Output & Expenditure: Aggregate Expenditure Model

Output and Expenditure in the Short Run

Aggregate expenditure (AE)

The total amount of spending on the economy’s output:

Aggregate Expenditure AE = C + I + G + NX

•

Consumption ( C )

• Planned Investment ( I )

•

Government Purchases of Goods + Services ( G )

•

Net Exports ( NX )

Actual investment in a year can differ from planned investment: businesses wind up

“investing” in unintended inventories if sales fall short of what they expected

Macroeconomic Equilibrium: Aggregate Expenditure = Output (Y)

AE = C + I + G + NX = Y

The Aggregate Expenditure Model

Adjustments to Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Actual investment in a year can differ from planned investment: businesses

“invest” in unintended inventories if sales fall short of what they expected

IF … THEN …

Aggregate expenditure is

equal to GDP inventories are unchanged

Aggregate expenditure is

less than GDP inventories rise

Aggregate Expenditure is

greater than GDP inventories fall

AND … the economy is in macroeconomic equilibrium.

GDP and employment decrease.

GDP and employment

increase.

Components of Real Aggregate Expenditure, 2010

Expenditure Category

Consumption

Planned investment

Government purchases

Net exports

Real Expenditure

(billions of 2005 dollars)

$9,221

1,715

2,557

−422

Consumption

Real Consumption

Consumption follows a smooth, upward trend, interrupted only infrequently by brief recessions.

The most important variables that determine the level of C:

•

Current disposable income

• Household wealth: Assets minus liabilities

Including equity in owner occupied houses?

Do Changes in Housing Wealth Affect Consumption Spending?

Housing wealth equals the market value of houses minus the value of loans people have taken out to pay for the houses = Homeowner Equity

The figure shows the

S&P/Case-

Shiller index of housing prices, which represents changes in the prices of singlefamily homes.

Because many macroeconomic variables move together, economists sometimes have difficulty determining whether movements in one are causing movements in another.

The most important variables that determine the level of C:

•

Current disposable income

•

Household wealth: Assets minus liabilities

Including equity in owner occupied houses?

• Expected future income

People try to keep their consumption fairly steady from year-to-year

tie consumption to “permanent income” and save for a rainy day

• The price level

Higher price level reduces real value of monetary wealth

• The interest rate

High interest rate discourages spending on credit/encourages saving

•

New, gotta-have styles and products

The most important determinant of consumption is: a. Current disposable income b. Household wealth.

c. Expected future income.

d. The price level and the interest rate.

The Consumption Function

The Relationship between Consumption and Income, 1960–2010

The Slope of the Consumption Function is the Marginal Propensity to Consume

MPC = Change in Consumption in Response to a Change in Disposable Income

MPC = ΔConsumption/ΔDisposable Income = ΔC/ΔY

D

When disposable income changes,

ΔC = MPC x ΔY

D

For a textbook economy:

The Relationship between Consumption and National Income when net taxes are constant

ΔY

D

= ΔNI

Which of the following is correct?

a. Disposable income is equal to national income plus government transfer payments minus taxes.

b. Taxes minus Government transfer payments equal net taxes.

c. Disposable income = National income – Net taxes.

d. All of the above.

Income, Consumption, and Saving

National income = Consumption + Saving + Net Taxes

Y = C + S + T

Change in NI = Change in consumption + Change in saving + Change in taxes

Y

C

S

T

If taxes are always a constant amount, ΔT = 0

ΔY = ΔC + ΔS

1 = MPC + MPS

Calculating the Marginal Propensity to Consume and the Marginal

Propensity to Save

Fill in the blanks in the following table. For simplicity, assume that taxes are zero.

National Income and Real GDP (Y)

Consumption

(C)

$9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

13,000

$8,000

8,600

9,200

9,800

10,400

Saving

(S)

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC)

—

Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS)

—

Calculating the Marginal Propensity to Consume and the Marginal

Propensity to Save

Fill in the blanks in the following table. For simplicity, assume that taxes are zero.

National Income and Real GDP (Y)

$9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

13,000

Consumption

(C)

$8,000

8,600

9,200

9,800

10,400

Saving

(S)

$1,000

1,400

1,800

2,200

2,600

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC)

—

0.6

Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS)

—

0.4

Fill in the table.

