ASDP Japanese History and Culture (II)

advertisement

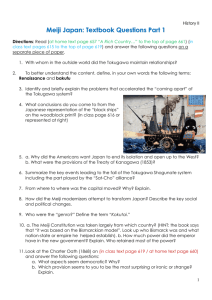

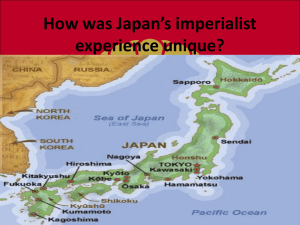

ASDP Japanese History and Culture (II) Peter Nosco - May 22, 2013 Compare these observations of Japan in the 1570s (left) and 1620 (right) • “[The people] rebel against [their rulers] whenever they have a chance, either usurping them or joining up with their enemies…. The chief root of the evil is the fact that … Japan was divided up among so many usurping barons that there are always wars among them….” Alessandro Valignano, SJ • “The government of Japan may well be accounted the greatest and most powerful Tyranny that was ever heard of in the world, for all the rest are as Slaves to the … great commander as they call him….” Richard Cocks Oda Nobunaga (1533-1582) • Succeeds remarkably in bringing about 35% of Japan (including Kyoto) under his control • Abolished toll barriers that the Ashikaga Bakufu and many daimyo and temples had established • “free markets” and “free guilds” • Removes taxes on merchants • Establishes an office for the oversight of temples and shrines • Fixes exchange rates for gold-silver-copper • Orders repairs to roads and bridges • Friendly to Christians • Betrayed by a former ally Toyotomi Hideyoshi 1536-1598 • By avenging Nobunaga’s death, Hideyoshi becomes the great rags-to-riches story. • Three extraordinary policies: – 1) 1590 Census recording population by household and after 1592 organization of the society into mutual responsibility groups – 2) 1583-1598 A complete land (cadastral) survey of each province – 1588 Sword hunt: Disarmament by confiscation, resulting in 1591 separation of warriors and farmers • And one disaster: the 1592 invasion of Korea Hideyoshi’s concern over an heir • After years of frustration, in 1593 Hideyoshi finally has a son named Toyotomi Hideyori, who in 1596 is installed as Hideyoshi’s 3-year-old successor • Increasing evidence of Hideyoshi’s mental instability • In 1598 Hideyoshi’s health begins to fail seriously and quickly deteriorates • Sets up a council of regency for Hideyori comprised of the five leading families in Japan and headed by Tokugawa Ieyasu of Mikawa • They promise their loyalty to Hideyoshi’s heir but the result is predictable once Hideyoshi dies in 1598. The Battle of Sekigahara and its aftermath • 1600 Tokugawa Ieyasu’s (1543-1616) decisive victory at Battle of Sekigahara – 1/3rd of the world’s muskets used • Political capital (Bakufu) moved to Edo (today’s Tokyo) – Grows from a sleepy fishing village to a city of a million in 100 years • 1603 Ieyasu takes and redefines the title of seii taishōgun – Title had been vacant for thirty years • 1605 Ieyasu passes title of Shogun to his son Hidetada (d. 1632) while controlling matters himself for another ten years Again, compare these observations of Japan from the 1570s and 1620 • “[The people] rebel against [their rulers] whenever they have a chance, either usurping them or joining up with their enemies…. The chief root of the evil is the fact that … Japan was divided up among so many usurping barons that there are always wars among them….” Alessandro Valignano, SJ • “The government of Japan may well be accounted the greatest and most powerful Tyranny that was ever heard of in the world, for all the rest are as Slaves to the … great commander as they call him….” Richard Cocks Sakoku (“Closing the Country”) edicts 1633-1635 • Forbid Japanese from traveling abroad • Forbid Japanese living abroad from returning to Japan • Forbid Europeans in Japan other than the Dutch on Deshima (Dejima) in Nagasaki Harbor • Decisively prohibit Christianity (with bounties for informants) and execute clergy • Remains the law of the land until the 1850s What is now there in 1640 and what is still needed for “early modernity”? • Yes - The capacity for major resource mobilization • Getting there - An urbanized and literate society with meaningful surplus wealth distributed broadly • Getting there - A developed communications and transportation infrastrure • A half-century away – a self-sustaining popular culture • 100 years away – An increasing sense of collective identity • 150 years away – a proto-scientific outlook grounded in rationalistic and humanistic perspectives. Japan’s place in the early modern world c. 1600: The Clash of Civilizations Europe China Japan Korea Religion / Philosophy LateRenaissance Christianity / Neo-Platonism Late-Ming NeoConfucianism & Buddhism Early-Tokugawa Buddhism, turning to Confucianism Mid-Choson Neo-Confucianism, shamanism Government Early modern monarchies Imperial state Shogunate (Bakufu) Kings (tribute) Power Expansionist and Expansionist but Limited imperial, Isolationist maritime land-based turning to isolationist Degree of early modernity: collective identity and resource mobilization Strong in both Strong in both Still weak in collective identity but strong in resource