Asian-Canadians (Jason, David, Graham) - History

advertisement

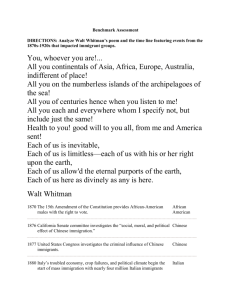

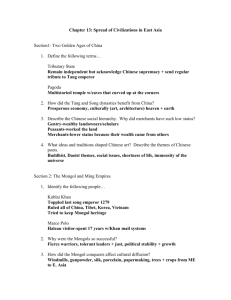

Asian Canadians in the Century JASON VAZ GRAHAM LEE DAVE SMITH th 20 South Asian Canadians JASON VAZ 1900: The first recorded entry of South Asians (SA) into Canada. Upper middleclass farming families sent a capable member to Canada to alleviate heavy monetary debts owed to dishonest landowners in the state of Punjab. At this time, British Columbian farmers were looking for man-power to till acres of unused yet farmable soil, and they advertised Canada as the land of opportunity. In response, 5000 SA Sikh farmers arrived over a period of 7 years. Since the dominion government imposed a $500 charge on any Chinese that wished to enter Canada, most BC farmers looked for SA and Japanese help. <- Indian immigrant workers in a British Columbian lumber mill in 1905. 1907: The British Columbia race riots The BC race riots were a reaction to the tension of (1) escalating unemployment of indigenous farmers, which would eventually lead to depression the following year, and (2) increasing arrivals of the SA “menace” to BC in search of work. The BritishCanadian Government, in reaction to these riots imposed strictures unreasonable restrictions on SA immigrants, which forced many of them to flee back to India. The British Government tried to send the remaining 1,100 SA immigrants to British-Honduras from where most of them returned due to inhabitable conditions. In British Columbia, the returning SAs were allowed to stay but were not permitted to bring their families from India to live with them. Indians helped to build the Western Pacific Railroad lines, completed in 1909 1919: The Government allows SA immigrants to bring their families to Canada. The Government allowed “legal SA residents” to bring their wives and dependent children to Canada. The illegal SA residents were those that entered the country between 1908 and 1918 like the the SAs on board Komagata Maru in 1914. Left: A Sikh family in B.C., 1920. Below: passengers on board the Komagata Maru, 1914 1947: Voting rights are awarded to SAs by the BC government. This was brought about by the combined lobbying of local SAs and provincial officials. The Government agreed because it could no longer hold on to prejudicial restrictions and justify it after the Second World War. 1967: Race, ethnicity and nationality disregarded by Canadian Government in immigrant selection Recognizing the economic benefits of immigrants and the growing need to strengthen the Canada’s economy and man-power, immigrants were now selected on economic criteria and skill type/ level. <- The multicultural staff working for the Toronto and Region Conservation Society (TRCS). Image sources http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/SSEAL/echoes/toc.html http://www.google.ca/imgres?imgurl=http://www.frw.ca/alb ums/TRCA/TRCA_and_FRW_staff_join_Councillor_Cho_at _Multicultural_Project_Site_in_MorningsideTributary.jpg&i mgrefurl=http://www.frw.ca/rouge.php%3FID%3D124&usg= __MMyq8gMXw_JHnxyFa7ezkkA1cpc=&h=360&w=480&sz =31&hl=en&start=28&zoom=1&tbnid=YfTPCFoV70UarM:&t bnh=150&tbnw=258&ei=kaE4TfbaB5KGhQeStdXOCg&prev= /images%3Fq%3Dmulticultural%2Btoronto%2Bcanada%26u m%3D1%26hl%3Den%26biw%3D1639%26bih%3D800%26tb s%3Disch:10,600&um=1&itbs=1&iact=hc&vpx=360&vpy=22 6&dur=306&hovh=192&hovw=258&tx=223&ty=110&oei=h6 E4TbbDCsvPgAfix9CxCA&esq=2&page=2&ndsp=29&ved=1t: 429,r:1,s:28&biw=1639&bih=800 Chinese Canadians GRAHAM LEE September, 1907: Anti-Chinese Riot in Vancouver In September of 1907, 8000 whites enter Vancouver’s Chinatown, smash windows and doors, and hurl rocks. They cause thousands of dollars of damage. Terrified residents arm themselves with guns and clubs in preparation for further attacks (which are prevented on the next day by Vancouver police). Vancouver Chinatown, the day after the riot. The windows and doors of the shops have been boarded up. Source: Portraits of a Challenge, 119. Although not the only incident of widespread white rioting directed towards Chinese Canadians at the time, it is indicative of the violent hostility they face in Canadian cities that had been their homes, sometimes for decades. It is also the largest example of this type of violence. With a population of 3600, Vancouver’s Chinatown is the largest in the country at the time. (Chinatown, 42) July 1, 1923: Chinese Immigration Act Many Chinese Canadians know this act as the Chinese Exclusion Act. It comes into law on “Dominion Day” (Canada Day), which the Chinese community promptly dubs “Humiliation Day” in protest. The act bans all immigration from China for the next 24 years. It is especially damaging for Chinese communities that are comprised primarily of male labourers, who had come to Canada to find work and to earn enough money to eventually bring their families over to