Jeffersonian Republicanism

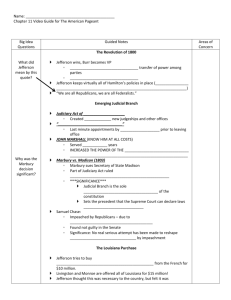

advertisement

The early 19th century was a period rife with conflict and partisan passion. The Jeffersonians attempted to use the impeachment process to rid the federal courts of judges they considered unfit or overly partisan. A former vice president was tried for treason. Britain and France intercepted American ships and confiscated their cargoes. Britain seized naturalized American sailors and forced them into the British navy. Finally, the United States once again waged war with Britain, the world's strongest power. Jefferson in Power previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page Thomas Jefferson's goal as president was to restore the principles of the American Revolution. Not only had the Federalists levied oppressive taxes, stretched the provisions of the Constitution, and established a bastion of wealth and special privilege in the creation of a national bank, they also had subverted civil liberties and expanded the powers of the central government at the expense of the states. A new revolution was necessary, "as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form." What was needed was a return to basic republican principles. On March 4, 1801, Jefferson, clad in clothes of plain cloth, walked from a nearby boarding house to the new United States Capitol in Washington. Without ceremony, he entered the Senate chamber, and took the presidential oath of office. Then, in a weak voice, he delivered his inaugural address--a classic statement of Republican principles. His first concern was to urge conciliation and to allay fear that he planned a Republican reign of terror. "We are all Republicans," he said, "we are all Federalists." Echoing George Washington's Farewell Address, he asked his listeners to set aside partisan and sectional differences and remember that "every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle." Only a proper respect for principles of majority rule and minority rights would allow the new nation to thrive. In the remainder of his address he laid out the principles that would guide his presidency: a frugal, limited government; reduction of the public debt; respect for states' rights; encouragement of agriculture; and a limited role for government in peoples' lives. He committed his administration to repealing taxes, slashing government expenses, cutting military expenditures, and paying off the public debt. Through his personal conduct and public policies he sought to return the country to the principles of Republican simplicity. He introduced the custom of having guests shake hands instead of bowing stiffly; he also placed dinner guests at a round table, so that no individual would have to sit in a more important place than any other. Jefferson refused to ride an elegant coach or host elegant dinner parties and balls and wore clothes made of homespun cloth. To dramatize his disdain for pomp and pageantry, he received the British minister in his dressing gown and slippers. Jefferson believed that presidents should not try to impose their will on Congress, and consequently he refused to openly initiate legislation or to veto congressional bills on policy grounds. Convinced that Presidents Washington and Adams had acted like British monarchs by personally appearing before Congress and requesting legislation, Jefferson simply sent Congress written messages. It would not be until the presidency of Woodrow Wilson that another president would publicly address Congress and call for legislation. Jefferson's commitment to Republican simplicity was matched by his stress on economy in government. He slashed army and navy expenditures, cut the budget, eliminated taxes on whiskey, houses, and slaves, and fired all federal tax collectors. He reduced the army to 3,000 soldiers and 172 officers, the navy to 6 frigates, and foreign embassies to 3 in Britain, France, and Spain. Convinced that ownership of land and honest labor in the earth were the firmest bases of Republican government, Jefferson convinced Congress to cut the price of public lands and to extend credit to purchasers in order to encourage land ownership and rapid western settlement. A firm believer in the idea that America should be the "asylum" for "oppressed humanity," he persuaded Congress to reduce the residence requirement for citizenship from 14 to 5 years. To ensure that the public knew the names and number of all government officials, Jefferson ordered publication of a register of all federal employees. Contemporaries were astonished by the sight of a president who had renounced all the practical tools of government: an army, a navy, and taxes. Jefferson's goal was, indeed, to create a new kind of government, a Republican government wholly unlike the centralized, corrupt, patronageridden one against which Americans had rebelled in 1776. War on the Judiciary previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page