mobilization Weak in both The Confucian concept of four classes in Tokugawa Japan (1600-1867): • Note the great range within each class though limited mobility between classes – – – – Samurai士 Agriculturalists農 Artisans工 Merchants商 • An organic (organism-like) view of society • Outliers: Entertainers, priests, physicians, diviners, and so on • The outcastes or burakumin engaged in problematic occupations like morticians, butchers, tanners, and so on The effects of the epistemological shift from Buddhism to Neo-Confucianism • • • • • Fundamental rationalism Humanism Historical mindedness Ethnocentrism Confidence in self-cultivation and the perfectibility of people. • One effect with implications for civil society: The rise of public and private academies A revolution in Confucian thought: Ogyū Sorai 1666-1728 and the issue of nature v. invention • The Confucian Way = The Way of the Former Kings, and not the Way of Heaven • The Confucian Way 道 = comprehensive term comprised of the policies, music, rituals, laws and punishments of the past • The Confucian sages 聖人 are just men who are special because of what they invented • The Confucian Way is to be found through texts and in history, and not in nature. – It thus must be modified if it is to be applied successfully in another time and place The Genroku period and popular culture • Formally 1688-1704, but more commonly used to refer to reign of 5th Tokugawa Shogun Tokugawa Tsyunayoshi (r. 1680-1709) – Grandson of a Kyoto greengrocer – The “dog shogun” • The rise of the chōnin 町人 or urban townsman (non-samurai commoner) • Popular culture as culture that pays for itself Five requisites for a self-sustaining popular culture: 1) Urbanization Cities concentrate consumers of popular culture – 10% of Japan’s population in 1700 lived in communities with 10,000+ populations – This urban/semi-urban population grows tenfold in Japan in 100 years – 5-7% live in Japan live in 100K+ cities, compared with 2-3% in Europe – Populations of Nagoya and Kanazawa at 100K each are like Rome and Amsterdam; Osaka at 350K is like Paris; Kyoto at is 400K like London; Edo at 1M may be world’s largest city 2) Surplus wealth • Surplus wealth necessary for consumers of popular culture • Agricultural yield increases by 40% in 1600s • Benefits experienced differently by urban samurai, merchants, artisans, and even rich agriculturalists • Prominence of economic themes in the popular culture (bill paying, etc.) 3) Literacy • Woodblock printing technology reduces cost – Rejection of movable type • By end of Tokugawa period (c. 1850) male literacy of 40-50% and female literacy at 2025% (compare with England-Wales/Holland) • Question of how so many learned to read? • Consider Ihara Saikaku’s story of the pawned love letter • Print culture and creating of community 4) Communications and transportation infrastructure • Introduction of movable print technology, initially by Jesuits and also from Korea (recall invasion of 1590s) • The “Five Highways” (Gokaidō) – Post stations – Engelbert Kaempfer’s observations on Tōkaidō linking Kyoto to Edo: number of travels “scarce credible” and “on some days more crowded than the public streets” of Europe’s largest cities 5) Cultural liberality • Promotion of diversity and appreciation for the diverse possibilities of life (Charles Frankel) • Little interest in censorship except where peace/security might be threatened • Creation of licensed pleasure quarters in major metropolises – Shimabara in Kyoto and Yoshiwara in Edo Legacy of this popular culture • It was now realistically possible for someone to make a living and a reputation through various forms of cultural production. • It was essential that one neither satirize the government or challenge the status quo. • It is originally during the Genroku an urban phenomenon, but by the end of the Tokugawa all of its features will have reached through networks into semi-urban regions—part of a long process of nationalization of Japanese culture. “Dutch” (Western) Learning • Tokugawa Yoshimune’s relaxation of the ban on European books • Western Learning called Rangaku (Oranda = Holland; gaku = learning) • Two main strains: – Medicine (including botany, pharmacy, mining, chemistry and physics), – and astronomy (including calendrical science, cartography and geography) • Different reasons than why we study foreign languages and cultures today The autopsy of 1771 • Conducted by Sugita Genpaku (1713-1787) who came from a family trained for generations in Chinese medicine • With Maeno Ryōtaku, witnessed the autopsy by an eta of a 50-year old woman from Kyoto, comparing what they saw with charts in a Dutch translation of the German Anatomische tabellen by Johan Kalmus (d. 1745) • They translated Kalmus’ book into Japanese as “A New Book of Anatomy” The significance • A European book on anatomy could be more accurate than a Chinese book • Dutch learning might be in some