Shock & IV Fluids

advertisement

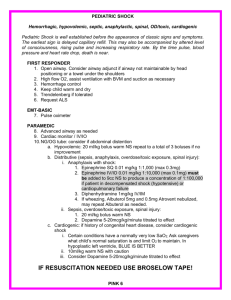

SHOCK & IV FLUIDS Dr. Ahmed Khan Sangrasi Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, LUMHS Jamshoro Shock Shock is a life threatening medical condition that occurs due to inadequate substrate for aerobic cellular respiration. Shock is a common end point of many medical conditions and one of the most common causes of death for critically ill people Objectives Definition Approach to the hypotensive patient Types Specific treatments Definition of Shock • Inadequate oxygen delivery to meet metabolic demands • Results in global tissue hypoperfusion and metabolic acidosis • Shock can occur with a normal blood pressure and hypotension can occur without shock Understanding Shock • Inadequate systemic oxygen delivery activates autonomic responses to maintain systemic oxygen delivery • Sympathetic nervous system • NE, epinephrine, dopamine, and cortisol release • Causes vasoconstriction, increase in HR, and increase of cardiac contractility (cardiac output) • Renin-angiotensin axis • Water and sodium conservation and vasoconstriction • Increase in blood volume and blood pressure Understanding Shock • Cellular responses to decreased systemic oxygen delivery • ATP depletion → ion pump dysfunction • Cellular edema • Hydrolysis of cellular membranes and cellular death • Goal is to maintain cerebral and cardiac perfusion • Vasoconstriction of splanchnic, musculoskeletal, and renal blood flow • Leads to systemic metabolic lactic acidosis that overcomes the body’s compensatory mechanisms Global Tissue Hypoxia • Endothelial inflammation and disruption • Inability of O2 delivery to meet demand • Result: • Lactic acidosis • Cardiovascular insufficiency • Increased metabolic demands Multiorgan Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) • Progression of physiologic effects as shock ensues • • • • Cardiac depression Respiratory distress Renal failure DIC • Result is end organ failure 1. ANTICIPATION STAGE 2. PRE-SHOCK STAGE 3. COMENSATED SHOCK STAGE 4. DECOMPENSATED SHOCK STAGE (REVERSABLE) 5. DECOMPENSATED SHOCK STAGE (IRREVERSABLE) Approach to the Patient in Shock • ABCs • • • • • • • Cardiorespiratory monitor Pulse oximetry Supplemental oxygen IV access ABG, labs Foley catheter Vital signs including rectal temperature Diagnosis • Physical exam (VS, mental status, skin color, temperature, pulses, etc) • Infectious source • Labs: • • • • • • CBC Chemistries Lactate Coagulation studies Cultures ABG Further Evaluation • • • • • • • CT of head/sinuses Lumbar puncture Wound cultures Acute abdominal series Abdominal/pelvic CT or US Cortisol level Fibrinogen, FDPs, D-dimer Approach to the Patient in Shock • History • • • • • • • • Recent illness Fever Chest pain, SOB Abdominal pain Comorbidities Medications Toxins/Ingestions Recent hospitalization or surgery • Baseline mental status • Physical examination • Vital Signs • CNS – mental status • Skin – color, temp, rashes, sores • CV – JVD, heart sounds • Resp – lung sounds, RR, oxygen sat, ABG • GI – abd pain, rigidity, guarding, rebound • Renal – urine output Is This Patient in Shock? • Patient looks ill • Altered mental status • Skin cool and mottled or hot and flushed • Weak or absent peripheral pulses • SBP <110 • Tachycardia Yes! These are all signs and symptoms of shock Shock • Do you remember how to quickly estimate blood pressure by pulse? • If you palpate a pulse, you know SBP is at least this number 60 70 80 90 Goals of Treatment • ABCDE • • • • • Airway control work of Breathing optimize Circulation assure adequate oxygen Delivery achieve End points of resuscitation Airway • Determine need for intubation but remember: intubation can worsen hypotension • Sedatives can lower blood pressure • Positive pressure ventilation decreases preload • May need volume resuscitation prior to intubation to avoid hemodynamic collapse Control Work of Breathing • Respiratory muscles consume a significant amount of oxygen • Tachypnea can contribute to lactic acidosis • Mechanical ventilation and sedation decrease WOB and improves survival Optimizing Circulation • Isotonic crystalloids • Titrated to: • CVP 8-12 mm Hg • Urine output 0.5 ml/kg/hr (30 ml/hr) • Improving heart rate • May require 4-6 