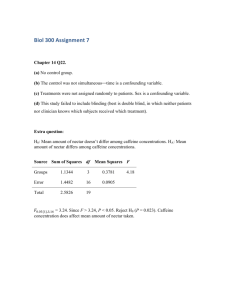

ARG example: another with conflicting data

advertisement

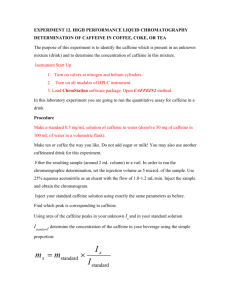

Does Caffeine Consumption During Pregnancy Increase the Risk of Miscarriages or Low Birth Weight in Humans? [authors] An argumentative paper for women of reproductive age A paper for Pregnancy & Newborn magazine The Connection Between Caffeine and Pregnancy: Why You Should Care Women put forth a large amount of energy, time, and money to ensure that their babies are happy and healthy. From numerous doctor visits to restrictive diets, women strive to be the best mothers they can be from the moment of conception. If you are pregnant, may become pregnant, or have a loved one who is pregnant, it is important that you are properly educated on how prenatal consumption can affect an unborn child. Typically, pregnant women are advised to abstain from alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine. While nicotine and alcohol are proven to have harmful effects, caffeine’s effects are less certain. Caffeine could have possible negative effects on an unborn child such as miscarriage, low birth weight, birth defects, early gestational age, and behavioral issues in a child. While we understand that these outcomes can be devastating on the mother and child, this paper will focus on just miscarriage and birth weight. Among the possible effects, miscarriages and birth weights are common for researchers to evaluate throughout the pregnancy and after delivery. Also, by looking at these two possible outcomes, we will be evaluating the effects of caffeine from an extreme risk (miscarriages) to a less life threatening risk (low birth weight). Because these two outcomes are on opposite sides of the spectrum, it allows us to encompass other effects. 1 For example, infants born prematurely or with a birth defect usually are born underweight as well. By examining studies that focused on miscarriage or birth weight we will be able to better understand the effects of caffeine on an unborn child. Through looking at these two outcomes, we will be determining the best conclusion to the question: does caffeine consumption during pregnancy increase the risk of miscarriages or low birth weight? In determining the best conclusion, we analyzed conflicting data from nine studies and one review that included seven studies (Figure 1). These studies examined women who ranged in age, marital status, and health. The researchers monitored the women’s caffeine consumption using a phone interview or questionnaire throughout their pregnancy or after their delivery or miscarriage. We found four studies that looked at the effects of caffeine on birth weight, four studies that looked at the effects of caffeine on miscarriages, and one study, Mills et al., that looked at both miscarriages and low birth weight. In order to understand how researchers arrived at their conclusions it is important to know how they examined caffeine. First, caffeine comes in many forms. The major sources of caffeine are coffee, tea, chocolate/cocoa, medication and soft drinks, the biggest source for most people being coffee. Studies varied in how they quantified caffeine consumption; some used cups and others used converted cups to milligrams. In order to standardize the results, we chose to separate caffeine consumption into categories of low, medium, and high based on milligrams. For our evaluation, we considered a low dose of caffeine to be anywhere between 0 to 150 mg a day. A medium dose of caffeine would be between 150 to 300 mg a day, and a high dose would be 2 anything above 300 mg of caffeine a day. In most cases, one cup of coffee contains about 150 mg of caffeine, a cup of tea contains 40 mg, and a soft drink contains 50 mg (Heller). Another way to understand how researchers reached their conclusion is based on how they interpreted their results. The health of an infant and the success of pregnancies can be influenced by many factors, making it difficult for researchers to focus on the effects of any one substance, such as caffeine. In order to account for the other factors many studies used an adjusted odds ratio (OR). This ratio is calculated from the data in order to “remove” factors that the scientists are not trying to study such as the mother’s alcohol consumption, nicotine intake, or health predispositions. In these studies, the OR indicates the likelihood that miscarriages or low birth weight occurred due to caffeine alone. The baseline value for an OR is 1, which indicates women who consumed no caffeine. As the OR increases, it means that the likelihood of having a miscarriage or underweight baby due to just caffeine consumption also increases. This system can be seen by the graphs on the left in Figure 2 and 3. Another way to interpret the data is to simply take the average birth weights of infants or the percent of miscarriages and see if the numbers are higher or lower due to caffeine consumption. Examples of these different measures can be seen by the graphs on the right in Figures 2 and 3. What Researchers are Saying and What We Think The data regarding the effects of caffeine on miscarriages and birth weight are conflicting and unresolved. Figure 1 shows five studies that examined caffeine’s effect on birth weight and five studies that examined caffeine’s effect on miscarriages. Some of these