When Thomas Jefferson took office, not a single Republican served as a federal judge. He feared that the Federalists intended to use the courts to frustrate Republican plans. The first goal of his presidency was to weaken Federalist control of the federal judiciary. The specific issue that provoked his anger was the Judiciary Act of 1801, which was passed by the lame-duck Federalistdominated Congress five days before Adams's term expired. The law created 16 new federal judgeships, positions which President Adams promptly filled with Federalists. The act reduced the number of Supreme Court justices effective with the next vacancy, delaying Jefferson's opportunity to name a new Supreme Court justice. Jefferson's supporters in Congress repealed the Judiciary Act. William Marbury, who had been appointed to a judgeship by President Adams during his last hours of office, filed suit. Marbury asked the Supreme Court to order the Jefferson administration to give him a formal letter of appointment. The case threatened a direct confrontation between the judiciary and the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. If the Supreme Court ordered Madison to give Marbury his judgeship, the Jefferson administration was likely to ignore the court. John Marshall, the new chief justice of the Supreme Court, was well aware of the court's predicament. When Marshall became the nation's fourth chief justice in 1801, the Supreme Court lacked prestige and public respect. Presidents found it difficult to find willing candidates to serve as justices. The Court was considered so insignificant that it held its sessions in a clerk's office in the basement of the Capitol and only met six weeks a year. In his opinion in Marbury v. Madison, the chief justice ingeniously expanded the court's power without directly provoking the Jeffersonians. Marshall conceded that Marbury had a right to his appointment but ruled the Court had no authority to order the Jefferson administration to act, since the section of the Judiciary Act that gave the Court the power to issue an order was unconstitutional. For the first time, the Supreme Court had declared an act of Congress unconstitutional. Marbury v. Madison was a landmark in American constitutional history. The decision established the power of the federal courts to review the constitutionality of federal laws and to invalidate acts of Congress when they are determined to conflict with the Constitution. This power, known as judicial review, provides the basis for the important place that the Supreme Court occupies in American life today. In fact, the Supreme Court did not invalidate another act of Congress for half a century. Chief Justice Marshall recognized that the judiciary was the weakest of the three branches of government, and in the future the high court refrained from rulings in advance of national sentiment. Marshall's decision in Marbury v. Madison intensified Republican party distrust of the courts. Impeachment, Jefferson believed, was the only way to make the courts responsive to the public will. Federalists responded by accusing the administration of endangering the independence of the federal judiciary. Three weeks before the court handed down its decision in Marbury v. Madison, the Republican-controlled Congress impeached and removed from office a federal district court judge, John Pickering, who was an alcoholic and may have been insane. On the day of Pickering's conviction, the House voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, who had accused the Jeffersonians of being atheists. Chase was put on trial for holding opinions "hurtful to the welfare of the country." The Constitution specified that a judge could only be removed from office for "treason, bribery, or other high crimes," and in a historic decision that helped to guarantee the independence of the judiciary, the Senate voted to acquit Chase. "Impeachment is a farce which will not be tried again," Jefferson announced. Since Chase's acquittal, no further attempts have been made to reshape the federal courts through impeachment. Despite the Republicans' active hostility toward an independent judiciary, the Supreme Court had emerged as a vigorous third branch of government. The Louisiana Purchase previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page In 1800, Spain secretly ceded the Louisiana territory--the area stretching from Canada to the Gulf Coast and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains--to France, which closed the port of New Orleans to American farmers. Westerners, left without a port from which to export their goods, exploded with anger. Many demanded war. The prospect of French control of the Mississippi River alarmed Jefferson. Jefferson feared the establishment of a French colonial empire in North America blocking American expansion. The president sent negotiators to France, with instructions to purchase New Orleans and as much of the Gulf