Private Sector CP – Squirtle Squad – WSDI 2014

advertisement

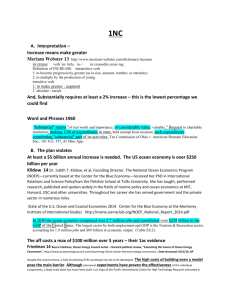

Private Sector CP – Squirtle Squad – WSDI 2014 Solvency General The private sector can solve—and be more cost-efficient Woll 12 (Woll, S., WeatherFlow Inc., “The role of the private sector in ocean sensing,” IEEE Xplore, Oct. 19 2012, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=6405082&abstractAccess=no&userType=inst) Recent years have seen the development of innovative and often lower-cost ocean observing technologies, putting more capability than ever into the hands of private sector companies, in some cases for the first time. At the same time, activity by private sector companies in the coastal oceans has increased in support of oil and gas exploration, offshore wind energy, homeland security, maritime shipping, fisheries, and other drivers. Oceanographic data from private sector sources has the potential to fill in existing data gaps in a cost-effective manner. In order to optimize our ability to make use of such data, a discussion of the policy surrounding the use of private sector data (and of the underlying data infrastructure needed to support it) is needed. This paper discusses some of the background, history, and considerations that have a bearing on the use of such private sector data.¶ The public sector is mishandling the oceans and the private sector has an incentive to step up Echelon 14 (Echelon Magazine, “Private sector push to prevent marine catastrophe,” Echelon Magazine, February 12, 2014, http://www.echelon.lk/home/private-sector-push-to-prevent-marine-catastrophe/) Dr P B Terney Pradeep Kumara, a scientist with the Department of Oceanography and Marine Geology at the Ruhuna University, recalls how he once encountered a man cutting sea grasses at Kapparathota in Weligama Bay. Sea grasses are flowering plants growing underwater in lagoons and bays and are the breeding grounds and habitat for a variety of marine life – a kind of cradle where marine creatures start their life. His inquiries revealed that some hotel managements in the area were in the habit of cutting the sea grass to make it easier for tourists to swim. “I spoke to the management of the hotel and stopped it,” recalled Pradeep Kumara. “But when I returned after a week I found the whole area cleaned up of sea grass.” The problem’s worse in other areas. Navy officers say the north-western coast from Devil’s Point to Pooneryn is thick with sea grass sedimentation – the debris that results from the use of bottom trawling nets – a banned technique – by Indian poachers. These are just two examples of the catastrophic destruction of the marine and coastal environment around the island that is taking place – bit by bit, year after year. The damage is so serious that the private sector is now getting involved in trying to enforce the regulations and ensure conservation. The plethora of laws and regulations and a multitude of state agencies charged with protecting natural resources have failed to do their job. Much is at stake, especially for the private sector, which has a vested interest in marine conservation as these resources and assets are of crucial commercial value to them, given the big investments being made in a range of sectors, from tourism to fisheries and offshore petroleum. Srilal Miththapala, past president of the Tourist Hotels Association, says a big chunk of the increased room capacity being built to cater to the increasing numbers of tourists will be on the coast, hence the need to protect it. “There are 9,000 rooms in the pipeline of which 35% will be on the coast – so it’s important to protect it,” he told a recent forum on marine conservation that brought together specialists and interested parties to assess the current status of marine conservation and the environment, promote awareness of conservation and strengthen enforcement. “The infrastructure is being built at a very rapid pace and therefore we must be mindful of what we are doing to the environment.” Most of the larger tourism developers are taking cognisance of environmental protection, which has virtually become a way of life for them, Miththapala notes. “It’s not only good ethical practice but a good marketing tool, because today many of the tourists coming to Sri Lanka are concerned about conservation. There is a market for tourists who are willing to pay a slightly higher premium to stay in such places.” Miththapala warns that the tourism sector should avoid going the way of the garment industry which began and thrived as sweatshops but shrank as the market changed and ‘ethical’ manufacturing and environmental conservation became important to buyers and consumers. “Today there are not more than 150 garment factories,” he says. “The others have all fallen by the wayside. Only those who can look after the environment survive. Firms like Brandix and MAS focus hugely on the environment. Tourism also has to do that. We always have had health and safety inspectors. Now we have environmental inspectors coming to see what we’re doing to the water, the beach and waste. If we don’t change we might also go the way the garment industry went.” The hotels association, which represents 154 hotels of the 200-odd hotels, plans to set up clusters of their members to monitor, record and do capacity building in support of conservation. Dr Hiran Jayewardene, a Cambridge-educated international lawyer specialising in maritime affairs, has watched the slow-motion marine catastrophe for decades. He was the live-wire behind the forum which saw the participation of business chambers and government conservation and environmental protection bodies, universities, and the navy and coast guard. “I see a failure of government institutions,” he declared, recalling the practical difficulties he ran into during the past three decades when he was in and out of government service, having done two stints as head of the National Aquatic Resources Agency. “They are unable to fulfil their role. They are not as effective as they should be. There are lots of constraints in the government that prevent us from getting ahead. So we looked at the private sector where we know there is good management.” The envisioned partnership is a logical alternative approach to conservation that exploits private sector skills and makes up for inadequacies in the public sector to ensure more effective management and protection of natural resources. Corruption and political interference in the enforcement of regulations hamper conservation efforts, especially at the local level. “There are politicians involved, unfortunately,” says Jayewardene, who also heads IOMAC (Indian Ocean Marine Affairs Cooperation), an organisation fostering co-operation among countries in the region. Law enforcement has deteriorated to such an extent that scientists like Dr Pradeep Kumara say they prefer to have the protection of the military when they make field visits for monitoring and data collection. “Strengthening the coast guard and navy would help. If we go with government officers we face problems from politicians and thugs. But if we go with the navy we have some protection.” The navy, which spends more time at sea than anyone else, is well-positioned to enforce regulations and support conservation. “We can have legislation but who would enforce the law?” asks Navy Commander Vice Admiral Jayanath Colombage, who spent eight of his 35 years of naval service totally at sea. “The ocean is our domain. And when not at sea, we are at the coast, where the ocean meets land. We collect data and we report things. We observe the change most of all. We’re losing the coast gradually.” Examples of navy support for research include river plume and marine mammal observation. “We have a huge problem in the northern, north-eastern and north-western coasts with Indian poaching,” Colombage says. “They use very destructive methods of fishing such as bottom trawling which scrapes the bottom, destroying coral and fish. Of the harvest, 35% is by-catch which is of no use. If we allow this to continue we will lose our livelihoods and it will have an impact on the economy.” Lagoons and estuaries on the coastal belt where the mixing of saline and fresh water linked