Pure Leverage Increases: An Empirical Investigation

advertisement

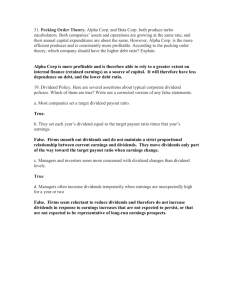

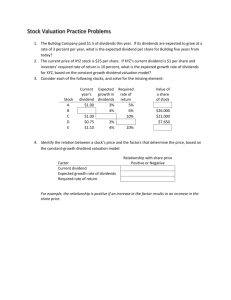

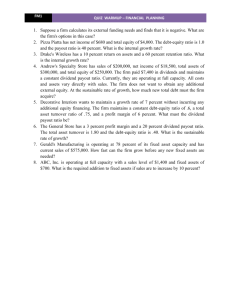

TO PAY OR NOT TO PAY: AN EXPERIENTIAL EXERCISE IN DETERMINING A FIRM’S PAYOUT POLICY Professor Robert M. Hull (Corresponding Author) rob.hull@washburn.edu (R. Hull) Professor William Roach Brenneman Professor Robert A. Weigand All of: School of Business, Washburn University; 1700 SW College Avenue, Topeka, KS 66621 Phone: + 1-670-231-1010; FAX: + 785-670-1063 Beatrice Presentation November 1, 2005 Washburn University TO PAY OR NOT TO PAY: AN EXPERIENTIAL EXERCISE IN DETERMINING A FIRM’S PAYOUT POLICY Under Review by Journal of Financial Education: Submitted 7/7/2005; Favorable Review Received 8/30/2005 Plans for Resubmission: December 2005 Published in Working Paper Series: Washburn University Working Paper Series, September 2005 To Be Presented by Professor Roach at: 2005 Decision Science Institution Conference Session IE9: Case Study and Experiential Approach Examples November 20, 2005; 8:00 a.m. − 9:30 a.m.; San Francisco, CA Overview * We develop a classroom exercise simulating the cash dividend payout decision process. The benefits to business students include (i) a thorough investigation of the complex payout issues managers must consider when determining dividend policy, and (ii) the opportunity to address the long-term trend of declining dividend payouts. * The exercise provides business instructors with several options for incorporating the dividend payout decision-making process into their classroom styles; among these are (i) experiential learning through peer group interaction and roleplaying, and (ii) the opportunity to conduct a financial analysis of a firm that has recent initiated a regular dividend payout. JEL Classification: Key Words: G35 (Payout Policy); I22 (Financial Education) Payout, Collaborative Learning Cash Dividends, Student Engagement Organization of Paper • Section I gives an introduction. • Section II provides a deeper background on the payout literature, focusing on the important relationship between dividend payout and firm value. We also discuss the decline in dividend payouts in the U.S. and frame this issue as an appropriate topic for consideration by the next generation of managers in MBA and other business school programs. • Section III present our class exercise on the payout decisionmaking process. The appendices supply resources on the dividend payout exercise including the actual tasks and supplementary materials with questions and solutions. • Section IV provides concluding comments. Major Purpose Our major purpose is to offer a learning exercise to address two timely issues. * The first issue concerns the firm’s choice of dividend payout (cash dividends ÷ operating earnings). Bernstein (2005) argues that the low dividend payout makes no sense. * The second issue concerns student engagement through active and collaborative learning. Burbridge (2005) argues that students need to become more involved in active and collaborative learning. Addressing the Two Issues • • • To address the above two issues, we design a class exercise on dividend payout policy to engage students in a manner where learning the “stuff of management” can take place by studying the current controversial topic of low dividend payouts. Our payout exercise challenges students to participate in the collaborative and cooperative aspects of team learning (D. Johnson and R. Johnson, 1975; Keaton, 1976; Bouton and Garth, 1983; Michaelsen, 1994; McKeachie, 1994) through an experiential simulation of the payout decision-making process where students will have an opportunity to debate the many relevant factors used when making dividend policy choices. By involvement in the payout decision-making process through roleplaying (as a member of a consulting team or of a Board of Directors), students can begin to experience how the payout choice is made in practice. This will lead to an increased appreciation of the complex factors faced by managers who are responsible for determining their firm's dividend policy. TEACHING OUTCOMES Teaching Outcomes Include: (1) Students will delve deeper into payout policy by examining research issues. (2) Students will use newer valuation metrics and traditional methods of financial analysis in conjunction