Coast as they could for $2 million. Circumstances played into American hands when France failed to suppress a slave rebellion in Haiti. One hundred thousand slaves, inspired by the French Revolution, had revolted, destroying 1,200 coffee and 200 sugar plantations. In 1800, France sent troops to crush the insurrection and re-conquer Haiti, but they met a determined resistance led by a former slave named Toussaint Louverture. Then, French forces were wiped out by mosquitoes carrying yellow fever. "Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies," Napoleon, the French leader, exclaimed. Without Haiti, Napoleon had little interest in keeping Louisiana. France offered to sell not just New Orleans but all of Louisiana Province. The American negotiators agreed on a price of $15 million, or about 4 cents an acre. In a single stroke, Jefferson doubled the size of the country. To gather information about the geography, natural resources, wildlife, and peoples of Louisiana, President Jefferson dispatched an expedition led by his private secretary Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, a Virginia-born military officer. For 2 years Lewis and Clark led some 30 soldiers and 10 civilians up the Missouri River as far as present-day central North Dakota and then west to the Pacific. Conspiracies previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page The acquisition of Louisiana terrified many Federalists, who feared that the creation of new western states would further dilute their political influence. In the winter of 1803-1804, a group of Federalist congressmen plotted to establish a "Northern Confederacy" consisting of New Jersey, New York, New England, and Canada, to be established with the support of Britain. Alexander Hamilton repudiated this scheme, and the conspirators turned to Vice President Aaron Burr. In return for Federalist support in his campaign for the governorship of New York, Burr was to swing New York into the Northern Confederacy. Burr was badly beaten, in part because of Hamilton's opposition. Incensed and irate, Burr challenged Hamilton to the duel in which the former Treasury Secretary was fatally wounded. Burr was now a ruined politician and a fugitive from the law. In debt, on the edge of bankruptcy, his fortunes at their lowest point, the desperate Burr became involved in a conspiracy for which he would be put on trial for treason. In the spring of 1805, Burr traveled to the West, where he and an old friend, James Wilkinson, commander of United States forces in the Southwest and military governor of Louisiana, hatched a mysterious scheme. It is still uncertain what the conspirators' goal was, since Burr told different stories to different people. Spain's minister believed that Burr planned to set up an independent nation in the Mississippi Valley. Others reported that he planned to seize Spanish territory in what is now Texas, California, and New Mexico. The British minister was told that for $500,000 and British naval support, Burr would separate the states and territories west of the Appalachians from the rest of the Union and create an empire with himself as its head. In the fall of 1806, Burr and some 60 schemers traveled down the Ohio River toward New Orleans, perhaps to incite disgruntled French settlers to revolt. Wilkinson, recognizing that the scheme was doomed to failure, sent a letter to President Jefferson betraying Burr. Burr fled, but was apprehended in Mississippi Territory. He was then taken to the Richmond, Virginia, circuit court, where, in 1807, he was tried for treason. Jefferson, convinced that Burr was a dangerous man, wanted a conviction regardless of the evidence. Chief Justice John Marshall, who presided over the trial, was equally eager to discredit Jefferson. Ultimately, Burr was acquitted. The reason for the acquittal was the Constitution's strict definition of treason as "levying war against the United States" or "giving ... aid and comfort" to the nation's enemies. In addition, each overt act of treason had to be attested to by two witnesses. The prosecution was unable to meet this strict standard, and as a result of Burr's acquittal, few future cases of treason have ever been tried in the United States. Was Burr guilty of conspiring to separate the West by force? Probably not. The prosecution's case was extremely weak. It rested largely on the unreliable testimony of co-conspirator James Wilkinson, who was a spy in the way of Spain while serving as a U.S. army commander and governor of Louisiana. What, then, was the purpose of Burr's scheming? It appears likely that the former vice president was planning a filibuster expedition--an unauthorized military attack on Mexico, which was then controlled by Spain. To the end of his life, Burr denied that he had plotted treason against the United States. Asked by one of his closest friends whether he had sought to separate the West from the rest of the nation, Burr responded