Industry/business/functional experience

advertisement

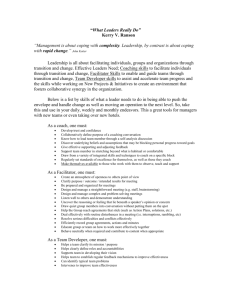

How To Choose An Executive Coach How To Choose An Executive Coach H TABLE OF CONTENTS: It’s Not All About Certification 3 Key Coach Roles And Capabilities 4 Roles The Coach SHOULDN’T Play 8 The Issue Of “Fit” 8 The Issue Of Credentials 9 Conducting A Dialogue With Coach Candidates 10 Being A Powerful Participant In The Coaching Relationship 10 Summary - Key Dimensions For Assessing A Potential Coach 11 CHAPTER 1: It’s Not All About Certification If you’re interested in becoming a more effective leader, or helping someone in your organization be more effective, you may be considering hiring an executive coach. You’ll want to know you are choosing a competent and qualified person, and one who is a fit for the particular situation. And we want to equip you with the tools for making the right choice. Many executives and brokers of coaching jump into the selection process through referrals from colleagues, or they choose the first coach they interview, without considering what they are looking for or how to determine whether they’ve found it. It can be the case where the boss or HR manager will send a few coaches to the executive and ask him to choose a coach based on “fit.” It is useful to give the executive the final choice of a coach, but it’s important to give him* and the other brokers in this process a little help in thinking about what to look for and how to assess for it. In this guide, we’ll talk about key aspects of the coaching role, and give you tools and frameworks to help you collect the information you need and decide whether a potential coach can help you get where you want to go. • * We’ve addressed the pronoun dilemma in this article by referring to the executive as “he” and the coach as “she.” By no means does this reflect any values or beliefs about the actual or ideal gender of executives and coaches // Page 1 How To Choose An Executive Coach It’s Not All About Certification In recent years, we’ve been hearing a lot of emphasis on certification as a criterion - often the sole criterion - for choosing coaches. If you Google “coach certification” you will find 16 million results. “Executive coach certification” narrows it down to 770,000. You can find certification programs that cost less than $400 and require 4 days or less to complete. The most important thing to know is that, in the field of coaching, nobody certifies the certifiers. If you want to know about your physician, you can go to a Medical Association. If you want to know about your plumber or electrician, there are governmental agencies charged with certifying plumbers and electricians. In coaching, there is no certifying agency universally recognized as legitimate. With the boom in coaching in recent years, some certifying agencies have gotten in the business because they recognized a market opportunity, not necessarily because they had deep knowledge or a long track record in developing skilled coaches. Some certifying agencies provide rigorous training and others do not. Even the definition of what’s “rigorous,” what capabilities and skills a coach should possess and how to develop these, is not universally agreed on. Another problem with using certification as your criterion is that many competent coaches – coaches who came of age before the current focus on certification, and/or coaches with other relevant academic and practical training – don’t bother with the formality of certification. Conversely, many inexperienced coaches have gotten certification, but that may be the only coaching-relevant training they have. You are right to want a capable and trained coach, but relying on certification as the measure of capability trivialises your search. Coach certification also discourages you from taking responsibility for selecting a person with the fit, skill, and presence that will work for you. **Certifying agencies are self-styled “authorities”, and when people accept the judgments of an authority without applying their own judgment, they remain dependent on others’ authority instead of becoming their own authority. Learning to know and trust one’s own judgment is itself a developmental step that a good coach should help an executive make. ____________________________________________________________________________ ** This point was nicely made by David McCleary in his 2006 article “Executive coach certification and selection: a contrarian’s viewpoint,” Development and Learning in Organizations, vol. 20, issue 4, pp. 10-11. // Page 2 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 2: Key Coach Roles And Capabilities So, how do you take matters into your own hands and assure yourself that you have a capable coach who will help you accomplish an executive’s and an organization’s goals? We’ll talk about the following strategies for getting the coach you need. • Educate yourself on the important competencies and skills a coach needs, and what to avoid. • Hold an open dialogue with candidates, to surface the information you need in order to decide. • Take responsibility for participating in coaching in a way that increases the chances of success. Below are several important elements of the coaching role. You will want to be prepared to assess a potential coach’s ability to play these roles in your initial meeting with her. You may also need to supplement that meeting with other information, such as written documentation of a coach’s approach and references from previous clients. // Page 3 How To Choose An Executive Coach Balance Support And Challenge It’s difficult in the best of situations for most executives to show uncertainty, express fear, ask for help. However, for development to occur, it’s critical for the executive to do these very things. This is more likely to happen if the coach can create a safe environment in the relationship. A coach does this, in part, by showing that she “gets” the executive – listens to and understands his deep interests, values, and concerns – and respects these. Such understanding enables