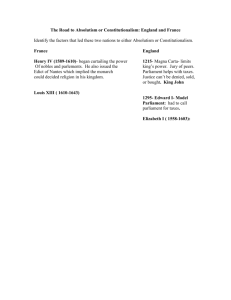

2302-2-the+legislature-definition+and+historical

advertisement

GOVT 2302 The Legislature Definition and Historical Background This first set of slides is intended to introduce you to the legislative branch and discuss its historical evolution prior to the ratification of the U.S. and Texas Constitutions. Here are a few basic facts about the legislative branch first. This is intended to clarify what the legislature is and what they look like in the US and Texas. We will provide detail for each of these in subsequent sections. A legislature is, simply put, an assembly of lawmakers. In the American governing system, the Legislature is designed to be the democratic branch of government. It is the one designed to be the most closely connected to the general population and is most subject to the shifting preferences of the public. Compare this to the executive, which has an autocratic design and the judiciary which is oligarchic in nature. Recall that the advantage of democracy of legitimacy, but the disadvantage is mob rule. This tells us something about the pros and cons of the legislature. The House of Representatives is notoriously combatative. The legislature is intended to provide legitimacy to the governing system. It embodies the principle of self-government. We are more likely, presumably, to think laws are fair – and worth following voluntarily - if we participated in their creation. Danger: The legislature can be prone to both mob rule and to tyranny of the majority. These tendencies are checked by the executive and judicial branches through the power of the veto and judicial review. Here’s some irony: Despite its connection to the general population, the U.S. Congress tends to be the least respected branch of government. See these figures from 2008. Gallup commentary. Notice that the further removed form popular control the institution is, the more people are likely to approve of it. It’s worth discussing why this might be the case. But is our criticism misplaced? Congress Bashing for Beginners It is ironic that the branch closest to the people has the lowest levels of public opinion. But perhaps that’s a direct result of the close control the people have with the institution. These are the basic functions of the legislature: 1 - Law Making 2 - Representation 3 – Checking the Executive and Judicial Branches Legislative Branches exist on every level in the American federal system. U.S. Congress State Legislatures City Councils Local Elected Boards The United States Congress and the Texas Legislature has met regularly since each respective Constitution was ratified. The U.S. Congress originally represented the people and the states equally. The House – the people The Senate – the states The national and state legislatures (except for Nebraska) are bicameral. One chamber is designed to be closely connected to the general population one is designed to be further removed from it. Lower Chamber Upper Chamber The lower chamber is usually called the House of Representatives The Lower Branch tends to be closely connected to small districts. Its members serve for short terms of office, but can be reelected, sometimes indefinitely. Lower branches tend to be large and are often subject to heated arguments. The United States House of Representatives has 435 members who represent one of 435 separate districts of approximately 600,000 people for 2 years terms. From the House website: The House Explained The Texas House of Representatives has 150 members who represent one of 150 separate districts of approximately 150,000 people for two year terms. They are designed to act as delegates and directly and quickly act on the immediate preferences of the public. All members are elected by the general population for two year terms. This allows for the potential for rapid turnover in response to shifts in public aproval. In reality, as we will discuss soon, this is rarely the case. Factors exist which secure the reelection of office holders (incumbents). Upper branches are usually called a Senate. The term comes from the Roman Senate Upper chambers are further removed from the direct preferences of the population either by how they are elected to office or by a large terms length They are designed to act as trustees and slowly, deliberately address the long terms needs of the republic. This is established by having senators serve for six year overlapping terms. The public has no ability to instantaneously change the composition of the Senate, as they can in the House. Originally, until the 17th Amendment, senators were elected by state legislatures, not the public. This touches on a key question concerning legislatures is how in fact it is able to turn the preferences of the general public into policy: should it be done quickly or slowly? How close should the connection be between the general public and the law? This is also a way to ask: How capable is the general public of supporting good public policy? Upper chambers tend to be calmer and more deliberative than Houses of Representatives. The United States Senate is sometimes called the worlds greatest deliberative body. We will discuss question whether that is still the case. It is the elite branch and is considered to be more prestigious than the House. The United States Senate is composed of 100 Senators, two from each state. Each state is represented equally despite the fact that the populations of states vary from a half million to almost 40 million. They serve for six year overlapping terms. The Texas Senate is composed of 31 members who represent each of 31 separate senatorial districts. Each district has about 600,000 members and they serve for 4 year overlapping terms. Legislatures on the national and state levels are dominated by two large political parties (Democrats and Republicans) which organize each institution internally and help recruit and run candidate for office. Here’s a history of party control of Congress. Legislatures also contain smaller institutions called committees which allow members to concentrate on the needs of constituents. Constituent is the fancy name used to describe the people who are represented by the member of Congress. But the terms can