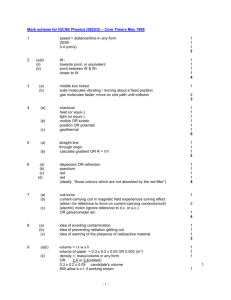

Document

advertisement

KOMPENDIUM

KAJIAN LINGKUNGAN DAN

PEMBANGUNAN

PHYTO-REMEDIATION

Hg

Dikoleksi oleh:

Novie A.S. dan Soemarno

PDKLP-PPSUB Mei 2012

FITOREMEDIASI

Phytoremediation (from Ancient Greek φυτο (phyto), meaning "plant",

and Latin remedium, meaning "restoring balance") describes the

treatment of environmental problems (bioremediation) through the use

of plants that mitigate the environmental problem without the need to

excavate the contaminant material and dispose of it elsewhere.

Phytoremediation consists of mitigating pollutant concentrations in

contaminated soils, water, or air, with plants able to contain, degrade, or

eliminate metals, pesticides, solvents, explosives, crude oil and its

derivatives, and various other contaminants from the media that contain

them.

Application

Phytoremediation may be applied wherever the soil or static water environment has become

polluted or is suffering ongoing chronic pollution. Examples where phytoremediation has

been used successfully include the restoration of abandoned metal-mine workings, reducing

the impact of sites where polychlorinated biphenyls have been dumped during manufacture

and mitigation of on-going coal mine discharges.

Phytoremediation refers to the natural ability of certain plants called hyperaccumulators to

bioaccumulate, degrade,or render harmless contaminants in soils, water, or air.

Contaminants such as metals, pesticides, solvents, explosives, and crude oil and its

derivatives, have been mitigated in phytoremediation projects worldwide. Many plants such

as mustard plants, alpine pennycress, hemp, and pigweed have proven to be successful at

hyperaccumulating contaminants at toxic waste sites.

Phytoremediation is considered a clean, cost-effective and non-environmentally disruptive

technology, as opposed to mechanical cleanup methods such as soil excavation or pumping

polluted groundwater. Over the past 20 years, this technology has become increasingly

popular and has been employed at sites with soils contaminated with lead, uranium, and

arsenic. However, one major disadvantage of phytoremediation is that it requires a long-term

commitment, as the process is dependent on plant growth, tolerance to toxicity, and

bioaccumulation capacity.

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phytoremediation …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

KEUNTUNGAN DAN KETERBATASAN

FITOREMEDIASI

KEUNTUNGAN

1.

2.

3.

4.

the cost of the phytoremediation is lower than that of traditional processes

both in situ and ex situ

the plants can be easily monitored

the possibility of the recovery and re-use of valuable metals (by companies

specializing in “phyto mining”)

it is potentially the least harmful method because it uses naturally occurring

organisms and preserves the environment in a more natural state.

KETERBATASAN

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Phytoremediation is limited to the surface area and depth occupied by the

roots.

Slow growth and low biomass require a long-term commitment with plantbased systems of remediation,

It is not possible to completely prevent the leaching of contaminants into

the groundwater (without the complete removal of the contaminated

ground, which in itself does not resolve the problem of contamination)

The survival of the plants is affected by the toxicity of the contaminated

land and the general condition of the soil.

Bio-accumulation of contaminants, especially metals, into the plants which

then pass into the food chain, from primary level consumers upwards or

requires the safe disposal of the affected plant material.

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

BERBAGAI PROSES FITOREMEDIASI

A range of processes mediated by plants or algae are useful in treating environmental

problems:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Phytoextraction — uptake and concentration of substances from the environment

into the plant biomass.

Phytostabilization — reducing the mobility of substances in the environment, for

example, by limiting the leaching of substances from the soil.

Phytotransformation — chemical modification of environmental substances as a

direct result of plant metabolism, often resulting in their inactivation, degradation

(phytodegradation), or immobilization (phytostabilization).

Phytostimulation — enhancement of soil microbial activity for the degradation of

contaminants, typically by organisms that associate with roots. This process is also

known as rhizosphere degradation. Phytostimulation can also involve aquatic

plants supporting active populations of microbial degraders, as in the stimulation

of atrazine degradation by hornwort.

Phytovolatilization — removal of substances from soil or water with release into

the air, sometimes as a result of phytotransformation to more volatile and/or less

polluting substances.

Rhizofiltration — filtering water through a mass of roots to remove toxic

substances or excess nutrients. The pollutants remain absorbed in or adsorbed to

the roots.

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

. Phytoextraction

Phytoextraction (or phytoaccumulation) uses plants or algae to remove contaminants

from soils, sediments or water into harvestable plant biomass (organisms that take

larger-than-normal amounts of contaminants from the soil are called

hyperaccumulators). Phytoextraction has been growing rapidly in popularity

worldwide for the last twenty years or so. In general, this process has been tried more

often for extracting heavy metals than for organics. At the time of disposal,

contaminants are typically concentrated in the much smaller volume of the plant

matter than in the initially contaminated soil or sediment. 'Mining with plants', or

phytomining, is also being experimented with.

The plants absorb contaminants through the root system and store them in the root

biomass and/or transport them up into the stems and/or leaves. A living plant may

continue to absorb contaminants until it is harvested. After harvest, a lower level of

the contaminant will remain in the soil, so the growth/harvest cycle must usually be

repeated through several crops to achieve a significant cleanup. After the process, the

cleaned soil can support other vegetation.

Advantages: The main advantage of phytoextraction is environmental friendliness.

Traditional methods that are used for cleaning up heavy metal-contaminated soil

disrupt soil structure and reduce soil productivity, whereas phytoextraction can clean

up the soil without causing any kind of harm to soil quality. Another benefit of

phytoextraction is that it is less expensive than any other clean-up process.

Disadvantages: As this process is controlled by plants, it takes more time than

anthropogenic soil clean-up methods.

Two versions of phytoextraction:

natural hyper-accumulation, where plants naturally take up the contaminants in soil

unassisted, and

induced or assisted hyper-accumulation, in which a conditioning fluid containing a

chelator or another agent is added to soil to increase metal solubility or mobilization

so that the plants can absorb them more easily. In many cases natural

hyperaccumulators are metallophyte plants that can tolerate and incorporate high

levels of toxic metals.

Examples of phytoextraction (see also 'Table of hyperaccumulators'):

Arsenic, using the Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), or the Chinese Brake fern (Pteris

vittata), a hyperaccumulator. Chinese Brake fern stores arsenic in its leaves.

Cadmium, using Willow (Salix viminalis): In 1999, one research experiment performed

by Maria Greger and Tommy Landberg suggested Willow (Salix viminlais) has a

significant potential as a phytoextractor of Cadmium (Cd), Zinc (Zn), and Copper (Cu),

as willow has some specific characteristics like high transport capacity of heavy metals

Sumber:of ….

Diunduhproduction;

7/5/2012 can be used also for

from root to shoot and huge amount

biomass

. Phytostabilization

Phytostabilization focuses on long-term stabilization and containment of the

pollutant. Example, the plant's presence can reduce wind erosion; or the

plant's roots can prevent water erosion, immobilize the pollutants by

adsorption or accumulation, and provide a zone around the roots where the

pollutant can precipitate and stabilize. Unlike phytoextraction,

phytostabilization focuses mainly on sequestering pollutants in soil near the

roots but not in plant tissues. Pollutants become less bioavailable, and

livestock, wildlife, and human exposure is reduced. An example application

of this sort is using a vegetative cap to stabilize and contain mine tailings

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

. Phytotransformation

In the case of organic pollutants, such as pesticides, explosives, solvents, industrial

chemicals, and other xenobiotic substances, certain plants, such as Cannas, render

these substances non-toxic by their metabolism. In other cases, microorganisms living

in association with plant roots may metabolize these substances in soil or water. These

complex and recalcitrant compounds cannot be broken down to basic molecules

(water, carbon-dioxide, etc.) by plant molecules, and, hence, the term

phytotransformation represents a change in chemical structure without complete

breakdown of the compound. The term "Green Liver Model" is used to describe

phytotransformation, as plants behave analogously to the human liver when dealing

with these xenobiotic compounds (foreign compound/pollutant).[7] After uptake of the

xenobiotics, plant enzymes increase the polarity of the xenobiotics by adding

functional groups such as hydroxyl groups (-OH).

