literary devices and rhetorical strategies 2013

advertisement

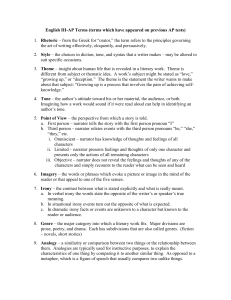

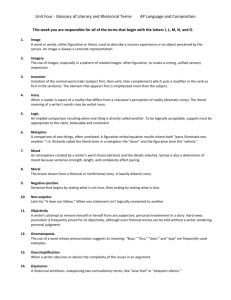

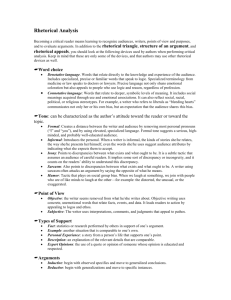

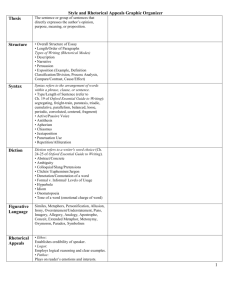

A work’s controlling idea, the main issue the work addresses. Most extensive literary analyses address theme, but should focus on the methods by which the author conveys the theme Avoid simply examining a common theme in all works; rather, examine how the writer conveys the theme in each work Series of events that occurs in a work › Exposition › Rising action › Climax › Falling Action › Resolution Time and place in which events unfold Sometimes setting must be inferred from details in the text. Other times authors state setting details directly at the beginning of a section. The mood or feeling of a work of literature created by details of setting or action › For example, a dark, cold or rainy day creates a gloomy and perhaps even scary atmosphere, but a story set in a sunny beach community might suggest a light mood. › Think about movies . . . The way an author develops an individual in a work A struggle between individuals, between an individual and a social or environmental force, or within an individual Hints, within the work, or events to come Short, vivid description that creates strong sensory impressions and that appeals to the senses the repetition of the initial consonant sounds in a group of words For example, in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” one line reads, “While I nodded, nearly napping. . .” Repetition of vowel sounds Ex: the “a” sound in “mad as a hatter” an indirect reference to another idea, person, place, event, artwork, etc. to enhance the meaning of the work in which it appears For example, if a writer were to refer to the mark of Cain, he would be making a biblical allusion to the story of Cain and Abel. a comparison between two different items that an author may use to describe, define, explain, etc. by indicating their similarities For example, Gary Soto’s A Summer Life reads, “The asphalt softened, the lawns grew spidery brown, and the dogs crept like shadows.” There are two analogies in this line: the lawns compared to spiders and the way dogs walk compared to shadows. two opposing ideas presented in a parallel manner For example, the opening of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities reads, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness. . .” How about this statement from Alexander Pope? “To err is human, to forgive, divine.” a device or figure of speech that is most frequently found in poetry. It is when a writer speaks directly to an abstract person, idea, or ideal. It is used to exhibit strong emotions. For example, Yeats wrote, “Be with me Beauty, for the fire is dying.” Shakespeare wrote, “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks.” an adjective or adjective phrase that an author uses to describe the perceived nature of a noun by accentuating one of its dominant characteristics, whether real or metaphorical For example, in Homer’s The Iliad, Athena is referred to as “grey-eyed Athena.” Sports figures are also often referenced by a dominant trait, such as Wilt the Stilt Chamberlain, Broadway Joe Namath, Mean Joe Greene, and Air Jordan. exaggeration or overstatement to emphasize a point or to achieve a specific effect that can be serious, humorous, sarcastic, or even ironic For example, calling a sports team unbeatable or a coach immortal is using hyperbole. Another example comes from Robert Burns’s emphasis of the depth of his love when he says it will last “until all the seas run dry.” the opposite of hyperbole. This is when a writer wishes to minimize the obvious importance or seriousness of someone or something, assuming that the audience knows the subject’s significance. An example would be when a firefighter says, “Just doing my job.” Another example would be when someone writes a letter to the editor opposing the building of a theater next to a school and instead of calling his opponents “hedonistic heathens,” he calls them “theater lovers.” a special type of understatement that is used for emphasis or affirmation. It asserts a point by denying the opposite For example, “Tornadoes are not unheard of in Nebraska during the summer.” “Our family did not fail to have its usual tension-filled vacation,” is another example. a direct comparison between two things For example, when Longfellow stated, “Thine eyes are stars of morning,” he was using a metaphor. an indirect comparison of two things using like, as, than, or resembles An example of this comes from Isaac Bashevis Singer. “The short story is like a room to be furnished; the novel is like a warehouse.” a metaphor in which the actual subject is represented by another thing that is related to it or emblematic of it An example of this follows: “The pen is mightier than the sword.” The idea here is that pen represents words or writing and sword stands for violence or war. a metaphor that uses a part to represent the whole or vice versa Referring to the congregation as “the church” or a complete vehicle as my “wheels” “In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than mine, will rest the final success of failure of our course.” John F. Kennedy a word that imitates the sound that is being made Examples include buzz, sizzle, lisp, murmur, hiss, roar, splat, whisper, and bang. a paradoxical image created by using two contradictory terms together Examples include bittersweet, jumbo shrimp, and pretty ugly. Another example