2305-Fed10 - The Weaker Party

advertisement

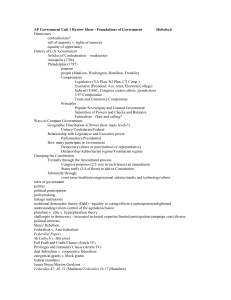

GOVT 2305 Federalist #10 and the Republicanism In the previous section we looked over the nature of Constitutions and analyzed the broad design of the United States Constitution, as well as the alleged failures of the Articles of Confederation. This section is the first of a few where we dig deeper into specific design features within the United States Constitution. We will look separately at these four principles: Republicanism Separated Powers Individual Liberty Federalism This week: Republicanism In other words: Indirect Democracy or Representative Democracy For a reminder: What is a Republic Again? A republic is a type of government where the citizens choose the leaders of their country and the people (or at least a part of its people) have an impact on its government. -Wikipedia More specifically, it means that the preferences of the general population are filtered through representative institutions. Try to memorize the “filter” as an analogy. In brief, a republic attempts to filter out short-term, unstable, radical ideas in order to ensure that the actions of government reflect long term, stable concerns. As we will see, the principle concern by the framers of the Constitution was that powerful, permanent majorities would be able to control all aspects of governing power, become tyrannical, and disregard the rights of the majority. In short: a republic is argued to be better able to prevent the tyranny of the majority. In a republic, people do not rule directly, as in the Athenian democracy, rather they do so though elected representatives. Read Pericles on Athenian Democracy here. We will consider this topic by reading through Federalist #10 which argues that the Constitution successfully limit the dangers posed by factions motivated by personal, narrow interests, not the overall interests of the nation. It does so by filtering their preferences through a legislative system that will break apart majority factions. Please note that I expect you read through Federalist #10 and be prepared to answer a handful of questions regarding its text. Text Wikipedia GradeSaver SparkNotes A faction, as the term was used by Madison, is similar to what we would call today interest (or advocacy) groups. As we will see, the Constitution is designed in part to impact how groups form in the nation and how capable those groups are to creating instability. Consequently, this allows us to take an early look at interest groups, what they are, how they form, and how they are – or are not – effective. At root, this section concerns a conflict that exists between the concept of popular sovereignty and democracy. While we know from our discussion of natural rights that a government must rest on the people, history tells us that the people can provide an unstable basis for government. Classical authors argued that democracies inevitably turned chaotic and out the chaos emerged a tyranny that would keep the peace. Read criticism of the Athenian democracy here. The Framers of the Constitution were aware of these arguments. The democratic system was believed to be the reason Greece was defeated in the Peloponnesian War. A democratic assembly was also responsible for the execution of Socrates. Hamilton, in Federalist #9, stated: “It is impossible to read the history of the petty republics of Greece and Italy without feeling sensations of horror and disgust at the distractions with which they were continually agitated, and at the rapid succession of revolutions by which they were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy.” The framers of the Constitution were also aware that being wealthy property owners, they were in a minority. A democratic majority could take their property, which they saw as a violation of their unalienable rights. Recall the tension between majority rule and minority rights. In a democracy the nature of minority rights can be defined by the majority. The real problem, as the framers of the Constitution saw it, lied in human nature. As we will see later, Madison thought we far more likely to “vex and oppress” each other than to cooperate. This would be fatal in a direct democracy, but manageable in an indirect democracy. A tyrannical system can suppress divisions in society because they are powerful and ruthless enough to eradicate them. Stalin, for example, dealt with opposition groups by killing them. That’s one way to solve the problem. Democracies, which naturally require a degree of individual freedom, allow these divisions to take center stage and lead to conflict. Utter chaos – civil wars – can lead some to conclude that a tyrannical leader is preferable to random violence. This was Thomas Hobbes conclusion in The Leviathan, written during the British Civil Wars. Democracy can lead to tyranny. Tyranny of the Majority The word “democracy” therefore wasn’t a compliment. Think about how people use the term “socialism” today, it was similar. The goal of the U.S. Constitution is to maintain popular rule, to ensure that it did not crumble into tyranny. The question was how. Madison would argue that the answer to these problems was in designing a “well-constructed union.” This would involve creating a republic with strong independent but accountable legislative institutions that rest between the people and the law. So while it is true that the U.S. is a democracy, the democratic design is such that the electorate has a no capacity to instantaneously change policy. While the Preamble begins with “We the People,” much of the remainder of the U.S. Constitution protects government from the people. That is what a republic does. Before we continue, let’s recall what “democracy” means. It means, in Greek, rule of the people, and as is practiced today has three main components. We introduced these previously. 