L of fluids • No outcome benefit from colloids Maintaining Oxygen Delivery • Decrease oxygen demands • Provide analgesia and anxiolytics to relax muscles and avoid shivering • Maintain arterial oxygen saturation/content • Give supplemental oxygen • Maintain Hemoglobin > 10 g/dL • Serial lactate levels or central venous oxygen saturations to assess tissue oxygen extraction End Points of Resuscitation • Goal of resuscitation is to maximize survival and minimize morbidity • Use objective hemodynamic and physiologic values to guide therapy • Goal directed approach • • • • Urine output > 0.5 mL/kg/hr CVP 8-12 mmHg MAP 65 to 90 mmHg Central venous oxygen concentration > 70% Persistent Hypotension • • • • • • Inadequate volume resuscitation Pneumothorax Cardiac tamponade Hidden bleeding Adrenal insufficiency Medication allergy Practically Speaking…. • Keep one eye on these patients • Frequent vitals signs: • Monitor success of therapies • Watch for decompensated shock • Let your nurses know that these patients are sick! Types of Shock • • • • • • • Hypovolemic Cardiogenic Septic Anaphylactic Neurogenic Endocrine Obstructive What Type of Shock is This? • 68 yo M with hx of HTN and DM presents to the ER with abrupt onset of diffuse abdominal pain with radiation to his low back. The pt is hypotensive, tachycardic, afebrile, with cool but dry skin Hypovolemic Shock Types of Shock • Hypovolemic • Septic • Cardiogenic • Anaphylactic • Neurogenic • Obstructive Hypovolemic Shock Hypovolemic Shock • Non-hemorrhagic • • • • • Vomiting Diarrhea Bowel obstruction, pancreatitis Burns Neglect, environmental (dehydration) • Hemorrhagic • • • • • GI bleed Trauma Massive hemoptysis AAA rupture Ectopic pregnancy, post-partum bleeding Hypovolemic Shock • ABCs • Establish 2 large bore IVs or a central line • Crystalloids • Normal Saline or Lactate Ringers • Up to 3 liters • PRBCs • O negative or cross matched • Control any bleeding • Arrange definitive treatment Evaluation of Hypovolemic Shock • • • • • • CBC ABG/lactate Electrolytes BUN, Creatinine Coagulation studies Type and cross-match • As indicated • • • • • • • CXR Pelvic x-ray Abd/pelvis CT Chest CT GI endoscopy Bronchoscopy Vascular radiology Infusion Rates Access 18 g peripheral IV 16 g peripheral IV 14 g peripheral IV 8.5 Fr CV cordis Gravity 50 mL/min 100 mL/min 150 mL/min 200 mL/min Pressure 150 mL/min 225 mL/min 275 mL/min 450 mL/min What Type of Shock is This? • Types of Shock An 81 yo F resident of a nursing home presents to the ED with altered mental • Hypovolemic status. She is febrile to 39.4, • Septic hypotensive with a widened pulse pressure, tachycardic, with warm • Cardiogenic extremities • Anaphylactic • Neurogenic Septic • Obstructive Septic Shock Sepsis • Two or more of SIRS criteria • • • • Temp > 38 or < 36 C HR > 90 RR > 20 WBC > 12,000 or < 4,000 • Plus the presumed existence of infection • Blood pressure can be normal! Septic Shock • Sepsis (remember definition?) • Plus refractory hypotension • After bolus of 20-40 mL/Kg patient still has one of the following: • SBP < 90 mm Hg • MAP < 65 mm Hg • Decrease of 40 mm Hg from baseline Sepsis Pathogenesis of Sepsis Nguyen H et al. Severe Sepsis and Septic-Shock: Review of the Literature and Emergency Department Management Guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;42:28-54. Septic Shock • Clinical signs: • • • • • Hyperthermia or hypothermia Tachycardia Wide pulse pressure Low blood pressure (SBP<90) Mental status changes • Beware of compensated shock! • Blood pressure may be “normal” Ancillary Studies • • • • • • • Cardiac monitor Pulse oximetry CBC, Chem 7, coags, LFTs, lipase, UA ABG with lactate Blood culture x 2, urine culture CXR Foley catheter (why do you need this?) Treatment of Septic Shock • 2 large bore IVs • NS IVF bolus- 1-2 L wide open (if no contraindications) • Supplemental oxygen • Empiric antibiotics, based on suspected source, as soon as possible Treatment of Sepsis • Antibiotics- Survival correlates with how quickly the correct drug was given • Cover gram positive and gram negative bacteria • Zosyn 3.375 grams IV and ceftriaxone 1 gram IV or • Imipenem 1 gram IV • Add additional coverage as indicated • Pseudomonas- Gentamicin or Cefepime • MRSA- Vancomycin • Intra-abdominal