to the rainy seasons create a unique environment for marine life are being destroyed. “If the lagoon mouth is damaged, the eco-system shifts to a high or low salinity scenario which affects marine life,” explains Professor Tilak Gamage of the Faculty of Marine Sciences at the Ruhuna University. This has been highlighted with dramatic effect at Koggala lagoon where the sand bar at the lagoon mouth which regulates the water flow was breached following excavation exceeding permitted levels. The lagoon mouth is now open to sea throughout the year and salinity levels have risen drastically changing the dispersion of mangroves and distribution of species. As a result the mud crab population is diminishing. Many of the 86 lagoons have similarly been mishandled, disturbing the exchange of water with the sea, causing fisheries to decline. “Most problems are caused by poor decision-making,” says Professor Gamage. “There’s a need to give priority to ecological values.” Private Sector better at spending- government sector work incentives poor and spending inefficient Muhlenkamp ’12 (10/26/12,Ronald H. Muhlenkamp is an award-winning investment manager, frequent guest of the media, and featured speaker at investment shows nationwide, Ron’s entire business career has been devoted to the professional management of investment portfolios. His work since 1968 has been focused on extensive studies of investment management philosophies, both fundamental and technical. As a result of this research, he developed a proprietary method of evaluating both equity and fixed income securities, which continues to be employed by Muhlenkamp & Company. In addition to publishing his quarterly newsletter, Muhlenkamp Memorandum, Mr. Muhlenkamp is the author of Ron’s Road to Wealth: Insights for the Curious Investor. Mr. Muhlenkamp received, and a Masters in Business Administration from the Harvard Business School in 1968. He holds a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation, “Private Sector Better at Spending Money than the Government”, Originally published in the Pittsburgh Business Times, October 26, 2012, http://www.muhlenkamp.com/whatsnew/marketcommentary/private_sector_better_at_spending_money_than_government) In 1980, I spent an afternoon with my old college roommate, Mike, and his wife, Cindy. Cindy and I got into an argument that Mike finally summed up (and thankfully ended) with, “Ron, you believe that the average person, dumb as he may be, is better at making his/her own decisions and spending his/her own money than a highly educated, well-meaning person in Washington, D.C., can do it for him?” I said, “Absolutely!” He continued, “Cindy, you believe that an intelligent, highly educated, well-meaning person in Washington, D.C., can spend the average person’s money better than that person can do it for himself.” She said, “That’s right!” I can’t summarize the argument any better than Mike did. The trouble with government spending is that the government doesn’t have any money. Every dollar spent by the government must be raised—either through taxes or through borrowing. We’ve heard a lot about the borrowing to cover the federal deficit, but we don’t hear much about the taxes. For most of us, we only see the taxes that are on our annual tax return and our W-2 forms. The W-2 lists our gross pay along with deductions for Social Security and Medicare (FICA), federal withholding, state, and local taxes. But this is only part of the story. The other part is the taxes paid by the employer, which the employee never sees. The following table shows the W-2 numbers for someone making a gross income of $45,000.00 per year in 2012. The table also shows the amounts paid by the employer for FICA, various unemployment taxes, health care insurance, and so on. As you can see, for the employee to take home $37,610.00 it costs the employer $81,393.45. Specifically, for my employee to take home $1.00 it costs me $2.16. So he must produce $2.36. The twenty cents is my “profit” for hiring him. (In fact, the average profit-to-payroll in the U.S. economy is 6%–9 percent.) Based on the above, I would suggest that personal and national wealth production only occurs in the private (nongovernmental) market because when the government gets involved, work incentives decrease, and spending becomes less efficient. So what’s the problem with government spending? It moves resources from the private sector (slowing the economy and decreasing employment) into the government sector where work incentive is poor and spending is inefficient. It assumes a well-meaning individual in Washington can spend our money better than we can, but government spending has none of the incentive effects that drive the economy. Aquaculture Private Companies can solve for aquaculture WorldFish 12 (World Fish, Organizes research on all aspects of fisheries and other living aquatic resources. Details of publications, research, services, projects, staff, “The private sector: partnering for poverty relief and profit,” World Fish,11/5/12, http://www.worldfishcenter.org/news-events/private-sector-partnering-povertyrelief-profit#.U8bHf_ldVjI) Addressing the problems of poverty and malnutrition in low-income communities is usually the preserve of government agencies and development organizations. However, with demand for fish products soaring worldwide, the small-scale fisheries sector in developing nations represents a potentially lucrative – as well as ethical – opportunity for private sector investors. WorldFish has formed partnerships with a number of private sector partners to create a win–win scenario for business and local communities alike.¶ ¶ When Mohammed Gouda, an engineer and businessman, started a fish farming business in 1984, he was the first in the Fayoum Province south of Cairo, Egypt. By 1993, there were enough fish farmers in the region for Gouda to establish a fish farming collective, and since 1998, Gouda has developed a partnership with WorldFish on a number of endeavors, beginning with WorldFish training for his collective.¶ ¶ “Training is very important,” explains Gouda, “we did training, and then together we made a trial farm here on how to increase production and to improve species of Tilapia.” The genetic improvement program is now in its 10th breeding generation, and Gouda expects the program to continue with WorldFish’s input. The focus will be on developing fast-growing and disease-resistant varieties for improved yield, and cold-tolerant varieties to withstand the winter months. Ocean Floor Mapping Ocean Floor mapping should be left to the private sector McLaughlin 14 (Dan McLaughlin, writer for Redstate, “De-Privatization: Democrats Looking to Soak The Taxpayers”, July 1,2014, http://archive.redstate.com/stories/policy/de_privatization_democrats_looking_to_soak_the_taxpayer) Leaving aside a pun he had probably spent years waiting to use, David Freddoso has an excellent piece on the complete collapse of opposition to a big-ticket new ship for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's ocean-floor-mapping project. NOAA, of course, takes up close to 60% of the budget of the Commerce Department, whose budget I looked at in greater detail here. Freddoso's point is that ocean-mapping is a classic example of a function that should be left to the private sector or, at a minimum, contracted out to private companies rather than performed by more-expensive government employees: Environmentalism The Free Markets solve environmental issues better empirically than the public sector and are more responsive- the public sector lacks liability incentives and farsighted behavior Stroup ‘8 (Richard L. Stroup is president of the Political Economy Research Institute and visiting professor of economics at North Carolina State University, both in Raleigh, North Carolina. He is also a senior associate with the Property and Environment Research Center in Bozeman, Montana. From 1982 to 1984, he was director of the Office of Policy Analysis, U.S. Department of the Interior, “Free Market Environmentalism”, Library of Economics and Liberty, the Library of Economics and Liberty is dedicated to advancing the study of economics, markets, and liberty. It offers a unique combination of resources for