executives to feel accepted, to be open about thoughts and feelings and to be willing to try new behaviours This connection enables the coach to help the executive focus on reaching his true goals and addressing his true concerns. A subtle effect of this acceptance is that the executive realizes it is okay to be his flawed self, and this realization can help him stop doing things that are ineffective, but that are driven by the desire to appear perfect. (The other necessary ingredient for this safe environment is the coach’s keeping commitments about confidentiality and privacy – which we’ll discuss later in this guide.) On the other side of this balancing act, the coach should not just be a cheerleader. She must also provide the challenge that is needed to get the executive out of the comfort zone of habitual behaviors and perceptions. She must help the executive face – directly and non-judgmentally – the unintended impact of his actions, and probe the motives and assumptions underlying those actions. The coach must be willing, thus, to lead the executive into places that are uncomfortable, because there is a level of learning about oneself that can only be reached with some discomfort. // Page 4 How To Choose An Executive Coach An Effective Coach Should Have Insight. One tool a coach can use to challenge the executive and help build self-awareness is her own direct experience with the executive. The way an executive treats the coach reflects the way he treats others in the organization, though the exact parallel may depend on how he perceives the coach – as a sub- ordinate, for example (because she is not part of the hierarchy), or vendor (because she is an external consultant), or an authority figure (if she has a relationship with the executive’s boss). Perhaps her gender, race, or other personal characteristics influence the way he interacts with her. An effective coach should have the insight and the skill to play back to the executive the relevant behavior. Example One executive had received feedback from co-workers that he was insensitive to others’ needs. Addressing this was one of the goals of his coaching project. During that project, he repeatedly cancelled meetings with his coach, including meetings she had specifically traveled to attend, without notifying her in advance and without even acknowledging the cancellations when they next saw each other. This was relevant feedback for the coach to share with him. Together they could probe (without judgment) what the executive was thinking, or not thinking, when he chose to schedule something else during his regular coaching meeting time, or when he chose not to inform the coach. This helped him become more aware of how he was behaving similarly with his colleagues. An Effective Coach Should Have Emotional Competence The coach must have the emotional competence, the ability to separate herself from her role, to allow her to raise such issues not out of anger but for the purpose of learning. She must also have the capacity to be authentic – to talk straight with the executive about her observations and reactions. // Page 5 How To Choose An Executive Coach Help The Executive Create Feedback Loops Getting the executive new insight into his style and impact is perhaps the most basic and universal coach activity. Most coaches conduct some kind of 360-degree feedback as part of their work with an executive. This is an important element, because most executives don’t get authentic feedback about how they’re perceived or the effects of their behavior on others and they don’t reflect much on the underlying aspects of their character or personality that drive their behavior. Getting this feedback is often a transformational experience for the executive, as it reveals blind spots and unintended effects. Initially, the coach may serve as the conduit for feedback from colleagues, since it’s rare that others share authentic feedback with executives. She must solicit that information from colleagues in a way that satisfies their needs for confidentiality and manages any anxiety they might have about divulging information they consider risky. This requirement means establishing clear agreements about how the information will be used, and whether and how a respondent will be identified specifically – and never losing track of those boundaries. Over time, the coach’s role is to help the executive build the skills and relationships to directly ask for feedback on an ongoing basis. A good coach will not seek to foster dependence on the executive’s part, but rather will want to teach him how to manage his own development on an ongoing basis. Teaching him how to get his own feedback will involve the coach forming the initial links with colleagues – possibly beginning with the initial assessment interviews – and helping the colleague develop skill and comfort at framing useful feedback. // Page 6 How To Choose An Executive Coach For example, the coach can help the colleague distinguish between a specific description of behavior (which is useful) and a vague judgment (which is not). The coach will also help the executive plan how he will directly ask colleagues for feedback, and how he will manage the ensuing conversation – for example, how to receive the feedback in a way that’s not defensive. The ultimate goal is for the executive to build enduring feedback channels. Incidentally, this process can be transformative to the executive’s work relationships. Finally, the coach can help the executive learn how to make sense of the feedback received – deciding what is relevant and valid, choosing which issues to address, and deciding how best to address them. This activity is itself developmental, because it helps the executive become comfortable with forming his own judgments about others’ perceptions and expectations. Help The Executive Clarify Purpose And Value The coach’s role in this goal is, first, to help the executive honestly articulate his core interests and values. This includes clarifying how he wants to change and develop, what he wants from his career and life, and what