or head/neck anaerobic infections- Clindamycin or Metronidazole • Asplenic- Ceftriaxone for N. meningitidis, H. infuenzae • Neutropenic – Cefepime or Imipenem Persistent Hypotension • If no response after 2-3 L IVF, start a vasopressor (norepinephrine, dopamine, etc) and titrate to effect • Goal: MAP > 60 • Consider adrenal insufficiency: hydrocortisone 100 mg IV Treatment Algorithm Rivers E et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock N Engl J Med. 2001:345:1368-1377. What Type of Shock is This? • A 55 yo M with hx of HTN, DM presents with “crushing” substernal CP, diaphoresis, hypotension, tachycardia and cool, clammy extremities Cardiogenic Types of Shock • Hypovolemic • Septic • Cardiogenic • Anaphylactic • Neurogenic • Obstructive Cardiogenic Shock Cardiogenic Shock • Defined as: • SBP < 90 mmHg • CI < 2.2 L/m/m2 • PCWP > 18 mmHg • Signs: • • • • • • Cool, mottled skin Tachypnea Hypotension Altered mental status Narrowed pulse pressure Rales, murmur Etiologies • What are some causes of cardiogenic shock? • • • • • • AMI Sepsis Myocarditis Myocardial contusion Aortic or mitral stenosis, HCM Acute aortic insufficiency Pathophysiology of Cardiogenic Shock • Often after ischemia, loss of LV function • Lose 40% of LV clinical shock ensues • CO reduction = lactic acidosis, hypoxia • Stroke volume is reduced • Tachycardia develops as compensation • Ischemia and infarction worsens Ancillary Tests • EKG • CXR • CBC, Chem 10, cardiac enzymes, coagulation studies • Echocardiogram Treatment of Cardiogenic Shock • Goals- Airway stability and improving myocardial pump function • Cardiac monitor, pulse oximetry • Supplemental oxygen, IV access • Intubation will decrease preload and result in hypotension • Be prepared to give fluid bolus Treatment of Cardiogenic Shock • AMI • Aspirin, beta blocker, morphine, heparin • If no pulmonary edema, IV fluid challenge • If pulmonary edema • Dopamine – will ↑ HR and thus cardiac work • Dobutamine – May drop blood pressure • Combination therapy may be more effective • PCI or thrombolytics • RV infarct • Fluids and Dobutamine (no NTG) • Acute mitral regurgitation or VSD • Pressors (Dobutamine and Nitroprusside) What Type of Shock is This? • Types of Shock A 34 yo F presents to the ER after dining • Hypovolemic at a restaurant where shortly after eating the first few bites of her meal, became • Septic anxious, diaphoretic, began wheezing, noted diffuse pruritic rash, nausea, and a • Cardiogenic sensation of her “throat closing off”. She is currently hypotensive, tachycardic and • Anaphylactic ill appearing. • Neurogenic • Obstructive Anaphalactic Anaphalactic Shock Anaphylactic Shock • Anaphylaxis – a severe systemic hypersensitivity reaction characterized by multisystem involvement • IgE mediated • Anaphylactoid reaction – clinically indistinguishable from anaphylaxis, do not require a sensitizing exposure • Not IgE mediated Anaphylactic Shock • What are some symptoms of anaphylaxis? • First- Pruritus, flushing, urticaria appear •Next- Throat fullness, anxiety, chest tightness, shortness of breath and lightheadedness •Finally- Altered mental status, respiratory distress and circulatory collapse Anaphylactic Shock • Risk factors for fatal anaphylaxis • Poorly controlled asthma • Previous anaphylaxis • Reoccurrence rates • 40-60% for insect stings • 20-40% for radiocontrast agents • 10-20% for penicillin • Most common causes • Antibiotics • Insects • Food Anaphylactic Shock • • • • Mild, localized urticaria can progress to full anaphylaxis Symptoms usually begin within 60 minutes of exposure Faster the onset of symptoms = more severe reaction Biphasic phenomenon occurs in up to 20% of patients • Symptoms return 3-4 hours after initial reaction has cleared • A “lump in my throat” and “hoarseness” heralds lifethreatening laryngeal edema Anaphylactic Shock- Diagnosis • Clinical diagnosis • Defined by airway compromise, hypotension, or involvement of cutaneous, respiratory, or GI systems • Look for exposure to drug, food, or insect • Labs have no role Anaphylactic Shock- Treatment • ABC’s • Angioedema and respiratory compromise require immediate intubation • • • • IV, cardiac monitor, pulse oximetry IVFs, oxygen Epinephrine Second line • Corticosteriods • H1 