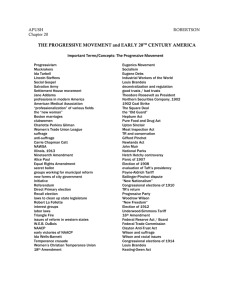

Women's Rights Movement: Liberty and Equality

advertisement

Women’s Rights Movement: Liberty and Equality Bill of Rights Institute Kansas City, Kansas October 27, 2015 Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu Colonial Women’s Rights • • • • • • During the colonial period, suffrage was largely determined by local custom. While there are few records of women voting, it is clear that some did, especially large landowners. After the revolution, individual states began to draft written constitutions and female suffrage evaporated. Women were also excluded by the gradual shift from gender-neutral, property owning requirements to near universal male suffrage. On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John, who was attending the 2nd Continental Congress, urging him to “remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors.” Adams’ admonitions to her husband had little impact on either the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, or the Constitution. Women were deliberately excluded in all of these documents and were relegated to second-class citizenship. Anti-Slavery Movement • Recognition of their inferior legal status, however, did not come overnight. • In 1840, 20 years before the Civil War, two women who were active in the American abolitionist movement traveled by boat across the Atlantic Ocean to London for the annual meeting of the International Anti-Slavery society. • After a long arduous journey, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were denied spots on the convention floor because the were women. Instead, they were relegated to the rear of the balcony. • They resolved to call a meeting to discuss women’s 2nd-class status but the antislavery movement and issues in their own lives kept them from acting for another 8 years. Declaration of Sentiments (1848) • • • • In 1848, in what is widely hailed as the first major step toward female equality in the United States, a women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. At that meeting, and also at a later meeting in Rochester, New York, a series of resolutions and a Declaration of Sentiments were drafted calling for expanded rights for women in all walks of life. The documents reflected dissatisfaction with contemporary moral codes, divorce and criminal laws, and the limited opportunities for women to obtain an education, participate in the church, and enter careers in medicine, law, and politics. While these issues continue to dominate the field of sex discrimination law today, none of the participants at Seneca Fall or subsequent meetings saw the U.S. Constitution as a potential source of rights for women. American Equal Rights Association (1866) • • • • While women continued to press for changes in state laws to ameliorate their inferior legal status, they also continued to be active in the abolitionist movement. During the Civil War most women’s rights activists concentrated on the war effort and abolition. Many who had been present at Seneca Falls or active in subsequent efforts for women’s rights joined the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), an association dedicated to abolition and woman suffrage. AERA members saw the issues of slavery and women’s rights as inextricably intertwined, believing that suffrage would be granted when the franchise was extended to newly freed slaves. The 14th Amendment (1868) • • • • • Even the AERA, however, soon abandoned the cause of female suffrage with its support of the proposed 14th Amendment. When a majority of its members agreed that “Now is the Negro’s hour,” key women’s right’s activists including Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (left) were outraged. They were particularly incensed by the test of the proposed amendment, which introduced the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time. Although Article II of the Constitution does refer to the president as “he,” the use of the word “male” to limit suffrage was infuriating to many women. Not only did Anthony and Stanton argue that women should not be left out of any attempt to secure fuller rights for freed slaves, but they were concerned that the text of the proposed amendment would necessitate the passage of an additional amendment to enfranchise women. The 15th Amendment (1870) • How right they were. Soon after the passage of the 14th Amendment, the 15th Amendment was added, enfranchising black males previously ineligible to vote. • Feverish efforts to have the word “sex” added to the amendment’s list of race, color, or previous condition of servitude as improper limits on voting were unsuccessful. • Women were once again told that the rights of AfricanAmericans must come first. National Women’s Suffrage Association (1869) • Passage of the 15th Amendment, and the AERA’s support of it, led Anthony and Stanton to found the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. • Its relatively radical demands for the reform of family and standards of dress, as well as its support of a well-known supporter of free love, Victoria Woodhull, led many to derided its more conservative demand for suffrage via a national constitutional amendment. Victoria Woodhull NWSA Publicity Efforts • • • • The NWSA’s advocacy of controversial reforms led to a severe image problem for both the association and its goals. In 1869, to led credibility to its cause as well as to short-circuit the possibility of a long battle for a universal suffrage amendment, Francis Minor, an attorney and the husband of a prominent NWSA member, put forth his belief that women, as citizens, were entitled to vote under the existing provisions of the 14th Amendment. Minor saw the NWSA’s possible resort the courts as a means to gain