Document

advertisement

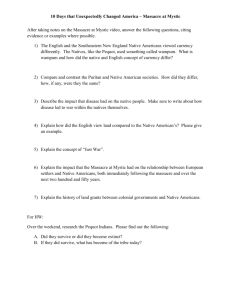

HST3034 – The Massacre of St Bartholomew – and its Aftermath Presentation 8 The Enigmas of a Massacre • Why was it so extensive? • Why did it occur in the immediate aftermath of a royal marriage? • Why did it occur in a period of peace? • Why did the monarchy accept responsibility for the massacre? There is a gap between those contemporary sources who were witnesses (few) and those contemporary sources who claimed to know what happened (large). Among the few, even fewer are reliable witnesses. They include – -Filippo Cavriana – an Italian physician from Mantua in the entourage of the duke of Nevers -Tomasso Sassetti – an Italian informer, probably working for Francis Walsingham, English ambassador in Paris, and resident in Lyon - Italian ambassadors at the French court (Michiel and Cavalli for Venice, Salviati for Rome, Petrucci for Florence) The Massacre as Event • Began in Paris on the early morning of Sunday 24 August 1572 with well-armed catholics circulating through the city wearing white armbands, circulating around houses with known protestants, killing them in cold blood and carrying their bodies to the Seine. Barricades were erected to make it impossible to move around the city, and the gates were closed • Tocsin sounded before daybreak at St Germain l’Auxerrois, followed by other city parish churches and the killing amplified in scope. Armed catholic guards patrolled the streets, controlling those who tried to move through them, killing suspects on the spot • Mass killing continued for three days. Although the paroxysm died down thereafter, there are sporadic murders through to Saturday 30 August • We do not know how many victims were killed in the capital. Contemporary accounts vary between 1,000 and 100,000. We know how much was paid to the gravediggers at the cemetery of the Holy Innocents for burying the bodies of those carried down the Seine and washed up lower down the river (= 1,825 bodies). There might have been c. 3,000??? Killed in Paris • The event was copied in up to 15 similar massacres in other French cities (bringing the total dead to 10,000????. St Bartholomew was not an ‘event’ but a ‘season’ (Michelet) The nebulae of provincial massacres in the wake of that at St Bartholomew in Paris, 24 August 1572 An Unpredictable Event • The Peace of St-Germain (Pacification of 1570), signed on 8 August 1570 • The Royal Entry into Paris, 29 March 1571 • The Ceremonies for the marriage of Henri de Navarre with the king’s sister, Marguerite de Navarre, 18 August 1572 • The Attempted Assassination of the Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, 22 August 1572 Trying to explain the unpredictability of the massacre, contemporaries (protestants mainly, but also catholics) made sense of it by interpreting it as part of a premeditated plot. The peace had been a sham. The marriage of Henri de Navarre constituted a lure. The attempted assassination is the proof of a plot. The massacre is the sign that the intention was to eliminate protestants from the capital. If it was a plot, there had to be plotters…. Those held responsible for the Massacre • Catherine de Médicis – protestants created a ‘black legend’ of the Florentine queen, influenced by Machiavelli, with a taste for the black arts of magic, and a single-minded desire to hold on to power at all costs; still echoed in modern accounts (Mariéjol: modern biographies of Catherine) • Philip II and the Papacy – making use of ‘dupes’ in France (Guises, the magistrates in the Parlement of Paris, etc). It was an international conspiracy, orchestrated to prevent France coming to the aid of the Dutch rebels (Nicola Sutherland: Jean-Louis Bourgeon) • The Guise Family, with the active collaboration of the king’s brother, Henri duke of Anjou (later Henri III) (Janine Garrisson) • No one – it was an ‘event without a history’ becoming (after the event) ‘a history without an event’. It was a ‘love crime’ begun by those around the king who believed that the only way to ‘save the peace’ was to ‘eliminate (selectively) those who threatened its continued existence’ (Denis Crouzet) Everyone agrees:-That responsibility for the assassination of Gaspard de Coligny may be different from responsibility for the massacre - That the key difficulty is to explain the extraordinary volte face between the marriage and the massacre The Fragile Pacification of 1570 The first peace with the ‘oubliance’ clause (Clause 1, Potter, p. 118) ‘First, that the remembrance of all things past on both parts, for and since the beginning of the troubles….shall remain as wholly quenched and appeased, as things that never happened’ And ‘injunction to fraternity’ clause (Clause 2) ‘Forbidding also our subjects of what estate or quality woever they be, that they renew not the memory thereof, to take hold, to revile, or provoke other, by reproaching them with things past, to dispute, to despise, to quarrel, to outrage or offend either other in word or in deed; but to keep themselves in bounds, to live peaceably together as brethren, friends and fellow-citizens, upon pain that the offenders be punished as breakers of the peace’ The Consequences of the Pacification of 1570 • The legacy of several years of intense violence not addressed, but stifled (Monluc – Potter, p. 129) • Noble feuds and factions officially ‘outlawed’ by royal law, and therefore not given a means of being resolved (especially Guises vv Coligny: royal declaration of Colingy’s innocence on 27 March 1572, recognised formally