Yarn Bombing: Claiming Rhetorical Citizenship in Public Spaces

advertisement

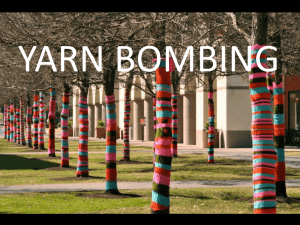

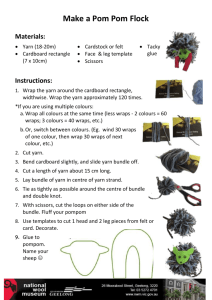

Yarn Bombing: Claiming Rhetorical Citizenship in Public Spaces Maureen Daly Goggin Arizona State University Rhetoric in Society Copenhagen, January16, 2013 TITLE SLIDE 1 Yarn bombing is a relatively new form of outsider1 or street art that is popping up all over the world in unexpected places, for unexpected reasons, and toward unexpected ends.2 The term was coined by Leanne Prain (a graphic artist, writer, knitter, and crafter) for her 2009 book titled Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti that she co-authored with Mandy Moore.3 The practice is also known by other names such as yarn storming, yarn graffiti, urban crochet and knitting, and guerilla crochet and knitting. SLIDE 2 Globally, women and men are taking up their knitting needles and crochet hooks to make political, social, cultural, aesthetic, and artistic statements. More recently the practice has become mainstreamed: commodified and commercialized. Ironically, it has become the very thing that outsider and contemporary artists in general and yarn bombers in particular are calling into question. In this paper, I look at those who engage this practice to claim full rights as rhetorical citizens worth listening to, seeing, and feeling in public spaces. Specifically, I examine protest yarn bombing across different countries on issues concerning: war, political decisions, economic problems, and environmental sustainability.4 Theories Grounding my exploration in “thing theory,” I argue that 2 SLIDE 3 pieces of outside art can be understood to constitute a materialist epistemology, what Davis Baird has termed “thing knowledge,” “where the things we make bear knowledge of the world, on par with the words we speak [emphasis added].”5 Indeed, the term yarn graffiti underscores this construct as the word “graffiti” comes from the Greek term γράφειν — graphein — meaning “to write.” What is written? When the graffiti artist who is credited with beginning the contemporary graffiti movement in Tehran, capital of Iran, was asked about the meaning of graffiti, SLIDE 4 the artist A1one (a.k.a. Tanha—a hindi word meaning “a lonely heart”) said: “A drawing on the street is similar to a letter: It proves that there is a writer.” Graffiti confirms the presence and reality of the “maker” in a public space that is typically controlled by and reserved for those in power. Graffiti expresses “thing knowledge.” Without official permission or permit, yarn bombing like graffiti is illegal, which is why many yarn bombers use pseudonyms to conceal their identities. In some spaces it is more tolerated than others and is not often prosecuted vigorously; nevertheless, it is seen in public spaces as “defacing property.” Where it differs from graffiti is that yarn bombing doesn’t damage property—it is easily removed and leaves no mark. In this way, it is a form of “girlie feminism,” a term coined by Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards in their Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future to describe the pro-femininity line of young feminists.6 Girlie feminism is a strand of third-wave feminism that seeks the validation of traditional female 3 activities by “valuing knitting, cooking and dressing up”7 and this strand rejects the confrontational tendencies of second-wave feminism. Although third-wave feminism is comprised of many contradictory strands of feminism, what most strands share is a political stance that is much gentler than the “kick the door” down strands of some second-wave feminists and of political groups in the US during the 1960s that fought for civil rights, witnessed Kennedy’s death, protested against the Vietnam war, and saw the downfall of Nixon. This softer tactic is evident in what some yarn bombers say about the act. For instance, Deadly Knitshade (a pseudonym for a yarn bomber in London) who coined the term “yarn storming” to deflect the association of the term “bombing” with war and violent tactics; she says: SLIDE 5 Change and making the world a better place can be done with a grin instead of a grimace, a whisper instead of a bellow. What we do can alter the way people look at their world. How it [yarn storming] alters it is up to them. That’s really our point.8 And as Dennis Stevens notes in discussing the Do-it-yourself or DIY movement: SLIDE 6 Rather than bringing revolution to the front door and kicking it open, as their parents may have hoped to do, these independent [DIY] makers are using the disarming and unassuming aesthetic of DIY craft’s remixed domestic creativity to make subversive