studies found that caffeine affects miscarriages or birth weight, while other studies found that caffeine does not have an effect. In the Fenester et al. study, women who 3 consumed a high dose of caffeine (300+ mg) had an OR of 2.36, which means they were 2.36 times more likely to have an underweight infant (Figure 2, red). Similarly, in the Cnattingius et al. study, researchers found that women who consumed a high dose of caffeine were 2 times more likely to have a miscarriage (Figure 2). When comparing these ORs to the base value of 1, they are significantly higher and therefore these researchers concluded that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. In contrast, Mills et al. calculated that women who consumed a high dose of caffeine were only 1.15 times more likely to have an underweight infant (Figure 3, purple). Similarly, the Clausson et al. study found that infants had an average birth weight of 8.069 lbs, 8.078 lbs, and 8.00 lbs in women who consumed a low, medium, and high dose of caffeine respectively (Figure 2, green). These averages were almost identical regardless of caffeine consumption. In both these studies, the researchers found that caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. Although, all of these studies monitored caffeine intake and miscarriages or birth weight, they reached opposite conclusions proving the data is conflicting and thus unresolved. Although the data is conflicting, we will analyze the studies thoroughly in order to find if the evidence is stronger for one conclusion than for the other. At this stage of research, the evidence is pointing towards the conclusion that consuming caffeine while pregnant does not increase the risk of miscarriages or low birth weights. This is due to the fact that these studies were typically designed in a more reliable way that reduced the chance for possible errors to occur. Due to the conflicting data, there is an alternative conclusion that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. This is strengthened by the fact that more studies reached this conclusion. However, one very 4 reliable study is far more beneficial in reaching a conclusion than multiple unreliable studies and you will see that throughout this paper. Comparing: The Start of Determining Reliability In determining the reliability of the studies, we compared them in groups based on their conclusions in order to see the strengths and limitations. One group would include the studies that found that caffeine has an effect and the other group would include the studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. First we did a comparison between the different types of caffeine researchers accounted for. As we discussed above, caffeine can come in many different forms. Some studies, such as the Cnattingius et al., focused on nine different types of caffeine while other studies, such as Bech et al. and Armstrong et al., just looked at caffeine in the form of coffee. In Figure 4, you can see that the types of caffeine the researchers accounted for varied widely between all nine studies but not necessarily between each conclusion. The studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight accounted for an average of 4.5 types of caffeine, and the studies that found that caffeine has either effect accounted for an average of 4.2. Since these averages are almost identical, it does not strengthen one conclusion over the other. Another comparison that could impact the reliability of these studies is how they estimated caffeine consumption. In these studies, researchers asked mothers how much caffeine they ate or drank per day. Then for the beverages, the researchers would either keep their answers in terms of cups or convert them into milligrams (mg). A standard cup of coffee can range from 29-333 mg of caffeine due to differences in caffeination or cup 5 size (Heller). This large range can complicate the accuracy of using milligrams or cups as a form of measurement and lead to unreliable results. These studies used different methods for estimating caffeine in coffee and other forms. For coffee some studies, such as Clausson et al. and Cnattingius et al., estimated the caffeine based on how it was made: brewed, boiled or instant. They estimated that there is 115 mg if the coffee was brewed, 90 mg if boiled, and 60 mg if instant. However, most studies just used one estimation regardless of how it was made for coffee and other forms of caffeine and these varied. As you can see by Figure 5, there is a large difference in caffeine estimation between studies. Fenester et al. (Figure 5, green) estimated that there is 47 mg of caffeine in a soft drink while Vik et al. (Figure 5, orange) estimated there is only 13 mg of caffeine per soft drink. The variability in these estimations creates a limitation in all nine studies, which makes it hard to reach a definitive solution. Our hope was to find a trend in the way researchers estimated caffeine and the conclusion that they reached, but there was none. Figure 5 shows that regardless of whether the researchers had high or low estimation of caffeine, it did not dictate if they found that caffeine has an effect or not. Therefore, the ways in which researchers estimated for caffeine did not impact our conclusion. Furthermore, this comparison allowed us to determine if simply using cups rather than