also refer to those who provide electoral support for a member. In January 2011 the U.S. Congress th convened for the 112 time since the ratification of Constitution. This Congress will therefore be called the 112th Congress. See also 2010 Congressional Elections. Here’s a link to a GIF file showing changes in Congressional control between 1900 – 1948. Also in January 2011 the Texas Legislature convened for the 82nd time since it became a state. This legislature will be called the 82nd Legislature. Legislatures exist on local levels as well, but they tend to be smaller, non-partisan, and are often unpaid. City Councils, the name most commonly given to municipal legislatures, are usually unicameral and tend to be divided into at large and single member districts. The purpose of single member districts is to ensure minority representation. Example: The Houston City Council is composed of 5 at large members and 9 single district members. It has recently been expanded due to population growth. Area City Councils of note: Alvin City Council Manvel City Council Pearland City Council Many single purpose governments have elected boards to oversee the operations of the administrative staff. Alvin ISD Board Houston ISD Board ACC Board HCC Board Now for some history The United States Congress can trace its direct evolution to Magna Carta, where an assembly barons forced King John to sign a document in 1215 not only placing limits on his powers, but allowing for the barons to form an assembly to oversee the actions of the King. We will, very roughly, trace the historical development of legislatures From the Security Clause of the Magna Carta to the British Parliament and the Congress under the Articles of Confederation Historical examples of legislative assemblies prior to this era are not common, but they did exist prior to the development of the British Parliament. Here are two: Athenian Assembly Roman Senate Each provides an example of the pros and cons of assemblies. The Athenian Assembly, which was composed of all Athenian citizens, was an example of direct democracy. But they approved the execution of Socrates and fell into anarchy thus allowing for the rise of the Thirty Tyrants. But the Roman Senate was a necessary check on the power of the executive. Julius Caesar’s assassination was an attempt to maintain the Roman Republic. Ancient assemblies provided a mixed record. On one hand, they were a source of instability and injustice, but on the other, they provided a necessary check on executive power. A key difference between the two was that the Athenian Assembly was direct (all citizens could vote) and the Roman Senate was indirect. In England prior to the Norman Invasion, monarchs would consult with elders in order to both consult and gain support for his proposals. After the Norman Invasion, William I established the King’s Council (the Curia Regis) as a substitute, but this was not a legislature as we would recognize it. The institution had no autonomous power. It was used by the King to ensure support for his proposals. It actually acted as a legislative and judicial institution as well as an advisory body for the executive. This violates our understanding of the separation of powers. Timeline results for the Curia Regis The purpose was to enable to king to rule directly. But this is concentrated power, which allows for abuse. An following the invasion, kings were beginning to do so. After the Norman Invasion, a strong monarchy evolved in Britain which replaced the feudal system. An administrative state was developed which allowed the monarch to effectively establish, implement and adjudicate the law. Kings claimed the power to rule absolutely, and developed the doctrine of the divine right of kings to support this absolute rule. In reality, Kings could only rule effectively if they kept the nobility and the clergy happy. If not, they could rally together to thwart the will of the king. Effective monarchs knew how to keep the peace, bad ones could not. Some could: King Henry I Some couldn’t: King John In order to establish a solid relationship with the nobility and the Church, Henry I (who ruled from 1100 – 1135) issued the Charter of Liberties which define voluntary limits on his power. But John (who ruled from 1199 – 1216) was regarded as being, all around, an abusive king. Rebellion by the barons was relatively easy to organize. Their combined efforts forced King John to recognize limits on his power, the rule of law, accept certain rights of freemen, respect legal procedures. King John refused to recognize these limits. Under the guidance of Stephen Langton, the barons (nobility) would organize in order to impose limits on the king. These were contained in the Magna Carta, which was loosely based on the Charter of Liberties. The intent of the barons was not to take control of the country, or to establish a democracy. They simply wanted to impose limits on the arbitrary powers of the king. They wished the rule of law to be applied to the king as it did to them. The document contained a variety of clauses which pertained to the rights of the nobility. For our purposes the most important part of the document is the Security Clause. (read the entire text here) Magna Carta, Clause 61 The Security Clause “… the barons choose five and twenty barons of the kingdom, whomsoever they will, who shall be bound with all their might, to observe and hold, and cause to be observed, the peace and liberties we have granted and confirmed to them by this our present Charter …” “This established a committee of 25 barons who could at any time meet and overrule the will of the King, through force by seizing his castles and possessions if needed. This was based on a medieval legal practice known as distraint, but it was the first time it had been applied to a monarch. In addition, the King was to take an oath of loyalty to the committee.” This was the birth of a legislature with oversight authority over the executive branch. Parliament was able to attain control over the purse. Monarchs had to summon parliaments in order to get revenue. The fact that the king had to call Parliament in order to obtain revenue turned into the ability to present grievances to the King. Parliaments