purpose and objectives he has in his current role. It also includes helping him understand his wants, needs, concerns, and boundaries in any particular situation. Second, the coach can help the executive act consistently with that purpose and values. Executives often think it is not legitimate to pursue their own interests in the organization, but they fail to recognize that everyone is pursuing their own interests, including doing the best job in their role as they see it, and trying to optimize the objectives of their group as they see those objectives – but also including building their careers, being seen as effective, and other more “personal” interests. Once the executive becomes more comfortable identifying his true interests, the coach can help him behave more consistently with those interests in every moment. Ultimately, any executive is most powerful when basing decisions on what he cares most about - his values, purpose, and vision. // Page 7 How To Choose An Executive Coach Structure The Development Process To support the development of desired behaviors, the coach must help the executive manage and progress through the entire development process. This process generally involves a number of steps including • establishing a working agreement or contract • getting input from others • reviewing feedback • creating a development plan • holding regular coaching meetings to practice new behaviors • implementing these behaviors in one’s daily work • assessing the project The coach should be able to provide the executive with a clear road map for how the process will work, and then help keep the process moving over time – especially when the executive is apt to let it slide because of urgent work matters or perhaps because of the natural resistance to change. The coach should also, as part of the coaching engagement, help the executive identify and stay focused on specific desired outcomes. This is an exercise in aligning actions with purpose, but it also instills a discipline for intentionally conducting a conversation with clear objectives and then testing the accomplishment of the objectives. // Page 8 How To Choose An Executive Coach Increase The Executive’s Thinking Complexity For complex leadership challenges, development is not a straightforward matter of learning and practicing new skills. Becoming more effective as a leader, in an enduring way, involves shifting one’s mindset. Broaden Perspectives The coach’s purpose is not to teach skills, give advice, or provide input into decisions (though there is a role for teaching skills, as will be described next). Rather, she is there to conduct developmental conversations with the executive that help broaden his perspective on the issues around him - challenges, relationships, decisions, actions. Break Out Of Ingrained Viewpoints The key coaching activity to accomplish this is asking questions, to unpack how the executive sees situations and why. This process of questioning is intended to help the executive break out of the limits of ingrained viewpoints and realize that his assumptions are just that – assumptions, not facts. This will allow him to build less limiting assumptions, consider new information, and take more effective action. // Page 9 How To Choose An Executive Coach Teach Concepts And Skills. There is some value in teaching skills as part of a coaching relationship. Often, executives are so immersed in the world of action that they never develop a clear lens or model for what their role is all about. An executive may become consumed with firefighting, believing that he must deal directly with every issue that crosses his desk. He may be new to his broad role and overwhelmed by it. The coach can help him step back and get a clearer picture of what is and is not a part of his role. The coach should have a model of leadership – what leadership means, the key tasks or challenges, what it takes to be effective, and key competencies or skills. For example, in our group, leadership is about getting the shared commitment of a group of people to a common purpose and mobilizing their energy towards it. Key skills include collaboration, expectation management, influencing, conflict management, and developing others. Whatever a coach’s guiding model, she should be able to teach the relevant skills to the executive and help him implement them in daily interactions. Help The Executive Put In Practice New Behaviors To Achieve His Goals. Executive coaching for performance can go very deep into one’s makeup as a human being, but it also needs to be very pragmatic. The ultimate goal is to help the executive translate new ways of seeing the world into new and effective behaviors. A coach should value this concrete translation. If she does, she will focus coaching conversations on concrete work challenges the executive is facing today, and those he anticipates tomorrow. This is where the rubber meets the road in coaching – through concrete work challenges, exposing the executive’s thinking process so that hidden roadblocks and motivations are surfaced, and translating insights into specific action related to the executive’s goals. // Page 10 How To Choose An Executive Coach Maintain Confidentiality To be effective, the coach must maintain relationships based in trust. The coach must be able to maintain her boundaries – to keep confidential the information she gets from each client in whatever manner has been agreed, and to keep confidential the information that other colleagues provide along the way – for example, during assessment interviews. If a coach wishes to share information from a client or colleague with anyone else, she must first get the consent of that person. Influence Others’ Views Of The Executive. A coach should practice what we call “embedded coaching.” This is especially important, but is not universally present in coaches’ practices. In performance coaching it is not enough for a coach to help the change his behavior – she must also help others see that change. To do so, the coach must engage with the executive’s colleagues, to help them