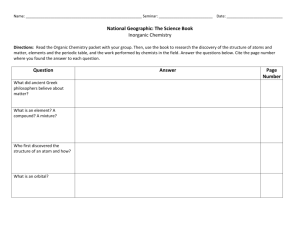

Basic Concepts of Chemical Bonding

advertisement

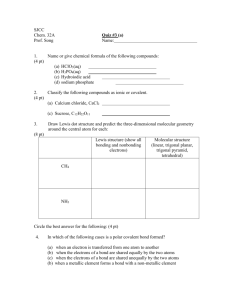

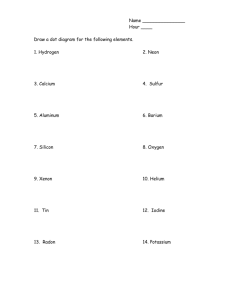

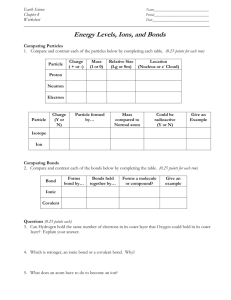

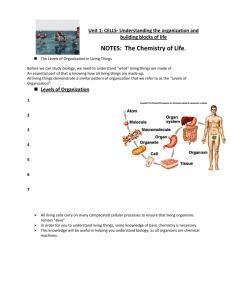

Chapter 9 Ionic and Covalent Bonding 8–1 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-1 Overview • Ionic Bonds – Describing Ionic Bonds – Electron Configuration of Ions – Ionic Radii • Covalent Bonds – – – – – Describing Covalent Bonds Polar Covalent Bonds: Electronegativity Writing Lewis Electron-Dot Formulae Bond Length and Order Bond Energy John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–2 Chapter 9-2 IONIC BONDING • Ionic bonds are electrically neutral groups that are held together by the attraction arising from the opposite charges of a cation and an anion. • Substances that have ionic bonds in a solid form a salt having high melting point and high crystallinity. • Bonding thought of as the result of the combination of neutral atoms with transfer of one or more electrons from one atom to the other. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-3 8–3 LEWIS SYMBOLS AND THE OCTET RULE • • • It was observed that the electron configuration of Na many substances after ion formation was that of Mg an inert gas octet rule. O Octet rule: Main-group elements gain, lose, or share in chemical bonding so that they attain a valence octet (eight electrons in an atoms valence shell). E.g. The electron configuration of each reactant in the formation of KCl gives: Na+ Mg2+ O 2- – K+ is that of [Ar] – Cl is also that of [Ar]. • The other electrons in the atom are not as important in determining the reactivity of that substance. • The octet rule is particularly important in compounds involving nonmetals. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–4 Chapter 9-4 Energy in Ionic Bonding • When potassium and chlorine atoms approach each other we have: K(g) K+(g) + e Ei = +418 kJ Cl(g)+ e Cl(g) Eea = 349 kJ K(g)+Cl(g) K+(g) + Cl(g) E = + 69 kJ • Positive E = energy absorbed energetically not allowed. • Driving force must be the formation of the crystalline solid. K+(g) + Cl(g) KCl(s) 8–5 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-5 Formation of Crystalline Lattice • Energy of crystallization estimated from Coulomb’s Law by zz E k 1 2 d – assuming ions are spheres. – Use ionic radii to determine charge separation. Coulomb’s Law rK+ = 133x1012 m; rCl = 181x1012 m d = 133x1012 m + 181x1012 m = 314x1012 m z1 = z2 = 1.602x1012 C(oulombs); actually one is the negative of the other. k = 8.99x109 Jm/C2 E 9 2 8.99x10 J m / C 1.602x10 314x1012 m 19 C 6.02x1023mol1 2 442 .3x103J / mol 442 .3kJ / mol 8–6 • This is related to the negative of the lattice energy, as discussed later. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-6 BORN-HABER CYCLE AND LATTICE ENERGIES • Overall energetics for the formation of crystalline solids can be determined from a Born-Haber cycle that accounts for all of the steps towards the formation of solid salts from the elements. For the formation of KCl from its elements we have: K (s) K(g) 1/ 2 Cl2(g) Cl(g) 1. Sub of t he metal 2. Dissociation of ch lorine K(g) K e 3. Ionizati on of pota ssium 4. Formatio n of chlor ide ions ( Eea) 5. Formatio n of solid KCl Sum react ions and e nergies • • • Cl e Cl K (g) Cl(g) KCl(s) K(s) 1/ 2Cl2(g) KCl(s) 89.2 kJ 122 kJ 418 kJ 348.6 kJ 715 kJ 434.4 kJ Net energy change of 434 kJ/mol indicates energetically favored. Energy for the fifth step is the negative of the lattice energy: energy required to break ionic bonds and sublime (always positive). E.g. Determine the lattice energy of BaCl2 if the heat of sublimation of Ba is 150.9 kJ/mol and the 1st and 2nd ionization energies are 502 and 966 8–7 kJ/mol, respectively. The heat for the synthesis of BaCl2(s) from its elements is 806.06 kJ/mol. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-7 Energy Level Diagram of Born Haber Cycle 8–8 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-8 LATTICE ENERGIES AND PERIODICITY zz E k 1 2 d • Lattice energy can also be determined from Coulomb’s law: Coulomb’s Law – Directly proportional to charge on each ion. – Inversely proportional to size of compound (sum of ionic radii). • Table (right) presents the lattice energies for alkali and alkaline earth ionic compounds. The lattice energies – decrease for compounds of a particular cation with atomic number of the anion. – decrease for compounds of a particular anion with atomic number of the cation. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Lat. E, kJ/mol Lat. E, kJ/mol LiF 1030 MgCl2 2326 LiCl 834 SrCl2 2127 LiI 730 MgO 3795 NaF 910 CaO 3414 NaCl 788 SrO 3217 NaBr 732 ScN 7547 NaI 682 KF 808 KCl 701 KBr 671 CsCl 657 CsI 600 8–9 Chapter 9-9 Ionic Radii • Ionic radius – a measure of the size of a spherical region around the nucleus of an atom where electrons are most likely to reside. – Cation loses electrons from its valence shell. Electrons from other valence shells are closer to the nucleus. – Cation also has more protons than electrons which adds to the pull on the remaining electrons and decreases the radius. – Anion has more electrons than protons; the pull of the nucleus is less per valence electron. Also, the electron – electron repulsion is greater. These lead to larger radius for an anion. 8–10 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-10 Ionic Radii - Trends – Ionic radii increase down any column because of the addition of electron shells. – In general, across any period the cations decrease in radius. When you reach the anions, there is an abrupt increase in 8–11 radius, and then the radius again decreases. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-11 Ionic Radii - Isoelectronic Ions • Isoelectronic substances have the same number of electrons and electron configuration. 2 2Ca K Ar Cl S 20 19 18 17 16 All have 18 electrons • Largest radius = ion with smallest number of protons. • Smallest radius = ion (atom) with largest number of protons. 8–12 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-12 The Covalent Bond • Repulsive forces of the electrons offset by the attractive forces between the electrons and the two nuclei. • Most stable bond energy and bond distance characterizes bonds between two atoms. • Strengths of Covalent Bonds: • Bonds form because their formation produces lower energy state than when atoms are separated. • Breaking bonds increases the overall energy of the system. Energy for breaking bonds has a positive sign (negative means that energy is given off). H - H (g) 2H(g) H = 436 kJ. • Ionic vs. Covalent Bonds – Ionic compounds have high melting and boiling points and tend to be crystalline; – Covalently bound compounds tend to have lower melting points since the attractive forces between the molecules are relatively weak. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–13 Chapter 9-13 Lewis Structures • Lewis structure valence electrons represented by dots and are placed where they would be in any bonding that might exist. • Lewis structures of second row elements: – H2 – CH4 – H 2O BH3 NH3 HF • Each has 8 electrons around the central atom; thus we can predict the number of bonds that will form from the position in the periodic table. .. .. E.g. The structure of chlorine is :Cl .. :Cl .. : – Bonding electrons = shared electrons. – Non-bonding or lone pair = unshared electrons John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–14 Chapter 9-14 Lewis Structures(cont’d) • • • Octet can be filled by donation of electrons from each atom or one atom can supply both electrons. E.g. H+ + NH3 NH . 