with real firm data to make decisions about a firm’s payout policy. (3) Students will (within a team setting) become familiar with the decision-making process as practiced by Board of Directors. (4) Students will interact and share knowledge with other students in a class exercise that challenges them to verbally express their views. Literature Review Two Lines of Early Thought Two distinctly different branches of thought emanate from the early literature on corporate payout policy and its primary historical manifestation, cash dividends. • The first line of thought emerges from the classic works of Williams (1938), Gordon (1959), and Lintner (1956), asserting that dividends are an important determinant of firm value and a first-order concern for value-maximizing managers. • The second perspective, attributable to Miller and Modigliani (1961) and echoed in Black (1976), suggests cash dividends are irrelevant for firm value, a trivial detail to be dealt with only after the firm's investment policy is established. FIRST VIEW Dividends Are Directly Related to Intrinsic Value The value of a firm and its securities as the present value of a stream of dividends and/or particular definitions of free cash flow. Corporate surveys Lintner (1956), Fama and Babiak (1968), Baker, Farrelly, and Edelman (1985), and Baker, Veit, and Powell (2001) suggest managers believe dividends should be related to permanent (rather than temporary) increases in profits, consistent with the idea that dividends are fundamentally related to firm value. Graham and Dodd (1962) urge analysts to value firms based on demonstrated earnings power (like dividends), rather than speculative notions of future earnings. First View associated with Dividend Valuation Model P0 = D1 / (R-G) where P0 is the price per Share D1 is the perpetual dividend cash flow per share beginning at t = 0 R is the required rate of return G is the growth rate in dividends POR = D1 / EPS1 is the payout ratio 1-POR = proportion of earnings retained See http://www.fool.com/news/commentary/2004/commentary04100402.htm for an example of how an analyst used DVM to make money on stock picks First View seen in fact Analysts Use the Dividend Valuation Model even Today • The view that dividends are related to firm value is firmly rooted in the conventional wisdom of the early 20th century. This view is reflected in classic texts and research papers, valuation models still used by analysts today, and the magnitude of dividend payout investors were accustomed to receiving. • Merrill Lynch uses the model as a component of its marketbeating Alpha Surprise Model. • JP Morgan uses the model as an important input into the valuation and stock selection process. Figure One Years Dividend Yield Capital Total Gains Returns 1802-1870 6.4% 0.7% 7.1% 1871-1925 5.2% 2.2% 7.4% 1926-2001 4.1% 6.2% 10.3% 1982-2001 2.9% 11.6% 14.5% Second View Dividends Are Not Directly Related to Firm Value • Miller and Modigliani (M&M 1961) disagree with the idea that dividends directly affect firm value. Posing the following question early in their paper: "Do companies with generous distribution policies consistently sell at a premium above those with niggardly payouts?” is an obvious reference to the wisdom that firms should pay out healthy dividends. • M&M present a model that shows the value of a company is determined by the firm's assets and the cash flows generated by those assets, not how the cash flows are distributed to shareholders. • M&M contend that different payout policies constitute nothing more than slicing a fixed pie of cash flows into different pieces, and that in perfect, frictionless markets the value of these pieces will always sum up to the value generated by the underlying investment policy that produced the cash flows. Changing the form of the distribution does not affect value. Second View Expanded so that Dividends Can Cause Loss of Value, Signal Information, Reduce Agency Costs, or Reduce Risk • • • • • Black (1976) takes M&M's ideas even further and asserts that when taxes are considered, paying dividends actually destroys value. Black (1976) coins an enduring phrase when he declares the convention of dividends to be a "puzzle," and leaves the reader to wonder why the corporate world has not adopted his vision of zero (or near zero) dividend payouts. One of the first attempts to explain why firms would want