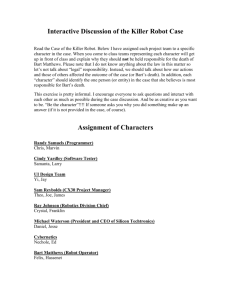

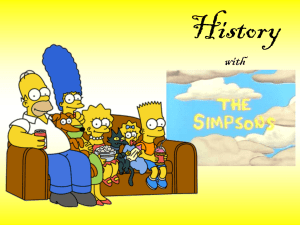

Answers to Questions 1 and 2, Property 2013 final exam Question 1

advertisement

Answers to Questions 1 and 2, Property 2013 final exam Question 1: To determine the property rights involved here, we need to go back to a point in time where known property rights existed. Lisa was the true owner of the disk 15 years ago, and she did not intentionally give up ownership when Bart stole the disk, because she did not form an intention to relinquish ownership or to allow the first finder to acquire ownership rights. Once Bart took the disk, however, he had actual possession, which gives him a superior claim to the disk above all others except the true owner or one to whom the true owner has given the right to possession. Property rights are relative and the true owners’ are superior to the possessor’s. Whether Bart successfully met the elements of adverse possession, in order to defeat Lisa’s claim to return of the disk, depends on the law of Springfield. The elements of adverse possession are continuous (met b/c Bart had control over the disk for 15 years), open (it was known to Lisa, although no one else knew), notorious (known to Lisa that Bart had it and others would have assumed Bart had stolen it given his character), exclusive (met b/c Lisa was excluded from possession), and adverse (clearly possession was hostile to the true owner), for 15 years. Depending on the time period for the running of the S/L, one could determine that A/P was met and Bart would now own the disk, or that it wasn’t met because the open and notorious elements are sketchy. A/P is used to settle expectations and protect possessors against those who sleep on their rights. In that respect, Lisa may lose title. However, A/P is usually not available for those with unclean hands and courts often interpret the elements strictly so as not to allow a thief to acquire title. The majority rule looks to objective aspects of the possessor’s actions and not his state of mind, but a minority of jurisdictions will consider if Bart’s actions were in good faith, or in bad faith. Bart would lose in a good faith state, and would win in a bad faith state, but in an objective state, the issue is open to the court’s interpretation of Bart’s actions. Assuming Bart is deemed to own the disk, the bigger question is whether he is entitled to the papers on the disk. As in INS, courts give quasi-property protections to intellectual property that is not copyrighted (as these papers are not) when public policy demands it and when labor is expended to create it. Lisa certainly expended labor in writing her papers, but it is questionable whether the expression of her ideas should be elevated to the status of property. Because the educational value of writing term papers is in the process of writing, and not the finished product, public policy may dictate that no property right attaches, especially if doing so would allow Lisa to prevent others from writing similar term papers. OTOH, the plagiarism and unjust enrichment that has occurred here suggests that some form of property right should exist in Lisa to prohibit Bart’s exploitation. Few people, however, plan to market their term papers, which suggests that no rule should be created, and we should instead look to equity doctrines like unjust enrichment to solve this dispute. These papers have value because Bart has expended his own labor and investment in modifying the papers and creating a market for them. If this is a valuable market, the law should encourage it by recognizing property rights through accession of value. Although Lisa is the only one (not surprisingly a lawyer) claiming a property right in the paper itself, it is likely that more writers will do so if a market exists and property rights are recognized. Principal Skinner’s claim to the papers is weak. Likely, whatever physical copies of the papers were turned in were abandoned by the students, but they may have retained their intellectual property rights (as stated above). Possession of the papers themselves was then relinquished by Skinner when he licensed Bart to remove and destroy them. However, Skinner likely did not intend for Bart to recycle the papers or take ownership rights in them. As with burial artifacts, the papers held private information about students that could be used in damaging ways and therefore the intention of Skinner to destroy the papers should be protected. Pilfering papers and allowing them to go viral is against Skinner’s intentions and public policies. Although Bart held a profit to remove the papers, he breached the contract by retaining them and potentially defrauded Skinner by exceeding the scope of his permission regarding access to the papers. Lizzy cannot claim that she is a bona fide purchaser of the papers under the common law b/c Bart was a thief and she bought them directly from him. If his website is considered a merchant under the UCC, her rights to possession might be protected, since Lisa could pursue a remedy from Bart the merchant. However, there isn’t a fully developed market in recycled term papers which suggests that Bart is not the kind of merchant the UCC intends to protect, and public policy would suggest that this kind of protection should not be offered. Moreover, Lizzy is not a good faith purchaser, knowing that the paper was not her own intellectual property. Question 2: Bart purchased the outbuilding for his skate