This is known as Phase I metabolism, similar to the way that the human liver increases

the polarity of drugs and foreign compounds (Drug Metabolism). Whereas in the

human liver enzymes such as Cytochrome P450s are responsible for the initial

reactions, in plants enzymes such as nitroreductases carry out the same role.

In the second stage of phytotransformation, known as Phase II metabolism, plant

biomolecules such as glucose and amino acids are added to the polarized xenobiotic to

further increase the polarity (known as conjugation). This is again similar to the

processes occurring in the human liver where glucuronidation (addition of glucose

molecules by the UGT (e.g. UGT1A1) class of enzymes) and glutathione addition

reactions occur on reactive centres of the xenobiotic.

Phase I and II reactions serve to increase the polarity and reduce the toxicity of the

compounds, although many exceptions to the rule are seen. The increased polarity

also allows for easy transport of the xenobiotic along aqueous channels.

In the final stage of phytotransformation (Phase III metabolism), a

sequestration[disambiguation needed ] of the xenobiotic occurs within the plant. The

xenobiotics polymerize in a lignin-like manner and develop a complex structure that is

sequestered in the plant. This ensures that the xenobiotic is safely stored, and does

not affect the functioning of the plant. However, preliminary studies have shown that

these plants can be toxic to small animals (such as snails), and, hence, plants involved

in phytotransformation may need to be maintained in a closed enclosure.

Hence, the plants reduce toxicity (with exceptions) and sequester the xenobiotics in

phytotransformation. Trinitrotoluene phytotransformation has been extensively

researched and a transformation pathway has been proposed

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

. Hyperaccumulators and biotic interactions

A plant is said to be a hyperaccumulator if it can concentrate the pollutants in a

minimum percentage which varies according to the pollutant involved (for example:

more than 1000 mg/kg of dry weight for nickel, copper, cobalt, chromium or lead; or

more than 10,000 mg/kg for zinc or manganese).[10] This capacity for accumulation is

due to hypertolerance, or phytotolerance: the result of adaptative evolution from the

plants to hostile environments through many generations. A number of interactions

may be affected by metal hyperaccumulation, including protection, interferences with

neighbour plants of different species, mutualism (including mycorrhizae, pollen and

seed dispersal), commensalism, and biofilm.

Hyperaccumulators and contaminants : Al, Ag, As, Be, Cr, Cu, Mn, Hg, Mo, naphthalene, Pb, Pd, Pt, Se,

Zn – accumulation rates.

Contaminant

Accumulation

rates (in mg/kg Latin name

dry weight)

Al-Aluminium

A-

Agrostis

castellana

Hg-Mercury

A-

Bacopa monnieri

Hg-Mercury

xxx

Brassica napus

Hg-Mercury

xxx

Eichhornia

crassipes

Hg-Mercury

H-

Hydrilla verticillata

Hg-Mercury

1000

Pistia stratiotes

Hg-Mercury

xxx

Salix spp.

English name

HHyperaccumul

ator or ANotes

Accumulator PPrecipitator TTolerant

Sources

Highland Bent

Grass

As(A), Mn(A),

Pb(A), Zn(A)

[1]

Origin

Portugal.

Origin India.

Cd(H), Cr(H),

Aquatic emergent

Cu(H), Hg(A), Pb(A)

species.

Rapeseed plant Ag, Cr, Pb, Se, Zn Phytoextraction

Cd(H), Cr(A),

Pantropical/Subtro

Cu(A), Pb(H),

pical, 'the

Water Hyacinth

Zn(A)Also Cs, Sr,

troublesome

[21]

U, and

weed'.

pesticides.[22]

Hydrilla

Cd(H), Cr(A), Pb(H)

xxx

35 records of

Water lettuce

Cd(T), Cr(H), Cu(T)

plants

Ag, Cr, Se,

Petroleum

hydrocarbures,

Organic solvents,

Phytoextraction.

MTBE, TCE and byPerchlorate

[7]

Osier spp.

products; Cd, Pb,

(wetland

U, Zn (S.

halophytes)

viminalix);[8]

Potassium

ferrocyanide (S.

babylonica L.)[9]

Smooth Water

Hyssop

[1][17]

[6][7]

[1]

[1]

[1][3][31][36]

[7]

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phytoremediation,_Hyperaccumulators …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

. Phytoscreening

As plants are able to translocate and accumulate particular types of contaminants,

plants can be used as biosensors of subsurface contamination, thereby allowing

investigators to quickly delineate contaminant plumes.[11][12] Chlorinated solvents, such

as trichloroethylene, have been observed in tree trunks at concentrations related to

groundwater concentrations.[13] To ease field implementation of phytoscreening,

standard methods have been developed to extract a section of the tree trunk for later

laboratory analysis, often by using an increment borer.[14] Phytoscreening may lead to

more optimized site investigations and reduce contaminated site cleanup costs.

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phytoremediation …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Phytoremediation plants

Phytoremediation process and principles diagram. (French)

Plants used for Phytoremediation in sustainable bioremediation

treatment—cleanup—restoration projects to contain, degrade, or eliminate

transient pollution—waste and/or on-site pollution—toxins

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Rhizofiltration

Rhizofiltration is a form of bioremediation that involves filtering water through a mass

of roots to remove toxic substances or excess nutrients.

Rhizofiltration is a type of phytoremediation, which refers to the approach of using

hydroponically cultivated plant roots to remediate contaminated water through

absorption, concentration, and precipitation of pollutants.It also filters through water

and dirt.

The contaminated water is either collected from a waste site and brought to the

plants, or the plants are planted in the contaminated area, where the roots then take

up the water and the contaminants dissolved in it. Many plant species naturally uptake

heavy metals and excess nutrients for a variety of reasons: sequestration, drought

resistance, disposal by leaf abscission, interference with other plants, and defense

against pathogens and herbivores.[1] Some of these species are better than others and

can accumulate extraordinary amounts of these contaminants. Identification of such

plant species has led environmental researchers to realize the potential for using these

plants for remediation of contaminated soil and wastewater.

. Process

This process is very similar to phytoextraction in that it removes contaminants by

trapping them into harvestable plant biomass. Both phytoextraction and rhizofiltration

follow the same basic path to remediation. First, plants are put in contact with the

contamination. They absorb contaminants through their root systems and store them

in root biomass and/or transport them up into the stems and/or leaves. The plants

continue to absorb contaminants until they are harvested. The plants are then

replaced to continue the growth/harvest cycle until satisfactory levels of contaminant

are achieved. Both processes are also aimed more toward concentrating and

precipitating heavy metals than organic contaminants. The major difference between

rhizofiltration and phytoextraction is that rhizofiltration is used for treatment in

aquatic environments, while phytoextraction deals with soil remediation.

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizofiltration …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

RHIZOFILTRASI

. Applications

Weeping Willows

Rhizofiltration may be applicable to the treatment of surface water and groundwater,

industrial and residential effluents, downwashes from power lines, storm waters, acid

mine drainage, agricultural runoffs, diluted sludges, and radionuclide-contaminated

solutions. Plants suitable for rhizofiltration applications can efficiently remove toxic

metals from a solution using rapid-growth root systems. Various terrestrial plant

species have been found to effectively remove toxic metals such as Cu2+, Cd2+, Cr6+,

Ni2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+ from aqueous solutions.[2] It was also found that low level

radioactive contaminants can successfully be removed from liquid streams.[3] A system

to achieve this can consist of a “feeder layer” of soil suspended above a contaminated

stream through which plants grow, extending the bulk of their roots into the water. The

feeder layer allows the plants to receive fertilizer without contaminating the stream,

while simultaneously removing heavy metals from the water. [4] Trees have also been

applied to remediation. Trees are the lowest cost plant type. They can grow on land of

marginal quality and have long life-spans. This results in little or no maintenance costs.