by some members of the Guises family in May-June 1572) • The issue of the protestant attacks upon the monarchy (as widely seen by catholics after the ‘Surprise of Meaux’ swept under the carpet) • Difficult problems of protestant war-debts, especially to German mercenaries. Coligny became their spokesman, and arrived at court in October 1571 • Popular catholic opposition to the pacification, evident in incidents at Rouen, Lyon and in Paris … Was the pacification of 1570 partly responsible for the events of 1572? The ‘Gastines Affair’ Philippe and Richard de Gastines were protestant merchants in Paris, living at the corner of the rue des Lombards and the rue St-Denis in Paris. Their house was used for clandestine protestant worship during the third civil war. One of these meetings was discovered by the Paris municipal authorities. In June 1569, the Gastines were condemned to death and executed and their house knocked down with explicit orders from the Parlement to erect nothing in its place but a large stone pyramidal cross in expiation of what had stood on the site. Gaspard de Coligny demanded and obtained royal letters of 7 October 1571 to have the cross and pyramid taken down The Parlement and municipal authorities refused to comply. It was eventually agreed to remove it to the cemetery of the Holy Innocents. But catholic crowds frustrated the workmen and the event was interpreted as part of a ‘bad omen’ for the future… Jean de La Fosse, parish priest at St-Germain de l’Auxerrois November 1571… ‘Everyone was amazed at the string of edicts which were quite to the disadvantage of the Catholics….There was much talk of witches and warlocks and it was said there were more than 30,000 at work, that the men were marked behind the ears and the women on the thighs. Many were arrested amnd [it was said that] even the king of the witches had been taken and sent to the royal court, where he performed his sorcery in the presence of the said lord [Coligny]’ [Potter, p. 132] Matrimonial Politics – Cementing Peace • A recognised means of dynastic reconciliation in the sixteenth century • Provided a vehicle for ‘oubliance’ of past differences – one in which ‘peace’ was cemented by ‘love’. • The king’s marriage to Elizabeth of Austria had already been agreed, and took place in November 1570, seen as linking the Valois and Habsburg dynasties • Four potential bridegrooms:- Henri de Condé (Louis’ young son) and his cousin Henri de Bourbon, king of Navarre - Henri duke of Anjou and François duke of Alençon, the king’s younger brothers • Several potential brides, including Queen Elizabeth I, Marguerite de Valois (the queen’s sister), and Mary of Cleves The ‘Triumph of Winter’ Antoine Caron’s allegorical painting, possibly from 1571-2, part of a series depicting royal ‘triumphs’ in which the ‘frosty’ and reluctant celebrations may reflect the difficulties of making peace in the immediate aftermath of civil war The ‘Triumph of Spring’ The complementary picture to the last, depicting the neo-platonic, magical charms of love as ‘winter’ becomes ‘spring’. The bridegroom awaits in the temple of Diana (centre) whilst the bride arrives (bottom right) A Problematic Marriage • Henri de Bourbon, king of Navarre and Marguerite de Valois: the union of the Bourbon and Valois; the cementing of the largest fortune outside the crown with the monarchy. BUT -They were close cousins and it would require a papal dispensation - Henri de Navarre’s mother was strongly opposed to the match (it was only negotiated after her death in May 1571) - it was a ‘mixed marriage’ across the confessions (also required papal approval) - difficulties of ‘celebrating’ the marriage in these circumstances. Henri de Navarre and his protestant retinue attended the marriage ceremony (but dressed in ordinary attire) and then left the cathedral whilst Marguerite de Valois celebrated a nuptial mass alone - papal approval was not forthcoming and Catherine de Médicis gambled on a de facto marriage forcing the papacy’s hand Coligny’s Return to Court, September 1571 Gaspard de Coligny returned to the court at Blois in September 1571 (extensively described in Potter, 132-3). Probable that Coligny exaggerated his influence over the king to satisfy his fellowprotestants But evident that he had a clear programme for the reform of the kingdom (watered down version of that presented in 1560-1 at the estates general of Pontoise?) And that he believed that reform and pacification within France was best supported by a foreign campaign to unite the realm and ‘channel’ the forces of violence outside the kingdom. Such a campaign had to be just and reasonable. Supporting the defeated Dutch rebels would be both. A memorandum of June 1572, probably prepared by Philippe Du Plessis Mornay for Coligny, was discussed at the royal council (Potter, p. 134) An Elaborate Game of Bluff • From April 1571, Charles IX in extensive contact with Louis of Nassau and the other exiles from the Netherlands, with plans for a conjoint invasion of the Netherlands, possibly with English support • These plans and contacts were known through spies’ reports in Madrid. But Philip II’s ambassadors ‘affected’ to be ignorant of them because they did not want to push the French monarchy into open support for the rebels • Charles IX and his ministers continued to deny officially that there were any contacts or plans, even though… • Spain reinforced its troops levels in the Netherlands in the spring and summer of 1572 in anticipation of such an invasion; and France did the same • Unlikely