maius ("greater") than that of praetors); convened senate and curiate and centuriate assemblies. PRAETORS (2-8): had imperium; main functions (1) military commands (governors) (2) administered civil law at Rome. AEDILES (2): plebian (plebian only) and curule (plebian or patrician); in charge of religious festivals, public games, temples, upkeep of city, regulation of marketplaces, grain supply. QUAESTORS (2-40): financial officers and administrative assistants (civil and military); in charge of state treasury at Rome; in field, served as quartermasters and seconds- in-command. TRIBUNES (2-10): charged with protection of lives and property of plebians; their persons were inviolable (sacrosanct); had power of veto (Lat. "I forbid") over elections, laws, decrees of the senate, and the acts of all other magistrates (except dictator); convened tribal assembly and elicited plebiscites, which after 287 B.C. (lex Hortensia) had force of law. CENSORS (2): elected every 5 years to conduct census, enroll new citizens, review roll of senate; controlled public morals and supervised leasing of public contracts; in protocol ranked below praetors and above aediles, but in practice, the pinnacle of a senatorial career (ex- consuls only) -- enormous prestige and influence (auctoritas). DICTATOR (1): in times of military emergency appointed by consuls; dictator appointed a Master of the Horse to lead cavalry; tenure limited to 6 months or duration of crisis, whichever was shorter; not subject to veto. SENATE -originally an advisory board composed of the heads of patrician families, came to be an assembly of former magistrates (ex-consuls, -praetors, and -questors, though the last appear to have had relatively little influence); the most powerful organ of Republican government and the only body of state that could develop consistent long-term policy. -enacted "decrees of the senate" (senatus consulta), which apparenly had not formal authority, but often in practice decided matters. -took cognizance of virtually all public matters, but most important areas of competence were in foreign policy (including the conduct of war) and financial administration. LEGISLATIVE BRANCH -- the three citizen assemblies (cf. Senate) -all 3 assemblies included the entire electorate, but each had a different internal organization (and therefore differences in the weight of an individual citizen's vote). -all 3 assemblies made up of voting units; the single vote of each voting unit determined by a majority of the voters in that unit; measures passed by a simple majority of the units. -called comitia. specifically the comitia curiata, comitia centuriata, and comitia plebis tributa (also the concilium plebis or comitia populi tributa). CURIATE ASSEMBLY: oldest (early Rome); units of organization: the 30 curiae (sing: curia) of the early city (10 for each of the early, "Romulan" tribes), based on clan and family associations; became obsolete as a legislative body but preserved functions of endowing senior magistrates with imperium and witnessing religious affairs. The head of each curia ages at least 50 and elected for life; assembly effectively controled by patricians, partially through clientela) CENTURIATE ASSEMBLY: most important; units of organization: 193 centuries, based on wealth and age; originally military units with membership based on capability to furnish armed men in groups of 100 (convened outside pomerium); elected censors and magistrates with imperium (consuls and praetors); proper body for declaring war; passed some laws (leges, sing. lex); served as highest court of appeal in cases involving capital punishment. 118 centuries controlled by top 3 of 9 "classes" (minimum property qualifications for third class in first cent. B.C.-HS 75,000); assembly controlled by landed aristocracy. TRIBAL ASSEMBLY: originally for election of tribunes and deliberation of plebeians; units of organization: the urban and 31 rural tribes, based on place of residence until 241 B.C., thereafter local significance largely lost; elected lower magistrates (tribunes, aediles, quaestors); since simpler to convene and register 35 tribes than 193 centuries, more frequently used to pass legislation (plebiscites). Voting in favor of 31 less densely populated rural tribes; presence in Rome require to cast ballot: assembly controlled by landed aristocracy (villa owners). Eventually became chief law-making body. < criminal and civil -- BRANCH>Civil litigation: chief official-Praetor. The praetor did not try cases but presided only in preliminary stages; determined nature of suit and issued a "formula" precisely defining the legal point(s) at issue, then assigned case to be tried before a delegated judge (iudex) or board of arbiters (3-5 recuperatores for minor cases, one of the four panels of "The one hundred men" (centumviri) for causes célèbres (inheritances and financial affairs of the rich)). Judge or arbiters heard case, rendered judgment, and imposed fine. Criminal prosecution: originally major crimes against the state tried before centuriate assembly, but by late Republic (after Sulla) most cases prosecuted before one of the quaestiones perpetuae ("standing jury courts"), each with a specific jurisdiction, e.g., treason (maiestas), electoral corruption (ambitus), extortion in the provinces (repetundae), embezzlement of public funds, murder and poisoning, forgery, violence (vis), etc. Juries were large (c. 50-75 members), composed of senators and (after the tribunate of C. Gracchus in 122) knights, and were empanelled from an annual list of eligible jurors (briefly restricted to the senate again by Sulla). OTHER First plebeian consul in 366 B.C., first plebeian dictator 356, first plebeian censor 351, first plebeian praetor 336. The many priestly colleges (flamines, augures, pontifex maximus, etc.) were also state offices, held mostly by patricians. Imperium is the power of magistrates to command armies and (within limits) to coerce citizens. From: http://www.utexas.edu/depts/classics/documents/RepGov.html Ides of March Marked Murder of Julius Caesar Jennifer Vernon for National Geographic News March 12, 2004 Julius Caesar's bloody assassination on March 15, 44 B.C., forever marked March 15, or the Ides of March, as a day of infamy. It has fascinated scholars and writers ever since. For ancient Romans living before that event, however, an ides was merely one of several common calendar terms (see sidebar) used