students, teachers, researchers, and aficionados of economic thought., http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/FreeMarketEnvironmentalism.html) Free-market environmentalism emphasizes markets as a solution to environmental problems. Proponents argue that free markets can be more successful than government—and have been more successful historically—in solving many environmental problems. This interest in free-market environmentalism is somewhat ironic because environmental problems have often been seen as a form of market failure (see public goods and externalities). In the traditional view, many environmental problems are caused by decision makers who reduce their costs by polluting those who are downwind or downstream; other environmental problems are caused by private decision makers’ inability to produce “public goods” (such as preservation of wild species) because no one has to pay to get the benefits of this preservation. While these problems can be quite real, growing evidence indicates that governments often fail to control pollution or to provide public goods at reasonable cost. Furthermore, the private sector is often more responsive than government to environmental demands. This evidence, which is supported by much economic theory, has led to a reconsideration of the traditional view. The failures of centralized government control in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union awakened further interest in free-market environmentalism in the early 1990s. As glasnost lifted the veil of secrecy, press reports identified large areas where brown haze hung in the air, people’s eyes routinely burned from chemical fumes, and drivers had to use headlights in the middle of the day. In 1990 the Wall Street Journal quoted a claim by Hungarian doctors that 10 percent of the deaths in Hungary might be directly related to pollution. The New York Times reported that parts of the town of Merseburg, East Germany, were “permanently covered by a white chemical dust, and a sour smell fills people’s nostrils.”For markets to work in the environmental field, as in any other, rights to each important resource must be clearly defined, easily defended against invasion, and divestible (transferable) by owners on terms agreeable to buyer and seller. Well-functioning markets, in short, require “3-D” property rights. When the first two are present—clear definition and easy defense of one’s rights—no one is forced to accept pollution beyond the standard acceptable to the community. Local standards differ because people with similar preferences and those seeking similar opportunities often cluster together. Parts of Montana, for example, where the key economic activity is ranching, are “range country.” In those areas, anyone who does not want the neighbors’ cattle disturbing his or her garden has the duty to fence the garden to keep the cattle out. On the really large ranches of range country, that solution is far cheaper than fencing all the range on the ranch. But much of the state is not range country. There, the property right standards are different: It is the duty of the cattle owner to keep livestock fenced in. People in the two areas have different priorities based on goals that differ between the communities. Similarly, the “acceptable noise” standard in a vibrant neighborhood of the inner city with many young people might differ from that of a dignified neighborhood populated mainly by well-to-do retirees. “Noise pollution” in one community might be acceptable in another, because a standard that limits one limits all in the community. Those who sometimes enjoy loud music at home may be willing to accept some of it from others. Each individual has a right against invasion of himself and his property, and the courts will defend that right, but the standard that defines an unacceptable invasion can vary from one community to another. And finally, when the third characteristic of property rights—divestibility—is present, each owner has an incentive to be a good steward: preservation of the owner’s wealth (the value of his or her property) depends on good stewardship. Environmental problems stem from the absence or incompleteness of these characteristics of property rights. When rights to resources are defined and easily defended against invasion, all individuals or corporations, whether potential polluters or potential victims, have an incentive to avoid pollution problems. When air or water pollution damages a privately owned asset, the owner whose wealth is threatened will gain by seeing—in court if necessary—that the threat is abated. In England and Scotland, for example, unlike in the United States, the right to fish for sport and commerce is a privately owned, transferable right. This means that owners of fishing rights can obtain damages and injunctions against polluters of streams. Owners of these rights vigorously defend them, even though the owners are often small anglers’ clubs with modest means. Fishers clearly gain, but there is a cost to them also. In 2005, for example, Internet advertisements offered fishing in the chalk streams of the River Anton, Hampshire, at 50 pounds British per day, or about $90 U.S. On the River Avon in Wiltshire, the price per day was 150 pounds, or $270. Valuable fishing rights encouraged their owners to form an association prepared to go to court when polluters violate their fishing rights. Such suits were successful well before Earth Day in 1970, and before pollution control became part of public policy. Once rights against pollution are established by precedent, as these were many years ago, going to court is seldom necessary. Potential plaintiffs who recognize they are likely to lose do not want to add court costs to their losses. Thus, liability for pollution is a powerful motivator when a factory or other potentially polluting asset is privately owned. The case of the Love Canal, a notorious waste dump, illustrates this point. As long as Hooker Chemical Company owned the Love Canal waste site, it was designed, maintained, and operated (in the late 1940s and 1950s) in a way that met even the Environmental Protection Agency standards of 1980. The corporation wanted to avoid any damaging leaks, for which it would have to pay. Only when the waste site was taken over by local government—under threat of eminent domain, for the cost of one dollar, and in spite of warnings by Hooker about the chemicals—was the site mistreated in ways that led to chemical leakage. The government decision makers lacked personal or corporate liability for their decisions. They built a school on part of the site, removed part of the protective clay cap to use as fill dirt for another school site, and sold off the remaining part of the Love Canal site to a developer without warning him of the dangers as Hooker had warned them. The local government also punched holes in the impermeable clay walls to build water lines and a highway. This allowed the toxic wastes to escape when rainwater, no longer kept out by the partially removed clay cap, washed them through the gaps created in the walls. The school district owning the land had a laudable but narrow goal: it wanted to provide education cheaply for district children. Government decision makers are seldom held accountable for broader social goals in the way that private owners are by liability rules and potential profits. Of course, anyone, including private parties, can make mistakes, but the decision maker whose private wealth is on the line tends to be more circumspect. The liability that holds private decision makers accountable is largely missing in the public sector. Nor does the government sector have the long-range view that property rights provide, which leads to protection of resources for the future. As long as the third D, divestibility, is present, property rights provide longterm incentives for maximizing the value of property. If I mine my land and impair its future productivity or its groundwater, the reduction in the land’s value reduces my current wealth. That is because land’s current worth equals the present value of all future services. Fewer services or greater costs in the future mean lower value now. In fact, on the day an appraiser