4 "co-ordinate covalent bond". E.g.2 BF3 F BF4 Multiple bonds may form as a result when the two atoms forming the bond do not have enough electrons. – O=O – NN Multiple bonds are shorter and stronger than single bonds because of the extra electrons holding the two atoms together. 8–15 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-15 Polar Bonds: Electronegativity • Electronegativity is a measure of the atom’s ability to gain or lose electrons. It is directly related to its ionization tendency and its ability to form the inert gas configuration. Obtained by: Ei Eea 2 where Ei = ionization energy and Eea = the electron affiinity. E.g. Li has a very low ionization energy and electron affinity, while Cl has a both a high ionization energy and high electron affinity. Electronegativity will be high for Cl and low for Li. – Fluorine has the highest electronegativity of 4.0. • Electronegativities (see Fig. 9.15) – increase from bottom to top of periodic table and – increase to a maximum towards the top right. • • • • • Combination of elements with intermediate electronegativities forms bonds that are intermediate between covalent and ionic. can provide an insight as to the type of bond that would be expected. Ionic bonds formed when 2 covalent bonds forms when 1. Polar covalent forms when 1 2, the bonding is "intermediate" between the two. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–16 Chapter 9-16 Polar Bonds: Electronegativity2 E.g.1 Determine the polarity of the N – H in NH3. E.g. 2 Predict the type of bond formed in CCl4. • The magnitude of indicates if electrons are polarized around one element in preference to the other. • Polar bond polar. With intermediate , a small charge on the atom due to that bond develops. + and designates which is the positive and negative side respectively. E.g.3 Determine the relative polarities of HF, HCl, HBr and HI. 8–17 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-17 Lewis Structures of Polyatomic Molecules • Procedure for more complicated molecules: – Determine the total number of valence electrons from each atom. – Distributed atoms around the central atom (least electronegative. Hydrogen atoms are usually attached to any oxygen. – Satisfy the octet of the atoms bonded to the central atom. – Satisfy the octet of the central atom by distributing the remaining electrons as electron pairs around it. (multiple bonds may be necessary) E.g. Determine the Lewis structure of H2SO4. E.g. Draw the Lewis dot structures of NCl3, CSe2, and CO. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–18 Chapter 9-18 FORMAL CHARGES • Formal Charge (of an atom in a Lewis formula) the hypothetical charge obtained by assuming that bonding electrons are equally shared between the two atoms involved in the bond. Lone pair electrons belong only to the atom to which they are bound. E.g. determine the formal charge on all elements: PCl3, PCl5, and HNO3. • formal charge (FC) allows the prediction of the more likely resonance structure. • To determine the more likely resonance structure: – FC should be as close to zero as possible. – Negative charge should reside on the most electronegative and positive charge on the least electronegative element. E.g. draw the resonance structures of H2SO4; determine the formal charge on each element and decide which is the most likely structure. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–19 Chapter 9-19 Lewis Structures and Resonance • Quantum theory indicates that any position possible for an electron. • Equivalent electron positions often possible: • E.g. SO2: O=S-O and :O-S=O. – Each structure equally likely. – the true form of the molecule is a hybrid of these and is called resonance and the hybrid form is called a resonance hybrid. 8–20 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-20 Exceptions to the Octet Rule • Although many molecules obey the octet rule, there are exceptions where the central atom has more than eight electrons. – Generally, if a nonmetal is in the third period or greater it can accommodate as many as twelve electrons, if it is the central atom. – These elements have unfilled “d” subshells that can be used for bonding. E.g determine the Lewis dot structure of XeF4, ICl3, and SF4 8–21 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-21 Bond Dissociation Enthalpies • Bond dissociation energy, D – the energy required to break one mole of a type of bond in an isolated molecule in the gas phase. • Useful for estimation of heat of unknown reactions. • Average bond energies listed in tables (e.g. C – H bond); rest pf structure not very important • HO-H bond in H2O and CH3O-H bond are 492 and 435 kJ/mol. • Hess’s law can be used with bond dissociation energies to estimate the enthalpy change of a reaction. The breaking in a C – H bond would be C – H(g) C(g) + H(g) H = D = 410 kJ. – Sign always positive since energy must be supplied to break 8–22 bond. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-22 Using Bond Dissociation Enthalpies • E.g. Estimate the heat of formation of H2O(g) from bond dissociation energies. Thus determine: • H2(g) + ½ O2(g) H2O(g) Hof = ? • From the book (Table 9.5): H – H (g) 2H(g) ½ O=O O(g) 2H(g) + O(g) H – O – H (g) H2(g) + ½ O2(g) H2O(g) H = D1 = 436 kJ H = D2 = 494/2 = 247 kJ H = 2D3 = 2*459 kJ Hof = 235 kJ Actual = 241.8 kJ • Can be determined by suming all the energies for the bonds broken and subtract from if the sum of the energies for the bonds formed. E.g. 2 Estimate the energy change for the chlorination of ethylene: – CH2=CH2(g) + Cl2(g) CH2ClCH2Cl 8–23 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-23 Using Bond Dissociation Enthalpies • It may be necessary to include a phase change since many reactions or reactants are not in the gas phase. E.g. Determine the heat of formation of CCl4(l). • Solution: The reaction is: Hof = ? C(gr) + 2Cl2(g) CCl4(l) • Write the reactions and sum energies: C(gr) C(g) H1 = 715 kJ 2Cl – Cl(g) 4Cl(g) C(g) + 4Cl(g) CCl4(g) CCl4(g) CCl4(l) C(gr) + 2Cl2(g) CCl4(l) H2 = 486 H3 = 1320 H4 = 43 H = 162 kJ Actual is 139 kJ. John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 8–24 Chapter 9-24 Electronegativities 9_12 IA IIA Li 1.0 Be 1.5 Na 0.9 Mg 1.2 K 0.8 H 2.1 VIIIB IIIB IVB VB VIB VIIB Ca 1.0 Sc 1.3 Ti 1.5 V 1.6 Cr 1.6 Mn 1.5 Fe 1.8 Co 1.8 Rb 0.8 Sr 1.0 Y 1.2 Zr 1.4 Nb 1.6 Mo 1.8 Tc 1.9 Ru 2.2 Cs 0.7 Ba 0.9 La–Lu 1.1–1.2 Hf 1.3 Ta 1.5 W 1.7 Re 1.9 Os 2.2 Fr 0.7 Ra 0.9 Ac–No 1.1–1.7 IIIA IVA VA VIA VIIA B 2.0 C 2.5 N 3.0 O 3.5 F 4.0 Al 1.5 Si 1.8 P 2.1 S 2.5 Cl 3.0 IB IIB Ni 1.8 Cu 1.9 Zn 1.6 Ga 1.6 Ge 1.8 As 2.0 Se 2.4 Br 2.8 Rh 2.2 Pd 2.2 Ag 1.9 Cd 1.7 In 1.7 Sn 1.8 Sb 1.9 Te 2.1 I 2.5 Ir 2.2 Pt 2.2 Au 2.4 Hg 1.9 Tl 1.8 Pb 1.8 Bi 1.9 Po 2.0 At 2.2 Return to slide 16 8–25 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-25 8–26 Return to Slide 23 John A. Schreifels Chemistry 211 Chapter 9-26