that the French council committed itself to undertaking any invasion in the summer of 1572. The opposition around the council was considerable (Morvillier and Tavannes, Potter, pp. 133-135). Unlikely that Coligny was assassinated on the order of Philip II? Coligny’s Attempted Assassination, 22 August 1572 • The assassination was attempted in broad daylight in a street close by the Louvre, as Coligny left the royal council to return to his lodgings on foot • It had clearly been carefully planned – horses were ready for the get-away • It failed to wound him fatally and he was able to identify the house where the shot came from. Members of his entourage went in hot pursuit of the assassin but failed to catch up • The assassin was quickly identified as Charles de Louviers, seigneur de Maurevert, a nobleman from the Hurepoix (region between Melun, Fontainebleau and Provins). He had been brought up as a page in the household of the duke of Guise, but joined Condé’s army subsequently. He was already implicated in two murders, of which the second was for having killed one of Coligny’s lieutenants Was Maurevert a hired assassin? We do not know The King’s Reaction to the Attempted Assassination of Coligny ‘The King, informed of everything, went to visit the Admiral after dinner, with the Queen Mother [….] To honour him the more, the King ordered his doctors and surgeons to care for him constantly, because he had wanted none who were Catholics. They talked to him for a while and consoled him and prayed him to come to the castle so that the King might more easily visit him; but he, with gentle excuses, refused their offer […] The last words that the Admiral spoke to the King were to demand justice for the attempted assassination and to beg him strongly [….] that it was essential to start war against Philip; otherwise it would not be long before he had civil war in this kingdom more ferocious than ever, because he would no longer be able to restrain the nobility in the business, so determined were they to fight.’ [Cavriana’s account of the events leading up to the Massacre of St Bartholomew, 27 August 1572 – Potter, p. 139] Interpreting The Events of 22-24 August 1572 • • • • • Charles IX attempted to defuse the possible Huguenot reactions to the assassination (personal visit; assurance of an investigation; offer of surgeons; letters of explanation to the provinces; Huguenot nobles and high command lodged for their safety close by, and in the Louvre) Some of the Huguenot nobility seem to have discussed some revenge killings for the attempted assassination (Cavriana: Potter, p. 139-140) Some members of the royal council (Catherine de Médicis, Anjou, Guise, Birague, etc) feared for the king’s safety and seem to have planned, at some stage on 23 August in the course of several informal meetings, none of them documented, a ‘tactical elimination’ of leading protestants. It is probable that they used the arguments of the king’s safety, as well as the possible influence of the Admiral upon the direction of foreign policy as arguments in favour of such an extreme measure (Sassetti, p. 141) There is no sign that the king gave orders for such an attack. But he did tighten the security of the city (Potter, p. 142) and instructions were given by Guise (Potter, p. 143) to undertake preparations which seem to have been a part of such a strategic elimination. It is clear from all quarters that the strategic elimination of the Huguenot ‘high command’ got out of hand… Coligny’s Murder Became written up in the traditions of protestant martyrology: a patient, stoic, defenceless death The Geography of the Massacre Centres of Protestant in Paris Nobility in Paris The Louvre, where the king was in residence, and where some Huguenots were in residence The rue de Béthisy, where Coligny was assassinated, and close by where his retinue was stationed The Faubourg St-Germain, where many Huguenot nobles had temporary residence for the nuptial ceremonies The Social Geography of Paris and the Massacre Centres of Massacre The rue St-Denis – major commercial articulation of the city The bridges of the river (blockaded by barricades) The Latin quarter (student residences and university) Towards the river among the artisanal quarter of the place de Greve The Monarchy’s Implication in the Massacre • Orders issued in the crown’s name to carry the massacre to the provinces – but contradictory (Potter, p. 132) • Monarchy implicated sufficiently in the events leading up to the massacre for Charles IX to be forced to claim the event ‘officially’ as carried out under his orders for his own protection (Potter, p. 145-6) - The formal session of the Parlement of Paris on 26 August , where ‘the king declared, with grave words, some of the reasons which had led him to carry out such a killing of the Huguenots’ - Royal declaration of 28 August that ‘what was done was by his express command’. A ‘State Crime’? • The Monarchy no longer a Mediator, above Violence, but a Monarchy of Violence • But not a successful Coup d’Etat. Huguenot nobles in the faubourg St-Germain escaped to the south and reinforced their military position in strongholds (Montauban, La Rochelle, Nimes, etc) • And publish theoretical arguments for resistance to established authority, many of which had already been thought through before 1572 • But a significant event on the long-term evolution of French protestantism. Many protestants converted to catholicism out of fear of reprisal, especially in northern France, where protestantism was marginalised after 1572