with an emphatic "No! I would as soon have thought of taking possession of the moon and informing my friends that I intended to divide it among them." The Eagle, the Tiger, and the Shark previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page In 1804, Jefferson was easily reelected, carrying every state except Connecticut and Delaware. His second term began, he later wrote, "without a cloud on the horizon.'' But storm clouds soon gathered as a result of war between Britain and France. In May 1803, just two weeks after Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States, France declared war on Britain. The war lasted 12 years. In 1805, France defeated the armies of Austria and Russia and gained control of much of continental Europe. Napoleon then massed his troops for an invasion of England. But at the battle of Trafalgar off the Spanish coast, the British fleet captured 14,000 French and Spanish sailors. Britain was now master of the seas; but France remained supreme on the land. As part of his overall strategy to bring Britain to its knees, Napoleon closed European ports to British goods and ordered the seizure of any vessel that carried British goods or stopped in a British port. Britain retaliated in 1807 by issuing Orders in Council, which required all ships to land at a British port to obtain a license and pay a tariff. United States shipping was caught in the crossfire. France seized 500 ships and Britain nearly 1,000. The most outrageous violation of America's rights was the British practice of impressment. The British navy desperately needed sailors. Unable to get enough volunteers, the British navy seized impressed men on streets and in taverns. When these efforts failed to muster sufficient men, the British began to stop foreign ships and remove seamen alleged to be British subjects. By 1811, nearly 10,000 American sailors had been forced into the British navy. Some were actually deserters from British ships who made more money sailing on U.S. ships. Outrage over impressment reached a fever pitch in 1807 when the British man-of-war Leopard fired at the American naval frigate Chesapeake, killing three American sailors. British authorities then boarded the American ship and removed 4 sailors, only 1 of whom was really a British subject. The Embargo of 1807 previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page In a desperate attempt to avert war, the United States imposed an embargo on foreign trade. Jefferson regarded the embargo as an idealistic experiment--a moral alternative to war. He believed that economic coercion would convince Britain and France to respect America’s neutral rights. The embargo was an unpopular and costly failure. It hurt the American economy far more than the British or French, and resulted in widespread smuggling. Exports fell from $108 million in 1807 to just $22 million in 1808. Farm prices fell sharply. Shippers also suffered. Harbors filled with idle ships and nearly 30,000 sailors found themselves jobless. Jefferson believed that Americans would cooperate with the embargo out of a sense of patriotism. Instead, smuggling flourished, particularly through Canada. To enforce the embargo, Jefferson took steps that infringed on his most cherished principles: individual liberties and opposition to a strong central government. He mobilized the army and navy to enforce the blockade, and declared the Lake Champlain region of New York, along the Canadian border, in a state of insurrection. Pressure to abandon the embargo mounted, and early in 1809, just 3 days before Jefferson left office, Congress repealed the embargo. In effect for 15 months, the embargo exacted no political concessions from either France or Britain. But it had produced economic hardship, evasion of the law, and political dissension at home. Upset by the failure of his policies, the 65-year-old Jefferson looked forward to his retirement: "Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.'' The problem of defending American rights on the high seas now fell to Jefferson's hand-picked successor, James Madison. In 1809, Congress replaced the failed embargo with the NonIntercourse Act, which reopened trade with all nations except Britain and France. Then in 1810, Congress replaced the Non-Intercourse Act with a new measure, Macon's Bill No. 2. This policy reopened trade with France and Britain. It stated, however, that if either Britain or France agreed to respect America's neutral rights, the United States would immediately stop trade with the other nation. Napoleon seized on this new policy in an effort to entangle the United States in his war with Britain. He announced a repeal of all French restrictions on American trade. Even though France continued to seize American ships and cargoes, President Madison snapped at the bait. In early 1811, he cut off trade with Britain and recalled the American minister. For 19 months, the British went without American trade. Food