and H2 blockers Anaphylactic Shock- Treatment • Epinephrine • 0.3 mg IM of 1:1000 (epi-pen) • Repeat every 5-10 min as needed • Caution with patients taking beta blockers- can cause severe hypertension due to unopposed alpha stimulation • For CV collapse, 1 mg IV of 1:10,000 • If refractory, start IV drip Anaphylactic Shock - Treatment • Corticosteroids • Methylprednisolone 125 mg IV • Prednisone 60 mg PO • Antihistamines • H1 blocker- Diphenhydramine 25-50 mg IV • H2 blocker- Ranitidine 50 mg IV • Bronchodilators • Albuterol nebulizer • Atrovent nebulizer • Magnesium sulfate 2 g IV over 20 minutes • Glucagon • For patients taking beta blockers and with refractory hypotension • 1 mg IV q5 minutes until hypotension resolves Anaphylactic Shock - Disposition • All patients who receive epinephrine should be observed for 4-6 hours • If symptom free, discharge home • If on beta blockers or h/o severe reaction in past, consider admission What Type of Shock is This? • Types of Shock A 41 yo M presents to the ER after an MVC complaining of decreased • Hypovolemic sensation below his waist and is now • Septic hypotensive, bradycardic, with warm extremities • Cardiogenic • Anaphylactic • Neurogenic • Obstructive Neurogenic Neurogenic Shock Neurogenic Shock • Occurs after acute spinal cord injury • Sympathetic outflow is disrupted leaving unopposed vagal tone • Results in hypotension and bradycardia • Spinal shock- temporary loss of spinal reflex activity below a total or near total spinal cord injury (not the same as neurogenic shock, the terms are not interchangeable) Neurogenic Shock • Loss of sympathetic tone results in warm and dry skin • Shock usually lasts from 1 to 3 weeks • Any injury above T1 can disrupt the entire sympathetic system • Higher injuries = worse paralysis Neurogenic Shock- Treatment • A,B,Cs • Remember c-spine precautions • Fluid resuscitation • Keep MAP at 85-90 mm Hg for first 7 days • Thought to minimize secondary cord injury • If crystalloid is insufficient use vasopressors • Search for other causes of hypotension • For bradycardia • Atropine • Pacemaker Neurogenic Shock- Treatment • Methylprednisolone • • • • Used only for blunt spinal cord injury High dose therapy for 23 hours Must be started within 8 hours Controversial- Risk for infection, GI bleed What Type of Shock is This? • A 24 yo M presents to the ED after an MVC c/o chest pain and difficulty breathing. On PE, you note the pt to be tachycardic, hypotensive, hypoxic, and with decreased breath sounds on left Obstructive Types of Shock • Hypovolemic • Septic • Cardiogenic • Anaphylactic • Neurogenic • Obstructive Obstructive Shock Obstructive Shock • Tension pneumothorax • Air trapped in pleural space with 1 way valve, air/pressure builds up • Mediastinum shifted impeding venous return • Chest pain, SOB, decreased breath sounds • No tests needed! • Rx: Needle decompression, chest tube Obstructive Shock • Cardiac tamponade • Blood in pericardial sac prevents venous return to and contraction of heart • Related to trauma, pericarditis, MI • Beck’s triad: hypotension, muffled heart sounds, JVD • Diagnosis: large heart CXR, echo • Rx: Pericardiocentisis Obstructive Shock • Pulmonary embolism • • • • • Virscow triad: hypercoaguable, venous injury, venostasis Signs: Tachypnea, tachycardia, hypoxia Low risk: D-dimer Higher risk: CT chest or VQ scan Rx: Heparin, consider thrombolytics Obstructive Shock • Aortic stenosis • Resistance to systolic ejection causes decreased cardiac function • Chest pain with syncope • Systolic ejection murmur • Diagnosed with echo • Vasodilators (NTG) will drop pressure! • Rx: Valve surgery FLUID THERAPY Fluid and electrolyte balance is an extremely complicated thing. Importance Need to make a decision regarding fluids in pretty much every hospitalized patient. Aggressive IV fluids are recommended in most types of shock eg. 1-2 litres of NS bolus over 10mins or 20ml/kg in a child Can be life-saving in certain conditions Choice of IV fluid whether crystalloid or colloid is superior: remains undetermined For persistent shock after initial resuscitation, packed RBCs should be given to keep Hb% > 100gms loss of body water, whether acute or chronic, can cause a range of problems from mild lightheadedness to