For example, to calculate the value of the MPC in the second row, we have:

MPC

C

Y

$ 8 , 600

$ 8 , 000

$ 10 , 000

$ 9 , 000

$ 600

$ 1 , 000

0 .

6

To calculate the value of the MPS in the second row, we have:

MPS

S

Y

$ 1 , 400

$ 1 , 000

$ 10 , 000

$ 9 , 000

$ 400

$ 1 , 000

0 .

4

Calculating the Marginal Propensity to Consume and the Marginal

Propensity to Save

Fill in the blanks in the following table. For simplicity, assume that taxes are zero.

National Income and Real GDP (Y)

$9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

13,000

Consumption

(C)

$8,000

8,600

9,200

9,800

10,400

Saving

(S)

$1,000

1,400

1,800

2,200

2,600

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC)

—

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS)

—

0.4

0.4

0.4

Show that the MPC plus the MPS equals 1.

Show that the MPC plus the MPS equals 1.

At every level of national income, the MPC is 0.6 and the MPS is 0.4.

Therefore, the MPC plus the MPS is always equal to 1.

If the marginal propensity to consume ( MPC ) is 0.9, how much additional consumption will result from an increase of $80 billion of disposable income?

a. $88.89 billion.

b. $800 billion.

c. $72 billion.

d. None of the above.

Planned Investment

Real Investment

Investment is subject to larger changes than is consumption.

Investment declined significantly during the recessions of 1980, 1981 –1982,

1990 –1991, 2001, and 2007–2009.

Note: The values are quarterly data, seasonally adjusted at an annual rate.

The most important variables that determine the level of investment:

•

Expectations of future profitability

Waves of optimism and pessimism

• Major technology changes: new products & processes

• The interest rate

• Taxes

• Cash flow Retained earnings for financing investment

•

Current capacity utilization

The behavior of consumption and investment over time can be described as follows: a. Investment follows a smooth, upward trend, but consumption is highly volatile.

b. Consumption follows a smooth, upward trend, but investment is subject to significant fluctuations.

c. Both consumption and investment fluctuate significantly over time.

d. Neither consumption nor investment fluctuate significantly over time .

Government Purchases (including State and Local) = G

Real Government Purchases

Government purchases grew steadily for most of the 1979–2011 period, with the exception of the early 1990s, when concern about the federal budget deficit caused real government purchases to fall for three years, beginning in 1992 and in recent recession when State and Local expenditures declined.

Real Net Exports

Net exports were negative in most years between 1979 and 2011.

Net exports have usually increased when the U.S. economy is in recession and decreased when the U.S. economy is expanding, although they fell during most of the 2001 recession.

Note: The values are quarterly data, seasonally adjusted at an annual rate.

Net Exports (NX)

The most important variables that determine the level of net exports:

• The price level in the United States relative to the price levels in other countries

• The growth rate of GDP in the United States relative to the growth rates of GDP in other countries

• The exchange rate between the dollar and other currencies

If inflation in the United States is lower than inflation in other countries, then U.S. exports ________ and U.S. imports ________, which _________ net exports.

a. increase; increase; decreases b. increase; decrease; increases c. decrease; increase; increases d. decrease; increase; decreases

Graphing Macroeconomic Equilibrium

The Relationship between Planned Aggregate

Expenditure and GDP on a 45 °-Line Diagram

Graphing Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Graphing Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Showing a Recession on the 45 °-Line Diagram

Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Real

GDP

(Y)

Consump tion

(C)

Planned

Invest ment

(I)

Govern ment

Purchases

(G)

Net

Export

(NX)

Planned

Aggregate

Expenditur e

(AE)

Unplan ned

Change in Invent ories

Real

GDP

Will …

$8,000

9,000

10000

$6,200

6,850

7,500

$1,500

1,500

1,500

$1,500 – $500

1,500 –500

1,500

$8,700

9,350

10,000

–$700

–350

0 increase increase be in equili brium

11000

12000

8,150

8,800

1,500

1,500

1,500

1,500

–500

–500

–500

10,650

11,300

+350

+700 decrease decrease

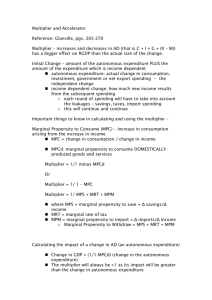

The Multiplier Effect

Learning Objective 11.4

The Multiplier Effect

Autonomous expenditure An expenditure that does not depend on the level of GDP.