shop from Apu subject to numerous restrictions and it is unclear whether Bart obtained an FSCS with a RRE in Apu, or an FSA with an option to purchase in Apu. The provision stating that the land would be forfeited upon payment of the purchase price by either Apu or a neighbor is not a standard estate because it purports to give both the grantor and third parties a future interest. However, the SPEIs given to the neighbors are void under the RAP because the violation of a restriction could occur and a neighbor would exercise the power after the perpetuities period has run. Thus, the rule against the creation of no new estates and the RAP would void the future interests in the neighbors (especially since they are not in privity with the parties). Courts prefer to interpret ambiguous conditions (which is an event the occurrence of which causes transfer of ownership) to be covenants or, in this case, an option to purchase in order to protect the value of the fee in the grantee and protect against unreasonable restraints on alienation. If this is interpreted to be an option to purchase, it may be subject to the RAP as well, if doing so promotes the removal of dead hand control. In this case, because the option entails payment of the purchase price only, and does not account for increases in value or improvements by the grantee, it violates many of the elements of reasonableness that is required of restrictions and conditions. This would suggest that the RAP should be used to terminate the option in APU as well. However, the language and intent of the grant seems clear that what is created is an FSCS with a RRE, which is not subject to the RAP. However, all conditions and restrictions must be reasonable to be enforced, although what constitutes reasonable elements differs between charitable gifts and purchases, or between residential and commercial properties. As stated above, the requirement that only the purchase price be paid argues against the reasonableness of this condition. Thus, in keeping with the presumptions against forfeitures, that the grantor conveyed all of his interests unless clearly retained, and against unreasonable restraints on alienation, it would be reasonable to strike the repurchase language making the interest in Bart an FSA with covenants enforceable through an injunction or damages rather than forfeiture. The covenant against competition must be reasonable. In the commercial context validity rests on the duration of the covenant, and the area and activities constrained, and it must promote orderly and harmonious development. Here the sale of food in competition with the KEM imposes a small disadvantage on Bart’s skate shop but provides a large benefit to Apu. The price of the building probably also accounted for the constraint, and certainly the area is small (just Bart’s store, not all of Bart’s potential properties anywhere in Springfield). The 50-year duration is not unusual given the average lifespan of a commercial establishment. If enforceable, Bart can be enjoined from selling Gatorade or power bars, and licensing the food vendors as well. The grantor consent clause is a restraint on alienation that must be reasonable as well. In the context of a grant of FSA, courts often strike direct restraints because they are repugnant to the fee. Although the grantor binds himself to act reasonably, the restraint is only partial, but this kind of restraint is more common in cases where the grantor/grantee have comingled property interests (as with co-ops or condos). Since Apu and Bart share a parking lot and are very close neighbors, this restraint is more likely to be reasonable than if the properties were simply adjacent. The inter-dependence of the properties makes protecting the grantor more reasonable, although enforcement of the covenant against competition may vitiate the need for the grantor consent clause, arguing against its enforceability. The provision stating the use of the property as a skate shop may be seen as precatory. As in Wood, courts do not find a FSD where a grant only states the purpose of the grant, and does not provide triggering events and giftover language. Only if the language is excruciatingly clear that the grant is premised on the limitation of purpose will a FSCS or FSD be found. The restrictions not to interfere with neighboring uses is enforceable in nuisance law anyway and therefore is part of all grants, and is generally not sufficient to knock an FSA down to something less. The parking lot is another problem. Assuming the outbuilding is landlocked, Bart and his customers must have access to the building. This can be through the parking lot or through a sidewalk from the public street, and will be implied by necessity. Because there is unity of title, severance, and necessity, the access should be granted regardless of the silence of the deed. Whether the access means Bart or his customers can park in the lot is a different matter. It is possible that the parking lot was used to provide parking for suppliers who delivered to the outbuilding and that an easement by prior use could be implied. The fact that the parking lot visibly served both buildings and is reasonably convenient for the outbuilding, and there was unity of title and severance, would suggest that an easement by prior use existed and passed to Bart. The easement would be appurtenant because it is an ingress/egress easement and thus binds both successors to Bart and Apu. Although a skate shop