to mark monthly lunar events. The ides simply marked the appearance of the full moon. But the Ides of March assumed a whole new identity after the events of 44 B.C. The phrase came to represent a specific day of abrupt change that set off a ripple of repercussions throughout Roman society and beyond. Josiah Osgood, an assistant professor of classics at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., said: "You can read in Cicero's letters from the months after the Ides of March. … He even says, 'The Ides changed everything.'" By the time of Caesar, Rome had a long-established republican government headed by two consuls with joint powers. Praetors were one step below consuls in the power chain and handled judicial matters. A body of citizens forming the Senate proposed legislation, which general people's assemblies then approved by vote. A special temporary office, that of dictator, was established for use only during times of extreme civil unrest. The Romans had no love for kings. According to legend, they expelled their last one in 509 B.C. While Caesar had made pointed and public displays of turning down offers of kingship, he showed no reluctance to accept the office of "dictator for life" in February 44 B.C. According to Osgood, this action may have sealed his fate in the minds of his enemies. "We can see [now] that that was enough to get him killed," Osgood said. Caesar had pushed the envelope for some time before his death. "Caesar was the first living Roman ever to appear on the coinage," Osgood said. Normally, the honor was reserved for deities. He notes that some historians suspect that Caesar might have been attempting to establish a cult in his honor in a move towards deification. It is unclear if Caesar was aware of the plot to kill him on March 15 in 44 B.C. But Caesar was not oblivious to the mounting danger of a backlash, noted Charles McNelis, an assistant professor of classics and Osgood's colleague at Georgetown University. The plot's conspirators, who termed themselves "the liberators," had to move quickly. "Caesar had plans to leave Rome on March 18th for a military campaign in Parthia, the region around modern-day Iraq. So the conspirators did not have much time," McNelis said. Whether or not Caesar was a true tyrant is debated still to this day. It is safe to say, however, that in the mind of Marcus Brutus, who helped mastermind the attack, the threat Caesar posed to Julius Caesar's bloody assassination on March 15, 44 B.C., forever marked March 15, or Ides of March, as a day of infamy. The phrase came to represent a specific day of abrupt change that set off a ripple of repercussions throughout Roman society and beyond. Photograph by Albert Moldvay, copyright National Geographic Society More Information Roman Calendar During the time of ancient Rome, each month began with the calends, from the Latin term meaning "proclaim" or "call." According to N.S. Gill, an ancient and classical history expert who writes for About.com, the term referred to the announcement of the first sighting of the new moon and was also associated with the day interest was due. Following the calends came the nones, which marked the first quarter moon. Its meaning ("nine") was derived from the term for the Roman nine-day week, nundinae. One nundinae after the nones came the ides. The term, which means "to divide," designated the occurrence of the republican system was clear. Brutus's involvement in the murder is made tragic given his close affiliations with Caesar. His mother, Servilia, was one of Caesar's lovers. And although Brutus had fought against Caesar during Rome's recent civil war, he was spared from death and later promoted by Caesar to the office of praetor. "Caesar had always … tried to cultivate talent that he saw in younger people," Osgood said. "And Brutus was no exception." Brutus, however, was torn in his allegiance to Caesar, Osgood noted. Brutus's family had a tradition of rejecting authoritarian powers. Ancestor Junius Brutus was credited with throwing out the last king of Rome, Tarquin Superbus, in 509 B.C. Ahala, An ancestor of Marcus Brutus's mother, had killed another tyrant, Spurius Maelius. This lineage, coupled with a strong interest in the Greek idea of tyranicide, disposed Brutus to have little patience with perceived power grabbers. The final blow came when his uncle Cato, a father figure to Brutus, killed himself after losing in a battle against Caesar in 46 B.C. Brutus may have felt shame over accepting Caesar's clemency and obligation to do Cato honor by continuing his quest to "save" the republic from Caesar, Osgood speculated. It is this moral dilemma that has caused debate over whether or not Brutus should be branded a villain. Plutarch's Life of Brutus, Osgood noted, is quite sympathetic in comparison to surviving documents naming other enemies of Caesar and his successors. Shakespeare later used Plutarch's Brutus as one of the bases for his play Julius Caesar, where Brutus is portrayed as a tragic hero and Caesar as an unequivocal tyrant. The poet Dante, however, took a different stance: Brutus, in killing the man who spared him, was doomed to the lowest levels of hell. "He's perceived not as a liberator but [as] somebody who threatened the stability of the political system," McNelis said. Scholars disagree on just who was the on the side of "good." McNelis believes neither side is entirely in the clear. "We need to realize that we're dealing with very brutal and ruthless men on both sides." In the end, the legacy of power Caesar established lived on through his heir Octavian, who later became Rome's first emperor, also known as Imperator Caesar Augustus. The Ides of March remained a pithy reminder to future rulers, according to McNelis. "Octavian seems to have been aware of the problems of presenting himself as Caesar had. … The Ides became a lesson in political self-presentation," he said. the full moon. The ancient Roman calendar fixed the calends on the 1st, the nones on the 5th or the 7th, and the ides on 13th or the 15th, Gill said in an email interview. The months of March, May, July, and October, the longest months at 31 days, held the nones on the 7th and the ides on the 15th. For all other months the nones fell on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. The one exception to the 31-day rule is January. While it has 31 days, it used to have fewer and so was treated as a "short" month.