brought grievances before the king and demanded concessions before they would consider tax bills. But factors still existed which placed limits on parliamentary power. Parliaments were called and dissolved by the Monarch at their discretion. Often long periods of time might elapse between Parliaments. During these periods, the monarch could rule without limit. We will note that in the United States Constitution, the president has no authority over the summoning or adjourning of Congress. The mandate in our Constitution that Congress meets at least once every year is to enhance its independence from the executive. The actual powers of parliament took time to develop. It would take centuries to secure these powers, but the process begins at this point. Here are links that help outline the evolution of the British Parliament. Here is a full list of the Parliaments of England from 1236 – 1707. After 1707, it was called the Parliament of Great Britain, and after 1801 it was called the Parliament of the United Kingdom. A few links: List of Speakers of the House of Commons of England The House of Lords The House of Commons Until the British Bill of Rights wrote out the powers of the different governing institutions, power in England would fluctuate between the monarchy, the nobility and clergy, and shire and borough representatives. Here are a few critical periods in the development of the British Parliament. The purpose behind walking through this history is to understand the slow, steady evolution of legislative power. 1265: The Great Council The committee of 25 barons is enlarged in order to increase its strength. Members pulled from all over Britain, every burgher and shire. The council had to approve taxes requested by the King, but grew to demand a redress of grievances before it would do so. This was less a legislature than an advisory body for the king. 1295: The Model Parliament Called by Edward the First in 1295. The name was derived from parler, "to speak" "what touches all, should be approved of all, and it is also clear that common dangers should be met by measures agreed upon in common.“ The ability to discuss grievances in common was established. The monarch had control over who sat in Parliament. This is often considered to be the first parliament. It was composed of members of the nobility and clergy. Membership was due to one’s position in society. It’s authority still rested on the consent of the monarch. In 1322, the authority of Parliament was for the first time recognized not simply by custom or royal charter, but by an authoritative statute, passed by Parliament itself. It became an independent institution. It was still unicameral at that time, but it would begin to split in two. 1341: The House of Commons th 14 Develops in the Century during the reign of Edward III. Less powerful than the House of Lords. It acquires the powers to demand an accounting of royal spending, to question military actions, and to impeach the King’s ministers. “Parliament clearly separated into two distinct chambers: the House of Commons (consisting of the shire and borough representatives) and the House of Lords (consisting of the senior clergy and the nobility). The authority of Parliament continued to grow, and, during the early fifteenth century, both Houses exercised powers to an extent not seen before. The Lords were far more powerful than the Commons because of the great influence of the aristocrats and prelates of the realm.” – House of Lords “The House of Commons of the Kingdom of England evolved from an undivided parliament to serve as the voice of the tax-paying subjects of the counties and of the boroughs. Knights of the shire, elected from each county, were usually landowners, while the borough members were often from the merchant classes. These members represented subjects of the Crown who were not Lords Temporal or Spiritual, who themselves sat in the House of Lords. The House of Commons gained its name because it represented communities” – House of Commons Note that the Commons was developed to allow for the tax paying public to participate in government. This helps place the concern with “taxation without representation” in historical context. Membership in the House of Commons was open to property owners with no noble lineage. They were selected by communities whereas the monarch summoned members of the House of Lords. This is an important point, because as merchants become wealthier over the course of British history, they would become more powerful. The House of Commons would become the institutions that would help them convert economic power into political power. This is an important point. As the middle class gained wealth, they were able to increase the power of the House of Commons. It was the commons that would be principally responsible for reducing the power of the monarchy. Read up on the history here. 1376: The Good Parliament Called by Edward the III Forced reforms among the King’s counselors who were considered to be corrupt. 1404: Unlearned Parliament “the king refused to allow lawyers to stand as members, with "No Sheriff to be returned, nor any apprentice or other person at law" due to the King claiming that they were "troublesome", although more likely simply because they were familiar with the law.” The power of the nobility – and the House of Lords with it – is argued to have been a consequence of the War of the Roses (1455 – 1485). With their heavy casualties among the nobility, the wars are thought to have continued the changes in feudal English society caused by the effects of the Black Death, including a weakening of the feudal power of the nobles and a corresponding strengthening of the merchant classes, and the growth of a strong, centralized monarchy under the Tudors. – war of the roses. 