or potential buyer can first see that there will be problems in the future, my wealth declines. The reverse also is true: any new way to produce more value—preserving scenic value as I log my land, for example, to attract paying recreationists—is capitalized into the asset’s present value. Because the owner’s wealth depends on good stewardship, even a shortsighted owner has the incentive to act as if he or she cares about the future usefulness of the resource. This is true even if an asset is owned by a corporation. Corporate officers may be concerned mainly about the short term, but as financial economists such as Harvard Business School’s Michael C. Jensen have noted, even they have to care about the future. If current actions are known to cause future problems, or if a current investment promises future benefits, the stock price rises or falls to reflect the change . Corporate officers are informed by (and are judged by) these stock price changes. This ability and incentive to engage in farsighted behavior is lacking in the political sector. Consider the example of Seattle’s Ravenna Park. At the turn of the twentieth century it was a privately owned park that contained magnificent Douglas firs. A husband and wife, Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Beck, had developed it into a family recreation area that, in good weather, brought in thousands of people a day. Concern that a future owner might not take proper care of it, however, caused the local government to “preserve” this beautiful place. The owners did not want to part with it, but the city initiated condemnation proceedings and bought the park. But since they had no personal property or income at stake, local officials allowed the park to deteriorate. In fact, the tall trees began to disappear soon after the city bought it in 1911. A group of concerned citizens brought the theft of the trees to officials’ attention, but the logging continued. Gradually, the park became unattractive. By 1972 it was an ugly, dangerous hangout for drug users. The Becks, operating privately at no cost to taxpayers, but supported instead by user fees, had done a far better job of managing the park they had created. Could parks, even national parks like Grand Canyon or Yellowstone, be run privately, by individuals, clubs, or firms, in the way the Becks ran Ravenna Park? Would park users suffer if they had to support the parks they used through fees rather than taxes? Donald Leal and Holly Fretwell studied national parks and compared certain of them with state parks nearby. The latter had similar characteristics but, unlike the national parks, were supported in large part by user fees. The comparisons were interesting. Leal and Fretwell noted, in 1997, that sixteen state park systems earned at least half their operating funds from fees. The push for greater revenue led park managers to provide better services, and more people were served. For example, in contrast to nearby national parks with similar natural features, Texas state parks offered trail runs, fun runs, “owl prowls,” alligator watching, wildlife safaris, and even a longhorn cattle drive. Costs in the state parks were also lower. Park users seem happy to pay more at the parks when they enjoy more and better services. Private individuals and groups have preserved wildlife habitats and scenic lands in thousands of places in the United States. The 2003 Land Trust Alliance Census Tables list 1,537 local, state, and regional land trusts serving this purpose.1 Many other state and local groups have similar projects as a sideline, and national groups such as The Nature Conservancy and the Audubon Society have hundreds more. None of these is owned by the government. Using the market, such groups do not have to convince the majority that their project is desirable, nor do they have to fight the majority in choosing how to manage the site. The result, as the federal government’s Council on Environmental Quality has reported, is an enormous and healthy diversity of approaches. Private sectors has superior green supply changes Walker et al. 08 (Helen Walker, Centre for Research in Strategic Purchasing and Supply, School of Management, University of Bath, Claverton Down, Bath BA2 7AY, UK, Lucio Di Sisto, Darian McBain, Director of Blue Sky Green. She has worked in Australia and the UK with business and government in the areas of supply chain management, policy and sustainability. Darian’s current focus is combining research into the quantification of supply chain impacts with practical applications in business, “Drivers and barriers to environmental supply chain management practices: Lessons from the private sectors”, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 3/01/2008, Pages 69-85 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1478409208000083) Today as never before people are concerned with the environment and climate change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007). In the field of business and management , there is an increasing onus on the role of organisations in society (McWilliams and Siegel, 2000; Strandberg, 2002), and their responsibilities to minimise impacts upon the environment (Hart, 1995; Henriques and Sadorsky, 1999). One aspect of this is green supply chain management issues, and how organisations can maximise the potential of their suppliers to adopt green supply chain management practices (Srivastava, 2007; Zhu et al., 2005). Examples of green supply chain management practices could include reducing packaging and waste, assessing vendors on their environmental performance, developing more eco-friendly products and reducing carbon emissions associated with transport of goods. In some instances, improving environmental supply has been seen as beneficial as it can reduce costs and improve organisational performance (Carter et al., 2000; Hervani and Helms, 2005), or enhance a firm's reputation (Wycherley, 1999). Others have viewed environmental supply initiatives with more scepticism, as reactive to government environmental regulation such as cutting down on waste (Porter and Van de Linde, 1995), or as simple a ‘greenwash’ or PR exercise (Greer and Bruno, 1996). This study aims to look beyond the rhetoric and investigate the real as opposed to espoused reasons for organisations engaging in green supply chain management practices. The majority of studies of environmental supply chain management initiatives have been conducted in the private sector. This is unfortunate, as the public sector may, by virtue of its being concerned with societal development and ‘well-being’, be a setting conducive to environmental supply projects. It is difficult to interpret whether the preference for private sector studies indicates a lack of environmental supply practices in the public sector, or that the public sector is simply being under-researched. Rarely, studies attempt to include both private and public sector views of greening the supply chain (New et al., 2002), and this study adopts such an approach. This study contributes to environmental supply literature and seeks to answer the research questions: Private companies are working together to help the environment without the governments not key to sustainability The World Bank 12 (The World Bank, The World Bank is a United Nations international financial institution that provides loans to developing countries for capital programs. The World Bank is a component of the World Bank Group, and a member of the United Nations Development Group, “More than 80 nations, private companies and international organizations declare support for Global Partnership for Oceans, The World Bank/Global Partnership for Oceans (GPO), 7/16/2012, https://www.globalpartnershipforoceans.org/more-100-nations-private-companies-and-international-organizations-declaresupport-global) RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil, June 16, 2012 -- Over 100 countries, civil society groups, private companies and international organizations have declared their support for the new Global Partnership for Oceans (GPO), signaling their commitment to work together around coordinated goals to restore the world’s oceans to health and productivity. Among those throwing their