The most commonly used are willows and poplars, which can grow 6 - 8’ per year and

have a high flood tolerance. For deep contamination, hybrid poplars with roots

extending 30 feet deep have been used. Their roots penetrate microscopic scale pores

in the soil matrix and can cycle 100 L of water per day per tree. These trees act almost

like a pump and treat remediation system.[5]

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizofiltration …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

RHIZOFILTRASI

. Cost

Sunflowers used for rhizofiltration

Rhizofiltration is cost-effective for large volumes of water having low concentrations of

contaminants that are subjected to stringent standards.[6] It is relatively inexpensive,

yet potentially more effective than comparable technologies. The removal of

radionuclides from water using sunflowers was estimated to cost between $2 and $6

per thousand gallons of water treated, including waste disposal and capital costs.[7]

[edit] Advantages

Rhizofiltration is a treatment method that may be conducted in situ, with plants being

grown directly in the contaminated water body. This allows for a relatively inexpensive

procedure with low capital costs. Operation costs are also low but depend on the type

of contaminant. This treatment method is also aesthetically pleasing and results in a

decrease of water infiltration and leaching of contaminants.[5] After harvesting, the

crop may be converted to biofuel briquette, a substitute for fossil fuel.[8]

[edit] Disadvantages

This treatment method has its limits. Any contaminant that is below the rooting depth

will not be extracted. The plants used may not be able to grow in highly contaminated

areas. Most importantly, it can take years to reach regulatory levels. This results in

long-term maintenance. Also, most contaminated sites are polluted with many

different kinds of contaminants. There can be a combination of metals and organics, in

which treatment through rhizofiltration will not suffice.[5] Plants grown on polluted

water and soils become a potential threat to human and animal health, and therefore,

careful attention must be paid to the harvesting process and only non-fodder crop

should be chosen for the rhizofiltration remediation method.

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

BIO-RETENSI

. Bioretention is the process in which contaminants and sedimentation are removed

from stormwater runoff. Stormwater is collected into the treatment area which

consists of a grass buffer strip, sand bed, ponding area, organic layer or mulch layer,

planting soil, and plants. Runoff passes first over or through a sand bed, which slows

the runoff's velocity, distributes it evenly along the length of the ponding area, which

consists of a surface organic layer and/or groundcover and the underlying planting soil.

The ponding area is graded, its center depressed. Water is ponded to a depth of 15 cm

(5.9 in) and gradually infiltrates the bioretention area or is evapotranspired. The

bioretention area is graded to divert excess runoff away from itself. Stored water in the

bioretention area planting soil exfiltrates over a period of days into the underlying soils

A bioretention cell, also called a rain garden, in the United States. It is designed to treat

polluted stormwater runoff from an adjacent parking lot. Plants are in winter

dormancy.

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioretention …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

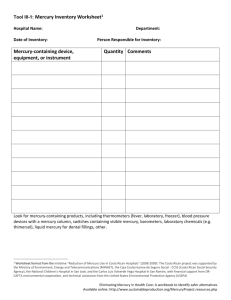

Merkuri (Hg)

. Toxicity and safety

See also: Mercury poisoning and Mercury cycle

Mercury and most of its compounds are extremely toxic and must be

handled with care; in cases of spills involving mercury (such as from certain

thermometers or fluorescent light bulbs), specific cleaning procedures are

used to avoid exposure and contain the spill.[77] Protocols call for physically

merging smaller droplets on hard surfaces, combining them into a single

larger pool for easier removal with an eyedropper, or for gently pushing the

spill into a disposable container. Vacuum cleaners and brooms cause greater

dispersal of the mercury and should not be used. Afterwards, fine sulfur,

zinc, or some other powder that readily forms an amalgam (alloy) with

mercury at ordinary temperatures is sprinkled over the area before itself

being collected and properly disposed of. Cleaning porous surfaces and

clothing is not effective at removing all traces of mercury and it is therefore

advised to discard these kinds of items should they be exposed to a mercury

spill.

Mercury can be inhaled and absorbed through the skin and mucous

membranes, so containers of mercury are securely sealed to avoid spills and

evaporation. Heating of mercury, or of compounds of mercury that may

decompose when heated, is always carried out with adequate ventilation in

order to avoid exposure to mercury vapor. The most toxic forms of mercury

are its organic compounds, such as dimethylmercury and methylmercury.

Inorganic compounds, such as cinnabar are also highly toxic by ingestion or

inhalation.[78] Mercury can cause both chronic and acute poisoning.

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_%28element%29 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Merkuri (Hg):

Pelepasan ke Lingkungan

. Preindustrial deposition rates of mercury from the atmosphere may be about 4 ng /(1

L of ice deposit). Although that can be considered a natural level of exposure, regional

or global sources have significant effects. Volcanic eruptions can increase the

atmospheric source by 4–6 times.[79]

Natural sources, such as volcanoes, are responsible for approximately half of

atmospheric mercury emissions. The human-generated half can be divided into the

following estimated percentages:[80][81][82]

65% from stationary combustion, of which coal-fired power plants are the largest

aggregate source (40% of U.S. mercury emissions in 1999). This includes power plants

fueled with gas where the mercury has not been removed. Emissions from coal

combustion are between one and two orders of magnitude higher than emissions from

oil combustion, depending on the country.[80]

11% from gold production. The three largest point sources for mercury emissions in

the U.S. are the three largest gold mines. Hydrogeochemical release of mercury from

gold-mine tailings has been accounted as a significant source of atmospheric mercury

in eastern Canada.[83]

6.8% from non-ferrous metal production, typically smelters.

6.4% from cement production.

3.0% from waste disposal, including municipal and hazardous waste, crematoria, and

sewage sludge incineration.

3.0% from caustic soda production.

1.4% from pig iron and steel production.

1.1% from mercury production, mainly for batteries.

2.0% from other sources.

The above percentages are estimates of the global human-caused mercury emissions

in 2000, excluding biomass burning, an important source in some regions.[80]

Current atmospheric mercury contamination in outdoor urban air is (0.01–0.02 µg/m3)

indoor concentrations are significantly elevated over outdoor concentrations, in the

range 0.0065–0.523 µg/m3 (average 0.069 µg/m3).[84]

Mercury also enters into the environment through the improper disposal (e.g., land

filling, incineration) of certain products. Products containing mercury include: auto

parts, batteries, fluorescent bulbs, medical products, thermometers, and

thermostats.[85] Due to health concerns (see below), toxics use reduction efforts are

cutting back or eliminating mercury in such products. For example, the amount of

mercury sold in thermostats in the United States decreased from 14.5 tons in 2004 to

3.9 tons in 2007.[86] Most thermometers now use pigmented alcohol instead of

mercury, and galinstan alloy thermometers are also an option. Mercury thermometers

are Sumber:

still occasionally

used in the medical field because they are

more accurate

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_%28element%29

…. Diunduh

7/5/2012 than

Merkuri (Hg)

. Chemistry

See also: Category:Mercury compounds

Mercury exists in two main oxidation states, I and II. Higher oxidation states are

unimportant, but have been detected, e.g., mercury(IV) fluoride (HgF4) but only under

extraordinary conditions.[29]

[edit] Compounds of mercury(I)

Different from its lighter neighbors, cadmium and zinc, mercury forms simple stable

compounds with metal-metal bonds. The mercury(I) compounds are diamagnetic and

feature the dimeric cation, Hg2+

2. Stable derivatives include the chloride and nitrate. Treatment of Hg(I) compounds

complexation with strong ligands such as sulfide, cyanide, etc. induces

disproportionation to Hg2+ and elemental mercury.[30] Mercury(I) chloride, a colorless

solid also known as calomel, is really the compound with the formula Hg2Cl2, with the

connectivity Cl-Hg-Hg-Cl. It is a standard in electrochemistry. It reacts with chlorine to

give mercuric chloride, which resists further oxidation.