is when Jonathan Swift wrote, “I do make humbly bold to present them with a short account. . .” a metaphor that gives human attributes to subjects that are nonhuman, abstract, and/or without life An example would be love is blind. Another example comes from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet when Romeo says, “Arise fair sun, and kill the envious moon/ Who is already sick and pale with grief. . .” When a writer employs grammatically similar constructions to create a sense of balance that allow the audience to compare and contrast the parallel subjects These constructions can be words, phrases, clauses, sentences, paragraphs, and whole sections or a longer work. In his speech delivered in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. used parallel structure by beginning each major paragraph with “I have a dream that. . .” When a writer poses a question to an audience and does not expect an answer or does not intend to provide one For example, Ernest Dowson asks, “Where are they now, the days of wine and roses?” Advertising uses rhetorical questions, as well: “Got milk?” a construction (word, phrase, another sentence) that is placed as an unexpected aside in the middle of the rest of the sentence This can be done either by parenthesis or by dashes. For example, “If you pick up the kids by 5:00 (by the way, you’re a dear for doing this) we can all meet for dinner at the Clubhouse Restaurant.” how, when, where, and how often you use rhetorical devices Examples include diction, syntax, tone or attitude, point of view, and organization. Also called word choice, it is the conscious decision the author makes when choosing vocabulary to create an intended effect. Some words used to describe diction are formal, informal, poetic, heightened, pretentious, slang, colloquial, ordinary, simple, complex, etc. Knowing your audience and purpose is essential to diction. the grammatical structure of sentences This is the careful choosing of sentence structure for variety to develop the subject, purpose, and/or effect. To discuss syntax you must have a working knowledge of these basic terms: phrases, main clauses, subordinate clauses, declarative sentence, imperative sentence, exclamatory sentence, interrogative sentence, simple sentence, compound sentence, complex sentence, compound-complex sentence, loose sentence, periodic sentence, inverted sentence, paragraphing, punctuation, and spelling. an author’s perception about a subject and its presentation to an audience Generally speaking, tone can be divided into three categories: informal, semiformal, and very formal. used in everyday writing and speaking and in informal writing It includes slang, colloquialisms, and regional expressions. is what students use in assigned essays for their classes They include standard vocabulary, conventional sentence structure, and few to no contractions. is what you would find in a professional scholarly journal or paper presented in an academic conference In this you may find polysyllabic words, professional jargon, and complex syntax that you would not use in ordinary conversations or informal writing. bitter sardonic objective idyllic naïve compassionate sarcastic ironic mocking scornful satiric indifferent scathing confidential factual informal facetious critical resigned joyous whimsical wistful nostalgic humorous astonished pedantic didactic inspiring remorseful disdainful laudatory mystified reverent lugubrious elegiac gothic macabre reflective maudlin sentimental patriotic admiring detached angry sad A discrepancy or incongruity of some kind › Verbal irony: discrepancy between literal words and what is actually meant (sarcasm is an example; ministry names in 1984) › Dramatic irony: discrepancy between what the speaker says and what the author means or what the audience knows (audience knows Juliet is just sleeping when Romeo laments her death) › Situational irony: the outcome is contradictory to what is expected (surprise endings) Vice or folly, with the purpose of developing awareness and perhaps even bringing reform Using wit and irony to attack absurdity and injustice An object, place, characteristic, or phenomenon that suggests one or more things, often abstract A recurring word, phrase, image, figure of speech, or symbol that has significance Ex: Use of blood and sleeplessness in The Tragedy of Macbeth the way an author presents ideas to an audience Some organization patters that are most often used are chronological cause/effect spatial contrast/comparison least to most important general to specific specific to general most important to least flashback/fast forward the method the writer uses to narrate the story First person is when the narrator is the main character of the tale. Third person objective is when the narrator is an uninvolved reporter. Third person omniscient is when the narrator is an allknowing onlooker who tells the reader what the character is thinking, gives background information, and provides material unknown to the characters. Stream-of-consciousness is when the reader is placed in the mind of the character and is privy to all his random or spontaneous thoughts. Interior monologue is a type of stream-of-consciousness that lets the reader in on a character’s on-going thoughts, perception, or commentary about a particular subject. Individual in the work who relates the story Not the same as the author the unique way an author consistently presents ideas. Authors’ choices of diction, syntax, imagery, rhetorical devices, structure, and content all contribute to a particular style.