Plato, Phaedo

advertisement

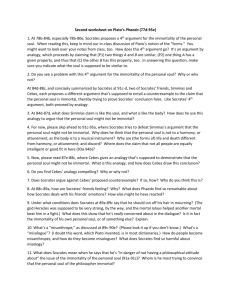

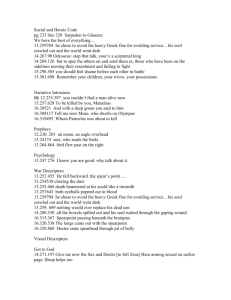

Plato, Phaedo SOCRATES LAST DAY IN PRISON WHERE HE TALKS WITH FRIENDS ABOUT THE IMMORTALITY OF THE SOUL Outline Prison Scene & opening conversation – 57-61d The Philosopher’s attitude toward death – 61d-69e Immortality - argument from reciprocal processes 69e-72e - argument from recollection 72e-77c - relation of body to soul 77c-84c Objections to Immortality - soul may not be an attunement 84c-86d - durability is not immortality 86d-88d Interlude in which faith in conversation is affirmed 88d-91c Answers to Objections Soul is not an attunement 91c-95a Theory of Forms 95a-107a Myth of Paradise and the destination of souls 107a-114d Evening in the prison 114d Prison scene and opening conversation Distancing devices Delay of Socrates execution – The sacred trip to Delos Socrates’ calm and contentment Pleasure and pain Dislike of exaggerated emotion – Apollodorus and Xanthippe (his wife) Poetry writing and telling stories Cebes and Simmias both Pythagorean philosphers The philosopher’s attitude toward death and the illegitimacy of suicide The Philosopher welcomes death, but does not instigate his own (61). We are the property of the gods: they would be angered and would likely punish you for destroying their property (62c). We should welcome death: (i) we are in the god’s protection (62d); we will visit with the gods and good men after death (63b-c); philosophy is a practicing for death – escape from the body “True philosophers are nearly dead … and deserve to be…” (64c). Body vs. soul Death is the separation of body and soul (64). The philosopher is interested in the pleasures of the soul, not the body (65). In fact, the philosopher dislikes the body since it misleads us and is a hindrance to knowledge acquisition (65b-d). The Just Itself, the Beautiful Itself, the Good Itself (i.e., their Forms) cannot be sensed by the body and can be accessed only through the mind alone (65e-66a) Death as the separation of soul from body is, then, when we are most likely to learn (67a-c). Nature of Forms (65dff) Absolute (not relative) Immaterial Really Real – the essence of a thing Rationalism vs. empiricism Reciprocal Processes (70a-72e) or the Argument from Opposites Cebes’ worry: the soul disperses upon the death of the body. Socrates’ ‘story’: “… souls arriving there come from here, and then again they arrive here and are born again from the dead” (70c). 1. All things come to be from their opposite states: for example, something that comes to be “larger” must necessarily have been “smaller” before (70e71a). 2. Between every pair of opposite states there are two opposite processes: for example, between the pair “smaller” and “larger” there are the processes “increase” and “decrease” (71b). 3. If the two opposite processes did not balance each other out, everything would eventually be in the same state: for example, if increase did not balance out decrease, everything would keep becoming smaller and smaller (72b). 4. Since “being alive” and “being dead” are opposite states, and “dying” and “coming-to-life” are the two opposite processes between these states, coming-to-life must balance out dying (71c-e). 5. Therefore, everything that dies must come back to life again (72a). Reciprocal Processes: Possible Problems Impersonal vs. personal immortality. Soul separates from our body (which disperses) at death. It then returns to a different body. Is this still us? Are ‘we’ immortal? Does the principle about balance in (3), for instance, necessarily apply to living things? Couldn’t all life simply cease to exist at some point, without returning? How do we account for increases or decreases in population. The world now has ~ 7 billion people: in 400BCE, it had ~ 125 million. Reciprocal Processes: Possible Problems Contradictory qualities vs. contrary ones In a first sense, it is used for “comparatives” such as larger and smaller (and also the pairs weaker/stronger and swifter/slower at 71a), opposites which admit of various degrees and which even may be present in the same object at once (on this latter point, see 102b-c). However, Socrates also refers to “being alive” and “being dead” as opposites—but this pair is rather different from comparative states such as larger and smaller, since something can’t be deader, but only dead. Being alive and being dead are what logicians call “contraries” (as opposed to “contradictories,” such as “alive” and “not-alive,” which exclude any third possibility). With this terminology in mind, some contemporary commentators have maintained that the argument relies on covertly shifting between these different kinds of opposites. Argument from Recollection (72e-77c) Cebes references slave boy example. Socrates then adds a different sort of recollection where we look at one thing, and it causes us to think (or recollect) something different. E.g., your lover’s lyre makes you think of her (associationism). This wouldn’t happen if you didn’t recollect the two together. Socrates elaborates on this to discuss recollecting immaterial Forms. Argument from Recollection 1. Things in the world which appear to be equal in measurement are in fact deficient in the equality they possess (74b, d-e). 