areas superior to Japanese learning • There is the physical basis for a universal humanity • Consider the relationship between Rangaku (Western Learning) and Kokugaku (National Leaning)—1771 as a remarkable year • Effect on painting and European style realism • A new way of seeing the world Painting c. 1783 by Shiba Kōkan: “A View of Mimeguri” in Eastern Edo In nativism there is Motoori Norinaga 1730-1801 • Born and lived most of his life in Matsusaka • Family of cotton merchants • Norinaga was only interested in studies • Sent by his mother to study medicine in Kyoto 1752-57 • Returns to Matsusaka and starts a medical practice Themes in Norinaga’s thought • His work on Tale of Genji and notion of mono no aware (the pathos of things) as the essence of Japanese literature and poetry • A defense of the emotional • His sense of the wondrous qualities of life • His lifelong work on Kojiki of 712 • The 1763 “evening in Matsusaka” and his sole meeting with Kamo no Mabuchi 1771 “Rectifying Spirit” (Naobi no mitama) • The ancient Way of Japan is the Way of the kami, (kami no michi or Shinto 神道) – Neither natural nor man-made, it is a Way created by kami, not humans • Owing to the introduction of Chinese language and ways of doing things, there was a Fall from an ancient state of grace when Japanese lived in total harmony with the kami. • No separation between the past and present – Kami still control everything • Amaterasu, ancestress of the imperial family, is both the sun goddess and the sun itself • Japanese deities, and hence Japan itself is the ancestral country of the rest of the world. • The Way to cleanse oneself of the “Chinese heart” (Karagokoro) and foreign contamination is to turn to the Rectifying Deities • One can thereby reanimate one’s true “Japanese heart” and Construction of identity: Who are you? • • • • • • • Orientating oneself in time and space The creation of a heritage (patrimony) Who are we not, as much as who are we? A deep nostalgia and an idealized past A sense of a shared destination Touching the sacred in everyday life Collective identity (“we Japanese”) vs. individual identity (“I”) 1844 King William of Holland sends a letter to the shogun via Nagasaki • It warns Japan that the rest of the world is being knit together by trade • “The process is irresistible, and it draws all people together. Distance is overcome by the steamship, and any nation that holds itself aloof from this process risks the enmity of others…. When ancient laws by strict construction threaten the peace, wisdom directs that they be softened.” • The Bakufu through replies that the suggestion is impossible and asks that the King not write again • The central government simply does not know how to respond. Biddle Mission • 1846 Captain James Biddle from the U.S. arrives in Edo Bay with two ships hoping to open relations with Japan. • He was told that foreign relations could only take place in Nagasaki, and lacking authorization to use force, he withdraws. • The Bakufu again interprets this as validation of its policies • The U.S. interprets this as proof that a stronger approach is needed The Perry Mission of 1853 • Aware of the Biddle Mission’s failure, Commodore Matthew C. Perry prepares carefully, insisting that he have enough military force to guarantee his mission’s success • He arrives in Edo Bay on July 2 1853 with four “Black Ships” mounting 61 guns and carrying 967 men • His demands include protection of seamen and permission to obtain supplies and to trade, justifying these demands as the “law of nations.” • After a formal ceremony on shore, Perry departs announcing that he will return in April or May 1854— he instead returns in February. Perry and one of his “black ships” (kurobune) The 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa • 1853 Abe Masahiro, head of the Council of Elders, circulates Perry’s demands to all the Daimyō soliciting their opinions (there is no consensus) and informs the imperial court as well • It can be said that Perry thus “opens” Japanese politics as well as its ports! • Upon Perry’s return, Japan is represented in the negotiations by Hayashi, head of the Bakufu’s Shōheikō Neo-Confucian academy • Japan agrees to open two harbors at Shimoda and Hakodate where US ships could receive supplies and coal (but not actually trade) • Japan also agrees to open a consulate at Shimoda • Both sides felt that they had prevailed in the negotiations. • 1856 Townsend Harris arrives in Shimoda as the first US Consul • This first consulate is soon followed by diplomatic missions from the British and Russians • Harris meets the Shogun in 1857 and in 1858 concludes a treaty opening five ports including Edo to trade and residency for US vessels and citizens 1863-1868 Four struggles for control • 1) For control of domainal politics in Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa, i.e., the domains that will lead the coup d’etat • 2) For