statements about the world in which they live.9 4 So how are these folks—women and men—attempting to alter political and social views. We turn now to protest yarn bombing as acts of civil disobedience—a global practice for making subversive statements about political issues. Protests in Yarn Bombing—Political protest globally In April 2006, Danish artist Marianne Jorgensen created a war protest against the US and British involvement in the Iraqi war when she yarn bombed a World War II tank (borrowed after much negotiating with Danish government).10 SLIDE 7 Titled Pink M.24 Chaffee tank, the installation was made up of 3,500 pink crocheted squares donated by more than one thousand contributors from the US and Europe that were assembled together and fit over the borrowed combat tank. As a known artist, Jorgensen did not hide her identity but the thousand square makers remain anonymous. The piece was displayed in front of the Nikolaj Contemporary Art Center in Copenhagen. As Ele Carpenter points out about this protest, This symbolic transformation of military hardware into an object of comic irony seeks to disarm the offensive stance of a machine justified by its defensive capability. Whilst the sinister Trojan undertones of disguising a real weapon as soft and fluffy lead us to review the deaths from ‘friendly’ fire, as well as the women and children who suffer the largest percentage of deaths in most conflicts. Activist craft has many forms of symbolism and disguise. … [M]ost importantly the Pink M.24 Chaffee enables, or should enable, an alternative critical discourse about global militarism. 11 (4) 5 Carpenter’s point echoes Deadly Knitshade. Public spaces and the authority that typically regulates are subverted and transformed when they are filled with color, difference, and domestic work. 12 Protest against Political Decisions Yarn bombers challenge various political decisions. SLIDE 8 In this slide, we see the protest work of two young German university students currently in their 20s who call themselves by the pseudonyms Strick and Liesel (named after ‘Strickliesel’ or “Knitting Nancy,” a children’s toy used to learn how to knit). Their protest of nuclear power was a response to the German parliament passing a law in fall 2010 to extend the operation time of the country’s 17 nuclear power plants. At the top of the picture is the familiar anti-nuclear movement logo in the branded yellow and black, and the middle yellow and black sports the words “No thanks,” and the end white and black piece repeats the anti-nuclear logo. They hung banners of this design on trees, street lamps, bridge banisters and pillars in front of the state parliament building around Dusseldorf and Duisburg, where this banner was hung. SLIDE 9 In September 2012, an unknown crochet artist yarn bombed a political protest against the underground expansion of the city of Edinburgh’s tram line. Against a warm, soft, colorful blanket of crocheted granny squares is the message “Tramway to Hell.” In reaction to this anonymous installation, Yarnivore Rose (also a yarn bomber and yarn store owner) is reported to have said, “Actual political speech in yarnbomb form rather than ‘mere’ decoration! BRING IT ON!”13 Rose’s response resonates with the riot grrrl’s perspective of an anti-corporate stance 6 through self-sufficiency and self-reliance.14 The phrase “bring it on” works as a feminine proclamation. Economic Protests In the next slide, we turn to protests regarding economic problems. SLIDE 10 Here in 2011 Strick and Liesel installed a “throw-up” tag so named in graffiti to mean a message put up quickly, usually a signature. Here the message is “redundant” or “fired.” Placed in front of an abandoned facility that no doubt had “fired” many workers, leaving them unemployed the protest is underscored as part of a larger protest concerning job security and the economy. In June 2012, in Los Feliz, California SLIDE 11 outside the Bank of America on 1715 North Vermont Ave, in Los Angeles, the Knit Riot Collective (a group of guerrilla knitters and crafters) hung 99 hand-knitted houses among the ficus trees to protest the foreclosure crises. This yarnstorm was titled HOMEsweetHOME and was intended to demonstrate solidarity among Americans who have lost or are losing their homes to foreclosures. The Knit Riot Collective is quite active around LA and Hollywood, conducting economic protests and doing service for homeless. SLIDE 12 In June 2011, for instance, they yarn bombed the trees outside Highland Park Elementary School to protest the budget cuts from the school, hanging dollar bills from branches and wrapping treetrunks.15 In December 2011, they yarn bombed the PATH Homeless center in East 7 