Indicative of its tendency to bond to itself, mercury forms mercury polycations, which

consist of linear chains of mercury centers, capped with a positive charge. One

example is Hg32+(AsF6–)2.[31]

[edit] Compounds of mercury(II)

Mercury(II) is the most common oxidation state and is the main one in nature as well.

All four mercuric halides are known. The form tetrahedral complexes with other

ligands but the halides adopt linear coordination geometry, somewhat like Ag+ does.

Best known is mercury(II) chloride, an easily sublimating white solid. HgCl2 forms

coordination complexes that are typically tetrahedral, e.g. HgCl42–.

Mercury(II) oxide, the main oxide of mercury, arises when the metal is exposed to air

for long periods at elevated temperatures. It reverts to the elements upon heating

near 400 °C, as was demonstrated by Priestly in an early synthesis of pure oxygen.[7]

Hydroxides of mercury are poorly characterized, as they are for its neighbors gold and

silver.

Being a soft metal, mercury forms very stable derivatives with the heavier chalcogens.

Preeminent is mercury(II) sulfide, HgS, which occurs in nature as the ore cinnabar and

is the brilliant pigment vermillion. Like ZnS, HgS crystallizes in two forms, the reddish

cubic form and the black zinc blende form.[5] Mercury(II) selenide (HgSe) and

mercury(II) telluride (HgTe) are also known, these as well as various derivatives, e.g.

mercury cadmium telluride and mercury zinc telluride being semiconductors useful as

infrared detector materials.[32]

Mercury(II) salts form a variety of complex derivatives with ammonia. These include

+

Millon's

basehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_%28element%29

(Hg2N+), the one-dimensional polymer (salts of….

HgNH

and "fusible

Sumber:

Diunduh

7/5/2012

2 )n),

Merkuri (Hg)

. Properties

[edit] Physical properties

A pound coin (density ~7.6 g/cm3) floats in mercury due to the combination of the

buoyant force and surface tension.

Mercury is a heavy, silvery-white metal. As compared to other metals, it is a poor

conductor of heat, but a fair conductor of electricity.[5] Mercury has an exceptionally

low melting temperature for a d-block metal. A complete explanation of this fact

requires a deep excursion into quantum physics, but it can be summarized as follows:

mercury has a unique electronic configuration where electrons fill up all the available

1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 3d, 4s, 4p, 4d, 4f, 5s, 5p, 5d and 6s subshells. As such configuration

strongly resists removal of an electron, mercury behaves similarly to noble gas

elements, which form weak bonds and thus easily melting solids. The stability of the 6s

shell is due to the presence of a filled 4f shell. An f shell poorly screens the nuclear

charge that increases the attractive Coulomb interaction of the 6s shell and the

nucleus (see lanthanide contraction). The absence of a filled inner f shell is the reason

for the somewhat higher melting temperature of cadmium and zinc, although both

these metals still melt easily and, in addition, have unusually low boiling points. Metals

such as gold have atoms with one less 6s electron than mercury. Those electrons are

more easily removed and are shared between the gold atoms forming relatively strong

metallic bonds.[3][6]

[edit] Chemical properties

Mercury does not react with most acids, such as dilute sulfuric acid, although oxidizing

acids such as concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid or aqua regia dissolve it to give

sulfate, nitrate, and chloride salts. Like silver, mercury reacts with atmospheric

hydrogen sulfide. Mercury even reacts with solid sulfur flakes, which are used in

mercury spill kits to absorb mercury vapors (spill kits also use activated carbon and

powdered zinc).[7]

Sumber: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_%28element%29 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Mercury is an element

Mercury (Hg) is a silvery metallic liquid as toom temperature. Nautral sources of Hg

occur from outgassing of the earth's crust through volcanoes and evaporation from the

ocean. It can be found in familiar items such as lightbulbs, batteries, thermometers,

pesticides, paint and some dental fillings (amalgams). It is also sometimes used as a

catalyst in chemical reactions or in gold extraction procedures. In nature, mercury

exists in several forms: 1) as ionic salts in either the mercurous (I) or mercuric (II)

states, 2) as an organometallic compound such as methyl mercury, or 3) as elemental

mercury Hg(0) in either liquid or vapor phase.

Mercury in the Environment

Mercury is believed to be transported throughout the environment by two

cycles. On a global scale, Hg(0) vapor circulates through the earth's atmosphere from

land sources to the oceans (3). Researchers believe that the global amount of Hg has

increased by a factor of 2-5 since the advent of industry (3). This amounts to a total

estimate of approximately 10,000 tons of mercury being released worldwide into the

environment from both man-made and natural sources. The second cycle occurs on a

local scale and involves methylation of atmospheric mercury, which is deposited into

bodies of water, by methanogenic bacteria to form methyl mercury. This compound is

somewhat soluble in water and is taken up by organisms and concentrations are

"biomagnified" in animals such as fish, which are higher up in the food chain (3).

Sumber: http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/homepage.html …. Diunduh

7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

. The Problem: Mercury is toxic to many organisms

Because many animals, including humans, can potentially feed on contaminated

fish, shellfish, or sea mammals, contamination poses an immediate health threat.

Mercury is toxic to humans

During the 1950's the first major mercury posioning epidemic occurred in Minamata

Bay in Kyushu, Japan. Residents had cons

umed methyl mercury-contaminated fish and shellfish. The source of contamination

was effluent from a chemical manufacturing company, Chisso, which specialized in the

production of acetylaldehyde. Mercury was used as a catalyst in the production

process and waste was released into Minamata Bay. Many families who suffered

posioning were associated with the local fishing industry. Victims experienced ataxia

(loss of precise control of movement), visual problems, loss of hearing and mental

confusion. They became prone

to shouting and violent behavior which often lead to coma (1). An estimated 1,435

people have died because of this contamination (4). Additional epidemics occurred

not long afterward in Niigata, Japan due to contaminated seafood (1) and in Iraq due

to consumption of seed grain that had been treated with a mercury-containing

fungicide (2). The largest concern, however, is that low levels of mercury exposure is

particularly harmful to the fetus. Infants born to mothers who have been exposed to

mercury contamination while or before becoming pregnant have shown a high

incidence of mental retardation, ataxia, seizure, sensory disturbance, visual problems,

and hearing impairment (1).

Sumber: http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/homepage.html …. Diunduh

7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Mercury is toxic to most plants

Plants that are exposed to mercury accumulate the metal, however

drastic decreases in growth are usually observed. Plants exposed to ionic

mercury through the root exhibit reduced growth of shoots and roots. They

also accumulate mercury in the root with slow movement to the

shoot. Tree leaves can trap atmospheric mercury. It is thought that

inorganic mercury may cause changes in root tip cell membrane integrity

while methyl mercury may affect organelle metabolism processes that

eventually interrup cell membrane integrity

Sumber: http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/homepage.html …. Diunduh

7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

. A solution: Removing methyl mercury from water and soil Phytoremediation Technologies

Phytoremediation or remedying a contaminated site using plants, is a

relatively new area of research. Mercury-resistant bacteria have been

reported to produce enzymes that catalyze two reactions: 1)

organomercurial lyase - which removes methyl groups from mercury to

create ionic mercury, and 2) mercuric ion reductase which converts ionic

mercury to volatile elemental mercury. Plants engineered to express these

genes could have potential for relatively inexpensive clean-up of mercury

contaminated sites. Additionally, many sites that are contaminated with

various metals are also contaminated with mercury which may be the most

toxic metal and is limiting to growth. Volatilization of elemental mercury

would allow mercury to diffuse out of the plant and into the atmosphere at

diffuse and non-toxic concentrations (15).