join them. The act creates isolated communities, and even a gradual decline in some Chinese Canadian populations. Men are left without companionship or family. Some of the “ills” that become associated with Chinatowns in later years, such as gambling dens, are the direct result of this gender imbalance and the lack of viable leisure alternatives for the inhabitants. Historical Cartoon depicting the differing immigration policies of the time. Source: Portraits of a Challenge, 126. The act is an escalation of the previous Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, which had already imposed a head tax on all Chinese immigrants. May 14, 1947: Chinese Immigration Act Repealed Because Chinese-Canadians played an important role in wartime fundraising, joined the armed forces, and served as secret agents in the Pacific, hostilities between them and white Canadians are lessened. On top of this, the post-Nazi understanding of the dangers of racial crimes, the recently ratified UN Charter, and the Canadian Citizenship Act of 1946, help set a tone of increased human rights and racial tolerance in the country. The culmination of these changes is the repealing of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923. The official repealing of the Immigration Act of 1923. Source: Portraits of a Challenge, 160 Chinese-Canadians are given full citizenship rights in 1947, including the right to vote. Chinese immigration remains limited, but the spouses and dependents of Chinese-Canadians are allowed into the country. The isolated, predominantly male Chinatowns are transformed into more balanced and complete communities. 1967: Immigration Reform The thriving Vancouver Chinatown of the 1960s. Source: Chinatown, 48. The Canadian immigration system is reformed. The race and “place of origin” section of the immigration policy are removed and the point system is adopted. With these changes, independent Chinese immigration begins, and the family reunification policy continues. The Chinese Canadian population more than doubles in the next decade, and the type of immigrant also changes. (Struggle and Hope, 51) Now wealthier, educated immigrants and skilled workers are also entering the country. Chinatowns, which had been impoverished and decaying until this point, are revitalized by a fresh influx of capital. Also, many Chinese Canadians move beyond Chinatowns and take up residence in traditionally white neighbourhoods. September 1979: “Campus Giveaway” on CTV With high levels of Chinese immigration continuing, tensions rise again. Since 1975 more than 60000 Chinese refugees have fled Vietnam and Cambodia and settled in Canada. (Struggle and Hope, 62) This is in addition to the other immigrants already entering the country. Chinese Canadian protestors reacting to the “Campus Giveaway” show on CTV Source: Chinese Canadian National Council. Chinese Canadian Historical Photos Exhibit http://www.ccnc.ca/toronto/history/pgallery.html In the fall of 1979, the CTV program W-5 runs a report entitled “Campus Giveaway” that alleges that foreign students are taking places from Canadian students at universities. It uses footage of Canadian born, ethnically Chinese students in a pharmacy class, and implies that they are foreign students. Subsequent investigations prove that there were no foreign students in the class, and that many of the numbers in the report were wildly inaccurate. The report is seen by many Chinese-Canadians as symptomatic of the media’s hostility, and its inflammatory use of “Asian Invasion” rhetoric. They also resent the fact that even when born in the country they are represented as “foreign.” Widespread protests eventually force an unconditional apology and retraction from CTV. Protestors in Toronto also form the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) to combat such issues in the future. Works Cited Images Chinese Canadian National Council. Chinese Canadian Historical Photo Exhibit. http://www.ccnc.ca/toronto/history/pgallery.html Lee, Wai-man. Portraits of a Challenge: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Canadians. Toronto: Council of Chinese Canadians in Ontario, 1984. Text Yee, Paul. Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., 2005. Yee, Paul. Struggle and Hope: The Story of Chinese Canadians. Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1996. Japanese Canadians DAVID SMITH 1908: Hayashi-Lemieux “Gentleman’s Agreement” Following the 1907 Vancouver riot against Asian residents, in response to growing anti-Asian sentiment in B.C., Minister of Labour Rodolphe Lemieux meets with Japanese Foreign Minister Tadasu Hayashi to limit the number of Japanese labourers and domestic servants arriving in Canada. Though Japanese citizens are allowed to travel and settle in any part of the British Dominion (and are guaranteed protection of their private property), the two ministers agree that something must be done in response to the riot. Thus, a quota of 400 is set on the number of Japanese allowed to emigrate from Japan to Canada. Although no treaty is ever signed, a significant drop in immigration from Japan occurs from the nearly 8000 Japanese who enter Canada in 1908 to just under 500 the following year. Japanese immigrants on the pier in Vancouver, 1908. Source: “n1908.” 