Friedman and Freeman

advertisement

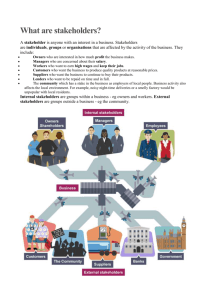

Philosophy 223 Corporate Social Responsibility: Some Background A common assumption: corporations don’t have any responsibilities. Officers of corporations do, but they are narrowly defined according to perceived interests of the owners. What becomes clear ultimately is that the view does not deny that the agents of corporations have moral obligations, just that they are very specific (primarily fiduciary). Corporations Don’t Have Responsibilities? Corporation’s are legal fictions. Don’t have the capacities necessary for responsibilities. Knowledge and will. What about the fact that corporations are frequently held criminally and civilly liable? Also, corporations are increasingly granted the rights of individual citizens (First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti). If There is Responsibility it Must be That of the Officers Only people with the appropriate capacities. But to whom are they responsible? The owners. What is the nature of that responsibility? To satisfy the will of the owners. Utilitarian Defense of Classical Model The market guarantees maximization of good (usually characterized as ‘satisfaction’). Managers have a responsibility to conform closely with market expectations (maximize satisfaction). Evidence is expressed preferences of consumers and owners. Criticisms of the Utilitarian Defense Part I There are a range of instances in which the pursuit of profits does not maximize satisfaction. Market Failures Externalities (Pollution, resource depletion). Public Goods (Air, water, fisheries)-no pricing mechanism. Prisoner’s Dilemma (cooperation more optimal than competition). Complexity of markets and the contexts in which they function make it unlikely that a single-minded focus on profit will guarantee good outcomes. Criticisms of the Utilitarian Defense Part II Of course, there may be mechanisms that could be developed to meet the sort of objections just noted. Property values an economic measure of air quality preferences. However, there are more difficult conceptual problems. First-Generation Problem: markets are reactive, not proactive. Satisfaction does not equal happiness. It’s not always good to get what you want. Private Property Defense of Classical Model Corporations are the property of their owners. Officers of corporations are responsible to the desires of the owners. The primary desire of the owners of the corporation is profit maximization. Criticisms of the Private Property Defense Right to property is not absolute. Constrained by: rights of others; zoning; eminent domain. Corporate Property Rights are different from personal property. Stockholder of a corporation have limited liability for actions of their corporations. They have no direct rights of access/control. Stakeholder Theory The current focus of much of the thinking about corporate social responsibility is Stakeholder Theory. Adherents of the theory argue that all stakeholders in a corporation have a fundamental right to respect, and thus that corporate officers have a responsibility to treat them as ends rather than as means to ends. Who is a Stakeholder? Narrow Definition Any individual or group vital to the survival and success of the corporation. Wide Definition Any individual or group whose interests can effect or are affected by the corporation. Examples? Defense of Stakeholder Theory Most defenses of Stakeholder Theory begin with the recognition that Stakeholders are conceptually related to stockholders. Justification then focuses on the reach and number of relevant normative concerns. Differences between stockholders and employees? Criticisms of Stakeholder Theory A common criticism of Stakeholder theory emerges from the classical model. Stakeholder theory inadequately addresses stockholder rights and property rights. Another criticism focuses on practical issues. Who are the stakeholders? How do they count? How should managers take them into account in their decisions? "Social Responsibility of Business" Milton Friedman was a Nobel Prize winning economist. He won for his work in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy. He was more famous, though, for his social policy work, of which the piece we read is perhaps the most infamous example. CSR? Friedman pulls no punches in this essay. His opening salvo insists that all talk of CSR is incomprehensible and declares that the business people who suggest that business has obligations beyond profit are advocating "socialism.“ A less impassioned gaze reveals that Friedman is offering a version of a private property critique of CSR. Where is the Responsibility? According to Friedman, if we are to make sense of the discussion of claims concerning the responsibility of business, we need to determine the nature of the responsibility. Friedman first asserts that the corporation itself is a legal fiction, and if there is responsibility it must be that of the executive officers. To whom are they responsible? Why the owners, of course. What is the nature of that responsibility? To satisfy the will of the owners. What do owners want? One may ask: "Why does this preclude an analysis of business that includes social responsibility?" Friedman pins his answer to a conception of such responsibility as necessarily antagonistic to the will of the owners (52). On the basis of this antagonism, Friedman equates a decision motivated by social responsibility with taxation. This in turn explains why Friedman thinks that CSR is equivalent to socialism (53). A very thin sort of responsibility. What becomes clear ultimately is that Friedman is not denying that business has some moral obligations, just that it has particular the ones typically articulated under the banner of CSR. He does however insist (without arguing for it) that corporate officers have a responsibility to play fair and play by the rules (existing laws and regulations). “Managing For Stakeholders” Freeman sets out to question the conventional wisdom that the primary or only responsibility held by corporate managers is to the stockholders. His aim is not to deny this particular responsibility, only to widen it to include all "stakeholders" in corporate practices. Freeman insists that all stakeholders are due a fundamental respect by corporate officers, that is, they have a right to be treated as an end in themselves, and not merely as a means to some specific corporate end. The Changing World He supports this claim by referring to changing legal standards, which have increasingly recognized the claims and interests of customers, labor, and communities against those of corporations. He also argues that recognizing stakeholder rights also makes economic sense, especially in light of problems like the "tragedy of the commons" which have increased government oversight of corporations, lessening their ability to make their own economic decisions. Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory Freeman then goes on to articulate the specifics of the stakeholder theory, focusing on the narrow definition of the stakeholder (those groups vital to the survival of the corporation), though he holds out the possibility of a theory that would encompass a broader notion of stakeholder (any group/individual who can affect or be affected by a corporation). Essentially, the stakeholder theory he offers is just an expansion of the traditional shareholder theory. Of course, the range of individuals involved in the theory is much broader (see diagram on p. 61). Where the stakeholder theory significantly diverges from shareholder theory is in the reach and number of relevant normative concerns. Two Key Assumptions The Integration Thesis: Most business decisions have some ethical content, or implicit ethical view. Most have ethical decisions, business content, or an implicit view about business. The Responsibility Principle: Most people, most of the time, want to, actually do, and should accept responsibility for the defects of their actions on others. Practical Implications Stakeholder interests should be regarded as joint. Stakeholder interests may be prioritized by different companies in different ways. Businesses must have a clearly defined purpose. Theoretical Foundations The argument from consequences: Results in economic, social, and environmental benefits. The argument from rights: Helps to ensure that property rights and human rights are protected. The argument from character: Helps ensure that virtues, such as efficiency, fairness, respect, and integrity are enacted by managers. The Pragmatist’s argument: Because we want humane social institutions, businesses should be regarded as a social practice governed by the norms common to all social practices.