favorable publicity for the organization. Victoria Woodhull’s presentation to Congress in 1871, urging them to pass enabling legislation to give women the right to vote under the 14th Amendment, provided the impetus for renewed efforts. NWSA Strategy Susan B. Anthony • Minor, along with Susan B. Anthony, quickly seized on the enthusiasm that Woodhull’s suggestions created. • Minor urged that test cases be brought to determine if the courts would obviate the need for additional legislative action. • A number of legal scholars and judges had publicly agreed with Minor’s arguments, and, moreover, in rejecting Woodhull’s request for enabling legislation, the House of Representatives had noted that if a right to vote was vested by the Constitution, that right could be established in the courts without further legislation. • More importantly, the newly appointed Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase had suggested that women test the parameters of the Constitution to determine if they were already enfranchised by its provisions. Race to the Court Roger Taney • Despite Chase’s encouragement, prior references to women by the Supreme Court had generally accepted a limited role for them. • In Dred Scott (1857), for example, Chief Justice Taney noted, “Women and minors, who form a part of the political family, cannot vote.” • Ignoring this discouraging language, the NWSA initiated several test cases hoping to have at least one heard by the Supreme Court. • They had reason to be hopeful as the post-Civil War Reconstruction era had ushered in a progressive time in the South for AfricanAmericans. • But before one of their voting rights test cases could be heard by the justices, a different case involving women—one not tied to the NWSA’s litigation strategy—got there first. Bradwell v. Illinois (1873) • • • • Joseph Bradley Myra Bradwell studied law with her attorney husband and published the Chicago Legal News—a leading legal publication of the time. She applied for admission to the state bar and the Illinois Supreme Court denied the application because she was a woman. A state statute provided that any adult person with sufficient training was eligible for admission, so she sought a writ of error from the U.S. Supreme Court claiming a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment Privileges or Immunities Clause. Justice Samuel Miller delivered the 8-1 opinion holding that women could be prohibited from practicing law. Miller cited the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) as precedent and held that the Fourteenth Amendment did not cover the right to practice a profession, therefore it was up to individual states to decide such matters. Justice Joseph Bradley, however, issued a concurring opinion focusing on the fact that Bradwell was a woman. He argued that “[t]he natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life... The paramount destiny and mission of women are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator.” Bradley’s statement was seemingly at odds with his dissent in the Slaughterhouse Cases, where he had argued (with respect to men) that "the right of any citizen to follow whatever lawful employment he chooses to adopt (submitting himself to all lawful regulations) is one of his most valuable rights, and one which the legislature of a State cannot invade, whether restrained by its own constitution or not." Bradwell’s Aftermath • The only dissenter (without issuing any opinion) in Bradwell, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, died and was replaced by Morrison R. Waite (right). • The Court finally heard one of the NWSA’s test cases in 1874—two years before the disputed Hayes/Tilden election of 1876 that would undue gains made by AfricanAmericans during Reconstruction. • Would the NWSA be able to take advantage of the progressive era of Reconstruction? Minor v. Happersett (1875) • • • • • • The Missouri Constitution says: “Every male citizen of the United States shall be entitled to vote.” Virginia Minor, one of the leaders of the NWSA, attempted to register to vote in 1872 Missouri. When she was denied by the registrar of voters, she brought suit in the state courts under the U.S. Constitution’s Privileges or Immunities Clause and lost. There was no opposing counsel at the U.S. Supreme Court. Chief Justice Morrison Waite delivered the unanimous decision of the Court in favor of the Missouri, holding that the denial of the vote to women did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. After determining that Minor was indeed a citizen, the decision held that the Constitution neither granted nor forbade the right to vote to women and voting is not an inherent right of citizenship. “It cannot for a moment be doubted that if it had been intended to make all citizens of the United States voters, the framers of the Constitution would not have left it to implication. So important a change in the condition of citizenship as it actually existed, if intended, would have been expressly declared.” International Council of Women (1888). Susan B. Anthony, seated second from left, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, seated fourth from left, and members of the first International Council of Women, which met in Washington, D.C., in 1888 to discuss women’s rights. Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire (1911) Youtube clip: PBS, New York – 4 (36 min.) Power to the People @ 1:07:56 – 1:44:08 • • • • Women began attending college in higher numbers and entering the workforce out of necessity. Young women, especially immigrants, were confined to low-paying jobs in substandard conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City put the issue on the national agenda. In its wake, New Yorkers demanded and the legislature passed laws protecting workers from dangerous working conditions. National Consumer’s League • • • • • • Calls for improved working conditions for women and children began to pick up steam around the nation. The organization most responsible for change, and for the Court again addressing issues of gender, was the National Consumer’s League (NCL). Through the work of its national staff and numerous affiliates, the NCL secured maximum-hour or other restrictions on night work for women in 18 states. The NCL asked Louis Brandeis, the brother-in-law of one of the organization’s most active members and already a famous progressive lawyer, to take the case of Muller v. Oregon (1908). Brandeis agreed but under one condition—that he have sole control over the litigation—Oregon agreed and allowed the NCL (and Brandeis) to represent the group in Court. The precedent for Muller was Lochner v. New York (1905), where the Court invalidated a law regulating the work hours of bakers under a substantive view of “liberty” under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause: liberty, or freedom of contract between employers and employees, which had to be balanced against the police powers of the state. Louis Brandeis “Brandeis Brief” (1908) • Brandeis knew that in order to win the case, he would have to present information to show that the dangers to women working more than 10 hours a day made them more deserving of state protection than the bakers in Lochner, and by proving that there was something different about women that justified an exception to the freedom of contract doctrine. • NCL researchers compiled information about the possible detrimental effects of long work hours on women’s health and morals, as well as on the health and welfare of their children, including t heir unborn children. • Brandeis stressed women’s differences from men and the reasonableness of the state’s legislation (low-level scrutiny). • In fact, the brief had only 3 pages of legal argument and 110 pages of sociological data culled largely from European studies of the negative effects of long hours of work on women’s health and reproductive capabilities. • Some examples… “Brandeis Brief” (1908) • “The leading countries in Europe in which women are largely employed in factory or similar work have found it necessary to take action for the protection of their health and safety and the public welfare, and have enacted laws limiting the hours of labor for adult women…” • “Twenty states of the Union…have enacted laws limiting the hours of labor for adult women…. In no state has any such law been held unconstitutional, except in Illinois…” • Brandeis provided reports such as: • “Report of Select Committee on Shops Early Closing Bill, British House of Commons, 1895” where a doctor describes the deterioration of the health of women who work long hours. • “Report of the Maine Bureau of Industrial and Labor Statistics, 1888” where a doctor described the adverse effects of standing for 8-10 hours a day – linking it with infant mortality rates. • Should judges consider such information? Muller v. Oregon (1908) • • • In 1903 Oregon enacted a law that limited women to 10 hours of work in factories and laundries. A laundry business owner was convicted of violating the law by forcing female employees to work excessive hours. Does the Oregon law violate a woman’s freedom of contract implicit in the liberty protected by Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? Attorney—and future Supreme Court justice—Louis Brandeis argued on behalf of the state that excessive hours harmed women. He provided a lengthy legal brief that included medical studies and other material not traditionally used in legal argumentation to justify the law. This type of legal brief became known as the Brandeis brief and influenced a generation of lawyers. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice David Brewer noted Brandeis’ extensive analysis and upheld the statute. Though the opinion contained language that patronized women, Brewer said that liberty of contract was not an absolute right and must be balanced against the police power of the state to protect the health, safety, welfare, and morals of its people. • • Muller v. Oregon (1908) “That woman’s physical structure and the performance of maternal functions place her at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence is obvious. This is especially true when the burdens of motherhood are upon her. Even when they are not, by abundant testimony of the medical fraternity continuance for a long time on her feet at work, repeating this from day to day, tends to injurious effects upon the body, and, as healthy mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, the physical well-being of woman becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength and vigor of the race.” “History discloses the fact that woman has always been dependent upon man. He established his control at the outset by superior physical strength… (which) has continued to the present…. It is impossible to close one’s eyes to the fact that she still looks to her brother and depends on him…. The two sexes differ in structure of body, in the functions to be performed by each, in the amount of physical strength, in the capacity for long continued labor, particularly when done standing, the influence of vigorous health upon the future well-being of the race, the self-reliance which enables one to assert full rights, and in the capacity to maintain the struggle for subsistence. This difference justifies a difference in legislation, and upholds that which is designed to compensate for some of the burdens which rest upon her.” Muller v. Oregon (1908) • Does the Court mention the fact that