Hollywood, leaving a wall of knitted hats and scarves for the homeless to select as protection against the cold.16 On their blog they reported, “The warm fuzzy pieces went up in the dim morning light Saturday December 17th, and by 9 am hats and scarfs, hand knitted with love, could be seen being worn on the streets around the Mall.”17 Between February 2012 and September 2012, students in Québec held a series of student protests and demonstrations against a proposed raise in university tuition from $2,168 to $3,793 by 2017. SLIDE 13 Students throughout Québec participated in strikes. In March 2012, students posed with hand knitted protest signs. On March 22, 2012, 310,000 students were on strike and a demonstration which brought 300,000 people together took place in Montreal.18 Between February and September, students from the University of Montreal knitted and put together red squares (the symbol of student struggle first introduced in 2004) to form one of the economic protests. The strike ended on September 5, 2012 when a tuition freeze went into effect. Although students called an end to the strike that day, students from the University of Montreal still hung their protest quilt from the Jacques-Cartier Bridge in Montreal—with the message “the struggle is only starting.” Sustainability Protests We will look at just one more kind of protest—though there are many others— concerning environmental sustainability, specifically against three damaging practices: fracking, logging, and tire burning. SLIDE 14 8 As I was writing this paper, a yarn bombing protest against Fracking took place at St. Annes Square in Blackpool, England, on November 28, 2012.19 Fracking, as you may know, is a shale gas drilling technique that is now common in the US and being introduced and vehemently protested in Europe. “Environmentalists, as well as many people living near possible shale gas sites, worry about the huge quantities of water that fracking uses. They also fear that shale gas will prolong the fossil fuel era by reducing the incentive to switch to cleaner but more expensive energy sources like solar and wind.”20 For this protest, urban guerrilla knitters tied blue triangular crocheted tags to railings and trees that included a blue note. On one side of the note was a diagram of a drilling rig; the other side sported the phrase “Against Water F.O.W.L.E.R.S. Awareness Campaign” with contact details for the group and notification of an upcoming December 1, 2012 planned demonstration. The acronym F.O.W.L.E.R.S. stands for “Fracking Our Water Leaves Environmental Residential Stress.” Such non-violent activism is becoming increasingly popular around the globe. One Slide 15 group, the Knitting Nannas against Gas, a collection of activists in Australian, note that they “peacefully and productively protest against the destruction of our land and water by exploration and mining of coal seam gas and other none-renewable energy.”21 Chapters of this group are forming all around Australia. And like other groups, they are formed of men and women who participate in the acts of civil disobedience in public spaces. On February 16, 2012, a stretch of Highway 774 SLIDE 16 9 near Pincher Creek in Alberta, Canada was yarn bombed by a group protesting the practice of logging that was taking place just 4 kilometers south of the highway. The group, who as you can see wants to remain anonymous, targeted the trees so that those who passed by would “pause to reflect on the ‘knitting together’ of people, their communities, and the beauty in the space that surrounds them.”22 A spokesperson for the group described the installation as “creating a voice for wild spaces.”23 The knitted afghan on each tree works as a metaphor supplying warmth, nurturing, and protection against the devastation of logging while at the same time shouts its message. Finally, in the summer of 2012 in Beirut, Lebanon two designers, Hoda Baroudi and Maria Hibri founders of the Bokja Design store led a group to create a fabric and yarn bombing protest in Saifi Village against the political and civic practice of burning tires in the street. SLIDE 17 Increasingly, people in Beirut and elsewhere in Lebanon have been going to the street to burn tires in protest of the deaths of clerics such as Batroun and Akkar, the kidnapping of pilgrims in Syira, police activities, the frequent power outages, fights with family members, and so on. Of course, the problem is that burning tires releases dangerous gasses such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (type 1A carcinogen) and hazard particles such as lead, zinc, mercury, and chromium. The carcinogens from this dangerous practice build up in food and adversely affect the immune system