Multiplier The increase in equilibrium real GDP in response to increase in autonomous expenditure, e.g.

Expenditure multiplier = ΔY/ΔI

Multiplier effect The process by which an increase in autonomous expenditure leads to a larger increase in real GDP:

ΔY = ΔI + ΔC

= Change in autonomous spending that sparks an expansion

+

Change in consumption spending induced by increasing output and income.

ROUND 1

ROUND 2

ROUND 3

ROUND 4

ROUND 5

.

.

.

ROUND 10

.

.

.

ROUND 15

.

.

.

ROUND 19 n

The Multiplier Effect in Action

ADDITIONAL

AUTONOMOUS

EXPENDITURE

(INVESTMENT)

$100 billion

0

0

0

0

.

.

.

.

.

.

0

0

.

.

.

0

0

ADDITIONAL

INDUCED

EXPENDITURE

(CONSUMPTION)

$0

75 billion

56 billion

42 billion

32 billion

.

.

.

8 billion

.

.

.

2 billion

.

.

.

1 billion

0

TOTAL ADDITIONAL

EXPENDITURE =

TOTAL ADDITIONAL GDP

$100 billion

175 billion

231 billion

273 billion

305 billion

.

.

.

377 billion

.

.

.

395 billion

.

.

.

398 billion

$400 billion

Making the

Connection

The Multiplier in Reverse:

The Great Depression of the 1930s

The multiplier effect contributed to the very high levels of unemployment during the Great

Depression.

Year Consumption Investment Net Exports Real GDP Unemployment Rate

1929 $661 billion $91.3 billion $9.4illion

$865 billion

1933 $541 billion $17.0 billion -$10.2 billion $636 billion

3.2%

24.9%

The Multiplier Effect

A Formula for the Multiplier

1

1

MPC

Y = C + I + G + NX

C depends on Y

D

:

C = c

0

+ MPC x Y

D

= c

0

+ MPC x (Y – T) c

0

, I, G, T, and NX are autonomous—they do not depend on Y

Y = c

0

+ MPC x Y

(1 – MPC) x Y = c

0

– MPC x T + I + G + NX

+ I + G – MPC x T + NX

Y = [1/(1 – MPC)] x [c

0

+ I + G – MPC x T + NX]

Multiplier

Change

Change in in equilibriu autonomous m real GDP expenditur e

1

1

MPC

Find equilibrium GDP using the following macroeconomic model:

C = 1000 + 0.75

I = 500

G = 600

NX

= −300 a.

800 b.

1800 c.

2400 d.

7200

Y

Y = C + I + G + NX

Consumption function

Investment function

Government spending function

Net export function

Equilibrium condition

Summarizing the Multiplier Effect

1

The multiplier effect occurs both when autonomous expenditure increases and when it decreases.

2

The multiplier effect makes the economy more sensitive to changes in autonomous expenditure than it would otherwise be.

3

The larger the MPC , the larger the value of the multiplier.

4

The formula for the multiplier, 1/(1 −

MPC ), is oversimplified because it ignores some real-world complications, such as the effect that an increasing GDP can have on taxes, imports, prices and interest rates.

Using the Multiplier Formula

Use the information in the table to answer the following questions:

Real GDP

(Y)

$8,000

9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

Consumption

(C)

$6,900

7,700

8,500

9,300

10,100

Planned

Investment

(I)

$1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

Note: The values are in billions of 2005 dollars.

Government

Purchases

(G)

$1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

Net Exports

(NX)

−$500

−500

−500

−500

−500 a . What is the equilibrium level of real GDP?

b . What is the MPC ?

c . If government purchases increase by $200 billion, what will be the new equilibrium level of real GDP?

Use the multiplier formula to determine your answer.