women cannot vote in Oregon? • Yes, but it doesn’t matter: “We have not referred in this discussion to the denial of elective franchise in the state of Oregon, for while that may disclose a lack of political equality in all things with her brother, that is not of itself decisive. The reason runs deeper, and rests in the inherent difference between the two sexes, and in the different functions in life which they perform.” • Do they overturn Lochner? • No. They distinguish it: “For these reasons, and without questioning in any respect the decision in Lochner v. New York, we are of the opinion that it cannot be adjudged that the act in question is in conflict with the Federal Constitution, so far as it respects the work of a female in a laundry, and the judgment of the Supreme Court of Oregon is affirmed.” Muller’s Progeny • Muller had an immediate effect. State courts began to hold other forms of protective legislation for women constitutional, whether or not they involved the kind of 10-hour maximums at issue in Muller. • Thus, 8-hour maximum work laws in a variety of professions, outright bans on night work for women, and minimum-wage laws for women were routinely upheld under the Muller rationale. • Much of this Court-sanctioned governmental protection, however, worked to keep women out of high-paying evening jobs or positions that they desperately needed to support their families. Suffragists Parade Down Fifth Avenue (1917). Advocates march in October 1917, displaying placards containing the signatures of over one million New York women demanding to vote. Stettler v. O’Hara (1917): Brandeis Joins the Court • • • • • • The NCL’s efforts to protect women from unscrupulous employers were victorious in the Supreme Court in several additional cases, but then ran into trouble in the early 1920s. In Stettler v. O’Hara (1917) a lower court decision upholding Oregon’s minimum-wage law for women was appealed to the Supreme Court. Conservatives argued that freedom of contract and Lochner were controlling. Brandeis was again hired and he filed another brief explaining how a living wage was essential to the health, welfare, and morals of women. But before the Supreme Court could decide the case, Brandeis was appointed to it! The case was reargued and the justices split 4-4 with Brandeis not participating, thus sustaining the lower court decision. Louis Brandeis Bunting v. Oregon (1917) • The next NCL sponsored case, Bunting v. Oregon (1917) attracted significant attention. • Brandeis’ hand-picked successor as counsel for the NCL, Felix Frankfurter, used the same kinds of arguments Brandeis had used in Muller and Stettler. • In a 5-3 decision, again with Brandeis not participating, the Court extended Muller to uphold an Oregon maximum hour statute for all factory and mill workers. th 19 Amendment (1920) • Although the NCL was victorious in Muller and Bunting, it did not anticipate the effect that the controversy within the suffrage movement would have on pending litigation. • In 1920, the movement was successful in overturning Minor v. Happersett (1875) by passing the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote—50 years after the 15th Amendment guaranteed voting rights to African-American males. The National Woman’s Party and an Equal Rights Amendment • Once the 19th was ratified, attempts were made to secure other rights for women. • Women in the more radical branch of the suffrage movement, represented by the National Woman’s Party (NWP), proposed the addition of an equal rights amendment to the Constitution. • Progressives and those in the NCL were horrified because they believed that an equal rights amendment would immediately overturn Muller and Bunting and invalidate all the protective legislation they had lobbied so hard to enact. Alice Paul: Co-founder NWP Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) • • • • • • • • When Adkins came to the Court, the NCL was ready. Adkins involved the constitutionality of a Washington, DC minimum wage law for women. The NWP filed an amicus brief urging the Court to rule that, in light of the 19th Amendment, women should be viewed on a truly equal footing with men. The division among women between equal rights and protective legislation was now exposed to public view and was a debate resurrected again and again both in the Court and in public discourse—and continues to this day. Many thought the Court had essentially overruled Lochner in the Bunting decision, which upheld limits on factory and mill workers. Yet in Adkins, the Court seemed to resurrect Lochner, ruling 5-4 that minimum wage laws for women were an unconstitutional violation of liberty of contract. But the Court did not overturn Muller and Bunting, choosing instead to distinguish them. It was obvious to many that the Court had been influenced by the passage of the 19th Amendment and the pro-equality arguments of the NWP. Conclusion: New Deal Equality? • • • • • The Great Depression and the election of Franklin Roosevelt and New Deal Democrats to Congress in 1932 ultimately transformed American and the Court. In West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937) the Court abandoned the liberty of contract doctrine, explicitly overruled Adkins, and upheld a minimum-wage law for women. By United States v. Darby Lumber (1941) the Court unequivocally upheld Congress’s authority to pass the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulated maximum hours and minimum wages for ALL workers. It appeared that the legal distinction between men and women had disappeared and no new women’s rights cases came to the Court until 1948. But it was not until the women’s rights movement of the 1970s that saw the next wave of policy changes to promote women’s liberty and equality.