. Phytoremediation Technologies

-Solutions(sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationt

echnologies.html )

Mercury pollution poses an immediate threat not only to human health, but also to

other plants, microorganisms and animals in the environment. Methanogenic bacteria

convert ionic and/or elemental mercury to methyl mercury, which is highly

toxic. Other bacteria have been reported to produce enzymes that remove methyl

groups from mercury and reduce ionic mercury to less toxic elemental mercury Hg

(0). Elemental Hg (0) is highly volatile and is readily converted from liquid to vaporphase. These bacteria could be used to volatilize Hg (0), however this process is

slow. The genes involved in bacterial conversion of methyl mercury to ionic mercury

Hg+, to elemental mercury vapor Hg(0) are all a part of a mercury-responsive bacterial

operon. When a bacterium is exposed to mercury, the gene products of the operon

are expressed. These include a mercury responsive regulatory protein, transport

proteins that bind and transport mercury into the cell, organomercuric lyase, which

catalyzes

the removal of the methyl group of methyl mercury converting it into

ionic

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/homepage.html

…. Diunduh

mercury Hg+ (merB), and mercuric ion

reductase which catalyzes the conversion of

7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Rugh, C., Dayton Wilde, H., Stack, N., Thompson, D.M., Summers A.O., and Meagher, R.B.,

(1996) Mercuric ion reduction and resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants expressing

a modified bacterial merA gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93:3182-3187.

The enzyme, mercuric ion reductase, encoded by the gene merA, reduces ionic

mercury (Hg+) to the less toxic volatile Hg(0) using NADPH reducing

equivalents. Because the merA gene was found to be very G+C rich (~67%) and was

suited for expression only in a bacterial system, early attempts to express this gene in

plant systems were unsuccessful.

Rugh et al. replaced codons 287-336, which constituted 9% of the coding region to

contain a sequence of DNA that had codon usage that was more suited to expression

in plant systems. Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants containing this modified

merApe9 expressed the gene product mercuric ion reductase. Additionally, merApe9

seeds germinated and grew into seedlings on agar plates containing 50 micromolar

HgCl2 while control plants did not.

Mercury vapor analysis showed that transgenic merApe9 plants

volatilized significant amounts (~50 ng Hg(0)/mg tissue of mercury

vapor.

Finally, Northern blots of total mRNA from transgenic plants

confirmed merApe9 gene expression. These data suggest that the

potential for plants that volatilize Hg are viable.

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationtechnologies.html ….

Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Rugh, C., Senecoff, J., Meagher, R., and Merkle, S. (1998) Development of

transgenic yellow poplar for mercury phytoremediation. Nature

Biotechnology. 16:925-928.

. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing the merA9 gene construct converted ionic

Hg+ to volatile Hg(0). Expression of this type of system in a high biomass plant with

potential environmental application, such as yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera)

may provide a means for phytovolatilization of mercury pollution. The merA9

sequence was further modified to contain an additional 9% of the coding sequence

fragment of DNA with plant-like codon usage. This further modified merA18 sequence

was transformed using particle bombardment of yellow poplar proembryonic

masses. Transgenic plantlets grew on agar plates containing 25microM and 50microM

HgCl2, whereas control plants did not. Additionally significant Hg (0) volatilization was

observed by transgenic lines. The demonstrated ability of genetically engineered

yellow poplar to grow on increased concentrations of ionic Hg+ may demonstrate the

potential for phytovolitazion methods of mercury remediation. However, this research

is still in its infancy and future experiments may include growing transgenic poplar

plants on mercury-contaminated soils.

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationtechnologies.html ….

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Bizily, S., Rugh, C., Summers, A., Meagher, R. (1999) Phytoremediation of

methylmercury pollution: merB expression in Arabidopsis thaliana confers resistance

to organomercurials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96:6808-6813.

Mercury deposited into bodies of water is typically converted to methyl-mercury by

methanogenic bacteria. Other mercury-resistant bacteria eliminate methyl mercury by

producing an enzyme, organomercurial lyase encoded by the gene merB. Because

most mercury-contaminated water contains methyl mercury, there would be a benefit

to producing a model system in which merB was expressed.

Bizily et al., report that transformants of Arabidopsis with merB grow on higher

concentrations of methyl mercury-like compounds than control plants. The merB

gene that was isolated from mercury-resistant bacteria was modified using PCR

techniques to contain flanking regions containing consensus plant sequences and

restriction sites.

The new merB gene was transformed into Arabidopsis thaliana by Agrobacterium

tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Transgenic merB plants grew on agar

plates containing phenylmercuric acetate or methylmercuric chloride while control

plants and transgenic merA plants did not. Additional western blot studies

confirmed the expression of significant amounts of the merB gene product,

organomercruial lyase.

Results suggest that merB was successfully transformed and expressed in

Arabidopsis thaliana plants as well as conferring resistance to organomercurials.

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationtechnologies.html ….

Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Bizily, S., Rugh, C., Meagher, R. (2000) Phytodetoxification of hazardous

organomercurials by genetically engineered plants. Nature Biotechnology. 18:213217.

Methylmercury is found in wetlands and aquatic sediments worldwide. Both ionic

mercury and methylmercury are absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract of animals, but

methylmercury is retained much longer in the body and is, therefore, is carried up

through the food chain more efficiently. Plants engineered with both the merA and

merB genes should be able to extract methylmercury from contaminated

environments and transpire Hg(0) into the atmosphere.

Because Hg(0) resides in the atmosphere for approximately two years, transpired

Hg(0) will be diluted to much lower concentrations before being redeposited into

terrestrial waters and sediments rather than being concentrated in one

area. Additionally the amount of Hg(0) emitted from sites undergoing

phytovolitalization can be regulated and will most likely be small in comparison to the

concentrations of Hg(0) already in the atmosphere.

Arabidopsis thaliana plants that had been separately transformed to contain

constructs that express merA and merB, respectively, were crossed. F2

generation plants were analyzed for expression of both the merA and merB

gene products in the same plant. Plantlets containing merA or merA and

merB grew on concentrations of methylmercury-like compounds (mainly

CH3HgCl) up to 5 micromolar. Only plants expressing the gene products of

both merA and merB grew on concentrations of 10 micromolar methyl

mercury.

Mercury vapor analysis showed significant Hg(0) volatilization emitted from

merA/merB plants and western blots confirmed the expression of the gene

products of merA and merB. These results demonstrate that transgenic plants

efficiently phytovolatilize methylmercury.

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationtechnologies.html ….

Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

Wantanabe, Chiho, Satoh, Hiroshi. (1996) Evolution of our understanding of methylmercury as a

health threat. Environmental Health Perspectives Supplements. 104(2):367.

Wheeler, M. (1996) Measuring Mercury. Environmental Health Perspectives.

104(8): http://ephnet1.nih.gov/docs/1996/104-8/focus.html.

Boening, D. (2000) Ecological effectws, transport, and fate of mercury: a general

review. Chemosphere. 40:1335-1351.

Greimel, H. (2001) Poisoning victims of Japan's mercury bay may be double previous

estimates. http://www.enn.com/news/wire-stories/2001/10112001/ap-45234.asp

Mercury Chemical Backgrounder. http://www.nsc.org/library/chemical/Mercury.htm

Mercury, chemical element: The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth

Edition. (2001). http://www.bartelby.com/65/me/mercury/html

Chemical Properties of Mercury. http://pasture.ecn.purdue.edu/~mercury/src/props.htm

Toxic Mercury Rains on U.S. Midwest. (1999) http://www.uwsp.edu/geo/courses/geog100/ENSMercury.htm

UGA Genetics - Richard B. Meagher. http://www.genetics.uga.edu/faculty/bio-Meagher.html

Phytoremediation Research Lab, Michigan State University. Department of Crop and Soil

Sciences. http://www.css.msu.edu/phytoremediation/c_rugh.html

Applied PhytoGenetics Inc. Apgen's phytoremediation technologies. http://www.applied

phytogenetics.com/apgen/technology.htm

Rugh, C., Wilde, H.D., Stack, N., Thompson, D., Summers, A., and Meagher, R. (1996) Mercuric

ion reduction and resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants expressing a modified

bacterial merA gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93:3182-3187.

Rugh, C., Senecoff, J., Meagher, R., and Merkle, S. (1998) Development of transgenic yellow

poplar for mercury phytoremediation. Nature Biotechnology. 16:925-928.