would logically entail skating customers and not driving customers, the expectations of the parties is that some customers will drive and park to access Bart’s shop. Even if the elements of prior use are not strictly met, it is plausible that Bart will have acquired an easement by estoppel because Apu allowed Bart and his customers to use the parking lot and stood by while Bart invested in the shop and the half-pipe. If Apu were to revoke the license to the parking lot, he would likely take ownership of the half-pipe which is an expensive fixture invested on Apu’s land. However, the mere existence of an easement for access to Bart’s shop does not give the dominant estate holder the right to exceed the scope of the easement (by using it for a farmer’s market or for skate-board entertainment) or to unduly burden the easement (by having too many skate-boarders or parkers). Easements implied by law or by equity are limited to what is reasonable and likely to have been intended by the parties in contemplation of the uses to be made of the property. Apu’s closing of the easement violated Bart’s rights to ingress and egress, but was valid to the extent it prevented the burdensome and unreasonable use of the servient estate. The farmer’s market vendors have licenses from Bart to set up around his shop – although this may be on land actually owned by Apu, Bart has an easement and may subdivide his easement as he sees fit subject to limitations of scope and burden. These are not likely to be leases as they do not provide a particular space for each vendor or provide a set amount of rent. As licenses, they are revocable unless the vendors have reasonably relied on them and made investments that would be unreasonably harmed if the license is revoked. Bart’s actions to annoy Apu would seem to be unreasonable and substantial, thus violating the doctrine of sic utere and entailing a nuisance that can be enjoined. Malice alone is never a sufficient justification for imposing harm on neighboring property. Thus, the defaming signs have no justification. The farmer’s market and jazz bands all serve to improve Bart’s business, but they violate the covenant against competition and overrun Apu’s parking lot with vendors and customers, thus infringing on Apu’s property rights to control his parking lot. The harm to Apu is substantial, but whether or not it is unreasonable depends on a variety of factors. Apu was there first, Apu’s use is quiet, the consideration for the outbuilding depended on not competing with Apu, Bart’s actions are in part motivated by spite, and the public benefits could be reaped elsewhere without imposing the harm. If a nuisance is found, Apu would be entitled to an injunction or damages, depending on the equities. The same is true for Mr. Burns whose private residence is being overrun with trespassers. His quiet enjoyment of his home is jeopardized by the music and picnickers, giving him a better claim of nuisance against Bart than Apu has because he has a greater expectation of quiet and privacy in a residential use, and he would have a trespass action against any picnickers on his lawn who intentionally invaded his right to exclude. Whether he could sue Bart or Apu for the trespass is unlikely given the fact that neither actually trespassed on his lawn. However, under nuisance, damages could include all reasonable damages incurred from the farmers market, which would cover the rhododendrons and the trespassers. If a court were to determine that the farmers market was not a nuisance but that substantial harm was occurring to neighboring residential properties, it could order damages for the loss in market value ala Boomer. Finally, it must be determined if Apu Jr. can step into Apu’s shoes to enforce any of the covenants in the deed. As owner of the KEM, Jr. can bring suit for undue burden on the easement or nuisance. But he can only enforce provisions of the deed to Bart if the covenants run with the land. To run, you need writing (met), notice (met), intent (Apu certainly would want the covenants to run to his successors and against Bart’s successors so it can reasonably be assumed). Privity is met horizontally between Bart and Apu Sr., and vertically between Sr. and Jr. who acquired all of Sr’s interest in the KEM by inheritance. Although simultaneous horizontal privity does not exist between Apu and Bart if Bart acquired an FSA with covenants and not an FSCS, instantaneous privity does exist, and most states have moved toward this relaxed formal element. All covenants used to require touch and concern for the covenant to run and noncompetes generally did not touch and concern. However, the modern trend is to interpret non-competes as touching because they affect the fair market value of the land, and because the parties reasonably negotiated and intended the benefit. If it promotes orderly and harmonious development, non-competes are generally deemed to be reasonable and courts have determined that it makes little sense to impose formal easement-like requirements of touching when modern commercial development is different. Even if there is no privity, Jr. can enforce the covenants through an injunction. Finally, there is possible public accommodation issue here – Apu cannot exclude members of the public on the basis of illegal discriminatory categories. Depending on whether age is a protected class, Apu might be unable to exclude the skate-boarding kids on the parking lot if the lot is open to the public.