Polio Human Demography Research Paper

advertisement

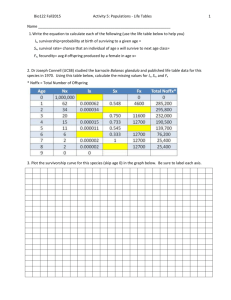

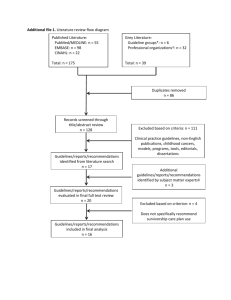

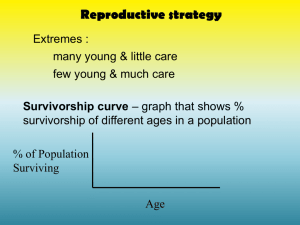

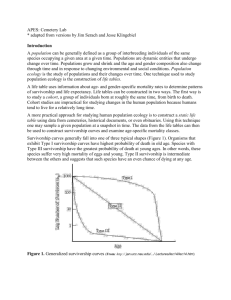

Kelsey Beechler BIOB 170 lab 11/11/13 Human Demography in the Gallatin Valley Introduction: Demography is a broad statistical study of human populations. Demography is important in science because it provides statistical data of diversity in populations and reveals trends within those populations. It is also important in society because it helps to analyze the relationships between economic, social, cultural, and biological processes influencing a population. The area of study for this research paper is the Gallatin County in Montana. Specifically, data will be collected from the cemeteries in Bozeman, Manhattan, Three Forks, and Gallatin Gateway. We will be studying the survivorship rates in Gallatin County from 1944-1954 and 1956-1966. It is a common practice within demography to take headstone data and compare it with statistical data and census numbers to see connections within the demographics of an area (Sattenspiel et al 2010). The population within this area during this time was fairly sparse with 16,124 people in 1930, but grew to 26,045 people in 1960 (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Despite this growth, the population still lived spread out over the county not creating any major city concentrations. Polio is a very contagious infectious disease that affected the nervous system and caused paralysis in mainly children, but could spread to anyone subjected to the disease through fecal-oral transmission (Singh et al. 2013). Most deaths occurred by suffocation due to respiratory paralysis. This required the ‘Iron Lung” to be used to keep individuals breathing. It became a very highlighted disease due to FDR contracting the disease and helping initiate the March of the Dimes fundraising organization. 1952-1954 contained multiple successful trials of the vaccine and oral drops by Salk and Sabin (Trevelyan et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2013). Around 1955, mass immunizations were occurring. The objective for this project is to study the survivorship rates from 1944-1954 and 1956-1966. Using this, we will look for a change from before and after the vaccination for poliomyelitis was distributed in 1955 in response to the poliomyelitis outbreak. Our research questions ask was there a decrease in survivorship in the 19441954 time period? Also, was there an increase in the survivorship in Gallatin County in the 1956-1966 time period, and if the increase exists, can it be attributed to the poliomyelitis vaccination being distributed in 1955? Our hypotheses state that by looking at data collected throughout the Gallatin County, there will be a low survivorship rate from 1944-1954 pre-poliomyelitis vaccine in 1955. Also, that by looking at the trends in the data from the 1944-1954 time period as compared to the 1956-1966 time period, there will be an increase in survivorship after the poliomyelitis vaccine is distributed in 1955. The null hypothesis states that the vaccine creates no difference in survivorship across the two tested time periods. This information and these data collection methods could lead to further connections with other infectious diseases and survivorship rates within a population. Methods: First we had to determine which areas within the Gallatin County would best represent the population during the mid 1900s. We chose Bozeman, Manhattan, Three Forks, and Gallatin Gateway. The specific cemeteries were Sunset Hills Cemetery, Bozeman, MT – 45°40’28”N 111°1’30”W, Salesville (Gallatin Gateway) Cemetery, Gallatin Gateway, MT – 45°36’47”N 111°11’46”W, Fairview Cemetery, Three Forks, MT - 45°52’17” 111°32’1”W, and Churchill Cemetery, Manhattan, MT – 45°45’4”N 111°17’59”W. To begin collecting data, we went out to the main cemeteries within each town and recorded information from the headstones on a chart. The chart included birth, death, age, and which decade category it fell into, be it 1944-1954 or 1956-1966. The data from all the cities would then be put on one chart, using Microsoft Excel, for each cohort. We calculated the survivorship by using the amount of individuals alive to the population of the city at the time. Life tables are used to record the age at death of our sample individuals. Then this allowed us to calculate the survivorship rate by dividing the total number of