see the issues more broadly, get them involved in his development, and help them change how they behave with him. The coach should not be divulging the executive’s secrets in these meetings. She should be discussing colleagues’ perceptions and judgments of him, and testing those colleagues’ willingness to look more broadly at the biases in their views and their own contribution to issues. She may share with the executive what she learns in these conversations – and she should be explicit with colleagues if she intends to do so. // Page 11 How To Choose An Executive Coach Here are some key ways in which you should expect a coach to practice “embedded coaching”. If a coach does not raise this aspect of her role and associated activities in initial conversations, you should test with her whether she is willing to engage in these essential activities. • Coach the executive’s relationships, not just the executive. • Challenge assumptions that the entire problem resides in the executive. Help others consider structural/situational contributions. Help others consider their personal contributions. • Contract with key colleagues around... ...their desired outcomes of the process. ...their willingness to share feedback. ...their willingness to participate in conversations about new mutual expectations. • Facilitate conversations between the executive and colleagues. Share coaching insights and development plans. Negotiate new expectations – in both directions. Solicit ongoing feedback from colleagues on relevant behaviors. Evaluate Coaching Outcomes. Brokers are likely to have an interest in assessing the impact of coaching engagements, and the coach should be able to describe a method for providing this assessment without violating the executive’s confidentiality. In addition, and separately, it’s important that the coach and executive jointly evaluate the outcomes of the coaching process relative to the executive’s goals. This helps to fix the insights gained in the executive’s mind, and also serves as a starting point for his continued self-development. // Page 12 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 2: Roles A Coach SHOULDN’T Play This discussion of the coach’s role has surfaced several roles that are not appropriate for a coach, be- cause they do not build the executive’s capability for independent action in the service of his purpose and goals. Some of these are common and alluring traps for a coach, but an effective coach should never succumb to them. They include ... • Cheerleader – telling the executive everything he does is great • Therapist – helping the executive strictly with personal adjustment and psychological issues, independently of his performance in the organization and of others’ expectations. • “Shadow Manager” – advising the executive on business decisions or stepping in and acting on his behalf • One-sided Advocate – of the executive’s point of view, the broker’s point of view, or the viewpoint of other stakeholders who have expectations of, or conflicts with, the executive // Page 13 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 3: The Issue Of Fit The notion of “fit” is a complex and loaded one. If you find yourself thinking about this issue in relation to potential coaches, it can be useful to deconstruct what you really mean by it. Here are some meanings that commonly underly executives’ and brokers’ concerns about a coach’s “fit”. Industry/business/functional experience – Often, organization leaders believe their industry business/function is unique, and assume a coach must have worked in the industry to truly understand their challenges. Indeed, it is critical for a coach to understand the business and strategic challenges an executive faces. However, in our experience, at the level of broad patterns, there are more similarities than differences across industries, and good coaches learn to quickly diagnose the specific business/industry patterns through concrete conversations about an executive’s challenges. Cultural Fit – It matters that a coach tunes into your organization’s culture, so that she can navigate smoothly and understand the behavior patterns she encounters. However, for your coach to help the executive and the organization in a more-than-superficial way, she should be able to see the culture for both its upsides and its downsides. A “kind and caring” culture can also be an “indirect communication” culture, and your coach can help the executive and those around him see ways in which they want to change the aspects of their culture that don’t serve them. Personal Style – It’s important to talk with several potential coaches and get a feel for what resonates best. Bear in mind, sometimes differences help. For example, laid-back, gentle, non threatening coaches can sometimes pierce the armor of hard-charging, aggressive executives more easily than forceful coaches, who can potentially provoke competitiveness or defensiveness. And sometimes similarities help. If a coach can empathize with an executive’s style issues, she can use that empathy to help. For example, coaches who have overcome their focus on rationality and being right can connect with executives who are challenged by this focus. Race And Gender – You may feel more comfortable with, or feel you can get more insight by working with, a person of your same or a different gender, and your same or a different race. Sometimes, where an executive could get the most learning isn’t where he will feel most comfortable. A male executive who has been told he does not work well with women, or vice versa, might benefit most by working with a different-gender coach so that he can learn from his reactions to the coaching relationship. // Page 14 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 4: The Issue Of Credentials In the field of executive coaching, there are no well-trodden traditional career paths or educational backgrounds. Most coaches come to the practice after a gradual evolution from related areas – for example, an internal Human Resources role specializing in leadership development or