public support behind a “Declaration for Healthy and Productive Oceans to Help Reduce Poverty- English, French” at the Rio+20 conference are 17 private firms and associations including some of the largest seafood purchasing companies in the world, representing over $6 billion per year in seafood sales, as well as one of the world’s largest cruise lines. So far, 13 nations, 27 civil society groups, 17 private sector firms and associations, seven research institutions, five UN agencies and conventions, seven regional and multi-lateral organizations and seven private foundations are supporting the Declaration - totaling 83. Further support is expected in the run-up to the formal Rio+20 Conference. The Global Partnership for Oceans is a new and diverse coalition of public, private, civil society, research and multilateral interests working together for healthy and productive oceans. It was first announced in February 2012 by World Bank President Robert B. Zoellick at the World Oceans Summit and has been gathering growing support. Private sector support includes the seafood purchasing and food retailing companies, COSTCO, Darden Restaurants, Gorton's Inc., High Liner Foods Inc., Icelandic Group, Sanford Ltd. and Slade Gorton & Co., Inc. as well as cruise line, Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd, media production company MediaMobz and investors Paine & Partners and Oceanis Partners. The World Ocean Council, an international business alliance of 50 companies committed to corporate ocean responsibility, are also supportive of the new Partnership. Country supporters include: Australia, Iceland, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, the US Government’s overseas development arm, USAID, and the German Government’s Deutsche Geselleschaft fuer Technische Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) -- all participating as part of their commitment to international sustainable development. Coastal and island nations, including Fiji, Jamaica, Kiribati, Palau, Samoa, the Seychelles are also participants in the Partnership, which they see as key to providing coordinated support to their development needs. OTEC Private Companies are very interested in developing OTEC NOAA 11 (NOAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion,” Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, July 12, 2011, http://coastalmanagement.noaa.gov/programs/otec.html#top) In 1980, the Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Act granted the authority for licensing OTEC facilities located within the territorial sea of the United States to the Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).¶ At this time it was envisioned that OTEC technology would be producing 10,000 megawatts (MW) of electricity by 1999 which would power approximately ten million homes. Shortly after the OTECA Act was established, NOAA's Office of Coastal Resource Management (OCRM) established an OTECA program and in 1981, promulgated regulations.¶ By 1996, NOAA had not received any license application for a commercial OTEC facility. During the fifteen year time period, the risks to potential investors and low oil prices have limited commercial development. NOAA disbanded the OTECA licensing program and the OTEC regulations were rescinded (click here to view the record of the OTEC regulations removed in the Code of Federal regulations).¶ In 2008, oil prices rose again and several companies approached NOAA with questions about licensing requirements for OTEC facilities. Since then, millions of dollars have been invested by private companies in OTEC project planning and design. Applications for pilot and commercial facilities are expected in the near future. In addition, both the Navy and Department of Energy have recently made substantial grant awards for OTEC component and subsystems development. OCRM is now rebuilding its OTEC licensing capacity due to the recent interest in the technology. Private corporations are already establishing plans for OTEC facilities in the status quo Lockheed Martin ’13 (Lockheed Martin, a global security and aerospace company that employs about 113,000 people worldwide and is principally engaged in the research, design, development, manufacture, integration and sustainment of advanced technology systems, products and services, “Lockheed Martin and Reignwood Group Sign Contract To Develop Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Power Plant,” Lockheed Martin, October 20, 2014, http://www.lockheedmartin.com/us/news/pressreleases/2013/october/131030-mst-otec-lockheed-martin-and-reignwood-group-sign-contract-todevelop-ocean-thermal-energy-conversion-power-plant.html) Lockheed Martin and Reignwood Group have signed a contract to start design of a 10-megawatt Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) power plant, which, when complete, will be the largest OTEC project to date. Lockheed Martin is the industry leader in the development of OTEC technology, holding 19 related patents. The Lockheed Martin-Reignwood 10-megawatt plant is considered to be a crucial step in the full commercialization of OTEC. “The ocean holds enormous potential for terrawatts of clean, baseload energy,” said Dan Heller, vice president of new ventures for Lockheed Martin Mission Systems and Training. “Capturing this energy through a system like OTEC means we have the opportunity to produce reliable and sustainable power, supporting global security, a strong economic future and climate protection for future generations.” Under this initial contract, Lockheed Martin will provide project management, design and systems engineering services. “The signing of this contract reflects both companies’ passion for green energy projects, and our willingness as a team to bring forth an exciting new renewable energy source that directly benefits people of all nations,” said Shaohua Liu, senior vice president for Reignwood Group. In addition to the contract signing, Lockheed Martin also joined Reignwood Group in celebrating the ribbon cutting of Reignwood’s new Innovative Technology Center, located at their corporate Beijing headquarters. The Innovative Technology Center is designed after Lockheed Martin’s Energy Solutions Center in Arlington, Va., which showcases new ideas for alternative energy generation and energy infrastructure. “This OTEC agreement and the establishment of a joint Innovative Technology Center between Reignwood Group and Lockheed Martin represents an important milestone that brings our advanced technologies to bear on the important global issues of climate change and renewable energy,” said Dr. Ray O Johnson, senior vice president and chief technology officer for Lockheed Martin. Lockheed Martin takes a(n) comprehensive approach to solving global energy and climate challenges, delivering solutions in the areas of energy efficiency, smart energy management, alternative power generation and climate monitoring. The company brings high-level capabilities in complex systems integration, project management, information technology, cyber security, and advanced manufacturing techniques to help address these challenges. Today, Lockheed Martin is partnering with customers and investing talent in clean, secure, and smart energy – enabling global security, a strong economic future, and climate protection for future generations. Reignwood Group, a multinational enterprise headquartered in Beijing, China, strives to set the benchmark for a higher quality of life, continually investing in green-related industries, products and services to support this mission, including property, new energy, aviation, agriculture, luxury lifestyle, healthcare and sports and culture. Headquartered in Bethesda, Md., Lockheed Martin is a global security and aerospace company that employs about 116,000 people worldwide and is principally engaged in the research, design, development, manufacture, integration, and sustainment of advanced technology systems, products, and services. The Corporation’s net sales for 2012 were $47.2 billion. Wind The private sector is going to drive the wind energy market forward Graeber 14 (Daniel J. Graeber, writer and political analyst for oilprice.com, mostly on energy sector, Iraq and broader Middle East development, teaches media literacy courses at Grand Valley State University, “Private Sector Driving U.S. Wind Market Forward”, oilprice.com, April 17, 2014, http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/04/17/private-sector-driving-us-wind-market-forward.aspx) For the United States, 12 states combined to account for 80 percent of the wind-generated electricity last year and it was the oil-rich state of Texas that led the nation with nearly 36 million megawatthours of electricity generated from wind.