Transparency at the Federal Reserve

advertisement

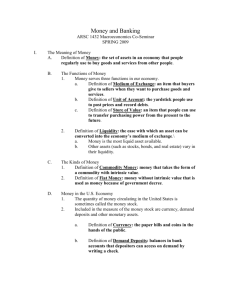

Transparency at the Federal Reserve: The Discount Window Background: The discount rate is the interest rate charged to commercial banks and other depository institutions on loans they receive from their regional Federal Reserve Bank's lending facility--the discount window. The Federal Reserve Banks offer three discount window programs to depository institutions: primary credit, secondary credit, and seasonal credit, each with its own interest rate. All discount window loans are fully secured. The following types of assets are most commonly pledged to secure discount window advances: • Obligations of the United States Treasury • Obligations of U.S. government agencies and government sponsored enterprises • Obligations of states or political subdivisions of the U.S. • Collateralized mortgage obligations • Asset-backed securities • Corporate bonds • Money market instruments • Residential real estate loans • Commercial, industrial, or agricultural loans • Commercial real estate loans • Consumer loans Under the primary credit program, loans are extended for a very short term (usually overnight) to depository institutions in generally sound financial condition. Depository institutions that are not eligible for primary credit may apply for secondary credit to meet short-term liquidity needs or to resolve severe financial difficulties. Seasonal credit is extended to relatively small depository institutions that have recurring intra-year fluctuations in funding needs, such as banks in agricultural or seasonal resort communities. Current Interest Rates Primary Credit 0.75% Secondary Credit 1.25% Seasonal Credit 0.20% Fed Funds Target 0 - 0.25% The discount rate charged for primary credit (the primary credit rate) is set above the usual level of short-term market interest rates. (Because primary credit is the Federal Reserve's main discount window program, the Federal Reserve at times uses the term "discount rate" to mean the primary credit rate.) The discount rate on secondary credit is above the rate on primary credit. The discount rate for seasonal credit is an average of selected market rates. Discount rates are established by each Reserve Bank's board of directors, subject to the review and determination of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The discount rates for the three lending programs are the same across all Reserve Banks except on days around a change in the rate. The following is discount borrowing information supplied by the Federal Reserve (1) How do financial institutions request an advance from the Discount Window? Requesting an advance requires a simple phone call to your Reserve Bank. Please be prepared to supply the following information: Name and location (city and state) of your institution. Your institution's ABA and telephone number. Page | 1 Your name and title. If your institution's borrowing resolution requires that two people request a Discount Window loan, please have a second authorized individual available. The type of credit you are requesting. The amount of the advance you are requesting. The number of days that funds will be needed. Discount Window staff may request additional information. Type of Credit Primary Credit - No questions asked. Secondary Credit - Additional information regarding the financial condition of the institution and the reason for borrowing may be necessary to complete the request. Seasonal Credit - Institution must have an approved seasonal line of credit. (2) Who is authorized to borrow? Your institution must specify who is authorized to borrow funds in the legal agreements submitted for access to the Discount Window. The Authorizing Resolution for Borrowers and the Signature Card (when applicable) contain the names of the individual(s) that are authorized. In some cases more than one person is required to authorize an advance. (3) How long can you borrow for? Primary credit is extended on a very short-term basis, usually overnight. It may also be extended for up to a few weeks to depository institutions in generally sound financial condition that cannot obtain temporary funds in the market at reasonable terms; normally these are small institutions. Longer-term extensions of credit are subject to increased administration. Secondary credit is extended on a very short-term basis, usually overnight. It may also be extended for a longer term if such credit would facilitate a timely return to reliance on market funding or the orderly resolution of a failing institution, subject to statutory requirements (FDICIA restrictions). Under the seasonal program, borrowers may obtain longer-term funds from the Discount Window during periods of seasonal need so they can carry fewer liquid assets during the rest of the year and make more funds available for local lending. A seasonal line is granted for a period of up to nine months. However, advances will mature on a monthly basis. (4) How is borrowing repaid? An advance is issued with a stated maturity date. Discount Window loans must be repaid on the maturity date or, at the lending Reserve Bank's discretion, upon demand. Repayment of principal and accrued interest is charged to the account to which the loan was posted. Multi-day advances, however, can be prepaid in whole or Page | 2 Fed to Name Banks That Borrowed From Discount Window Bloomberg.com March 31, 2011 For most of its 98-year history, the Federal Reserve has operated with all the transparency and enthusiasm for change of the Vatican. Now the ultra-secretive Fed is starting to change its ways, if somewhat grudgingly. Some of the