convulsions, coma, and in some cases, death. Though fluid therapy can be a lifesaver, it's never innocuous, and can be very harmful. Permissive hypotension: For haemorrhagic shock current evidence supports that, limiting the use of fluids for penetrating thorax and abdominal injuries allowing mild hypotension. (Target: MAP of 60mmHg, SBP: 70-90 mmHg Kinds of IV Fluid solutions Hypotonic - 1/2NS Isotonic - NS, LR, albumen Hypertonic – Hypertonic saline. Crystalloid Colloid Crystalloid vs Colloid Type of particles (large or small) Fluids with small “crystalizable” particles like NaCl are called crystalloids Fluids with large particles like albumin are called colloids, these don’t (quickly) fit through vascular pores, so they stay in the circulation and much smaller amounts can be used for same volume expansion. (250ml Albumin = 4 L NS) Edema resulting from these also tends to stick around longer for same reason. Albumin can also trigger anaphylaxis. There are two components to fluid therapy: Maintenance therapy replaces normal ongoing losses, and Replacement therapy corrects any existing water and electrolyte deficits. Maintenance therapy Maintenance therapy is usually undertaken when the individual is not expected to eat or drink normally for a longer time (eg, perioperatively or on a ventilator). Big picture: Most people are “NPO” for 12 hours each day. Patients who won’t eat for one to two weeks should be considered for parenteral or enteral nutrition. Maintenance Requirements can be broken into water and electrolyte requirements: Water — Two liters of water per day are generally sufficient for adults; Most of this minimum intake is usually derived from the water content of food and the water of oxidation, therefore it has been estimated that only 500ml of water needs be imbibed given normal diet and no increased losses. These sources of water are markedly reduced in patients who are not eating and so must be replaced by maintenance fluids. water requirements increase with: fever, sweating, burns, tachypnea, surgical drains, polyuria, or ongoing significant gastrointestinal losses. For example, water requirements increase by 100 to 150 mL/day for each C degree of body temperature elevation. Several formulas can be used to calculate maintenance fluid rates. 4/2/1 rule a.k.a Weight+40 I prefer the 4/2/1 rule (with a 120 mL/h limit) because it is the same as for pediatrics. 4/2/1 rule 4 ml/kg/hr for first 10 kg (=40ml/hr) then 2 ml/kg/hr for next 10 kg (=20ml/hr) then 1 ml/kg/hr for any kgs over that This always gives 60ml/hr for first 20 kg then you add 1 ml/kg/hr for each kg over 20 kg This boils down to: Weight in kg + 40 = Maintenance IV rate/hour. For any person weighing more than 20kg What to put in the fluids Start: D5 1/2NS+20 meq K @ Wt+40/hr a reasonable approach is to start 1/2 normal saline to which 20 meq of potassium chloride is added per liter. (1/2NS+20 K @ Wt+40/hr) Glucose in the form of dextrose (D5) can be added to provide some calories while the patient is NPO. The normal kidney can maintain sodium and potassium balance over a wide range of intakes. So,start: D5 1/2NS+20 meq K at a rate equal to their weight + 40ml/hr, but no greater than 120ml/hr. then adjust as needed, see next page. Start D5 1/2NS+20 meq K, then adjust: If sodium falls, increase the concentration (eg, to NS) If sodium rises, decrease the concentration (eg, 1/4NS) If the plasma potassium starts to fall, add more potassium. If things are good, leave things alone. Usually kidneys regulate well, but: Altered homeostasis in the hospital In the hospital, stress, pain, surgery can alter the normal mechanisms. Increased aldosterone, Increased ADH They generally make patients retain more water and salt, increase tendency for edema, and become hypokalemic. Now onto Part 2 of the presentation: Hypovolemia Hypovolemia or FVD is result of water & electrolyte loss Compensatory mechanisms include: Increased sympathetic nervous system stimulation with an increase in heart rate & cardiac contraction; thirst; plus release of ADH & aldosterone Severe case may result in hypovolemic shock or prolonged case may cause renal failure Causes of FVD=hypovolemia: Gastrointestinal losses: N/V/D Renal losses: diuretics Skin or respiratory losses: burns Third-spacing: intestinal obstruction, pancreatitis Replacement therapy. A variety of disorders lead to fluid losses that deplete the extracellular fluid . This can lead to a potentially fatal decrease in tissue perfusion. Fortunately, early diagnosis and treatment can restore normovolemia in almost all cases. There is no easy formula for assessing the degree of hypovolemia. Hypovolemic Shock, the most severe form of hypolemia, is characterized by tachycardia, cold, clammy extremities, cyanosis, a low urine output (usually less than 15 mL/h), and agitation and confusion due to reduced cerebral blood flow. This needs rapid treatment with isotonic fluid boluses (1-2L NS), and assessment and treatment of the underlying cause. But hypovolemia that is less severe and therefore well compensated is more difficult to accurately assess. History for assessing hypovolemia The history can help to determine the presence and etiology of volume depletion. Weight loss! Early complaints include lassitude, easy fatiguability, thirst, muscle cramps, and postural dizziness. More severe fluid loss can lead to abdominal pain, chest pain, or lethargy and confusion due to ischemia of the mesenteric, coronary, or cerebral vascular beds, respectively. Nausea and malaise are the earliest findings of hyponatremia, and may be seen when the plasma sodium concentration falls below 125 to 130 meq/L. This may be followed by headache, lethargy, and obtundation Muscle weakness due to hypokalemia or hyperkalemia Polyuria and polydipsia due to hyperglycemia or severe hypokalemia Lethargy, confusion, seizures, and coma due to hyponatremia, hypernatremia, or hyperglycemia Basic signs of hypovolemia Urine output, less than 30ml/hr Decreased BP, Increase pulse Physical exam for assessing volume physical exam in general is not sensitive or specific acute weight loss; however, obtaining an accurate weight over time may be difficult decreased skin turgor - if you pinch it it stays put dry skin, particularly axilla dry mucus membranes low arterial blood pressure (or relative to patient's usual BP) orthostatic hypotension can occur with significant hypovolemia; but it is also common in euvolemic elderly subjects. decreased intensity of both the Korotkoff sounds (when the blood pressure is being measured with a sphygmomanometer) and the radial pulse ("thready") due to peripheral vasoconstriction. decreased Jugular Venous Pressure The normal venous pressure is 1 to 8 cmH2O, thus, a low value alone may be normal and does not establish the diagnosis of hypovolemia. SIGNS & SYMPTOMS OF Fluid Volume Excess SOB & orthopnea Edema & weight gain Distended neck veins & tachycardia Increased blood pressure Crackles & wheezes pleural effusion Which brings us to: Labnormalities seen with hypovolemia a variety of changes in urine and blood often accompany extracellular volume depletion. In addition to confirming the presence of volume depletion, these changes may provide important clues to the etiology. BUN/Cr BUN/Cr ratio normally around 10 Increase above 20 suggestive of “prerenal state” (rise in BUN without rise in Cr called “prerenal azotemia.”) This happens because with a low pressure head proximal to kidney, because urea (BUN) is resorbed somewhat, and creatinine is secreted somewhat as well Hgb/Hct Acute loss of EC fluid volume causes hemoconcentration (if not due to blood loss) Acute gain of fluid will cause hemodilution of about 1g of hemoglobin (this happens very often.) Plasma Na Decrease in Intravascular volume leads to greater avidity for Na (through aldosterone) AND water (through ADH), So overall, Plasma Na concentration tends to decrease from 140 when hypovolemia present. Urine Na Urine Na – goes down in prerenal states as body tries to hold onto water. Getting a FENa helps correct for urine concentration. Screwed up by lasix. Calculator on PDA or medcalc.com IV Modes of administration Peripheral IV PICC Central Line Intraosseous IV Problem: Extravasation / “Infiltrated” The most sensitive indicator of extravasated fluid or "infiltration" is to transilluminate the skin with a small penlight and look for the enhanced halo of light diffusion in the fluid filled area. Checking flow of infusion does not tell you where the fluid is going Thank you