¶ While the United States is behind in terms of offshore wind capacity, private sector intere st onshore like IKEA's may help drive the sector forward. IPCC said more than $50 billion was invested globally in wind power in 2009, though it still accounts for only a small fraction of the global electricity supply. IPCC warned a business-as-usual approach to energy may leave the global environment in ruins. The wind energy market is expanding rapidly. For IPCC, with the right policies in place, the global companies like IKEA, it's a business decision, but it may be one that drives the sector forward. potential for wind energy exceeds current global electricity production. For PPPs Good – General Private Public Partnerships ensure government benefits form strong incentives, private firms avoid bureaucratic issues, while both can experiment with technology and ensure the allocation of scarce capital resources Rondinelli n/d (Dennis A. Rondinelli was a professor and researcher of public administration and received his education from Rutgers University. He has written many books on foreign aid policy and development, including “Development Administration and U.S. Foreign Policy”,“Partnering for Development: Government-Private Sector Cooperation in Service Provision, PDF pages 3,4,5, Unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan006231.pdf) Moreover, the private sector can often manage more efficiently the entire supply chain needed to provide and distribute goods and services more effectively than can government agencies. Publicprivate partnerships can bring new ideas for designing programs and projects, and greater synergy between design and operation of facilities . Through public-private partnerships, governments can avoid expensive over-specification and design of public assets and focus on the life-of-project costs of initiating new activities or building new facilities. By outsourcing or working in partnership with the private sector, governments can benefit from the strong incentives for private firms to keep costs down. Often, p rivate firms can avoid the bureaucratic problems that plague national and municipal governments, and they can experiment with new technology and procedures. PPPs allow government to extend services without increasing the number of public employees and without making large capital investments in facilities and equipment. Private firms can often obtain a higher level of productivity from their work forces than can civil service systems, they can use part-time labor where appropriate, and they can use less labor- intensive methods of service delivery. Partnering with the private sector gives local governments the ability to take advantage of economies of scale. By contracting with several suppliers, governments can assure continuity of service. By contracting competitively for services, they can determine the true costs of production and thereby eliminate waste. 4 Cooperating with the private sector also allows governments to adjust the size of programs incrementally as demand or needs change. Partnerships that partially or completely displace inefficient SOEs can help reduce government subsidies or losses and relieve fiscal PPPs can usually respond more flexibly to "market signals," more easily procure modern technology, and develop stronger capacity to maintain infrastructure than can public agencies. Public-private sector cooperation can also generate jobs and income while meeting demand for public goods and services. At a time when private transfers far outpace the flow of official development assistance, partnerships pressures on the national treasury. are often the most effective way for governments in developing countries to mobilize private and foreign investment capital for infrastructure expansion or improvement. And to the extent that PPPs achieve their objectives they can contribute to increasing national productivity and economic output, assuring a more efficient allocation of scarce capital resources, accelerating the transition to a market economy, and developing the private sector. The United States has been using Private Public partnerships on road and transportation infrastructure for a long time- no reason wouldn’t work AECOM 7 (July 7, 2007, AECOM is a global provider of professional technical and management support services to a broad range of markets, including transportation, facilities, environmental, energy, water and government. “Case Studies of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships in the United States” (https://dlweb.dropbox.com/get/The%20Sophomoric%20Selection/3.%20Articles%20to%20Read/Finished%20Articl es/PPPs2.pdf?w=f66941e9) Private sector involvement in the provision of transportation infrastructure and services is not new to the United States. The first roadways were developed by the private sector in the late eighteenth century in the form of toll roads and turnpikes that opened passageways from the eastern seaboard to the virgin territories further inland. The private sector dominated the provision of roadway development until the twentieth century, when federal and state governments increased their involvement in funding road networks as the needs of a growing economy and population required improved accessibility and mobility beyond what the railroads could deliver on their fixed-rail systems. Until the establishment of a dedicated Highway Trust Fund and the initiation of the Interstate Highway System, the private sector played a major role in the development of the nations first major highways as tolled facilities, principally in the Northeast quadrant but also in other parts of the country like Florida, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Technological, managerial, and financial benefits all support the success behind Private –Public cooperation AECOM 7 (July 7, 2007, AECOM is a global provider of professional technical and management support services to a broad range of markets, including transportation, facilities, environmental, energy, water and government. “Case Studies of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships in the United States” (https://dlweb.dropbox.com/get/The%20Sophomoric%20Selection/3.%20Articles%20to%20Read/Finished%20Articl es/PPPs2.pdf?w=f66941e9) This definition emphasizes that with a PPP the public and private sectors share responsibility for the delivery of the project and/or its services. By expanding the private sector role, the public sector is better able to avail itself of the technological, managerial, and financial resources to leverage scarce public funds and expedite the delivery of a project and/or services in a more cost effective manner and with reduced risk to the public agency sponsor. As noted above, the public sector bore most project delivery, financial, and operational risks. By sharing responsibility and resources for the delivery of a PPP project, both public and private sectors share in the potential risks and rewards from the delivery of the facility or service relative to what they retain responsibility for. Net Benefits Politics – GOP GOP prefers private sector efforts Edwards 14 (David Edwards, editor of Raw Story, writes for Crooks and Liars and the BRAD BLOG, former network manager for the state of North Carolina and engineer developing enterprise resource planning software, “Mitch McConnell’s slogan to win non-GOP voters: ‘We are the party of the private sector’”, the Raw Story, 1/26/14, http://www.rawstory.com/rs/2014/01/26/mitch-mcconnells-sloganto-win-non-gop-voters-we-are-the-party-of-the-private-sector/) Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell on Sunday predicted that the Republican Party could win over independent and undecided voters by campaigning on the message that the GOP was “the party of the private sector.”