Bizily, S., Rugh, C., Summers, A., and Meagher, R. (1999) Phytoremediation of methylmercury

pollution: merB expression in Arabidopsis thaliana confers resistance to organomercurials. Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci. 96:6808-6813.

Bizily, S., Rugh, C., Meagher, R. (2000) Phytodetoxification of hazardous organomercurials by

genetically engineered plants. Nature Biotechnology. 18:213-217.

Sumber:

http://rydberg.biology.colostate.edu/Phytoremediation/2003/Amy/phytoremediationtechnologies.html ….

Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

. Phytoremediation of Mercury and Organomercurials in Chloroplast Transgenic Plants:

Enhanced Root Uptake, Translocation to Shoots, and Volatilization

Hussein S. Hussein,† Oscar N. Ruiz,‡§ Norman Terry,† and Henry Daniell

Environ Sci Technol. 2007 December 15; 41(24): 8439–8446.

. Transgenic tobacco plants engineered with bacterial merA and merB genes via the

chloroplast genome were investigated to study the uptake, translocation of different

forms of mercury (Hg) from roots to shoots, and their volatilization. Untransformed

plants, regardless of the form of Hg supplied, reached a saturation point at 200 µM of

phenylmercuric acetate (PMA) or HgCl2, accumulating Hg concentrations up to 500 µg

g−1 with significant reduction in growth. In contrast, chloroplast transgenic lines

continued to grow well with Hg concentrations in root tissues up to 2000 µg g−1.

Chloroplast transgenic lines accumulated both the organic and inorganic Hg forms to

levels surpassing the concentrations found in the soil. The organic-Hg form was

absorbed and translocated more efficiently than the inorganic-Hg form in transgenic

lines, whereas no such difference was observed in untransformed plants. Chloroplasttransgenic lines showed about 100-fold increase in the efficiency of Hg accumulation in

shoots compared to untransformed plants. This is the first report of such high levels of

Hg accumulation in green leaves or tissues. Transgenic plants attained a maximum rate

of elemental-Hg volatilization in two days when supplied with PMA and in three days

when supplied with inorganic-Hg, attaining complete volatilization within a week. The

combined expression of merAB via the chloroplast genome enhanced conversion of

Hg2+ into Hg,0 conferred tolerance by rapid volatilization and increased uptake of

different forms of mercury, surpassing the concentrations found in the soil. These

investigations provide novel insights for improvement of plant tolerance and

detoxification of mercury.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2590779/…. Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

Differential mercury volatilization by tobacco organs expressing a

modified bacterial merA gene.

He YK, Sun JG, Feng XZ, Czakó M, Márton L.

Cell Res. 2001 Sep;11(3):231-6.

. Mercury pollution is a major environmental problem accompanying industrial

activities. Most of the mercury released ends up and retained in the soil as complexes

of the toxic ionic mercury (Hg2+), which then can be converted by microbes into the

even more toxic methylmercury which tends to bioaccumulate. Mercury detoxification

of the soil can also occur by microbes converting the ionic mercury into the least toxic

metallic mercury (Hg0) form, which then evaporates. The remediation potential of

transgenic plants carrying the MerA gene from E. coli encoding mercuric ion reductase

could be evaluated. A modified version of the gene, optimized for plant codon

preferences (merApe9, Rugh et al. 1996), was introduced into tobacco by

Agrobacterium-mediated leaf disk transformation. Transgenic seeds were resistant to

HgCl2 at 50 microM, and some of them (10-20% ) could germinate on media containing

as much as 350 microM HgCl2, while the control plants were fully inhibited or died on

50 microM HgCl2. The rate of elemental mercury evolution from Hg2+ (added as

HgCl2) was 5-8 times higher for transgenic plants than the control. Mercury

volatilization by isolated organs standardized for fresh weight was higher (up to 5

times) in the roots than in shoots or the leaves. The data suggest that it is the root

system of the transgenic plants that volatilizes most of the reduced mercury (Hg0). It

also suggests that much of the mercury need not enter the vascular system to be

transported to the leaves for volatilization. Transgenic plants with the merApe9 gene

may be used to mercury detoxification for environmental improvement in mercurycontaminated regions more efficiently than it had been predicted based on data on

volatilization of whole plants via the upper parts only (Rugh et al. 1996).

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11642409…. Diunduh 7/5/2012

FITOREMEDIASI Merkuri (Hg)

. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011 Jun;9(5):609-17. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00616.x.

Epub 2011 Apr 24.

Metallothionein expression in chloroplasts enhances mercury accumulation and

phytoremediation capability.

Ruiz ON, Alvarez D, Torres C, Roman L, Daniell H.

. Genetic engineering to enhance mercury phytoremediation has been accomplished

by expression of the merAB genes that protects the cell by converting Hg[II] into Hg[0]

which volatilizes from the cell. A drawback of this approach is that toxic Hg is released

back into the environment. A better phytoremediation strategy would be to

accumulate mercury inside plants for subsequent retrieval. We report here the

development of a transplastomic approach to express the mouse metallothionein gene

(mt1) and accumulate mercury in high concentrations within plant cells. Real-time PCR

analysis showed that up to 1284 copies of the mt1 gene were found per cell when

compared with 1326 copies of the 16S rrn gene, thereby attaining homoplasmy. Past

studies in chloroplast transformation used qualitative Southern blots to evaluate

indirectly transgene copy number, whereas we used real-time PCR for the first time to

establish homoplasmy and estimate transgene copy number and transcript levels. The

mt1 transcript levels were very high with 183,000 copies per ng of RNA or 41% the

abundance of the 16S rrn transcripts. The transplastomic lines were resistant up to 20

μm mercury and maintained high chlorophyll content and biomass. Although the

transgenic plants accumulated high concentrations of mercury in all tissues, leaves

accumulated up to 106 ng, indicating active phytoremediation and translocation of

mercury. Such accumulation of mercury in plant tissues facilitates proper disposal or

recycling. This study reports, for the first time, the use of metallothioneins in plants for

mercury phytoremediation. Chloroplast genetic engineering approach is useful to

express metal-scavenging proteins for phytoremediation.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21518240…. Diunduh 7/5/2012

J. Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005 Dec;32(11-12):502-13. Epub 2005 Jul 2.

Strategies for the engineered phytoremediation of toxic element pollution: mercury and

arsenic.

Meagher RB, Heaton AC.

Plants have many natural properties that make them ideally suited to clean up polluted

soil, water, and air, in a process called phytoremediation. We are in the early stages of

testing genetic engineering-based phytoremediation strategies for elemental

pollutants like mercury and arsenic using the model plant Arabidopsis. The long-term

goal is to develop and test vigorous, field-adapted plant species that can prevent

elemental pollutants from entering the food-chain by extracting them to aboveground

tissues, where they can be managed. To achieve this goal for arsenic and mercury, and

pave the way for the remediation of other challenging elemental pollutants like lead or

radionucleides, research and development on native hyperaccumulators and

engineered model plants needs to proceed in at least eight focus areas: (1) Plant

tolerance to toxic elementals is essential if plant roots are to penetrate and extract

pollutants efficiently from heterogeneous contaminated soils. Only the roots of

mercury- and arsenic-tolerant plants efficiently contact substrates heavily

contaminated with these elements. (2) Plants alter their rhizosphere by secreting

various enzymes and small molecules, and by adjusting pH in order to enhance

extraction of both essential nutrients and toxic elements. Acidification favors greater

mobility and uptake of mercury and arsenic. (3) Short distance transport systems for

nutrients in roots and root hairs requires numerous endogenous transporters. It is

likely that root plasma membrane transporters for iron, copper, zinc, and phosphate

take up ionic mercuric ions and arsenate. (4) The electrochemical state and chemical

speciation of elemental pollutants can enhance their mobility from roots up to shoots.