converting to milligrams affected the outcome of a study. There were three studies that did not convert to milligrams and kept their data in terms of cups: Bech et al., Howard et al., and Armstrong et al. Two of these studies concluded that caffeine does not have an effect and one study concluded that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weights. Based on this, varying methods involving the conversion of cups to 6 milligrams or just using cups did not impact either their conclusion or ours. Although this did not help us reach our conclusion, it was important to compare these studies in multiple ways to see if there were comparisons that strengthened one conclusion over the other. The Other Side One comparison that weakens our argument is that more studies concluded that caffeine consumption has an effect than concluded that it does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. Out of the five studies that looked at the effects of caffeine on birth weight and the five studies that were included in the review, six studies found that caffeine increased the risk of having an underweight child (Figure 1). Similarly, out of the five studies that looked at the effects of caffeine on miscarriages and the two studies that were included in the review, four found that there was an effect. This means that out of 17 studies total, 10 found that caffeine has an effect on either miscarriages or low birth weight. Typically we are taught that majority rules, and this caused us to originally believe that caffeine has an effect. However, through closer comparisons of these studies we found far more aspects that weakened the conclusion that caffeine has an effect than that strengthened it, which will be shown in the rest of this paper. Would You be Able to Remember a Cup of Coffee Nine Months Ago? A difficulty with all these studies is that they rely on the ability of women to recall their caffeine consumption throughout their pregnancy. The accuracy and credibility of this recall relies heavily on whether the study had a retrospective or a prospective design. A retrospective design is when researchers interview women about their caffeine consumption after their delivery or miscarriage. A prospective design is 7 when researchers interview women at their first prenatal appointment or before conception and then continue to interview them throughout their pregnancy. As you can imagine, it would be more difficult to recall your consumption of coffee, tea, soft drinks, or chocolate over the past nine months than it would be to recall your consumption from last week. Thus, prospective studies are stronger than retrospective studies. We found that studies that concluded caffeine has either effect typically used the less reliable retrospective design while the studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect typically used the more reliable prospective design (Figure 6). Out of the five studies that found caffeine has either affect, the majority were retrospective (four out of five). For example, the Fenester et al. study, did not interview mothers about their caffeine consumption until nine months after delivery. This means that they were asking women to recall all the caffeinated beverages they had drank for the past 18 months! If every woman were to forget drinking just one cup of coffee (150 mg) a week, the researchers’ data would be off by about 5400 mg of caffeine per pregnancy. It is clear that this could lead to inaccuracies. Since the majority of these studies used this design it lessens the credibility of their conclusion that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. In contrast, only one of the five studies that found caffeine does not have an effect used a retrospective design. In this case, the majority of studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect used a prospective design (Figure 6). In the Mills et al. study, they had women fill out a questionnaire about their caffeine consumption at their first prenatal appointment. These questionnaires were then repeated at weeks 6, 8, 10, 12, 20, 28, and 36. This was an extremely thorough assessment and the researchers came to the overall 8 conclusion that “despite [their] intensive surveillance” caffeine does not have an effect on an unborn child. The majority of these studies used similar approaches and reached the same conclusion. Asking women eight times during a nine month period versus one time after 18 months has such a huge influence on the credibility of a study that it swayed us to conclude that caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or low birth weight. The Bigger the Study the Better The number of people in a study is important because the purpose of a study is to reach a conclusion that applies to the whole population. Since researchers cannot feasibly include the entire population in their study, they rely on a group to represent it. The larger this group is the more it will represent the population. Also, by having a larger group, unusually high or low results will cancel each other out and create an average. If a study has too few subjects, this average would be affected by any unusually high or low result. In the end you want to know if the study can be applied to you. If studies have more people in them, they will do a better job of accounting for the population and variability