2. Therefore, they are not the same as true equality, that is, “the Equal itself” (74c). 3. When we see the deficiency of the examples of equality, it helps us to think of, or “recollect,” the Equal itself (74c-d). 4. In order to do this, we must have had some prior knowledge of the Equal itself (74d-e). 5. Since this knowledge does not come from sense-perception, we must have acquired it before we acquired senseperception, that is, before we were born (75b ff.). 6. Therefore, our souls must have existed before we were born. (76d-e) Argument from Recollection: Possible Problems This argument is an improvement over what was offered in the Meno because it does offer some explanation of knowledge acquisition in another life (when freed from distractions of the body) The argument is dependent, as Simmias says, on the theory of Reality provided by the Forms (76e-77a). Note that there is very little argument to support this theory. Simmias’ arg.: Socrates’ arg. is only half complete: it shows that the soul must exist before birth but not that it exists after death (which is the major concern). Socrates’ response: use this arg. jointly with reciprocal processes and his next arg. on the soul/body relation Relation of Body to Soul (or the affinity argument) Overview: an inductive argument – the properties of Forms are like the properties of the soul in many respects. Since one of the properties of the Forms is that they are everlasting, it is likely that the soul is everlasting as well. Induction vs. deduction Note that this argument is intended to establish only the probability of the soul’s continued existence after the death of the body—“what kind of thing,” Socrates asks at the outset, “is likely to be scattered [after the death of the body]?” (78b; my italics) Affinity argument 1. There are two kinds of existences: (a) the visible world that we perceive with our senses, which is human, mortal, composite, unintelligible, and always changing, and (b) the invisible world of Forms that we can access solely with our minds, which is divine, deathless, intelligible, non-composite, and always the same (78c-79a, 80b). 2. The soul is more like world (b), whereas the body is more like world (a) (79b-e). 3. Therefore, supposing it has been freed of bodily influence through philosophical training, the soul is most likely to make its way to world (b) when the body dies (80d-81a). (If, however, the soul is polluted by bodily influence, it likely will stay bound to world (a) upon death (81b-82b).) Two worlds view The World of the Senses The World of Forms Composites (ie, things with parts) Non-composites Things that never remain the same Things that always remain the from one moment to the next same same and don’t tolerate any change Any particular thing that is equal, beautiful, and so forth That which is visible The Equal, the Beautiful, and what each thing is in itself That which is grasped by the mind and invisible Reasons to become a philosopher Those tied to the body will suffer at death: roam as ghosts – become ‘bad’ animals in next reincarnation Those tied to the mind will spend the next life with the gods – have access to Forms, come to acquire knowledge Death for philosophers the release out of the prison of the body Objections: The Soul is an attunement Simmias Analogy b/w relation of soul to body and music to guitar (or lyre) Soul and music – harmony, more divine, invisible Body and guitar– material, visible But the music is dependent on the physical guitar: Once it ends, so does the music Similarly for the soul. It ends when the physical body ends Pythagorean theory: the soul as a force which keeps the body together but has no independent existence Objections: durability is not = to immortality Cebes Unlike Simmias, Cebes believes the soul survives death, but… Analogy to a coat and its owner: Just as a person may survive many coats in their lifetime, a soul may survive the death of many bodies. But this speaks to the greater durability of people and souls over coats and bodies, not their immortality. Perhaps people/souls can wear out. Hence, to not fear death, we need an argument that the soul is not damaged by many births and deaths and is immortal, not just durable. Heraclitean theory where change is omnipresent: The soul remakes the body but, like the person/tailor, dies/changes at come point.. Interlude: The restoration of faith in conversation Misology and misanthropy analogy. We shouldn’t hate all people because one whom we have put our faith in has disappointed us. More experience of people and better judgment on our part will allow us to separate the good from the bad and not think all are bad. Similarly don’t loose faith in arguments because one we believed in has led us astray. We must be more vigilant to discern good from bad arguments, not drop argumentation altogether. Responses to Simmias (91e – 95a) Method of Hypothesis (again). They are all willing to accept