Initial data suggest that elemental and ionic mercury and the oxyanion arsenate will be

the most mobile species of these two toxic elements. (5) The long-distance transport

of nutrients requires efficient xylem loading in roots, movement through the xylem up

to leaves, and efficient xylem unloading aboveground. These systems can be enhanced

for the movement of arsenic and mercury. (6) Aboveground control over the

electrochemical state and chemical speciation of elemental pollutants will maximize

their storage in leaves, stems, and vascular tissues. Our research suggests ionic Hg(II)

and arsenite will be the best chemical species to trap aboveground. (7) Chemical sinks

can increase the storage capacity for essential nutrients like iron, zinc, copper, sulfate,

Sumber: …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

and phosphate. Organic acids and thiol-rich chelators are among the important

Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2009 Mar;16(2):162-75. Epub 2008 Dec 6.

Implications of metal accumulation mechanisms to phytoremediation.

Memon AR, Schröder P.

. BACKGROUND, AIM, AND SCOPE:

Trace elements (heavy metals and metalloids) are important environmental pollutants, and many of

them are toxic even at very low concentrations. Pollution of the biosphere with trace elements has

accelerated dramatically since the Industrial Revolution. Primary sources are the burning of fossil fuels,

mining and smelting of metalliferous ores, municipal wastes, agrochemicals, and sewage. In addition,

natural mineral deposits containing particularly large quantities of heavy metals are found in many

regions. These areas often support characteristic plant species thriving in metal-enriched

environments. Whereas many species avoid the uptake of heavy metals from these soils, some of

them can accumulate significantly high concentrations of toxic metals, to levels which by far exceed

the soil levels. The natural phenomenon of heavy metal tolerance has enhanced the interest of plant

ecologists, plant physiologists, and plant biologists to investigate the physiology and genetics of metal

tolerance in specialized hyperaccumulator plants such as Arabidopsis halleri and Thlaspi caerulescens.

In this review, we describe recent advances in understanding the genetic and molecular basis of metal

tolerance in plants with special reference to transcriptomics of heavy metal accumulator plants and

the identification of functional genes implied in tolerance and detoxification.

RESULTS:

Plants are susceptible to heavy metal toxicity and respond to avoid detrimental effects in a variety of

different ways. The toxic dose depends on the type of ion, ion concentration, plant species, and stage

of plant growth. Tolerance to metals is based on multiple mechanisms such as cell wall binding, active

transport of ions into the vacuole, and formation of complexes with organic acids or peptides. One of

the most important mechanisms for metal detoxification in plants appears to be chelation of metals by

low-molecular-weight proteins such as metallothioneins and peptide ligands, the phytochelatins. For

example, glutathione (GSH), a precursor of phytochelatin synthesis, plays a key role not only in metal

detoxification but also in protecting plant cells from other environmental stresses including intrinsic

oxidative stress reactions. In the last decade, tremendous developments in molecular biology and

success of genomics have highly encouraged studies in molecular genetics, mainly transcriptomics, to

identify functional genes implied in metal tolerance in plants, largely belonging to the metal

homeostasis network.

DISCUSSION:

Analyzing the genetics of metal accumulation in these accumulator plants has been greatly enhanced

through the wealth of tools and the resources developed for the study of the model plant Arabidopsis

thaliana such as transcript profiling platforms, protein and metabolite profiling, tools depending on

RNA interference (RNAi), and collections of insertion line mutants. To understand the genetics of metal

accumulation and adaptation, the vast arsenal of resources developed in A. thaliana could be extended

to one of its closest relatives that display the highest level of adaptation to high metal environments

such as A. halleri and T. caerulescens.

CONCLUSIONS:

This review paper deals with the mechanisms of heavy metal accumulation and tolerance in plants.

Detailed information has been provided for metal transporters, metal chelation, and oxidative stress in

metal-tolerant plants. Advances in phytoremediation technologies and the importance of metal

accumulator plants and strategies for exploring these immense and valuable genetic and biological

resources for phytoremediation are discussed.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND PERSPECTIVES:

A number of species within the Brassicaceae

have7/5/2012

been identified as metal accumulators. To

Sumber: ….family

Diunduh

understand fully the genetics of metal accumulation, the vast genetic resources developed in A.

. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2009 Mar;16(2):162-75. Epub 2008 Dec 6.

Implications of metal accumulation mechanisms to phytoremediation.

Memon AR, Schröder P.

. BACKGROUND, AIM, AND SCOPE:

Trace elements (heavy metals and metalloids) are important environmental pollutants, and many of

them are toxic even at very low concentrations. Pollution of the biosphere with trace elements has

accelerated dramatically since the Industrial Revolution. Primary sources are the burning of fossil

fuels, mining and smelting of metalliferous ores, municipal wastes, agrochemicals, and sewage. In

addition, natural mineral deposits containing particularly large quantities of heavy metals are found in

many regions. These areas often support characteristic plant species thriving in metal-enriched

environments. Whereas many species avoid the uptake of heavy metals from these soils, some of

them can accumulate significantly high concentrations of toxic metals, to levels which by far exceed

the soil levels. The natural phenomenon of heavy metal tolerance has enhanced the interest of plant

ecologists, plant physiologists, and plant biologists to investigate the physiology and genetics of metal

tolerance in specialized hyperaccumulator plants such as Arabidopsis halleri and Thlaspi caerulescens.

In this review, we describe recent advances in understanding the genetic and molecular basis of metal

tolerance in plants with special reference to transcriptomics of heavy metal accumulator plants and

the identification of functional genes implied in tolerance and detoxification.

RESULTS:

Plants are susceptible to heavy metal toxicity and respond to avoid detrimental effects in a variety of

different ways. The toxic dose depends on the type of ion, ion concentration, plant species, and stage

of plant growth. Tolerance to metals is based on multiple mechanisms such as cell wall binding, active

transport of ions into the vacuole, and formation of complexes with organic acids or peptides. One of

the most important mechanisms for metal detoxification in plants appears to be chelation of metals

by low-molecular-weight proteins such as metallothioneins and peptide ligands, the phytochelatins.

For example, glutathione (GSH), a precursor of phytochelatin synthesis, plays a key role not only in

metal detoxification but also in protecting plant cells from other environmental stresses including

intrinsic oxidative stress reactions. In the last decade, tremendous developments in molecular biology

and success of genomics have highly encouraged studies in molecular genetics, mainly

transcriptomics, to identify functional genes implied in metal tolerance in plants, largely belonging to

the metal homeostasis network.

DISCUSSION:

Analyzing the genetics of metal accumulation in these accumulator plants has been greatly enhanced

through the wealth of tools and the resources developed for the study of the model plant Arabidopsis

thaliana such as transcript profiling platforms, protein and metabolite profiling, tools depending on

RNA interference (RNAi), and collections of insertion line mutants. To understand the genetics of

metal accumulation and adaptation, the vast arsenal of resources developed in A. thaliana could be

extended to one of its closest relatives that display the highest level of adaptation to high metal

environments such as A. halleri and T. caerulescens.

CONCLUSIONS:

This review paper deals with the mechanisms of heavy metal accumulation and tolerance in plants.

Detailed information has been provided for metal transporters, metal chelation, and oxidative stress

in metal-tolerant plants. Advances in phytoremediation technologies and the importance of metal

accumulator plants and strategies for exploring these immense and valuable genetic and biological

resources for phytoremediation are discussed.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND PERSPECTIVES:

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19067014

…. Diunduh 7/5/2012.

A number of species within the Brassicaceae family have been identified as metal accumulators. To

. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 2003 Apr;14(4):632-6.

[Phytochelatin and its function in heavy metal tolerance of higher plants].

[Article in Chinese]

Wu F, Zhang G.

. The biosynthesis pathway of phytochelatins (PC) and its function in heavy metal

tolerance of higher plants were summarized in this paper. The toxic heavy metal

accumulation in soil would deteriorates crop growth and yield components, and

threaten the agro-products security. There were significantly differences in the

accumulation and tolerance to heavy metals among plant species and genotypes. The

formation of PC in response to the stress caused by heavy metals was one of the truly

adaptive responses occurred commonly in higher plants. In the heavy metal tolerant

genotypes, there was a much higher accumulation of PC than the non-tolerant lines.