Using the Multiplier Formula

Use the information in the table to answer the following questions:

Real GDP

(Y)

$8,000

9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

Consumption

(C)

$6,900

7,700

8,500

9,300

10,100

Planned

Investment

(I)

$1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

Government

Purchases

(G)

$1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

1,000

Net Exports

(NX)

−$500

−500

−500

−500

−500

Planned

Aggregate

Expenditure

(AE)

$8,400

9,200

10,000

10,800

11,600

Note: The values are in billions of 2005 dollars.

Determine equilibrium real GDP.

We can find macroeconomic equilibrium by calculating the level of planned aggregate expenditure for each level of real GDP.

We can see that macroeconomic equilibrium will occur when real GDP equals $10,000 billion.

Calculate the MPC.

MPC

C

Y

In this case: MPC

$800 billion

$1,000 billion

0 .

8

Using the Multiplier Formula

Use the multiplier formula to calculate the new equilibrium level of real

GDP.

We could find the new level of equilibrium real GDP by constructing a new table with government purchases increased from $1,000 billion to $1,200 billion.

But the multiplier allows us to calculate the answer directly.

In this case:

Multiplier

1

1

MPC

1

1

0 .

8

5

So:

Change in equilibrium real GDP = Change in autonomous expenditure

×

5

Or:

Change in equilibrium real GDP = $200 billion

×

5 = $1,000 billion

Therefore:

New level of equilibrium GDP = $10,000 billion + $1,000 billion

= $11,000 billion

The Paradox of Thrift

In discussing the aggregate expenditure model, John Maynard

Keynes argued that if many households decide at the same time to increase their saving and reduce their spending, they may make themselves worse off by causing aggregate expenditure to fall, thereby pushing the economy into a recession.

The lower incomes in the recession might mean that total saving does not increase, despite the attempts by many individuals to increase their own saving.

Keynes referred to this outcome as the paradox of thrift because what appears to be something favorable to the long-run performance of the economy might be counterproductive in the short run.

Aggregate Demand: The Relation Between Price and Aggregate Expenditure

Increases in the price level cause aggregate expenditure to fall, and decreases in the price level cause aggregate expenditure to rise.

There are three main reasons for this inverse relationship between changes in the price level and changes in aggregate expenditure:

•

A rising price level decreases C onsumption by decreasing the real value of household wealth

•

International competition : If the price level in the United States rises relative to the price levels in other countries, U.S. exports will become relatively more expensive, and foreign imports will become relatively less expensive, causing Net Exports to fall.

•

Interest rate effect : When prices rise, firms and households need more money to finance buying and selling. If the central bank does not increase the money supply, the result will be an increase in the interest rate, which causes I nvestment spending to fall. Rising interest rates may also lead to dollar appreciation: U.S. exports will become relatively more expensive, and foreign imports will become relatively less expensive, causing Net Exports to fall yet more.

The Aggregate Demand Curve

The Effect of a Change in the Price Level on Real GDP

Aggregate demand curve A curve that shows the relationship between the price level and the level of planned aggregate expenditure, holding constant all other factors that affect aggregate expenditure.

K e y T e r m s

Aggregate demand curve

Aggregate expenditure ( AE )

Aggregate expenditure model

Autonomous expenditure

Cash flow

Consumption function

Inventories

Marginal propensity to consume ( MPC )

Marginal propensity to save ( MPS )

Multiplier

Multiplier effect

Appendix

The Algebra of Macroeconomic Equilibrium

1 C

C

MPC ( Y ) Consumption function

2 I

1 Planned investment function

3 G

G

4 NX

N X

5 Y

C

I

G

NX

Government spending function

Net export function

Equilibrium condition

Appendix

The Algebra of Macroeconomic Equilibrium

The letters with bars over them represent fixed, or autonomous, of 1,000 in our original example. Now, solving for equilibrium, we get:

Y C MPC(Y)

Or,

Y - MPC(Y) C I G NX

Or,

Y (

1

MPC )

NX

Or,

Y

C I G NX

1

MPC

Appendix

The Algebra of Macroeconomic Equilibrium

1

Remember that is the multiplier. Therefore an alternative

1

MPC expression for equilibrium GDP is:

Equilibrium GDP = Autonomous expenditure x Multiplier