in data, which increases the likelihood that the results found can be applied to you. To see which studies were more representative of the population, we compared group size between the studies. In addition to having a better design, studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect had more people than those that concluded caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. In the studies that found caffeine does not have an effect there were 134,182 women but in the studies that found either effect there were only 89,997 women (Figure 7). Not only did the studies that found caffeine has an effect have fewer women, 98.3% of these women were from the Bech et al. study. Although this strengthens the reliability of this one study, the remaining four 9 studies are very small which weakens the overall conclusion more. Such a small size in these others studies causes the conclusion to be easily affected by unusual results and limits its ability to be applied to the population. In contrast, two large studies concluded that caffeine does not have an effect as opposed to only one study concluding that it does (Figure 8). The Howard et al. study had 97,903 women, and the Armstrong et al. study had 35,848 women. The large number of people in these studies makes the results more applicable to the population. Due to the fact there were two large studies and overall more people in the studies that concluded caffeine does not have effect, we are even more confident in our conclusion. The Big Picture: What Should I Do? Through our evaluation of these studies it is evident that there is not a definitive conclusion. This is an issue that has many different components, which makes it difficult for the studies to be identical and thus harder to compare the studies to understand how the researchers are getting contrasting conclusion. As much as we want to be able to make a definitive conclusion about caffeine’s effect on an unborn child, we cannot. In order to make this claim, we need more studies that have a large amount of people, use a prospective design, and estimate for caffeine in a uniform way. Until we have more studies like this, the best we can do is evaluate the current studies to see where the strengthens and weaknesses lie. Through our evaluation, we found that the studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight were typically more reliable studies and thus, their conclusions were stronger. In contrast, the studies that found caffeine has an effect were designed in a way that allowed for more errors and inaccuracies. These inaccuracies could have impacted their results, thus weakening their 10 overall conclusion. Because of this we concluded that caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. However, the decision to consume or abstain from caffeine while pregnant is up to you. If you want to play it safe, we suggest you do not consume any type of caffeine while pregnant. Regardless of what you choose to do, this paper has given you the tools to make a more educated decision for you and your baby. References Armstrong, B. G., McDonald, A. D., & Sloan, M. (1992). Cigarette, alcohol, and coffee consumption and spontaneous abortion. American Journal of Public Health, 82(1), 85-87. Bech, B. H., Nohr, E. A., Vaeth, M., Henriksen, T. B., & Olsen, J. (2005). Coffee and fetal death: a cohort study with prospective data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162(10), 983-990. Clausson, B., Granath, F., Ekbom, A., Lundgren, S., Nordmark, A., Signorello, L., et al. (2002). Effect of Caffeine Exposure during Pregnancy on Birth Weight and Gestational Age. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155(5), 429-436. Cnattingius, S., Signorello, L. B., Granath, F., Anneren, G., Clausson, B., Ekbom, A., et al. (2000). Caffeine intake and the risk of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. The New England Journal of Medicine, 343(25), 1839-1844. Fenster, L., Eskenazi, B., Windham, G., & Swan, S. H. (1991). Caffeine consumption during pregnancy and fetal growth. American Journal of Public Health, 81(4), 458-461. Heller, J. (1987), What Do We Know About the Risks of Caffeine Consumption in Pregnancy?. British Journal of Addiction, 82: 885–889. doi: 10.1111/j.13600443.1987.tb03908.x Howards, P. P., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Bech, B. H., Nohr, E. A., Anderson, A. N., Poole, C., et al. (2012). Spontaneous abortion and a diet drug containing caffeine and ephedrine: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. PLoS ONE, 7(11), 19. 11 Mills JL, Holmes LB, Aarons JH, et al. Moderate caffeine use and the risk of spontaneous abortion and intrauterine growth retardation. JAMA. 1993;269(5):593-597. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03500050071028. Vik, T., Bakketeig, L. S., Trygg, K. U., Lund-Larsen, K., & Jacobsen, G. (2003). High caffeine consumption in the third trimester of pregnancy: gender-specific effects on fetal growth. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology, 17, 324-331. Vlajinac, H. D., Petrovic, R. R., Marinkovic, J. M., Sipetic, S. B., & Adanja, B. J. (1997). Effect of caffeine intake during pregnancy on birth weight. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145(4), 335-338. 