2007. Virtual Museum of Canada. Web. 20 January 2011. One notable exemption to this quota is wives of those already living in Canada, giving rise to the phenomenon of “picture brides” – Japanese women who come to Canada after being wed to Canadian-Japanese men by proxy in Japan. In 1924 the agreement is amended to limit the quota to 150. December 7, 1941: Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong Attacked In response to the Japanese attacks on American and British naval bases in the Pacific, Canada declares war on Japan and institutes the War Measures Act. Japanese-Canadians’ boats are impounded and Japanese-Canadian schools are closed. Japanese nationals, along with Germans and Italians, are required to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens. Unlike Germans and Italians, Canadian citizens of Japanese origin are required to register as well. Winter in the Tashme, B.C. internment camp. Source: “3_4.” 2008. Sedai: The Japanese Canadian Legacy Project. Web. 20 January 2011. A “zone of defense” is established. All Japanese and Japanese Canadians (approx. 22,000 total) are required to exit the zone and move eastward. Seventy-five percent of those moved are Canadian citizens. Many are moved to B.C. ghost towns and internment camps, while others work on farms and in industries across the country. Objectors are interned in Ontario POW camps. Many of those interned lose their property, which has been confiscated and sold below value by the government to pay for the cost of maintaining the camps. September 2, 1945: Japan Surrenders The mushroom cloud from the five-tonne “Little Boy” atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Source: “_41358423_cloud_hirosh203.” 1 November 2007. BBC News. Web. 20 January 2011. As the war officially comes to a close following the August bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese internment camps are closed. Despite Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s admission that there was no evidence of wartime JapaneseCanadian sabotage or disloyalty, the interned Japanese Canadians are not allowed to return to British Columbia. Influenced by the intense racism and animosity of the B.C. provincial government toward the relocated Japanese Canadians, the federal government insists that the “loyal” Japanese citizens be distinguished from the “disloyal” and that the latter be repatriated to Japan. The Japanese were faced with an ultimatum: move east or leave. Eventually, about 4,000 chose deportation, roughly half of whom were native to Canada and had never before set foot in what was now a war-torn and impoverished Japan. March 31, 1949: Full franchise granted to Japanese Canadians Japanese Canadian citizen exercising her right to vote for the first time. Source: “b05_large.” 2003. 5 Generations. Web. 20 January 2011. It is not until March 31, 1949 that the last of the restrictions imposed on Japanese Canadians by the War Measures Act is finally removed. The B.C. provincial legislature grants them the right to vote at the provincial level – the federal franchise having been granted the previous year. They are now free to obtain jobs in the public domain, serve on juries, hold public office, and study and practise law. Japanese Canadians are now permitted to move and settle freely throughout the country, including resettlement in B.C. Few, however, choose to return, having already begun new lives in Central and Eastern Canada and having been stripped of their homes and property by the Custodian of Enemy Property during the war. September 22, 1988: Redress Agreement Signed After several years of lobbying by the National Association of Japanese Canadians and a similar bill passing in the US, Ottawa agrees to redress the wrongs done to Japanese Canadians under the Wartime Measures Act. The federal government acknowledges its wrongdoing and agrees to compensate those affected with $21,000 each, as well as $12 million to the Japanese Canadian community for educational and social programs, and $24 million to establish a joint Canadian Race Relations Foundation to combat racism. In addition, the War Measures Act is amended to prevent similar occurrences in the future, all criminal records relating to War Measures offences are cleared, and citizenship is restored to Japanese exiles. NAJC President Art Miki shaking hands with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney at the signing of the Redress Agreement. Source: “muloney.” 2008. NAJC. Web. 20 January 2011.