1529: English Reformation Parliament “passed and enabled the major pieces of legislation leading to the English Reformation” This marked the transition of Britain from a Catholic to a Protestant (Anglican) country. It also put the state in charge of the official church. The monarch is the official head of the Anglican church. The most important changes to the relationship between Parliament and the monarchy occurred during the reign of the Stuart Monarchs. These are the four principle monarchs during this period. James I Charles I Charles II James II The Stuarts were strong supporters of the divine right of the king, and saw little legitimacy in Parliament. It was an inferior entity subject to the monarch’s rule. They also claimed the right to rule based on royal prerogative. They were also Scottish, so were viewed with suspicion by the British. And perhaps most critically, they either were or supported Catholicism, and opposed some of the more “radical” Protestant sects developing – especially the Puritans. Background: Catholicism, had (has) a more rigidly authoritarian structure and was seen as more conducive to absolutism than Protestantism, which tended to be more congregational. An affiliation with the Catholic Church was seen as supporting tyranny. James I ruled from 1603 – 1625 Called by a critic: “the wisest fool in Christendom.” He offered his own take on the power of the monarchy as opposed to Parliament. The True Law of Free Monarchies “Kings were the authors and makers of the laws, and not the laws of the kings. In the Parliament (which is nothing else but the head court of the king and his vassals) the laws are but craved by his subjects and only made by him at their rogation and with their advice. For albeit the king make daily statutes and ordinances, enjoining such pains thereto as he thinks meet, without any advice of Parliament or estates, yet it lies in the power of no Parliament to make any kind of law or statute without his scepter be to it, for giving it the force of a law.” – James I source. As a side note for now, he would also be responsible for issuing the charters sending a group of people across the Atlantic and authorizing them to settle a colony. The goal was to find new sources of revenue. The town they settled would be called Jamestown. James’ troubles with Parliament often involved money. The Stuarts devised means of gathering revenue without the approval of Parliament. 1614: Addled Parliament “sat between 5 April and 7 June 1614. Its name alludes to its ineffectiveness: it lasted no more than eight weeks and failed to resolve the conflict between the king, who wished to raise money in the form of a 'Benevolence', a grant of £65,000 and the House of Commons (who were resisting further taxation). It was dissolved by the king.” 1625: Useless Parliament The Useless Parliament was the first Parliament of England of the reign of King Charles I, sitting only from June until August 1625. It gained its name because it transacted no significant business, making it 'useless' from the king's point of view. Parliament adjourned to Oxford on 1 August, and was dissolved on 12 August, having offended the king. James I’s problems with Parliament were nothing compared to Charles I’s (1625-1649). His troubles would culminate in his execution and the temporary suspension of the monarchy (as well as the House of Lords) itself. Background: From 1414 until 1625, it had been customary at the beginning of each new monarch's reign for parliament to grant him or her the duties of tonnage and poundage for life. The parliament of 1625, the first of Charles I's reign, had broken with tradition by granting them for one year only. A major turn to the negative happened in 1628 when Charles was presented the Petition of Right which not only listed the king’s abuses, but argued that he was violating the “ancient rights and liberties” agreed to in the Magna Carta. The leading force behind the petition was Edward Coke, a leading legal scholar whose writing on the common law would influence the colonists. The Petition is argued to be, along with Magna Carta and the British Bill of Rights, the core of the British Constitution. In enacting the Petition, Parliament sought redress on the following points: Taxation without Parliament's consent Forced loans Arbitrary arrest Imprisonment contrary to Magna Carta Arbitrary interference with property rights Lack of enforcement of habeas corpus Forced billeting of troops Imposition of martial law Exemption of officials from due process We will later point out that these will be similar to complaints the colonists would have with Britain in 150 years. Charles responded by suspending Parliament and refusing to allow it to meet again for 11 years. He had unlimited control of government during those years. This was called the Eleven Year's Tyranny (16291640). It set in motion a series of events which would culminate in the execution of Charles 1st and the temporary abolition of the monarchy during the monarchy. Here is an overview of the rapid series of events that would follow. Timeline 1640: The Short Parliament 1640 – 1648: The Long Parliament. 1642 – 1651: The English Civil Wars. 1645-1660: The New Model Army 1648: Pride’s Purge. 1648 - 1653: The Rump Parliament. 1649: The Execution of Charles the First. 1649 – 1660: The Commonwealth of England. Timeline 1651: The Battle of Worcester 1653 – 1658: The Rule of Oliver Cromwell. 1660: The Restoration of the Monarchy. 1660 – 1685: Charles II rules. 1685 – 1688: James II rules. 1688: The Glorious Revolution. 1689: The English Bill of Rights signed. 1640: The Short Parliament Charles eventually had to call Parliament back in session to obtain money to pay for military conflicts, but Parliament wanted to air grievances prior to considering the request. Charles refused to do so and dissolved Parliament after three weeks. “The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The five members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.” The Long Parliament was called to deal with government funding following the Bishops’ War, where Charles supported an “episcopalian system of church government for Scotland (with bishops),” over “the desire of much of the polity of Scotland for a presbyterian system of governance (without bishops).” Again, Parliament wanted to deal with grievances prior to funding. They abolished the Star Chamber, and investigated many members of the King’s court, including the Queen. We will discuss the Star Chamber in depth when we discuss the Judiciary and the development of the concept of an independent judiciary. This led the King in 1642 to charge into Parliament to arrest the