and fertility. On July 3, 2012, the carefully wrapped tires were placed in an intersection and later taken to the entrance of Rafic Hariri International Airport. Later, on the Bokja Design facebook page, the designers wrote, “We took it to the streets. Someone wasn’t too happy about it. #WeDontCare #WeAreTyred.”24 10 Conclusion Yarn Bombing represents or better yet re-presents the convergence of several contemporary political and cultural strands: third-wave feminists, craft activists, Do-ItYourselfers, and contemporary artists. Some third-wave and contemporary radical feminists focus on practices that are counter-authority, counter-hegemony, and in the spirit of anarchy. Of these, some of them have turned to a specific kind of activism, the one we have been looking at here. Betsey Greer and Debbie Stoller25, for example, argue that the resurgence of interest in knitting and crocheting, especially among third-wave feminists, comes from an epistemic perspective that values making over made—that values production over consumerism.26 Greer has termed this interest craftivism27 (craft + activism; that is, activists who use art as a medium.). Emma Shephardis connects yarn bombing with Folk feminism where “‘authentic’ feminine cultural forms and practices are privileged over commercially produced popular culture and an attempt is made to unearth a women’s cultural tradition which has been hidden, marginalised or trivialised by a masculine cultural tradition and/or an inauthentic women’s culture.”28 In terms of the Do-it-yourself movement (DIY), Dennis Stevens points out: “If there is anything cohesive about the DIY movement, it’s that its practitioners choose to reinvent tradition as a remix, engaging with it through parody, satire and nostalgic irony. . . [T]his work makes its cultural [and I’d add political] statements indirectly and quietly.”29 Finally, a number of contemporary artists loudly question the use of galleries as exhibition spaces, curators and juries as judges, and commerce and consumerism that uses art. These new artists have turned to the streets, parks, and other outdoor spaces as exhibition sites for a variety of artistic media. 11 Drawing these strands together, we can understand yarn bombing as a contemporary response to the separation of labor and domestic skills, the split of public and private, the legal restrictions on making and mending anything, and on displaying anything in public. Yarn storming repurposes yarn to new ends. Repurposing theory helps to explain the attraction of this practice. In Ele Carpenter’s words, “Using the hacker language of reverse-engineering [or I’d term it repurposing] as a learning process--taking apart your jumper or video player to learn how to fix or reuse it” is the sign of DYI and in this case yarn storming, bombing, and graffiti. In sum, the practice of yarn bombing challenges many assumptions about arts and crafts, (i.e., high and low arts), male and female practices, handmade and mass made, hand wrought and machine wrought, public and private spaces, and personal and political issues. For this paper, we have looked at just one-slice of yarn bombing, that of protest activism. Let me end with political activist theorist, Randy Shaw’s words of advice to activists, SLIDE 18 Today’s activists must … recognize that their participation in public life will make a critical difference in their world. By acting proactively and with tactical and strategic wisdom, social change activists can bring a degree of social and economic justice . . . that has for too long been deferred. 30 The yarn bombers we have looked at and many others who use yarn to make political and cultural protests are accomplishing exactly what Shaw says needs to be done. Bring it on. Thank you. SLIDE 19 Thank you 12 NOTES 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outsider_art#Further_reading Start her if I decide to keep the term “outsider 2 Betsy Greer, Knitting for Good: A Guide to Creating Personal, Social, and Political Change, Stitch by art.” Stitch (Boston: Trumpeter, 2008); Deadly Knitshade, Knit the City: A Whodunnkit Set in London (Chichester: Summersdale, 2011); Mandy Moore and Leanne Prain, Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti (Vancouver: Arsenal Pump Press, 2009); Joan Tapper, Craft Activism: People, Ideas, and Projects from the New Community of Handmade and How You Can Join In (New York: Potter Craft, 2011); Simone Werle, Urban Knits (Munich: Prestel, 2011). 3 In 2007 a few books on contemporary knitting were published that had several yarn bombing pieces that were described as performative and subversive and activism. See, for example, Sabrina Shirobayashi, KnitKnit: Profiles and Projects from Knitting’s New Wave (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2007) and David Revere McFadden and Jennifer Scanlan, Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting (New York: Museum of Arts & Design, 2007). 