¶ ¶ In an interview on Fox News Sunday, a viewer pointed out to McConnell that “Democratic bashing” could only take Republicans so far in winning undecided voters and reaching across the aisle to solve big problems.¶ ¶ Fox News host Chris Wallace wondered if there was a “positive GOP agenda.”¶ ¶ “Look, we believe that the American people will understand by this fall that we are the party of the private sector,” McConnell explained. “You know, we’ve tried big government now for six years in a row. We know that doesn’t work. We’ve had a tutorial, an experiment with spending and borrowing and taxing and regulating.”¶ ¶ “I think the American people, surveys indicate, are very skeptical of all these government programs the president continues to offer,” he added. “And we’re going to make the point that let’s try the private sector for a while, let’s make it easy to create jobs and opportunity for our people. The government is not going to get that job done. We’ve seen that.” AFF Perm SCOPE proves the private sector can work with the government successfully KHON’14 (Khon web team; Channel 2 Hawaii New in Honolulu; “UH receives largest ever private award for ocean research”; 16 June 2014; http://khon2.com/2014/06/16/uh-receives-largest-ever-private-awardfor-ocean-research/) The University of Hawaii has received the largest private foundation gift ever for its work in ocean ecology. Forty million dollars was awarded by The Simons Foundation to Edward DeLong and David Karl, professors in the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. The award is to fund the work of the two co-directors to lead the Simons Collaboration on Ocean Process and Ecology, or SCOPE. The program will use the field site Station ALOHA, located a little more than 62 miles north of Oahu. SCOPE is one of the programs of the Simons Foundation’s division of Life Sciences, which aims to advance basic research in life sciences. The announcement of the award was made at a press conference Monday at the UH Marine Center on Sand Island, in front of the docked research vessel the Kilo Moana. The program aims to further our understanding of the microscopic organisms that inhabit every drop of seawater by utilizing a range of advanced technologies, and how those tiny creatures control the movement and exchange of energy and nutrients. Microorganisms in the sea are responsible for producing oxygen that we breathe. They form the base of the food web for all of the fisheries of the world, and they are the organisms that can degrade human-produced pollutants. SCOPE will be a multi-institutional collaboration with inaugural partners at the University of California at Santa Cruz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Washington. The program also signals the launch of the Hawaii Innovation Initiative, which works in partnership with the private sector and government to build a third major economic sector for the state in the field of innovative research, in hopes of creating high-quality, living-wage jobs. DeLong is the first scientist to be hired by UH under the auspices of the initiative. No Solvency – OTEC Private Sector Firms won’t invest in OTEC DOE 13 (U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Federal Agency for Energy, “Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Basics,” Energy.gov Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, August 16, 2013, http://energy.gov/eere/energybasics/articles/ocean-thermal-energy-conversionbasics) In general, careful site selection is key to keeping the environmental effects of OTEC minimal. OTEC experts believe that appropriate spacing of plants throughout tropical oceans can nearly eliminate any potential negative effects on ocean temperatures and marine life.¶ OTEC power plants require substantial capital investment upfront. OTEC researchers believe private sector firms probably will be unwilling to make the enormous initial investment required to build large-scale plants until the price of fossil fuels increases dramatically or national governments provide financial incentives. Another factor hindering the commercialization of OTEC is that there are only a few hundred land-based sites in the tropics where deep-ocean water is close enough to shore to make OTEC plants feasible. No Solvency – Aquaculture Without government support aquaculture cannot be sustainable FAO 2006 (The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations is an agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger. Serving both developed and developing countries, FAO acts as a neutral forum where all nations meet as equals to negotiate agreements and debate policy. FAO is also a source of knowledge and information, and helps developing countries and countries in transition modernize and improve agriculture, forestry and fisheries practices, ensuring good nutrition and food security for all, “The state of world fisheries and aquaculture."; Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/a0699e/a0699e.pdf ) Generally, a government’s commitment to provide increased support to the aquaculture ¶ sector is a prerequisite for the sector’s sustainable development. The commitment ¶ takes the form of clear articulation of policies, plans and strategies and the availability ¶ of adequate funding support. The challenge, and a potentially constraining factor, is ¶ the level of commitment of governments, particularly those of developing countries. ¶ Will it falter and shift as new global economic opportunities arise and the competition ¶ for scarce financial and natural resources increases? While the level of commitment ¶ will vary within and among regions, depending on the importance of aquaculture in ¶ national economies and well-being, it is nonetheless expected that in countries where ¶ aquaculture contributes substantially, or is seen as a potential contributor, to growth, ¶ poverty alleviation and food security, the commitment will hold and the level of ¶ support increase. Corruption Turn Privatizing leads to corruption within private companies and in politics Bjorvath & Søreide 05 (Kjetil Bjorvath Bachelors in Macroeconomics, Microeconomics, MA Industrial economics and competition policy, Development economics, PhD International economics, Economic geography, Research: Economic geography, Economic development, Fiscal federalism, Tina Søreide research focuses on incentive-structures in governance institutions. She holds a PhD in economics from the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration (NHH) and a Master degree in economics from the University of Bergen. Her PhD project offered an extensive analysis of the causes and consequences of corruption. From 2008 to 2010, she was on leave from CMI to work on the Governance and Anti- Corruption (GAC) agenda at the World Bank, Washington, DC. Søreide teaches a course in political economy at the University of Bergen, Department of Economics, where incentive structures in governance is the cross-cutting theme., “European Journal of Political Economy”, Science Direct, 12/04/2005, Pages 903-914, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0176268005000133) In many cases, and in particular in developing and transition economies, concerns have been raised about the privatization process, both in terms of the price paid for the assets and the resulting effect on the local economy. Stories about corruption abound. In the words of Joseph Stiglitz (2002: 58): “Perhaps the most serious concern with privatization, as it has so often been practiced, is corruption. (...) Not surprisingly the rigged privatization process was designed to maximize the amount government ministers could appropriate for themselves not the amount that would accrue to the government's treasury let alone the overall efficiency of the economy”. One way for corrupt officials to rig the privatization process is to offer the acquiring firm a monopoly position in the post-privatized market. This increases the acquiring firm's willingness to pay for the state assets, and hence increases the amount that the government ministers are able to appropriate for themselves. Indeed, there are clear signs that corruption and