five members he thought were leading this effort. They had left and Speaker refused to tell him where they went. We’ll point out later that we can trace the prohibition against arresting members of Congress when they go to and from Congress on this event. This is part of the Constitution. The King left for Oxford along with members of Parliament who supported him to form a separate parliament. This led to the First English Civil War. Supporters of the King fought supporters of the Long Parliament. Parliament establishes the New Model Army, composed primarily of Puritans, in 1645 to effectively fight the war. They would remain in existence until 1660. Charles would be captured and defeated, but would engineer a come back. In the Second Civil War (1648 – 1649) royalists attempted to restore Charles, but were not only defeated, but led opponents in Parliament to move to execute Charles for high treason. Charles still had supporters in Parliament, so these were removed forcibly by Thomas Pride, in an event in 1649 called Pride’s Purge. Parliament shrunk from 507 to around 200. “This marked the end of the Long Parliament and the beginning of the Rump Parliament.” The remaining members would vote to try Charles on high treason and execute him. They would also establish a council of state to replace the monarchy and abolished the House of Lords. On 19 March 1649, the House of Lords was abolished by an Act of Parliament, which declared that "The Commons of England [find] by too long experience that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England."[7] The House of Lords did not assemble again until the Convention Parliament met in 1660 and the monarchy was restored. It returned to its former position as the more powerful chamber of Parliament—a position it would occupy until the 19th century. Several changes in government happened between 1649 and 1660 The entire period is referred to as the Interregnum. Britain went through a period where various proposals were made about what the governing system should look like. What follows is a section from the Wikipedia section on “Diggers.” “Government through the King's Privy Council was replaced with a new body called the Council of State, which due to fundamental disagreements within a weakened Parliament was dominated by the Army. Many people were active in politics, suggesting alternative forms of government to replace the old order. . . . . . These ranged from Royalists, who wished to place King Charles II on the throne; men like Oliver Cromwell, who wished to govern with a plutocratic Parliament voted in by an electorate based on property, similar to that which was enfranchised before the civil war . . . . . . agitators called Levellers, influenced by the writings of John Lilburne, who wanted parliamentary government based on an electorate of every male head of a household; Fifth Monarchy Men, who advocated a theocracy; and the Diggers led by Winstanley, who advocated a more radical solution.” Diggers - Wikipedia. This era in English history can be divided into four periods. 1 - The first period of the Commonwealth of England from 1649 until 1653 2 - The Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell from 1653 to 1658 3 - The Protectorate under Richard Cromwell from 1658 to 1659 4 - The second period of the Commonwealth of England from 1659 until 1660 The Rump Parliament would exercise both executive and legislative functions during the Commonwealth until 1653 when Oliver Cromwell forcibly dissolved it backed by troops. Like the Stuarts, Cromwell was frustrated by the ineffectiveness of Parliament. The Commonwealth was replaced with a Protectorate, with Cromwell as Lord Protector. He effectively became dictator. This is considered by historians to be a military coup. His power was never based on popular support, only on the military. He died in 1658 and was replaced with his son Richard who lacked his power. The Protectorate would crumble and the monarchy would be restored. Three things undermined the Protectorate: the "anxieties of the army, the irresponsibility of the Parliament and the rashness of Richard Cromwell"; what ultimately prevented the retention of the Protectorate was the opposition of the "junior officers" and "many of the common soldiers" There was no check on the legislature. The point was taken that unfettered legislative power can be as tyrannical as monarchic power. All governing power must be checked. Government was also unstable and chaotic during this era. So much so that Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan during this period. “Hobbes wrote that chaos or civil war — situations identified with a state of nature and the famous motto Bellum omnium contra omnes ("the war of all against all") — could only be averted by strong central government.” Support emerged for restoring the monarchy so that there could be more stability in society. The Convention Parliament of 1660 Summoned the King – James II – back to the throne. Oak Apple Day May 29 The day celebrated by royalists to commemorate the restoration of the monarchy. Some of the people responsible for the trial and execution of Charles were punished. Neat Trivia: Three Commissioners, John Dixwell, Edward Whalley and William Goffe, reunited in New Haven, Connecticut in 1661. All died natural deaths in the 1670s and are commemorated by three intersecting major avenues in New Haven (Dixwell Avenue, Whalley Avenue, and Goffe Street), and by place names in other Connecticut towns. But the restoration simply revived the conflict between the divine monarchy and the Parliament. Charles II did not want to share power with Parliament and he sought alternative ways of gaining revenue so he could become absolute monarch of England. “Following the English Restoration in 1660, King Charles II sought to streamline the administration of these colonial territories, beginning a process of bringing a number of the colonies under direct crown control.” – Dominion of New England. 1661 – 1679: Cavalier Parliament Dominated by Royalists. Passed legislation that enhanced monarchic power. Charles II was replaced with James II who became Catholic and whose monarchy was not universally accepted as legitimate. He also had a male heir – which terrified Parliament who thought this would lead to a reestablishment of Catholicism in the country. 