Glutathione (GSH) was the substrate for the synthesis of PC, which chelated the

metals. The inactive toxic metal ions of metal--PC chelatins were subsequently

transported from cytosol to vacuole before they could poison the enzymes of lifesupporting metabolic routes, and transiently stored in vacuole to reduce the heavy

metal concentration in cytosol, thus, heavy metal detoxification was attained. The

break through of genetic mechanism and bio-chemical pathway of PC synthesis

induced by heavy metals would depend on the further study on molecular biology in

this field. The isolation of Cd-sensitive cad1 and cad2 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana,

that was deficient in PC, demonstrted the importance of PC for heavy metal tolerance.

The effect of PC on food security and on phytoremediation of soil and water

contaminated by heavy metals was also discussed in this paper.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12920919 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Gene. 1996 Nov 7;179(1):21-30.

Heavy metal detoxification in higher plants--a review.

Zenk MH.

. A set of heavy-metal-complexing peptides was isolated from plants and plant

suspension cultures. The structure of these peptides was established as (gammaglutamic acid-cysteine)n-glycine (n = 2-11) [(gamma-Glu-Cys)n-Gly]. These peptides

appear upon induction of plants with metals of the transition and main groups (Ib-Va, Z

= 29-83) of the periodic table of elements. These peptides, called phytochelatins (PC),

are induced in all autotrophic plants so far analyzed, as well as in select fungi. Some

species of the order Fabales and the family Poaceae synthesize aberrant PC that

contain, at their C-terminal end, either beta-alanine, serine or glutamic acid. For this

group of peptides the name iso-PC is proposed. The biosynthesis of PC proceeds by

metal activation of a constitutive enzyme that uses glutathione (GSH) as a substrate;

this enzyme is a gamma-glutamylcysteine dipeptidyl transpeptidase which was given

the trivial name PC synthase. It catalyzes the following reaction: gamma-Glu-Cys-Gly +

(gamma-Glu-Cys)n-Gly-->(gamma-Glu-Cys)n+1-Gly + Gly. The plant vacuole is the

transient storage compartment for these peptides. They probably dissociate, and the

metal-free peptide is subsequently degraded. Sequestration of heavy metals by PC

confers protection for heavy-metal-sensitive enzymes. The isolation of a Cd(2+)sensitive cadl mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana, that is deficient in PC synthase,

demonstrates conclusively the importance of PC for heavy metal tolerance. In spite of

the fact that nucleic acid sequences and proteins are found in higher plants that have

distant homology to animal metallothioneins, there is absolutely no experimental

evidence that these "plant metallothioneins' are involved in the detoxification of heavy

metals. PC synthase will be an interesting target for biotechnological modification of

heavy metal tolerance in higher plants.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8955625 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2005;18(4):339-53.

Molecular mechanisms of heavy metal hyperaccumulation and phytoremediation.

Yang X, Feng Y, He Z, Stoffella PJ.

A relatively small group of hyperaccumulator plants is capable of sequestering heavy

metals in their shoot tissues at high concentrations. In recent years, major scientific

progress has been made in understanding the physiological mechanisms of metal

uptake and transport in these plants. However, relatively little is known about the

molecular bases of hyperaccumulation. In this paper, current progresses on

understanding cellular/molecular mechanisms of metal tolerance/hyperaccumulation

by plants are reviewed. The major processes involved in hyperaccumulation of trace

metals from the soil to the shoots by hyperaccumulators include: (a) bioactivation of

metals in the rhizosphere through root-microbe interaction; (b) enhanced uptake by

metal transporters in the plasma membranes; (c) detoxification of metals by

distributing to the apoplasts like binding to cell walls and chelation of metals in the

cytoplasm with various ligands, such as phytochelatins, metallothioneins, metalbinding proteins; (d) sequestration of metals into the vacuole by tonoplast-located

transporters. The growing application of molecular-genetic technologies led to the well

understanding of mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance/accumulation in plants, and

subsequently many transgenic plants with increased resistance and uptake of heavy

metals were developed for the purpose of phytoremediation. Once the rate-limiting

steps for uptake, translocation, and detoxification of metals in hyperaccumulating

plants are identified, more informed construction of transgenic plants would result in

improved applicability of the phytoremediation technology.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16028496 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2010 Mar;30(1):23-30.

Understanding molecular mechanisms for improving phytoremediation of heavy metalcontaminated soils.

Hong-Bo S, Li-Ye C, Cheng-Jiang R, Hua L, Dong-Gang G, Wei-Xiang L.

Heavy metal pollution of soil is a significant environmental problem with a negative

potential impact on human health and agriculture. Rhizosphere, as an important

interface of soil and plants, plays a significant role in phytoremediation of

contaminated soil by heavy metals, in which, microbial populations are known to affect

heavy metal mobility and availability to the plant through release of chelating agents,

acidification, phosphate solubilization and redox changes, and therefore, have

potential to enhance phytoremediation processes. Phytoremediation strategies with

appropriate heavy metal-adapted rhizobacteria or mycorrhizas have received more and

more attention. In addition, some plants possess a range of potential mechanisms that

may be involved in the detoxification of heavy metals, and they manage to survive

under metal stresses. High tolerance to heavy metal toxicity could rely either on

reduced uptake or increased plant internal sequestration, which is manifested by an

interaction between a genotype and its environment.A coordinated network of

molecular processes provides plants with multiple metal-detoxifying mechanisms and

repair capabilities. The growing application of molecular genetic technologies has led

to an increased understanding of mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance/accumulation

in plants and, subsequently, many transgenic plants with increased heavy metal

resistance, as well as increased uptake of heavy metals, have been developed for the

purpose of phytoremediation. This article reviews advantages, possible mechanisms,

current status and future direction of phytoremediation for heavy-metal-contaminated

soils.

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19821782 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012

Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2003;10(5):335-40.

Heavy metals in plants and phytoremediation.

Cheng S.

GOAL, SCOPE AND BACKGROUND:

In some cases, soil, water and food are heavily polluted by heavy metals in China. To

use plants to remediate heavy metal pollution would be an effective technique in

pollution control. The accumulation of heavy metals in plants and the role of plants in

removing pollutants should be understood in order to implement phytoremediation,

which makes use of plants to extract, transfer and stabilize heavy metals from soil and

water.

METHODS:

The information has been compiled from Chinese publications stemming mostly from

the last decade, to show the research results on heavy metals in plants and the role of

plants in controlling heavy metal pollution, and to provide a general outlook of

phytoremediation in China. Related references from scientific journals and university

journals are searched and summarized in sections concerning the accumulation of

heavy metals in plants, plants for heavy metal purification and phytoremediation

techniques.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

Plants can take up heavy metals by their roots, or even via their stems and leaves, and

accumulate them in their organs. Plants take up elements selectively. Accumulation

and distribution of heavy metals in the plant depends on the plant species, element

species, chemical and bioavailiability, redox, pH, cation exchange capacity, dissolved

oxygen, temperature and secretion of roots. Plants are employed in the

decontamination of heavy metals from polluted water and have demonstrated high

performances in treating mineral tailing water and industrial effluents. The purification

capacity of heavy metals by plants are affected by several factors, such as the

concentration of the heavy metals, species of elements, plant species, exposure

duration, temperature and pH.

CONCLUSIONS:

Phytoremediation, which makes use of vegetation to remove, detoxify, or stabilize

persistent pollutants, is a green and environmentally-friendly tool for cleaning polluted

Sumber: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14535650 …. Diunduh 7/5/2012.

soil and water. The advantage of high biomass productive and easy disposal makes

. Phytoremediation of Mercury-Contaminated Mine Tailings by Induced Plant-Mercury

Accumulation

a1c1

Fabio N. Moreno , Chris W. N. Anderson a1, Robert B. Stewart a1 and Brett H. Robinson

Environmental Practice (2004), 6 : pp 165-175

In most contaminated soils and mine tailings, mercury (Hg) is not readily available for

plant uptake. A strategy for inducing Hg mobilization in soils to increase accumulation