SBS Template - Sports Volunteering Research Network

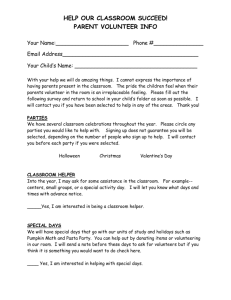

advertisement

‘New volunteerism and reflexive volunteering: From ‘Altruism’ to Altruistic individualism at mega sports events’ Presentation Delivered at the Sports Volunteering Research Network Meeting Wednesday 17th April Northumbria University Konstantinos Tomazos PhD and Sheila Luke BA (Hons) Department of Management, University of Strathclyde Business School Overview Volunteering and mega sports events Traditional approach to volunteering Volunteering and the current context New Volunteerism Altruism and Instrumentalism Reflexive Volunteering The Volunteer Assets Model (VAM) Volunteers and Mega Sports Events A Volunteer labour force is critical to mega sports events such as the Olympic or Commonwealth games (Preuss, 2007: 207) Without volunteers, such events would cease to exist (Goldblatt, 2002: 110) The costs of running such events with paid labour would be prohibitive and, as such events increase in size and number, their reliance on volunteers has grown apace (Nichols and Ralston, 2010:169) 2000 Olympic Games (Sydney): 70,000 volunteers 2002 Commonwealth Games (Manchester): 10,500 volunteers 2012 Olympic Games (London): 70,000 volunteers (required) 2014 Commonwealth Games (Glasgow): 15,000 (required) Traditional Approach to Volunteering Based around the collective and the community (Hustinx and Lammertyn, 2003) Expression of belonging (Ralston et al, 2004) High availability (Meijs and Brudney, 2007) Long term involvement (Rehberg, 2005) Regularly scheduled engagement (Meijs and Brudney, 2007) Related to religious tradition of altruism (Rehberg, 2005) Altruism: “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing another's welfare” (Batson and Shaw, 1991:108) Volunteering in the Current Context Volunteering is taking place amidst changing living conditions and lifestyles (Hustinx et al, 2010). Time Constraints Technological developments Changing working habits Economic downturn Blurring of sectors Globalisation Consumer society Volunteering Changing family unit “New Volunteerism” Challenge of recruiting and retaining volunteers in an era of a decline in civic engagement (Putnam, 1993; Stolle and Hooghe, 2003). • Reinventing the concept of volunteering as “revolving-door”, “drop-by”, or “plug-in” volunteering (Dekker and Halman, 2003; Eliasoph, 1998). • Self-driven and self-centred volunteering could provide a new impetus for an alternative volunteer movement using an army of dedicated individuals serving others while meeting their own needs and writing their own narrative of self-actualization (Micheletti, 2003; Handy and Srinivasan, 2004). Volunteer Motivation Majority of volunteer studies have examined volunteers as a homogeneous group, not taking into account the diversity and proliferation of volunteer activities Imprecise Inconsistent Three-dimension model 1. Material/ Utilitarian 2. Solidary/Affective/Social 3. Purposive/Normative/Altruistic Volunteer Motivations and Mega Sport Events Volunteer motivations at mega sports events are distinct from other forms of volunteering (Farrell et al, 1998; Johnston et al, 2000 ) Memories that will last a lifetime To feel useful Uniqueness of the games To support my nation To attend an Olympic event Feel good factor To give something back (Ralston et al., 2004; Giannoulakis et al, 2008) Prestige The Nature of Altruism It does not make sense, biologically to help others in a competitive environment, because it does little to secure our own survival But… Countless examples in the animal world counteract this perspective (vervet monkeys, vampire bats etc.) Inclusive fitness (Hamilton, 1964) Reciprocal altruism (Trivers, 1971) Highly egotistical ? Strings attached (Mayr, 1988) Seeking admiration and approval from fellow citizens (Alexander, 1987) Engaging in Altruistic Acts It is difficult to move agents who are genetically programmed to be selfish to having concern for others. Humans are programmed with a primitive form of egoism that is based on the care of a small number of prudential values; survival, advancement over others, and gratification (Griffin, 1997) We care for others only to the degree that the well-being of these others affects our own (social egoism) The degree to which we might argue for or against altruism or egoism is a function of the costs that we may incur in the transaction Emotional Basis of Altruism Batson (1990) argued that our capacity for altruistic behaviour/caring towards others hinges on other human traits that are intrinsically pro-social; shame, empathy and guilt. These lead to an immediate pay-off for the altruist (Gintis, 2002) Emotions keep us on track in preventing us from making solely rational decisions in our own best interests based on minimizing costs and maximizing benefits (Frank, 1988; Khalil, 2004) Combining Altruism and Instrumentalism Enlightened Self Interest People join together in groups to further the interests of the group and by that serve their own interests Is it to the advantage of a person to work for a benefit for all? Reciprocity central in altruistic acts Nothing wrong with wanting something in return when acting for the benefit of a cause or others Volunteers can be altruistic individualists Reflexive Volunteering Fundamentally entrenched in the active (re)design of individualised biographies and lifestyles (Hustinx and Lammertyn 2003: 238). • Reflexive volunteers invest a restricted amount of time, and perform a limited set of