1 - Universal Adult Suffrage 2 - Majority Rule 3 - Minority Rights Obviously we can question whether the U.S. qualified as a democracy at that point given restrictions on suffrage. We discuss these in the section on elections. For now it is important to know that restricted suffrage was a deliberate choice by the framers. The framers of the Constitution were worried about the excesses of democracy, and sought instead to limit the direct impact of the population, while still retaining the basic democratic framework. “The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy.” – Elbridge Gerry He was referring to the problems the nations was allegedly suffering from under the Articles of Confederation. From the Constitutional Convention: Mr. HAMILTON. This question has already been considered in several points of view. We are now forming a republican government. Real liberty is neither found in despotism nor the extremes of democracy, but in moderate governments. The people who attended the Constitutional Convention believed that the policies proposed by the democratic legislatures in the states were harmful to the future stability of the union. The legislatures were, for example, debasing currency to allow for easier payments of debt even though this policy, in their opinion, harmed long term economic development. James Madison would mention these specifically in the latter parts of Federalist #10. Paper Money The Abolition of Debts Redistribution of Property In a republic, a variety of institutions lay between the population and the formulation, implementation and adjudication of the law. Collectively these are supposed to limit efforts to harm the minority. On the national level this includes: A Bicameral Congress A Singular Executive An Appointed Judiciary These are established in the first three articles of the U.S. Constitution ,and they are structured in such a way to be independent of each other. This introduces a topic we will cover more thoroughly in the next section. Each institution is put in office through a separate process, which insulates them in different ways from the national electorate House – the people Senate – the states President – the electoral college Courts - appointment And each institution has a different term length, which also insulates it from the national electorate: House – 2 years Senate – 6 years President – 4 years Courts - Lifetime The longer the term, the greater the insulation. (Think about this like the length of a dog’s leash.) The Anti-Federalists wanted the shortest terms possible – yearly if possible. The fact that only one third of the Senate is up for election every two years shields that institution from ever being subject to the immediate preferences of the electorate. The fact that the federal courts serve for life, in addition to being appointed, means that they never face the electorate. The U.S. Constitution is full of factors which place distance between governing institutions and the people. Jacksonian Democracy stood opposed to this. As a consequence, the people do not rule, rather they elect representatives to rule for them and then have the periodic opportunity to replace or retain them. This raises a question about what “popular sovereignty” actually means. Are the people always sovereign, or is their sovereignty limited to the decisions they make in periodic elections? This issue was brought up before in the introductory slides. Again, while the people are indeed sovereign, the range of their power is limited. This checks the power of the majority. Think of republicanism as a check on the power of the people. Again, we explore this issue by reading through one of the more influential of the Federalist Papers Federalist #10 The Utility of the Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection - written by James Madison - wikipedia. The Text of Fed #10 Wikipedia: Fed #10 James Madison wrote Fed 10 and argued that the “well constructed union” created in the Philadelphia Convention would prevent the United States from falling prey to the excesses of democracy. Democracies, historically, have been unstable, violent, and short lived. Majorities are able to oppress minorities. Policy can shift radically based on shifts in popular sentiment. Although people must be free to participate politically, the general public must be unable to destabilize government. Majorities must be unable to undermine the rights of the minority. How can this be best done? And why does Madison care? The wealthy are a minority and in a democracy their property may be subject to redistribution and the money owed them might be subject to being forgiven. A similar sentiment would be expressed by the Danbury, Connecticut Baptist Association in 1801 in a letter to Jefferson. They were