shortages, mounting unemployment, and increasing inventories of unsold manufactured goods finally convinced Britain to end their restrictions on American trade. But the decision came too late. On June 1, 1812, President Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war. A divided House and Senate concurred. The House voted to declare war on Britain by a vote of 79 to 49; the Senate by a vote of 19 to 13. A Second War of Independence previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page Why did the United States declare war on Britain in 1812? The most loudly voiced grievance was British interference with American rights on the high seas. "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights" was a popular battle cry. But if British harassment of American shipping was the primary motivation for war, why then did the prowar majority in Congress come largely from the South, the West, and the frontier, and not from northeastern ship owners and sailors? Northeastern Federalists regarded war with Britain as a grave mistake. The United States, they feared, could not hope to successfully challenge British supremacy on the seas and the government could not finance a war without bankrupting the country. Southerners and westerners, in contrast, were eager to avenge British insults against American honor. Many westerners and southerners had their eye on expansion, viewing war as an opportunity to add Canada and Spanish-held Florida to the United States. War with Britain also offered another incentive: the possibility of clearing western lands of Indians by removing the Indians' strongest ally--the British. In late 1811, General William Henry Harrison provoked a fight with an Indian alliance at Tippecanoe Creek in Indiana. Since British guns were found on the battlefield, many Americans concluded that Britain was responsible for the incident. Weary of Jefferson and Madison's policy of economic coercion, voters swept 63 out of 142 representatives out of Congress in 1810 and replaced them with young Republicans that Federalists dubbed "War Hawks." Having grown up on tales of heroism during the American Revolution, second-generation Republicans were eager to prove their manhood in a "second war of independence." The War of 1812 previous next Period: 1800s Printable Page The United States was woefully unprepared for war. The army consisted of fewer than 7,000 soldiers, few trained officers, and a navy with just 6 warships. In contrast, Britain had nearly 400 warships. The American strategy called for a three-pronged invasion of Canada and heavy harassment of British shipping. The attack on Canada, however, was a disastrous failure. At Detroit, 2,000 American troops surrendered to a much smaller British and Indian force. An attack across the Niagara River, near Buffalo, resulted in 900 American prisoners of war. Along Lake Champlain, a third army retreated into American territory after failing to cut undefended British supply lines. In 1813 America suffered new failures, including the defeat and capture of the American army in the swamps west of Lake Erie. Only a series of unexpected victories at the end of the year raised American spirits. On September 10, 1813, America won a major naval victory at the Battle of Lake Erie near Put-inBay at the western end of Lake Erie. There, Master-Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, who had built a fleet at Presque Isle (Erie, Pennsylvania) successfully engaged six British ships. Though Perry's flagship, the Lawrence, was disabled in the fighting, he went on to capture the British fleet. He reported his victory with the stirring words, "We have met the enemy and they are ours.'' The Battle of Lake Erie was America's first major victory of the war. It forced the British to abandon Detroit and retreat toward Niagara. On October 5, 1813, Major General William Henry Harrison overtook the retreating British army and their Indian allies at the Thames River. He won a decisive victory in which the Indian leader Tecumseh was killed, thereby ending the fighting strength of the northwestern Indians. In the spring of 1814, Britain defeated Napoleon in Europe, freeing 18,000 veteran British troops to participate in an invasion of the United States. The British planned to invade the United States at three points: upstate New York across the Niagara River and Lake Champlain, the Chesapeake Bay, and New Orleans. The London Times expressed the confident English mood: Oh, may no false liberality, no mistaken lenity, no weak and cowardly policy interpose to save the United States from the blow! Strike! Chastise the savages, for such they are.... Our demands may be couched in a single word--Submission!' At Niagara, however, American forces, outnumbered more than three to one, halted Britain's invasion from the north. Britain then landed 4,000 soldiers on the Chesapeake Bay coast and marched on Washington, D.C., where untrained soldiers lacking uniforms