market concentration go hand in hand. In an empirical study Ades and Di Tella (1999) report that: “...corruption is higher in countries where domestic firms are sheltered from foreign competition by natural or policy induced barriers to trade, with economies dominated by a few number of firms, or where antitrust regulation is not effective in preventing anti-competitive practices. The size of the effect is rather large...” This conclusion is consistent with Djankov et al. (2002) who argue that countries with greater regulation of entry have higher corruption and larger unofficial economies. A number of studies show that privatization does not necessarily lead to increased competition and efficiency. Manzetti (1999: 328) argues that many cases of privatization in South America have resulted in more market concentration, not less. Puntillo (1996) and Black et al. (2000) report that the hasty process of privatization in Russia in the 1990s often resulted in very limited improvements in productivity and negligible state revenues. Turnovec (1999) demonstrates that privatization in the Czech Republic was less successful than official statistics indicate in transferring state assets to the private sector, partly as a result of corrupt transactions. One reason why corruption may be a particularly severe problem in the sale of public assets is that it is typically very difficult to place a value on these assets. Hence, it is not easy for a third party to judge whether or not the price announced after the sale of the asset is reasonable. In the case of privatization, Rose-Ackerman (1999: 35) notes that: “Corrupt officials may present information to the public that makes the company look weak while revealing to favored insiders that it is actually doing well.” There may be a gap between the actual price of the asset and the price announced to the public, with the difference ending up in the pockets of corrupt bureaucrats and politicians. Environment Turn Handing over the ocean’s problems to the private sector could create far more problems than it solves Rey 14 (Nathalie Rey, “Global Partnership for Oceans: World Bank fishing in troubled waters?”, Brettonwoods Project, March 31 2014, http://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2014/03/world-banks-global-partnership-oceans-fishing-troubled-waters/) The World Bank has been involved in oceans-related projects for many years, however, in 2012 then Bank president Robert Zoellick upped the ante by announcing the launch of a new Global Partnership for Oceans (GPO, see Update 80). Together with a large range of partners from governments, businesses, civil society and scientists, the Bank claims it wants to give a political boost to restoring the health of the oceans by providing finance and knowledge to activate “proven solutions” to deal with three key problems of overfishing, pollution and habitat loss. However, there are concerns that pushing solutions, such as massive expansion of fish farming and handing over the management of marine life to the private sector could create far more problems than it solves. Will people and marine life really be prioritised over dollar signs? Private entities care about profit more than the environment Shah 10 (Anup Shah, a degree in computer science, “Water and Development”, Global Issues, 6/06/10, http://www.globalissues.org/article/601/water-and-development, Accessed by David Rawle 7/18/14) The above-mentioned documentary noted that the World Bank argues that the problem is not privatization itself, but that privatization is not being practiced properly. Yet, the market-based paradigm for such a vital resource has come under question. The earlier-mentioned WDM report as well as the documentary noted that the goals of a responsible government (universal access), and the goals of a private company (profit, typically by providing access to those who can pay) implies that private sector efficiency for profit may not mean that same efficiency will lead to universal access. Certainly, there are cases where markets have provided innovative ideas and efficiency in management. This typically requires a market where people that can pay for the service. For universal access, however, (which includes people who may not be able to pay, for a variety of reasons, and may require subsidies or assistance), a solely market-based privatization may be inappropriate. The United Nations Human Development Report, focusing on water, weighs in on this too, and adds: Some privatization programs have produced positive results. But the overall record is not encouraging. From Argentina to Bolivia, and from the Philippines to the United States, the conviction that the private sector offers a “magic bullet” for unleashing the equity and efficiency needed to accelerate progress towards water for all has proven to be misplaced. While these past failures of water concessions do not provide evidence that the private sector has no role to play, they do point to the need for greater caution, regulation and a commitment to equity in public-private partnerships. Two specific aspects of water provision in countries with low coverage rates caution against an undue reliance on the private sector. 1) The water sector has many of the characteristics of a natural monopoly. In the absence of a strong regulatory capacity to protect the public interest through the rules on pricing and investment, there are dangers of monopolistic abuse. 2) In countries with high levels of poverty among unserved populations, public finance is a requirement for extended access regardless of whether the provider is public or private. For poor countries, as argued elsewhere on this web site, pursuing neoliberal ideology too early goes counter to experiences from history; today’s wealthy countries did not prosper following these policies. They only used these policies once a market-based economy was already established and society had sufficiently developed. Problems of privatization of water are many [PDF formatted document the WDM adds]. For example, Alternatives are often not considered. Those private consultancies often follow a privatization ideology and they of course stand to win money from it. A major problem is that it is the government of the poor country left to pick up the pieces of failed privatization projects PDF formatted document. Privatization of such vital resources (a right for all to access even if they do not have money) risks losing democratic accountability, and as cases in Bolivia, Argentina, Chile and elsewhere have shown, soaring water prices as a result can lead to many, many people not affording a basic right, and even spark massive unrest; Profits from a private company can also be siphoned off elsewhere (often to other countries from where the company came) to their shareholders, and less is reinvested into the system itself; Investment is likely only on those parts of the system that may bring profit, leaving the government with less resources to deal with the other parts of the system; Earlier in 2001, the Institute for Food and Development Policy (also known as Food First) suggested that economic globalization is largely to blame for this water crisis. As if to turn around the World Bank’s point that privatization is not being practiced properly and more of it is needed, Food First counters that it is democracy not being practiced properly, so we need more democracy and democratic accountability, rather than less. The increased commoditization of a basic necessity and a public service “reduces the involvement of citizens in water management decisions.” Furthermore, “These companies argue that privatizing water is the best way to deliver it safely to a thirsty world. This is yet another area of potential disagreement. It is true that governments have done an abysmal job of protecting water within their boundaries. However, the answer is not to hand this precious resource over to transnational corporations who have escaped nation-state laws and live by no international law other than business-friendly trade agreements. The answer is to demand that governments begin to take their role seriously and establish full water protection regimes based on watershed management and conservation.”