concerned that the laws of Connecticut at the time placed them, as a minority, in a position where their religious liberty would be determined by the majority. “what religious privileges we enjoy (as a minor part of the state) we enjoy as favors granted, and not as inalienable rights; and these favors we receive at the expense of such degrading acknowledgements as are inconsistent with the rights of freemen.” They wondered if Jefferson believed that their freedom to worship as they choose would be protected. Jefferson responded in his letter stating he believed that the First Amendment created a “wall of separation” between church and state. The point is that minority interests are easily disregarded and compromised by majorities. How can this be dealt with effectively? Federalist #10 argues that the republican system established in the Constitution does so. Here is a basic outline of the argument in Federalist #10. It should not substitute a full reading of the document itself. He begins with a statement of the problem: Factions have always destroyed democracies. Groups form with interest opposed to others or to the overall interests of the people. “By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” - Madison Think of factions as interest groups, what we would call today, special interests. Factions can be dealt with by focusing on causes or effects By focusing on the causes we can prevent factions from developing. By focusing on the effects we allow factions to form but ensure that they cannot do damage to the republic. There are two principle causes of factions: Freedom Diversity Freedom allows people the right to form into groups and participate politically Diversity refers to fact that people are different in their ability to process information and in the nature of their interests. But the elimination of freedom is worse than the disease. Freedom is essential. The right to form factions would later be made clear in the First Amendment. Congress shall make no law …. Abridging the right of the people to peacefully assemble and petition government for a redress of grievances. He argues that diversity is inevitable in a free society. It is impossible to make people the same if that was our goal. Why? 1 - People reason in different, often incorrect ways and develop different ideas as a result. We tend to grow attached to their ideas. 2 – Various interests evolve in a civilized society and groups evolve around those interests to protect them. It is in our nature to form into groups based on our self interest and come into conflict with others with opposing interests. Plus: It is in our nature to “vex and oppress each other” and not to cooperate for the common good. We are self-interested by nature. What’s worse, this affects people in the legislature. Legislators have their own interests and are in a position to pass legislation impacting those interests. The majority party in a legislature can do what it chooses. It can undermine the rights of the minority if it chooses. But this is inevitable in a free society. The conclusion: The causes of faction cannot be removed. Their impact can only be addressed by focusing on their effects. This is a crucial point. Human nature is written into the constitutional order. It is accepted and compensated for. We will see this again when we read through Federalist #51 and discuss ambition. So here is the question: How can factions be allowed to exist, but not allowed to undermine stability? By focusing on their effects, not causes. How can freedom not undermine stability? “To secure the public good and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our inquiries are directed.” He begins to address this question by pointing out that there are two types of factions: Minority Majority The minority faction (which is les than 50% of the population) can be checked, in a democracy, by the majority which can defeat them by vote. “If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the Constitution.” The minority can pose problems for society, but it cannot become tyrannical. Bu the majority faction can become tyrannical. It can dominate elections and use government offices to abuse minorities. “When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular Government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens.” So that’s the danger – the majority. He focuses the bulk of his attention on this. Tyranny of the Majority A democracy can become tyrannical. I have repeated this point and will continue to do so. His principle insight: In order for the majority to successfully act against the minority, it has to have: Impulse and Opportunity Impulse: A common feeling to act against an unpopular group. Opportunity: The means to act on that feeling. If they intersect – the majority can do anything. Madison argues that impulse and opportunity coincide in a direct democracy where people can meet in person, make quick decisions and implement them immediately. Think about the Salem Witch Trials or lynchings. “If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control.” Passion will translate immediately into legislation, and will be implemented immediately. This is why democracies are dangerous. They can be subject to the preferences of violent, passionate majorities. Pure democracies