new openness, such as Chairman Ben S. Bernanke’s plan for quarterly press briefings, is the central bank’s idea. Much of it comes under duress. Today, the Fed is set to disclose which banks borrowed from its discount window during the darkest moments of the 2008-09 financial crisis. This unprecedented view of the emergency loans the Fed extended to hundreds of banks is the result of a March 21 Supreme Court decision that left intact lower court rulings ordering disclosure in lawsuits filed by Bloomberg LP, parent of Bloomberg News, and News Corp.’s Fox News Network. Still, the Fed won’t disclose the collateral it accepted, which would reveal the risks it took. Future discount window borrowings will be made public, though only after a two-year delay, thanks to the new Dodd-Frank financial reform law. Given the prominent role the world’s biggest banks played in causing financial losses worldwide, largely because of what investors didn’t know or didn’t understand, some say the loans should be made public at once, Bloomberg Business week reports in its April 4 issue. Only then, the reasoning goes, would investors and counterparties of a Fed borrower be able to manage their own risks. “The free-market system only works if it’s fully informed,” says Lynn E. Turner, who battled the Fed over disclosure issues while serving as the Securities and Exchange Commission’s chief accountant from 1998 to 2001. “There’s a lot of similarity between the Fed and an SUV with blacked-out windows.” Core Function The Fed says such calls threaten its core function: preserving market confidence by acting as a lender of last resort. Publicizing the names of discount-window borrowers could spark bank runs or discourage sick banks from seeking help until they are fatally compromised. “The full monty may not be a good thing,” says Frederic Mishkin, a former Fed governor. For the Fed, keeping information from investors is nothing new. Congress last year had to pry loose the details of $3.3 trillion worth of crisis-fighting programs that relied on the central bank’s vault. In the late 1990s, the Fed successfully resisted the SEC’s attempt to require banks to stop using hidden funds, or “cookie jar reserves,” to smooth quarterly earnings, says Turner. Oldest Channel The discount window is the Fed’s oldest lending channel and traditionally its most secretive. Banks have been free to use it without publicly revealing the fact since the Fed’s 1913 birth. Loan demand varies, depending on market conditions and seasonal factors. In January 2007, before the financial crisis erupted, banks owed the Fed just $1.3 billion for discountwindow loans. By October 2008 borrowings peaked at $111 billion. One bank, Chicago-based Park National, owed the Fed $345 million before regulators shut it down in October 2009, according to data Page | 3 gleaned from a Freedom of Information Act request. The most recent data, for March 23, show banks owing just $13 million. Some former Fed insiders say the public should routinely be clued in when private institutions tap the public purse, in the same way the SEC requires companies to inform investors of major financial events. “This should be material information. Investors should have the right to know,” says Roberto Perli, a former Fed board economist who is managing director of International Strategy & Investment in Washington. Banks Reluctant Banks traditionally have been reluctant to use the window, fearing that savvy investors could tell by following clues in Fed loan data and market activity. In 2003 the Fed said banks would no longer have to show an inability to raise private funds to tap the discount window, hoping to end the stigma. But when the initial wave of distress swept the financial industry in 2007, banks still shied away. “We had no luck in encouraging banks to use the window,” says Donald Kohn, a Fed vice chairman at the time. During the worst of the financial crisis, banks paid extra to borrow to avoid the discount window’s taint by participating in a new Fed program, the Term Auction Facility. That allowed them to bypass the window and still get emergency money by bidding for it in group auctions. At its March 2009 peak, TAF provided banks with $493 billion in short-term credit--more than four times the highest volume of discount window lending, which occurred five months earlier. Press Briefings Today’s Fed is undeniably more open. Until 1994 the central bank didn’t even publicly disclose when it changed the benchmark lending rate, leaving the market to figure that out for itself. Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan cultivated an image as an oracle who delighted in obscuring rather than explaining. Today, interest rate changes are announced in public statements after the policy making Federal Open Market Committee meets. Presidents of regional Fed banks give dueling public speeches on monetary policy. Bernanke has even taken “60 Minutes” on a tour of his Dillon, South Carolina, home town. The chairman’s plans for quarterly press briefings beginning April 27 mark a further evolution in the Fed’s public outreach. With its profile higher than ever, demands for greater accountability will only continue. William Greider, author of the 1989 Fed history “Secrets of the Temple,” says the bank is losing the battle to maintain its mystique. “What has happened in the last three years is the mask has been torn away from the central bank,” he says. “And they can’t put it back on.” Page | 4 Fed Releases Discount-Window Loan Records under Order Bloomberg.com March 31, 2011 The Federal Reserve released thousands of pages of secret loan documents under court order, almost