4 This presentation draws from a larger study on yarn bombing in which I am exploring this practice as a contemporary, transnational form of transgressive rhetorical expression that takes place in cities, suburbs, and rural spaces from Austria to Zimbabwe, from Lebanon to Spain, from the US to China, and everywhere in between. Davis Baird, “Thing Knowledge—Function and Truth,” Techné 6.2 (Winter 2002): 13. Also see Davis 55 Baird: Thing Knowledge: A Philosophy of Scientific Instruments, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004. Also see Bruno Latour on things as active social agents. Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. 6 Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2000. 136. 7 Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, Manifesta [10th Anniversary Edition]: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future rev. ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. 216. 8 Deadly Knitshade, 124. 13 9 Dennis Stevens, “DIY: Revolution 3.0—Beta” (September 16, 2009). http://craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/diy-revolution-30-beta 10 http://studiostitchart.blogspot.com/2011/12/craft-process-in-contemporary-art.html 11 Ele Carpenter, “Activist Tendencies in Craft” Goldsmiths Research Online (2010), p. 4. Oai:eprints.gold.ac.uk:3109. 12 Emma Shepphardis, “‘It's Not a Hobby, It's a Post-apocalyptic Skill’: Space, Feminism, Queer, and Sticks and String,”Bad Subjects (2012). http://bad.eserver.org/issues/2012/notahobby 13 Cory Doctorow, “Yarn Bomb Transit Protest in Edinburgh.” Online at http://boingboing.net/2012/09/28/yarn-bomb-transit-protest-in-e.html 14 Sara Marcus, Girls to the Front: the True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. New York: Harper Collins, 2010. Also see her site at http://www.girlstothefront.com/ 15 http://www.knitriot.blogspot.com/ 16 http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/home_blog/2011/12/knitriot-path-homeless-center-.html 17 http://www.knitriot.blogspot.com/ 18 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2012_Quebec_student_protests#Red_square 19 http://stopfyldefracking.org.uk/latest-news/yarnbombing-st-annes/ 20 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/14/business/energy-environment/fracking-still-controversial-in- europe.html books. 21 https://www.facebook.com/KnittingNannasAgainstGas 22 http://stopcastlelogging.wordpress.com/2012/02/17/castle-yarn-bombing/ 23 Ibid. 24 http://www.facebook.com/pages/Bokja-Design-Studio/122659971080310 25 Debbie Stoller is founder of BUST magazine and the writer of the Stitch and Bitch series of knitting 14 26 Yarn bombing is temporal—an impermanent rather than permanent art object. While yarn installations may last for years—though the yarn will eventually disintegrate from harsh weather conditions--they are considered non-permanent, and, unlike other forms of graffiti, can be (and often are) easily removed if necessary. Really depends on so many things. The shortest I've had was less than half an hour and another I've had up for over a year.” (See http://www.flickr.com/groups/yarnbombingukdiy/discuss/72157614269938076/.) Given that it is unclear how long a piece will remain, yarn bombers are more invested in the process of creating the installation than in the finished product itself. Thus, it is the performance of yarn bombing that holds the meaning rather than the object. 27 Betsy Greer coined the term “craftivism” in 2003 to explain a third-wave feminist embrace of stitching, crochet, and knitting. American Craft Magazine put the term “craftavist” on one of the great moments in crafts to mark their 70th anniversary See http://craftcouncil.org/timeline/2000s.html and http://craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/70-years-making-timeline Also see Betsy Geer, "Craftivism." Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice. 2007. New York: SAGE Publications. Here she says: “Craftivism is a way of looking at life where voicing opinions through creativity makes your voice stronger, your compassion deeper & your quest for justice more infinite.” 28 Joanne Hollows, Feminism, Femininity, and Popular Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 29. 29 Dennis Stevens, “DIY: Revolution 3.0—Beta (September 16, 2009). http://craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/diy-revolution-30-beta 30 Shaw, Randy. The Activist’s Handbook rev. 2nd ed. 1996. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2001. 279.