1685 – 1688: Loyal Parliament Meet briefly during the monarchy of James II. The king influenced elections of many members of the Commons in order to ensure support. But they began questioning his efforts to enhance his control of a peacetime military and he was driven from office in the Glorious Revolution . James was driven from the crown – and England – in the Glorious Revolution. Which created a vacancy in the monarchy which the Parliament was able to fill. Convention Parliament (1689) The English Convention (1689) was an irregular assembly of the Parliament of England which transferred the Crowns of England and Ireland from James II to William III. It differed from the English Convention (1660) in that it did not unconditionally restore the rightful and lawful monarch, but chose to justify the deposing of that monarch in favour of another, and also sought to introduce new laws and arrangements into the constitution. These new arrangements were contained in the British Bill of Rights, which was a type of constitution. It defined the relationship between the legislature and the executive, and spelled out certain rights of the people. William and Mary had to sign the document in order to become monarchs. Once signed, England began the transition to a Parliamentary Democracy. The executive power would be contained. No more arbitrary rule. The document was heavily influenced by the previous 80 years history with the Stuarts. The manner in which the relationship between the three governing institutions was institutionalized in the English Bill of Rights would influence how this would be done in the U.S. Constitution. Some highlights. The document demanded that William and Mary acknowledge that certain actions of the previous rulers were illegal and were not to be repeated. The English Bill of Rights That the pretended power of suspending the laws or the execution of laws by regal authority without consent of Parliament is illegal; That levying money for or to the use of the Crown by pretence of prerogative, without grant of Parliament, for longer time, or in other manner than the same is or shall be granted, is illegal; That it is the right of the subjects to petition the king, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal; That the raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, unless it be with consent of Parliament, is against law; The English Bill of Rights That the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law; That the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament; That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted; Meanwhile across the Atlantic: By the time the British Bill of Rights was signed, the colonies had been able to govern themselves for 80 years. They had grown used to self rule. The revolution also led to the collapse of the Dominion of New England and the overthrow of Maryland's government. Once Britain’s internal issues were settled, they could focus on external issues. These would include disputes with the French and eventual attempts to control the North American Colonies. Colonial/US Congressional Timeline 1600s: Colonial Legislatures Established 1754: The Albany Congress 1765: The Stamp Act Congress 1774: The First Continental Congress 1775: The Second Continental Congress 1776: The Declaration of Independence 1781 – 1789: The Articles of Confederation The London Company (also called the Charter of the Virginia Company of London) was an English joint stock company established by royal charter by James I of England on April 10, 1606 with the purpose of establishing colonial settlements in North America. The first two charters issued for the colonies were corporate charters issued to the London and Plymouth Companies Competing land claims led many corporate colonies to change to royal charters. Colonial Government in the Thirteen Colonies. On July 30, 1619, the House of Burgesses, the first legislature of elected representatives in America, met in the Jamestown Church. Their first law was to set a minimum price for the sale of tobacco and set forth plans for the creation of the first ironworks of the colony. This legislative group was the predecessor of the modern Virginia General Assembly. The Virginia House of Burgess . . . the first assembly of elected representatives of English colonists in North America. The House was established by the Virginia Company, who created the body as part of an effort to encourage English craftsmen to settle in North America. Its first meeting was held in Jamestown, Virginia, on July 30, 1619. Here is the membership of the original council. “The Assemblies had a variety of titles, such as: House of Delegates, House of Burgesses, or Assembly of Freemen. They had several features in common. Members were elected by the propertied citizens of the towns or counties annually, which usually meant for a single, brief session, although the council or governor could and sometimes did call for a special session. Suffrage was restricted to free white men only, usually with property ownership restrictions. Since land ownership was widespread, most white men could vote. Taxes and government budgets originated in the Assembly. The budget was also connected with the raising and equipping of the militia. As the American Revolution grew nearer, this contributed to the conflict between the assembly and the governor.” Local government was conducted through town meetings. The virtue of self rule is argued to have evolved primarily from these institutions. From 1607 until the mid 1760s, the colonies were generally free to govern themselves. Aside from the internal disputes during the civil wars, the British had to compete with the French for control of North America. - Emergence of Colonial Government “Generally the term colonial legislature means a governing body of representatives selected to lead one of the original thirteen colonies. Sometimes they were selected by the residents of the colony as with the House of Burgesses in Virginia, other times they were selected by the British crown as in Georgia. They made laws for the colony, settled disputes, and organized how the economics of the colony were to be organized.” These various colonial legislatures impacted the United States Constitution in the following ways: 1. They established the principle of having a WRITTEN constitution. 