control over the Court and its nobles in Kyoto, as well as the person of the Emperor • 3) For control over the Bakufu’s own policies and politics • 4) (Among the foreign powers) competition for the best possible deal with Japan. The last days: Once intense rivals, Satsuma and Chōshū acting together • 1866 Satsuma and Chōshū now form an anti-Bakufu alliance – Both shogun Iemochi and emperor Kōmei die in the same year – Hitotsubashi Keiki becomes the last Tokugawa shogun, reigning less than one year, and Meiji (b. 1852) becomes emperor – Ee ja nai ka (ain’t it grand?) movement of spontaneous reverie erupts in cities – Bakufu launches reform movement with French assistance (the final Tokugawa rally) • The writing on the wall becomes clear that the Bakufu might be able to resist one or another of the domains, but that it cannot withstand the joint military opposition of both Satsuma and Chōshū • 1867 The Shogun in Kyoto resigns his office • January 1868 A “restoration” (ishin維新) of imperial rule is proclaimed by the Court, resulting in a successful coup d’etat led mostly by Satsuma and Chōshū, and with support from Mito, Tosa and Echizen – This coup and the new government have profoundly conservative leadership – The last pro-Bakufu naval units don’t surrender until Spring 1869. Immediate issues • The open ports – Extraterritoriality and loss of control of tariffs vs. – Windows of opportunity through trade and development of navy • Experiencing the West – After 1853 an explosion of interest in Western studies – The 1860 mission to the States to ratify Townsend Harris’ treaty • The strangeness of North America and Europe to even highly educated and accomplished Japanese – There were five more similar missions by the end of 1867 A study in contrasts Fukuzawa Yukichi 1835-1901 Meiji Emperor 1852-1912 Emp. Meiji 1852-1912 • Becomes emperor in February 1867 • The missing presence in the Meiji Restoration • The intense competition among the leaders of the “restoration” to control his person • Nov. 1868 moves by palanquin to Edo which is renamed Tōkyō (Eastern Capital 東京) • The open question of his own agency or power – His return visit by train to Kyoto years later Fukuzawa Yukichi 1835-1901 • Studied Dutch in Osaka • Enters Bakufu service in the new Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books • Was the interpreter for the first two Bakufu embassies to the States and Europe in 1860 and 1862 • Was principally responsible for popular knowledge in Japan of the West – Focused on explaining everyday things like hospitals, banks, political institutions, etc. – Modernization and Westernization • 1868 Founds a private academy that later becomes Keio University The Charter Oath of April 1868— The Search for Consensus “By this oath we set up as our aim the establishment of the national weal on a broad basis and the framing of a constitution and laws. • 1. Deliberative assemblies shall be widely established and all matters decided by public discussion. • 2. All classes, high and low, shall unite in vigorously carrying out the administration of affairs of state. • 3. The common people, no less than the civil and military officials, shall each be allowed to pursue his own calling so that there may be no discontent. • 4. Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of Nature. • 5. Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.” The new times • 1871 Intermarriage between commoners and samurai allowed and class distinctions eliminated – Tokugawa domains replaced by prefectures • 1872 Compulsory elementary public education begins • 1872-73 Universal male military conscription requiring four years of service – Farmers receive legal title to the land they cultivate • 1876 Samurai banned from wearing their swords • 1877 The failed Satsuma rebellion led by Saigō Takamori Changing times Early modernity • Collective identity – Literacy • • • • Resource mobilization Urbanization Subject political culture Loyalties to village and feudal lord • Centralized feudalism Modernity • Participant political culture • Widespread use of inanimate sources of energy • Technologically advanced forms of communication and transportation • National armies and navies • Public education • Independent judiciary Some additional key dates in the late-Meiji Period • 1889 • 1890 Meiji Constitution First Diet Imperial Rescript on Education • 1894-95 Victory in Sino-Japanese War • 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance • 1904-05 Victory in Russo-Japanese War • 1910 Annexation of Korea • 1912 Death of Meiji, suicide of Gen. Nogi “The Japanese Miracle” • As recently as fifty years ago, Japan was the only Asian country universally agreed to have achieved “modernity”. • The manner in which this came about was perceived by many to be a kind of miracle. • This launched a quest to duplicate the accomplishment elsewhere. • But was it a “miracle” and could it be reproduced?