samples by the number of individuals alive. We then took this data and compared it over the different time cohorts. Also, we would gather survivorship data on a national level and see if the results are comparable. Results: Our data is displayed on two life charts. Figure 1 is the life chart for the 1944-1954 cohort, while Figure 2 is the life chart for the 1956-1966 cohort. By looking at the survivorship column on Figure 1, one can see there is a decrease in survivorship as the ages progress. In Figure 2, one can see a similar pattern. These patterns and their differences were then displayed on a survivorship curve graph for ease of comparison. Figure 1: Life chart for 1944-1954 cohort. Pre-vaccination Figure 2: Life table for 1956-1966 cohort. Post-vaccine Based on the data collected so far that has been displayed on a survivorship curve, the survivorship between the two cohorts shows some slight variations in certain age groups. The survivorship for the 1956-1966 cohort has a slight increase in comparison to the 1944-1954 cohort in the ages of 40-100 years old. There is also a slightly lower survivorship in the post-vaccination time cohort from ages 10-30 (Figure 3). Figure 3: Survivorship graph Discussion: Our hypotheses were looking for a low survivorship in the 1944-1954 cohort and an increase in the survivorship for the 1956-1966 cohort. We were looking for an increase in the survivorship from when poliomyelitis was most prevalent to when after the poliomyelitis vaccinations were distributed in 1955, in order to see a correlation between that event and the deaths of that time cohort. Our data does reflect an increase in survivorship for the post-vaccination cohort amongst a certain age groups. This could range to as much as a 10% increase. As we cannot distinguish what each individual that was recorded died from, we cannot definitively say that the poliomyelitis vaccine is the cause for the increase in survivorship. Our results did answer our objective, to find the survivorship rates and find a difference between the two cohorts of before and after the poliomyelitis vaccination in 1955. Some interesting points found within the data is that, while the disease affected children most, people aged 40 and below had a fairly high survivorship, while the old had the sharp decline. This could be due to the weaker immune systems of the elderly, but there is no explanation for the higher survivorship amongst the young. Compared to other demography research, we followed similar procedure and produced results based off of that. Our topic wasn’t replicated in any research we found, so our results are fairly unique. We also dealt with a more local approach, while many demography research projects were done a bit larger or national scale. By taking data from cemeteries, our data is automatically limited. People could have been buried elsewhere, we could have not collected the entire possible data for each area, and for some, they may not have been buried within a cemetery, but rather in a private plot. If there was to be future research done on the area with this topic, with more access, we could have gotten national records or health records for the area to see if poliomyelitis was documented in any way. Also, we could have accessed more of the areas within the county, thus giving us more thorough data. It is almost impossible to attribute all of these trends and records to a specific cause. During this era, there were flu epidemics, diseases and death from the war, and deaths due to the elderly generation dying of natural causes. Based off of our data, we have at least found something to contribute a correlation between the rise in survivorship and the vaccination distribution. With further research, more solid information could be found Literature Cited: Sattenspiel, Lisa, and Melissa Stoops. "Gleaning Signals About the Past From Cemetery Data." AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 142:7–21 (2010) 142 (2010): 7-21. Print. Singh, Robin, Amit K. Monga, and Souravh Bais. "POLIO: A REVIEW." International Journal of Pharmeceutical Sciences and Research 4.5 (2013): 1714-724. Print. Trevelyan, Barry, Matthew Smallman-Raynor, and Andrew D. Cliff. "The Spatial Dynamics of Poliomyelitis in the United States: From Epidemic Emergence to Vaccine-Induced Retreat, 1910–1971."Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95.2 (2005): 269-93. Print. " ." US Census Bureau. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2013. <http://www.census.gov/>.