2. They offered valuable experience for those men that would later participate in the Constitutional Convention held in Philadelphia in 1787. 3. They established the principle that the leaders of a colony were responsible to the PEOPLE of the colony. 4. They established the precedent of having a Bill of Rights added to their colonial constitutions thus giving the antifederalists the idea to add a Bill of Rights to the Constitution of the United States. 5. They established the precedent of having rotating leadership in which governors and state legislatures were re-elected (or voted out) every few years--this would also be incorporated in our federal constitution. Generally each legislature acted on its own an had its own unique relationship with the British government. They were jealous of their powers. There was an early attempt to coordinate activities between the colonies however. The attempt was driven by the emerging conflict with France that would culminate in the French and Indian Wars (1754 – 1763). Until the end of that conflict, Britain’s control of the North American colonies was tenuous. 1754: The Albany Congress A meeting of seven colonies to discuss issues of mutual concern and consider forming a confederation. English officials proposed establishing a "union between ye Royal, Proprietary & Charter Governments,“ in order to handle the strains war would place on the colonies. Under the Albany Plan “each colonial legislature would elect delegates to an American continental assembly presided over by a royal governor.” – Constitution.org. The colonies would have legislative power and the crown would have executive power. The plan would be rejected by the colonies and not sent to the crown for consideration. The crown did not like the idea that the colonies might join forces, the colonies distrusted each other and could not agree on a form of government acceptable to them all. They were concerned about losing autonomy. The design would influence the Congress created under the Articles of Confederation. In many ways, this conflict still exists to day over the proper role of the state and national government. Once the conflict was settled Britain acquired new lands to the west of the existing colonies. King George III passed the Royal Proclamation Act of 1763 to determine how best to govern the new territory, which some colonies claimed for themselves. New officers, representing Britain, would be sent to govern the new lands. Conflict, predictably, resulted. The new land that Britain took from France provided opportunities for the British to send over official and troops. As with previous historical episodes where the need for funds to pay off military debt drove conflict between the crown and Parliament, the need to pay off the debt from the French and Indian Wars drove the conflict between the British Parliament and the colonists. It provided a common event for all colonies to respond to and galvanize around. The institutional response was the establishment of a series of Congresses. Three noteworthy Congresses composed of delegates from each colony: The Stamp Act Congress The First Continental Congress The Second Continental Congress Note that these were not legislative institutions (the word Congress does not have the same meaning it has currently). They were assemblies where representatives can meet and discuss common issues. Within two years of the end of the French and Indian Wars, the Stamp Act was passed. The purpose of the tax was to help pay for troops stationed in North America after the British victory in the Seven Years' War. The British government felt that the colonies were the primary beneficiaries of this military presence, and should pay at least a portion of the expense. The imposition of the tax violated the sense of self government the colonist had grown used to. As a consequence The Stamp Act Congress was called. Representatives of nine colonies met to discuss the Stamp Act and to coordinate a response to it. They wrote the of Declaration of Rights and Grievances and sent it to Parliament. The Congress made the following claims (here’s a link to the document): - Only the colonial assemblies had a right to tax the colonies. (no taxation without representation). - Trial by jury was a right, and the use of Admiralty Courts was abusive. - Colonists possessed all the Rights of Englishmen. - Without voting rights, Parliament could not represent the colonists. Notice the similarity between their grievances and those made under the Petition of Right. In response – and because they could recognize a threat - The British began suspending colonial legislatures and developing ways to work around them. This would be a grievance listed in the Declaration of Independence. Colonists began regularly meeting – sometimes illegally. Committees of Correspondence effectively established shadow governments that would coordinate the activities of colonies leading up to the war. Committees of Correspondence. The Committee of Correspondence: Moving Towards Independence 1774: The First Continental Congress Met in response to the Coercive Acts, many issued in response to the Boston Tea Party. 1775: The Second Continental Congress Produced the Declaration of Independence, managed the Revolutionary War, and served as de facto government of the U.S. until the adoption of the Articles of Confederation in 1781. 