12 Birth Weight Article Caffeine intake does not increase the risk of low birth weight Caffeine intake does increase the risk of low birth weight Clausson et al. Fenster et al. Vlajinac et al. Vik et al. Mills et al. Heller (Review) Total Miscarriage Article Bech et al. Cnattingius et al. Howard Armstrong et al. Mills et al. Heller (Review) Total 4 Caffeine intake does not increase the risk of miscarriages 3 6 Caffeine intake does increase the risk of miscarriages 4 Figure 1. This shows the results from 9 studies and 1 review that looked at the effects of caffeine on miscarriages or low birth weight and their overall conclusion. From this table, you can see that the majority of studies concluded that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages and birth weight. 13 Adjusted Odds Ratio 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 ✔ ✔ Vik et al. Fenester et al. Birth Weight (lbs) Effect of Caffeine on Birth Weight Effect of Caffeine on Birth Weight 8.2 ✖ 8 7.8 7.6 7.4 7.2 7 ✔ Clausson et al. Vlajinac et al. Caffeine Consumption Caffeine Consumption Caffeine's Effect on Miscarriages 3 2 ✔ ✔ 1 ✖ Bech et al. Cnattingi us et al. Armstro ng et al. Mills et al. Percent of Miscarriages 30 Percent of Miscarriages Adjusted Odds Ratio Figure 2. These graphs show how different amounts of caffeine intake during pregnancy affect birth weight. It is clear there are conflicting conclusions on whether caffeine has an adverse effect on birth weight. A check indicates that the study found that caffeine has an effect on birth weight. An X indicates that the study found that caffeine does not have an effect on birth weight. Doses of caffeine varied between studies, but typically a low dose was around 0-150 mg, a medium dose was around 150-300 mg, and a high dose was around 300+ mg of caffeine. 10 Mills… 0 0 0 Caffeine Consumption ✖ 20 1 to 100 to 200 to 300+ 199 199 299 Caffeine Consumption (mg) Figure 3. These graphs show the effects of caffeine consumption on miscarriages. It is clear that data is conflicting. In these graphs 2 studies found that there was an effect (indicated by a check) and 2 studies found no effect (indicated by an X). Doses of caffeine varied between studies, but typically a low dose was around 0-150 mg, a medium dose was around 150-300 mg, and a high dose was around 300+ mg of caffeine. Mills et al. was kept in milligrams because the ranges of caffeine used were different than other studies. 14 Coffee Coffee Coffee (Brewed) (Boiled) (Instant) Tea Soda Cocoa Chocolate Meds Clausson et al. Mills et al. Howard et al. Armstrong et al. Bech et al. Cnattingius et al. Fenester et al. Vlajinac et al. Vik et al. Figure 4. This table shows the types of caffeine that each study monitored. Studies were grouped into those that found that caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or low birth weight (in red) and those that found it has an effect on miscarriage or low birth weight (in green). An “X” and shaded in box indicates that the study monitored that type of caffeine. Estimation of Caffeine (mg) Estimation of Caffeine in Multiple Forms 140 120 No Effect Claussen et al. 100 80 Mills et al. 60 Cnattingius et al. 40 Fenester et al. 20 Vlajinac et al. 0 Coffee (brewed) tea soda Cocoa Effect Vik et al. Form of Caffeine Figure 5. This graph shows how various studies converted types of caffeine into milligrams (mg). The brackets on the right indicate the conclusions the studies reached. Studies estimated milligrams of caffeine differently among various forms. 15 Birth Weight Study Caffeine intake does not increase the risk of low birth weight Clausson et al. Prospective Fenster et al. Vlajinac et al. Vik et al. Mills et al. Prospective Total Prospective:Retrospective 2:0 Miscarriage Study Bech et al. Cnattingius et al. Howard Armstrong et al. Mills et al. Total Prospective:Retrospective Caffeine intake does not increase the risk of low miscarriage Caffeine intake does increase the risk of low birth weight Retrospective Retrospective Retrospective 0:3 Caffeine intake does increase the risk of low miscarriage Prospective Retrospective Prospective Retrospective Prospective 2:1 1:2 Figure 6. This figure shows the two types of research designs used in the different studies. Prospective design is more reliable and accurate than retrospective design. The studies that concluded caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight used the prospective design more than the studies that concluded caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight. 16 Caffeine NO EFFECT = 5000 people Total=135,566 HAS EFFECT = 5000 people Total=93,836 Figure 7. This is a graphical explanation of Figure 8 and shows the total number of people used in the studies that found caffeine does not have an effect on miscarriages or birth weight (on the left), and the studies that found that caffeine has an effect on miscarriages or birth weight (on the right). 17 Study Clausson et al. Fenster et al. Vlajinac et al. Vik et al. Mills et al. Bech et al. Cnattingius et al. Howard et al. Armstrong et al. Mills et al. Total # of People Caffeine intake DOES NOT INCREASE the risk of miscarriages or low birth weight 953 Caffeine intake DOES INCREASE the risk of miscarriages or low birth weight 2470 1011 358 431 88,482 1,515 97,903 35,848 431 135,566 93,836 Figure 8. This table shows the number of people in the individual studies and the number of people in the combined studies based off conclusion. 18 19