and standard equipment were protecting the capital. The result was chaos. President Madison narrowly escaped capture by British forces. On August 24, 1814, the British humiliated the nation by capturing and burning Washington, D.C. President Madison and his wife Dolley were forced to flee the capital--carrying with them many of the nation's treasures, including the Declaration of Independence and Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington. The British arrived so soon after the president fled that the officers dined on a White House meal that had been prepared for the Madisons and 40 invited guests. Britain's next objective was Baltimore. To reach the city, British warships had to pass the guns of Fort McHenry, manned by 1,000 American soldiers. Waving atop the fort was the largest garrison flag ever designed--30 feet by 42 feet. On September 13, 1814, British warships began a 25-hour bombardment of Fort McHenry. British vessels anchored two miles off shore--close enough so that their guns could hit the fort, but too far for American shells to reach them. All through the night British cannons bombarded Fort McHenry, firing between 1,500 and 1,800 cannon balls at the fort. In the light of the "rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,'' Francis Scott Key, a young lawyer detained on a British ship, saw the American flag waving over the fort. At dawn on September 14, he saw the flag still waving. The Americans had repulsed the British attack, with only 4 soldiers killed and 24 wounded. Key was so moved by the American victory that he wrote a poem entitled "The Star-Spangled Banner" on the back of an old envelope. The song was destined to become the young nation's national anthem. The country still faced grave threats in the South. On January 8, 1815, the British fleet and a battle-tested 10,000-man army finally attacked New Orleans. To defend the city, Jackson assembled a ragtag army, including French pirates, Choctaw Indians, western militia, and freed slaves. Although British forces outnumbered Americans by more than 2 to 1, American artillery and sharpshooters stopped the invasion. American losses totaled only 8 dead and 13 wounded, while British casualties were 2,036. Ironically, American and British negotiators in Ghent, Belgium, had signed the peace treaty ending the War of 1812 two weeks earlier. Britain, convinced that the American war was so difficult and costly that nothing would be gained from further fighting, agreed to return to the conditions that existed before the war. Left unmentioned in the peace treaty were the issues over which Americans had fought the war-impressment and British interference with American trade. The War’s Significance previous Period: 1800s Printable Page Although often treated as a minor footnote to the bloody European war between France and Britain, the War of 1812 was crucial for the United States. First, it effectively destroyed the Indians' ability to resist American expansion east of the Mississippi River. General Andrew Jackson crushed the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama, while General William Henry Harrison defeated Indians in the Old Northwest at the Battle of the Thames. Abandoned by their British allies, the Indians reluctantly ceded most of their lands north of the Ohio River and in southern and western Alabama to the U.S. government. Second, the war allowed the United States to rewrite its boundaries with Spain and solidify control over the lower Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. Although the United States did not defeat the British Empire, it had fought the world's strongest power to a draw. Spain recognized the significance of this fact, and in 1819 Spanish leaders abandoned Florida and agreed to an American boundary running clear to the Pacific Ocean. Third, the Federalist Party never recovered from its opposition to the war. Many Federalists believed that the War of 1812 was fought to help Napoleon in his struggle against Britain, and they opposed the war by refusing to pay taxes, boycotting war loans, and refusing to furnish troops. In December 1814, delegates from New England gathered in Hartford, Connecticut, where they recommended a series of constitutional amendments to restrict the power of Congress to wage war, regulate commerce, and admit new states. The delegates also supported a one-term president (in order to break the grip of Virginians on the presidency) and abolition of the Three-fifths clause in the Constitution (which increased the political clout of the South), and talked of seceding if they did not get their way. The proposals of the Hartford Convention became public knowledge at the same time as the terms of the Treaty of Ghent and the American victory in the Battle of New Orleans. Euphoria over the war's end led many people to brand the Federalists as traitors. The party never recovered from this stigma and disappeared from national politics.