1776: The Declaration of Independence Argued that King George was attempting to establish tyrannical control over the colonies and was therefore unfit to be the ruler of a free people. A principle argument made in the document was that the king of England was attempting to usurp colonial legislative power, in addition to colonial executive and judicial power. This would create a tyranny. A variety of grievances were listed to prove the accusation of usurpation. Most focus on efforts of the king to limit or control colonial legislative power. What follows is a list of the specific grievances made in the document. The Legislative Grievances in the Declaration of Independence • He has refused his assent to laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. • He has forbidden his governors to pass laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his assent should be obtained; and, when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. • He has refused to pass other laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of representation in the legislature, a right inestimable to them, and formidable to tyrants only. • He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. The Legislative Grievances in the Declaration of Independence • He has dissolved representative houses repeatedly, for opposing, with manly firmness, his invasions on the rights of the people. • He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise; the state remaining, in the mean time, exposed to all the dangers of invasions from without and convulsions within. • He has endeavored to prevent the population of these states; for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migration hither, and raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands. • He has obstructed the administration of justice, by refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers. The Legislative Grievances in the Declaration of Independence • He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution and unacknowledged by our laws, giving his assent to their acts of pretended legislation: • For imposing taxes on us without our consent; • For abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province, establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging its boundaries, so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these colonies; • For taking away our charters, abolishing our most valuable laws, and altering fundamentally the forms of our governments; • For suspending our own legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. Collectively these prove the importance of independent legislatures and self government. They also provide hints about what types of design features a legislature should have. Fear of national executive and judicial power explains why the Articles of Confederation only created a national legislature, called the Continental Congress, with delegates closely connected to the states. Until the Ratification of the Articles of Confederation the Second Continental Congress served as the Congress of the United States. “The Congress had no authority to levy taxes, and was required to request money, supplies, and troops from the states to support the war effort. Individual states frequently ignored these requests.” It had no direct connection with the general population – which was the course of sovereign authority. This was also true for the Congress under the Articles of Confederation. We will notice in the next section that the House of Representative is designed to have a direct connection with the general population, and that this is the source of the nation’s legitimacy. The Articles of Confederation. Congress under the Articles of Confederation. The following parts of the Articles of Confederation outline the form of the legislature. The Continental Congress • Article V. For the most convenient management of the general interests of the United States, delegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislatures of each State shall direct, to meet in Congress on the first Monday in November, in every year, with a power reserved to each State to recall its delegates, or any of them, at any time within the year, and to send others in their stead for the remainder of the year. • No State shall be represented in Congress by less than two, nor more than seven members; and no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years; nor shall any person, being a delegate, be capable of holding any office under the United States, for which he, or another for his benefit, receives any salary, fees or emolument of any kind. The Continental Congress • Each State shall maintain its own delegates in a meeting of the States, and while they act as members of the committee of the States. • In determining questions in the United States in Congress assembled, each State shall have one vote. • Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Congress, and the members of Congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests or imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendance on Congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace. Key design features within this document weaken the legislature. One year terms Delegates serve as teams Delegates can be recalled and replaced at any time. Note that some of the language is similar to what is in the British Bill of Rights. The Federalists complained about the inability of the governing system to achieve national goals and sought to create a stronger legislature independent of the states. Anti-Federalists liked the fact that government was directly tied into the needs of the electorate and did not see a lack of coordination between the states as a significant problem. Constitutional Convention would provide the forum where these disputes could be addressed and ironed out. This will be covered in the next section. You can stop here. I’ll build off the following slides at some point in the near future. A few general points about the evolution of state legislatures, and the Texas Legislature, before we conclude. Links: Wikipedia: State Legislatures National Conference of State Legislatures. Thomas: State Legislature Websites. Congress of the Republic of Texas TSHA Website There was no self rule – beyond local governance – in Texas prior to Mexican independence from Spain. After the 1821 revolution and the 1824 ratification of the Mexican Constitution (and the decision to become a federal republic) , Texas was given the option of becoming a Mexican state. For a period of time Texas was the northern district of the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Texas felt underrepresented in the state legislature. It had 2 out of 12 members. As the number of Americans moving into Texas increased, tensions increased as well, many centered on the Mexican government’s decision to abolish slavery.