can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction since there is no barrier between the individual and the law. A republic – an indirect democracy - can provide the solution to this problem. A country can be both based on individual liberty and sovereignty and be resistant to tyranny of the majority and instability. There are two ways republics can cure the violence of faction. First – because representatives, not the people, will make decisions. They will less likely to be motivated by pure passion – though this is not always the case – as he admits. “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” The representative system will slow the process down so that passionate feelings will not immediately influence policy. The fact that the public can only directly impact the government in periodic elections minimizes the opportunity for passionate majorities to dominate policymaking. They can only have that influence at the appointed time. Second – because a representative government is more likely to contain multiple interests, making it less likely that a single permanent majority can be formed. The majority is likely to be split. The existence of multiple interests makes it less likely that one, or a small handful of interests will allow for the formation of a majority – especially one that can be sustained. A large country will contain many interests. The House of Representatives, for example, contains 435 members elected from 435 distinct districts around the country. The various points of view held across the country will be heard in the House. Madison argues that the smaller the republic, the more dangerous it can be because there will be a smaller number of interests contained within it. This makes the formation of a majority more likely. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.” Local governments are more likely to be tyrannical than state governments and state governments are more likely to be tyrannical than the national governments. Note: Since the Texas Constitution is far more democratic in its design and smaller in scale than the U.S., it may be more prone to tyranny of the majority. Madison’s point was that states were becoming tyrannical. The ability of the minority – land owners – to preserve their rights – property – was being jeopardized. He noted in the states at that time: “A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, [and] for an equal division of property.” A national government could suppress those tendencies. Madison's Ironic Conclusion: A Republican Solution to a Republican Problem. The answer to the problem of factions – interest groups – is to make more of them. Everyone is a minority, no one group can dominate. A minority cannot tyrannize the majority in a democracy. Certain institutions can preserve the benefits of a minority. The Senate – six year terms The Courts – appointed to the office, not subject to popular pressure Certain procedures allow a minority to stop legislation from either being passed or implemented. Filibusters Judicial Review The Anti-Federalists disagreed with Madison’s assessment and wrote a response: Anti-Federalist #10 On the preservation of parties, public liberty depends A Farmer The Antifederalist Maryland Farmer, wary of the emergence of a high-toned social class, urges ordinary Americans to "preserve your jealousy & [for] on the preservation of parties, public liberty depends. Whenever men are unanimous on great public questions, whenever there is but one party, freedom ceases and despotism commences. The object of a free and wise people should be so to balance parties, that from the weakness of all you may be governed by the moderation of the combined judgments of the whole, not tyrannized ever by the blind passions of a few individuals.“ – source. Here’s an obvious criticism of Madison’s point: What about slavery? What about the right of women? What about the rights of native tribes? Madison’s arguments seems to only apply to those who already have the right to participate. But it can also be made to apply to other groups once they attain suffrage. It may be argued that the eradication of slavery and the eventual suffrage of women was made possible by the explosion of organized groups in America. An additional contemporary criticism: Madison seems to believe that the natural development of groups will allow these groups to check each other. But is Madison painting an adequate picture of the dynamics of group formation? This raises important questions about how interests organize and become influential, and equally important questions about why others cannot. Madison seems to believe that any new interest will lead to the formation of a group around it. In some sense this is true. But not all interests in society are equally able to organize. Interests that can provide tangible material benefits to small cohesive members can organize more effectively than those that cannot. For examples: The wealthy can form more effectively than the poor. They have the resources, knowhow and connections. It is difficult to form interest groups because not everyone wants to work to make sure they are effective. Some people free ride off the work of others. If you’ve ever tried to organize a group of people you know this. We will discuss the mechanics of this more fully in the section on Interest Groups.