activities (Hustinx et al, 2010). • Scholars of volunteerism and participation document the assumed ‘passing’ of the traditional volunteer, the emergence and rise of the episodic volunteer (Cnnan and Handy, 2005; Handy, Brodeur and Cnaan, 2006; MacDuff, 2005), an apparent loss of social capital (Putnam, 2000), the emergence of postmodernism (Hustinx and Lammertyn, 2003), and problems of building citizenship and community spirit (Meijs and Brudney, 2007). Have we been using the wrong model of volunteer work? Need to focus on the organisation’s needs and how the potential volunteers’ assets (talents, capabilities, knowledge and expertise) could serve them best. The Volunteer Assets Model Service: Offering high availability but low assets (The traditional backbone of volunteer supply) Star: Offering high availability that host organisations wish to engage precisely to benefit from their assets (high levels of professional training or accomplishment, influence in their community, association with important decision makers) Sweat: Offering low availability and low assets. They include younger volunteers and students engaged in learning who may just be starting work in organisations and lack experience. They could also be highly professional experts who chose to perform outside their chosen career field (i.e doctors preparing meals etc) Specialists: Offering low availability, but have high assets that they may wish to contribute (highly trained professionals spanning different fields). They may not have the opportunity (availability) to contribute these valuable skills on an on-going basis, but are attracted to episodic volunteering. (Devised from the work of Brudney and Meijs, 2009) The VAM in Action… • Volunteer administrators should be encouraged to find a ‘fit’ between a potential volunteer’s interests, needs and motivations and what they as an organisation can offer to them. Getting the correct mix of expectations, motivations and outcomes could really make a difference in terms of a recruitment drive. • Looking at the model, any potential training could turn sweat and service volunteers into specialists, but also the training could be perceived as an added bonus which may affect availability, especially amongst less represented social groups for whom volunteering for 2014 could be the first form of formal training they may have received • Recruitment strategy should communicate to potential volunteers: The context of the work, the time considerations, possible out of pocket costs, the training they offer, the qualifications and characteristics that would be ideal and the benefits to the volunteer. The tasks and the skills needed could make the most use of the ‘stars’ volunteers, so that certain vital skills do not go wasted on the wrong task. Another important aspect is taking care of the costs of volunteering participation and communicating that to the potential participants so that there is no imbalance between the costs and the rewards of the participation. The potential cost could be a potential barrier that perhaps keeps people with low assets away from volunteering for the Games and as such it should become perfectly clear to them that all costs would be covered. Making the Most out of Volunteers The “Volunteer- Fit” Model RECRUITMENT/ SELECTION Matching skills to tasks Inclusivity Volunteer’s Needs and Expectations TRAINING Transferable Skills Accredited Qualification MANAGEMENT Rotation Upholding Enthusiasm Identity Reinforcement THE EVENT Inspiration Community Ethos Change COMMUNICATION Costs Benefits Organization’s Needs and Expectations Glasgow 2014 and the VAM… A Legacy Organization…. Using the Manchester Event Volunteering (MEV) organization (Nichols and Ralston, 2010: p178) as a role model, Glasgow should perhaps set up a similar organization Marketing Recruitment drives Training- Develop a reliable and skilled workforce Accreditation from a training body/ Further education Future Employment Code of Good Practice Effective volunteer management/ Manual Use of Social Media/ Network Branding/ Making Volunteering Cool Effectiveness/ One Voice If all bodies work under the same umbrella organization, then the volunteer legacy agenda could be pushed more effectively References BATSON, C. D. & SHAW, L. L. 1991. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2, 107-122. FARRELL, J. M., JOHNSTON, M. E. & TWYNAM, D. G. 1998. Volunteer motivation, satisfaction, and management at an elite sporting competition. Journal of Sport Management, 12, 288300. GIANNOULAKIS, C., WANG, C.-H. & GRAY, D. 2008. Measuring Volunteer Motivation in MegaSporting Events. Event Management, 11, 191-200. HUSTINX, L., CNAAN, R. A. & HANDY, F. 2010. Navigating Theories of Volunteering: A Hybrid Map for a Complex Phenomenon. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40, 410-434. HUSTINX, L. & LAMMERTYN, F. 2003. Collective and Reflexive Styles of Volunteering: A Sociological Modernization Perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14. MEIJS, L. & BRUDNEY, J. L. 2007. Winning volunteer scenarios: The soul of a new machine. International Journal of Volunteer Administration, 24, 68-79. RALSTON, R., DOWNWARD, P. & LUMSDON, L. 2004. The Expectations of Volunteers Prior to the XVII Commonwealth Games, 2002: A Qualitative Study. Event Management, 9, 13-26. REHBERG, W. 2005. Altruistic Individualists: Motivations for International Volunteering Among Young Adults in Switzerland. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16, 109-122.