organizational effectiveness, or an external consulting role in organization change or leadership training. Some individuals come to coaching from careers in counseling or therapy. Education In terms of education, generally it is useful for coaches to have formal education in a relevant field such as business, psychology (industrial-organizational, clinical, or counseling), or organizational behavior. A graduate degree in the field indicates deeper knowledge. Training Specialized training, such as certificate programs in executive coaching or organizational change, can supplement an educational background that is not directly relevant. Consider the source of the certification. For example, programs offered by Universities are intensive and thorough. What matters most is that through education, work experience, and continued training, the coach has come to understand both individual and organizational dynamics. Each area of expertise is necessary but insufficient on its own. It’s impossible to help a person change ingrained behaviors without understanding the dynamics of individual personality and how people develop. Coaching Is Not Therapy, Some clinical insight and perspective is useful. At the same time, it’s also important that a coach have some understanding of how organizations work, what kind of outcomes will be valued from colleagues’ perspectives, and how an executive’s network of working relationships and role demands will affect his development. Some coaches have had experience as managers or executives. That can be useful, as long as they do not think coaching is simply giving advice or sharing expertise. Learning how to be a managerial coach, using a coaching style in leadership, can be great preparation for an external coach. Finally, the best experience for a coach is a lot of practice coaching various individuals in diverse organizations. // Page 15 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 5: Conducting A Dialogue With Coaches When you meet with potential coaches, you will want to cover the following areas. • Your goals for the process – whether you are an executive, broker, or boss • Strategic challenges the executive currently faces • The process the coach follows – objectives, key activities, terms of engagement, confidentiality • How the coach has helped people in similar situations, and how their process will directly address your goals • The coach’s expectations of the executive, broker, and boss • Any questions or concerns you have It never pays to allow aspects of your “agenda” to remain hidden. When a sponsor has already formed judgments about an executive, or an executive is feeling coerced into participating in coaching, out- comes suffer. // Page 16 How To Choose An Executive Coach CHAPTER 6: Being A Powerful Participant In The Coaching Relationship The more an executive puts into the coaching process, in terms of time, effort, openness, and willingness to question assumptions and try new things, the more he will get out of it. This applies to managing the actual coaching process and coaching relationship. It helps to be an active and effective participant in one’s own coaching process, rather than passive. Below are some guidelines. • Clarify and articulate your interests in the coaching process, whether you are executive, broker, or boss. What outcomes do you want? what outcomes do you not want? • Be proactive in selecting a coach and make sure that the coach is capable and has the necessary competencies. • Make sure that you are getting what you want and need at every stage. • Refer to goals and desired outcomes and make sure the coaching work is addressing them. • Raise any issues or concerns that you have with your coach, and seek to diagnose and change what needs to be changed. Participating as a partner and not just as a recipient is also a model of a powerful way to engage with colleagues, regardless of where they sit hierarchically. Simply engaging powerfully in the coaching process can help shift the executive’s way of interacting with others to a more mindful and effective style. // Page 17 How To Choose An Executive Coach Summary Dimensions For Assessing A Potential Coach Sample Indicators Capabilities Balance support and challenge Help create feedback loops Understands executive’s goals and values, without judging • Shows willingness to challenge executive on counterproductive behaviors and attitudes. • • Initially, will get feedback directly for executive • Over time, will help executive develop skills to get own feedback on ongoing basis. Help clarify purpose and values • Inquires about executive’s personal goals and values • Will help executive make choices based on objectives and Principles. Structure the development process • Provides a clear road map for the process, including how activities contribute Increase thinking complexity • Asks questions to help surface and question assumptions and beliefs that drive behavior patterns. Teach concepts and skills Help put in practice new behaviors Maintain confidentiality Influence others’ views of the situation Evaluate coaching outcomes Fit Credentials // Page 18 to desired outcomes. • Brings discipline for linking development activities to purpose and objectives. Shares a model of leadership, including skills to be incorporated into coaching work. Inquires into current work challenges • Links development to day-to-day work and identifies behaviors relevant to work challenges. • Describes approach to confidentiality (executive’s and others’) • Plans to help executive engage with co-workers, to address their perceptions and contributions • Plans to assess coaching impact for organizational purposes • Plans to debrief outcomes with executive, to support continued development • Consider ... Ability to understand strategic business/industry challenges ... Ability to understand, navigate and question culture … Personal style … Race and gender • Consider ...Education and/or specialized training/certification ...Understanding of organizational/individual dynamics … Coaching experience (including managerial coaching)