three years after Bloomberg LP first requested details of the central bank’s unprecedented support to banks during the financial crisis. The records reveal for the first time the names of financial institutions that borrowed directly from the central bank through the so-called discount window. The Fed provided the documents after the U.S. Supreme Court this month rejected a banking industry group’s attempt to shield them from public view. “This is an enormous breakthrough in the public interest,” said Walker Todd, a former Cleveland Fed attorney who has written research on the Fed lending facility. “They have long wanted to keep the discount window confidential. They have always felt strongly about this. They don’t want to tell the public who they are lending to.” The central bank has never revealed identities of borrowers since the discount window began lending in 1914. The Dodd-Frank law exempted the facility last year when it required the Fed to release details of emergency programs that extended $3.3 trillion to financial institutions to stem the credit crisis. While Congress mandated disclosure of discount-window loans made after July 21, 2010 with a two-year delay, the records released today represent the only public source of details on discount- window lending during the crisis. Protecting Its Reputation “It is in the interest of a central bank to put a premium on protecting its reputation, and, in the modern world, that means it should do everything to be as transparent as possible,” said Marvin Goodfriend, an economist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh who has been researching central bank disclosure since the 1980s. “I see no reason why a central bank should not be willing to release with a lag most of what it is doing,” said Goodfriend, who is a former policy adviser at the Richmond Fed. Bloomberg News reporters received two CD-ROMs, each containing an identical set of 894 PDF files, from Fed attorney Yvonne Mizusawa at about 9:45 a.m. in the lobby of the Martin Building in Washington. Bloomberg News has posted the raw documents here. Accessing them will take several minutes. The documents show the central bank providing credit to borrowers large and small. A page described as “Primary Credit Originations, February 5, 2008” lists the New York branch of Deutsche Bank AG with a loan of $455 million from the New York Fed. On the same day, Macon Bank is listed with a $1,000 loan from the Richmond Fed. First Tool Page | 5 The discount window was the first tool Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke reached for when panic over subprime mortgage defaults caused banks to tighten lending in money markets in 2007. The Fed cut the discount rate it charged banks for direct loans to 5.75 percent on Aug. 17, 2007, and it continued to reduce the rate to 0.5 percent by the end of 2008. The rate stands at 0.75 percent today. Lending through the discount window soared to a peak of $111 billion on Oct. 29, 2008, as credit markets nearly froze in the wake of the bankruptcy on Sept. 15, 2008, of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. While the loans provided banks with backstop cash, the public has never known which banks borrowed or why. Fed officials say all the loans made through the program during the crisis have been repaid with interest. The Fed was forced to make the disclosures after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal by the Clearing House Association LLC, a group of the nation’s largest commercial banks. The justices left intact lower court orders that said the Fed must reveal documents requested by Bloomberg related to borrowers in April and May 2008, along with loan amounts. The late Bloomberg News reporter Mark Pittman asked for the records under the Freedom of Information Act, which allows citizens access to government papers. News Corp.’s Fox News Network LLC filed FOIA requests for similar information on loans made from August 2007 to March 2010. Former Fed officials, lawyers representing the central bank, and even some Fed watchers have expressed concern that revealing the names of discount-window borrowers could keep banks away from the facility in the future. “I am concerned that in the next crisis it will be more difficult for the Federal Reserve to play the traditional role of lender of last resort,” said Donald Kohn, former Fed vice chairman and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington. “Having these names made public, or the threat of having them made public, could well impair the efficacy of a key central bank function in a crisis -- to provide liquidity to avoid fire sales of assets -- because banks will be reluctant to borrow.” “I think it will make it harder for people to use the discount window in the future,” Jamie Dimon, chairman and chief executive of New York-based JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM), the second- biggest U.S. bank by assets, told reporters yesterday after a speech in Washington. “We never intend to use the discount window.” With little more than a phone call to one of 12 Federal Reserve banks, a bank anywhere in the country can ask for cash from the discount window. Banks typically have already given the Fed a list of unencumbered collateral that they use to pledge against the loans. The Fed gives the banks less than 100 cents on each dollar of collateral to protect itself from credit risk. Discount-window lending was not the largest source of the Fed’s backstop aid during the crisis. Bernanke also devised programs to loan to U.S. government bond dealers, and to support the shortterm debt financing of U.S. corporations. Page | 6