the theory of Recollection (and with it the Theory of Forms). Given this, Socrates makes three arguments against Simmias’ theory First argument If the soul exists before (and hence independently of) the body, then the soul can’t be dependent on the body, and can’t be the harmony of the body. Responses to Simmias (91e – 95a) Second argument (1) No soul is any more a soul than another soul. I.e., there are no degrees of ‘soulness’ (2) However, souls do differ in their virtue; some are good, others are not. (3) Simmias’ theory is that a soul is an attunement or harmony. (4) They agree on this account that a good soul is like an instrument in tune (or harmony). A bad soul is like a soul out of tune (or in disharmony). (5) This creates an inconsistency since (4) with (3) implies some souls are more souls than others while (1) maintains that this can’t be. Hence, the soul is not a harmony Responses to Simmias (91e – 95a) Third argument (1) if the soul is never out of tune with its component parts (as shown at 93a), then it seems like it could never oppose these parts. (2) But in fact it does the opposite: i.e., the soul is capable of opposing and governing our component parts – such as emotions and appetites. E.g., “ruling over all the elements of which one says it is composed, opposing nearly all of them throughout life, directing all their ways, inflicting harsh and painful punishment on them, . . . holding converse with desires and passions and fears, as if it were one thing talking to a different one . . .” (94c9-d5). A passage in Homer, wherein Odysseus beats his breast and orders his heart to endure, strengthens this picture of the opposition between soul and bodily emotions. Therefore, the soul isn’t an attunement or a harmony. Review of Socrates’ response to Simmias In the three arguments against Simmias’ thesis that the soul is an attunement or harmony, Socrates makes the following 4 points: (1) the soul can exist before the body is made, (2) there are no degrees of soul like there are degrees of attunement, (3) if the attunement argument were correct, it would imply that no souls were better or worse than any other souls, and (4) the soul is master of the body. Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) This requires “a thorough investigation of the cause of generation and destruction” (96a) Socrates’ Intellectual History (96a-102a) Intrigue as a youth with natural sciences: material and efficient causes. (Growth as the addition of some material thing – we get taller ‘by a head’. Led to confusion. How does 1+1=2? Simply brought together? How is it that when one is divided in two, the reason for its becoming two is the division. In the first case, one becomes two through addition, in the second case, one becomes two through division: how can both addition and division be the reasons for one becoming two? Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) Anaxagoras – Mind – but just another materialist No final cause – the purpose for Socrates sitting here is that he believes it is improper to run away, etc. (teleology). Necessary vs. sufficient conditions. Material and efficient causes may be necessary but not sufficient for full explanations. Socrates’ own method: Hypothesis. Start with what we know best and see what follows from that assumption. The Theory of Forms is what we know best. Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) Participating in Forms best explains causation/change. E.g., A person becomes taller by participating in the Form of Tallness and 1 + 1 = 2 by 1 participating in the Form of Duality (or Twoness). Similarly dividing 1 into 2 is done by participating in the Form of Duality as well. How? Perhaps this explains being, i.e., how things are, but it doesn’t seem to explain becoming. How (or why?) does something stop participating in Shortness (or Singularity) to participate in Tallness (or Duality)? Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) Plato explains the causal relationship between Forms and objects in the world by saying that things participate in the Forms. Three explanations for this: (1) Forms as paradigms: Forms are the perfect instance of whatever they represent. For instance, the Form of Justice is the paradigm of justice, the one, most perfect instance of justice in this world. All other things that are just are just only insofar as they emulate, or are similar to, this Form of Justice. Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) (2) Forms as universals: Forms are that which all instances of the Form have in common. The Form of Justice is that quality which all just people have in common. According to this interpretation, one participates in the Form of Justice by sharing in that quality of justice. Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) (3) Forms as stuffs: Forms are distributed throughout the world. The Form of Justice, under this interpretation, is not some separate thing, but is rather the sum total of all the instances of justice that we might find in the world. There is a little bit of justice in me, there is a little bit of justice in you, and if we were to gather all these little bits of justice together, we would have the Form of Justice. Thus, each one of us participates in the Form of Justice by having a bit of the Form in us, like sharing a small piece of a very big pie. Response to Cebes (95a – 107b) 1. Nothing can become its opposite while still being itself: it either flees away or is destroyed at the approach of its opposite. (For example, “tallness” cannot become “shortness”) (102d-103a) 2. This is true not only of opposites, but in a similar way of things that contain opposites. (For example, “fire” and “snow” are not themselves opposites, but “fire” always brings “hot” with it, and “snow” always brings “cold” with it. So “fire” will not become “cold” without ceasing to be “fire,” nor will “snow” become “hot” without ceasing to be “snow.”) (103c-105b) 3. The “soul” always brings “life” with it. (105c-d) 4. Therefore “soul” will never admit the opposite of “life,” that is, “death,” without ceasing to be “soul.” (105d-e) 5. But what does not admit death is also indestructible. (105e-106d) 6. Therefore, the soul is indestructible. (106e-107a) Objections considered and answered When someone objects that premise (1) contradicts his earlier statement (at 70d-71a) about opposites arising from one another, Socrates responds that then he was speaking of things with opposite properties, whereas here is talking about the opposites themselves. Careful readers will distinguish three different ontological items at issue in this passage: (a) the thing (for example, Simmias) that participates in a Form (for example, that of Tallness), but can come to participate in the opposite Form (of Shortness) without thereby changing that which it is (namely, Simmias) (Tallness is not an essential or necessary property of Simmias.) (b) the Form (for example, of Tallness), which cannot admit its opposite (Shortness) (c) the Form-in-the-thing (for example, the tallness in Simmias), which cannot admit its opposite (shortness) without fleeing away of being destroyed Objections considered and answered Premise (2) introduces another item: (d) a kind of entity (for example, fire) that, even though it does not share the same name as a Form, always participates in that Form (for example, Hotness), and therefore always excludes the opposite Form (Coldness) wherever it (fire) exists. Essential or necessary properties vs. accidental or incidental properties This new kind of entity puts Socrates beyond the “safe answer” given before (at 100d) about how a thing participates in a Form. His new, “more sophisticated answer” is to say that what makes a body hot is not heat—the safe answer—but rather an entity such as fire. In like manner, what makes a body sick is not sickness but fever, and what makes a number odd is not oddness but oneness (105b-c). Premise (3) then states that the soul is this sort of entity with respect to the Form of Life. And just as fire always brings the Form of Hotness and excludes that of Coldness, the soul will always bring the Form of Life with it and exclude its opposite. Objections considered and answered However, one might wonder about premise (5). Even though fire, to return to Socrates’ example, does not admit Coldness, it still may be destroyed in the presence of something cold—indeed, this was one of the alternatives mentioned in premise (1). Similarly, might not the soul, while not admitting death, nonetheless be destroyed by its presence? Socrates tries to block this possibility by appealing to what he takes to be a widely shared assumption, namely, that what is deathless is also indestructible: “All would agree . . . that the god, and the Form of Life itself, and anything that is deathless, are never destroyed” (107d). For readers who do not agree that such items are deathless in the first place, however, this sort of appeal is unlikely to be acceptable. Myth of Paradise and destination of souls (107c-115a) (1) the judgment of the dead souls and their subsequent journey to the underworld (107d-108c) (2) the shape of the earth and its regions (108c-113c) (3) the punishment of the wicked and the reward of the pious philosophers (113d-114c) Myth of Paradise and destination of souls (107c-115a) When people die, those who lived a neutral life set out for Acheron, and spend a certain period of time in the underworld, where they are punished for their sins and rewarded for their good deeds, and then are returned to the earth once more. Those who have been irredeemably wicked are hurled into Tartarus, never to return. Those who have been good, however, ascend to the true surface of the earth, and those who have completely purified themselves through philosophy will live without a body altogether, and will reach places indescribably more beautiful even than the true surface of the earth. Socrates’ Death (115a-118a) No need to postpone things (by drinking poison later and ‘partying’ until the end). Gentle Death Prayer at the end. “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius; make this offering to him and do not forget.” Death as a cure for the sickness of life?