to pay dividends suggests corporate dividend policy reflects managers' expectations of future firm earnings, a specific application of an economic concept known as signaling, pioneered by Ackerloff (1970) and Spence (1973). This idea is incorporated into the finance literature on dividends and information by Bhattacharya (1979), Miller and Rock (1985), and John and Williams (1985). In these and other studies managers are portrayed as intentionally communicating their expectations of future firm earnings via dividend increases and decreases. As seen later can also affect agency costs and risk. Recent Attack On Second View • DeAngelo and DeAngelo (2005) present a voluminous and convincing critique of M&M's analysis, demonstrating that the finding of dividend irrelevance obtains because M&M's framework mandates 100% payouts — the effect of "niggardly" payouts cannot be considered in their model. The irrelevance result is therefore hardwired into their assumptions, which means their argument is little more than an elegant tautology. • DeAngelo and DeAngelo assert that M&M and Black have “ . . . limited our vision about the importance of payout policy and sent researchers off searching for frictions that would make payout policy matter, while it has mattered all along . . . ” Empirical Evidence • • • • • Some studies find a positive relation between dividend changes and future earnings (Watts, 1973; Gonedes,1978; Nissim and Ziv, 2001). Others disagree (Benartzi, Michaely and Thaler, 1997; Dyl and Weigand, 1998; Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan, 2002). Studies of dividend initiation report some evidence of short-term earnings growth following first-time dividend payments (Healy and Palepu, 1988; Benartzi, Michaely and Thaler, 1997). Researchers argue that dividends provide investors with a way to monitor agent-manager behavior (Easterbrook, 1984; Jensen,1986). Researchers offer mixed evidence as to whether dividends reduce agency costs (Lang and Litzenberger, 1989; Borokhovich, Brunarski, Harman and Kehr, 2005). Researchers have proposed that dividend payments are associated with lower firm risk (Venkatesh, 1989; Dyl and Weigand,1998; Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan, 2002). Dividends and Payout Policy in the 21st Century • • • • • The benefits of dividends make it difficult to justify the low market demand for dividends and firms' propensity not to pay. The average dividend yield on U.S. stocks from 1982-2001 was a paltry 2.9%. The precipitous decline in dividends is underscored by the fact that yields averaged 3.9% from 1982-1991, but only 2.0% from 1992-2001. Fama and French (2001) confirm that the convention of cash dividend payments has been in a long-term downtrend. While 67% of publicly-traded firms in the U.S. paid dividends in 1978, only 21% of firms were dividend payers in 1999. Fama and French find markets have become increasingly tilted toward firms that are less likely to pay dividends — small firms with low profitability and high growth opportunities. They also report all types of firms have become less likely to pay dividends, however, including larger firms with slower growth opportunities. Julio and Ikenberry (2004) present evidence of a mild revival in the tendency to pay dividends. They attribute renewed interest in dividends to firms needing to reassure investors about the quality of their earnings in a post-Enron/Global Crossing/Tyco world. Another reason firms may be more willing to pay dividends is that tax rates in the U.S. on dividend income and capital gains are now equal (15%). Julio and Ikenberry also suggest technology firms (like Microsoft) that went public in the 1980s and 1990s are now maturing and facing slower growth opportunities. Recent Thinking & Findings: Repurchases for Dividends • • Recent survey evidence by Brav, Graham, Harvey and Michaely (2005) indicates that share repurchase is now more highly-favored than dividends, although respondents believe both forms of payout communicate important information to markets (85% for repurchases and 80% for dividends). Thirty-six percent of managers believe repurchases are as important as they were 15-20 years ago (implying the relative importance of repurchases has increased) while only 40% believe dividends are as important (implying the relative important of dividends has decreased). Julio and Ikenberry (2004) show that, despite the substitution of share repurchase for dividends, total payouts to shareholders as a percentage of earnings have remained stable from 1984-2004. These authors also point out that while both dividends and share repurchase signal managers' optimism about the permanence and expected stability of earnings, repurchases offer the additional benefit of explicitly communicating managers' belief that their shares are undervalued. However; share repurchase indicates short-term optimism while dividends represent a more reliable, long-term commitment to pay out excess capital. Our Exercise Will Challenge Students to Work with Financial Statements • Students will work with newer financial metrics • Students will work with traditional financial ratio analysis methods • Students will apply trend analysis • Students will look at industry norms FINANCIAL RATIO ANALYSIS • Financial ratio analysis consists of various methodologies. In our paper, we discuss (1) relatively more recent valuation methods as represented by economic value added (EVA®), return on invested capital and free cash flow and (2) long-standing traditional methods as epitomized by the DuPont Model. • Blumenthal (1998) and Firer (1999) indicates that traditional approaches typified by the DuPont Model will continue to dominate financial analysis for some time including the newer metrics like EVA. • Financial ratios must be interpreted properly and cautiously because of inherent accounting-based limitations and unethical manipulation. Class Exercise: “To Pay or Not to Pay” • Our dividend exercise can be tailored to fit into the typical class time slots of either 50 minutes or 75 minutes. • We have found that it works nicely with class sizes of 15 to 25 students. For larger class sizes, the exercise can be repeated twice or the three teams (described below) can choose to designate the students who will represent their team in the actual exercise. Class Exercise: “To Pay or Not to Pay” Three Teams and Three Tasks • • • • • • • In our exercise, students are assigned to one of three teams. One team defends the "pro-dividend" side of the issue (see Appendix 1 for their task). A second team advocates the "con-dividend" viewpoint (see Appendix 2 for their task). Members assigned to the first two tasks are consultants. Consultants are assumed to have academic and/or practical experience in terms of financial management decision-making. The third and final team makes up the Board of Directors (see Appendix 3 for their task). Students forming the Board of Directors will render a final decision as to whether there will be a change in the firm's dividend policy. To challenge the competitive spirit of those arguing the “pro” and “con” sides, we instruct Board members to consider the quality of the arguments presented by the "pro" and "con" sides when making their decision. Class Exercise: “To Pay or Not to Pay” • By working in teams where students are assigned specific roles, we utilize an experiential method that stresses cooperative and collaborative learning through peer group interaction and role-playing (Coleman, 1948; Collier, 1983; Meyers and Jones, 1993; Michaelsen, Watson and Black, 1989; McKeachie, 1994). • To achieve outcomes related to the exercise’s goal of student engagement, we encourage adherence to the practices, principles, and techniques related to group activities (Bouton and Gartch, 1983; Fiechtner and Davis, 1985; Abelson and Babcock, 1986; Katzenback and Smith, 1993; Robbins and Finley, 1995). • Katzenback and Smith suggest that instructors adhere to the following: ● requires all members to contribute equivalent amounts of real work so that a sense of mutual accountability is achieved; ● exploit the power of positive feedback, recognition, and reward; ● keep teams small enough so the students can communicate openly with others and understand their roles and skills. • In regards to the last suggestion, we have found the team sizes of about six work the best. Class Exercise: “To Pay or Not to Pay” Two Possible Applications • The case discussion can be applied one of two ways. Instructors who prefer a shorter and more direct method can focus on the material in Appendices 1–3. • Instructors who prefer that students conduct a financial analysis of a specific firm can also apply the materials in Appendices 4–8, which provides financial data for Microsoft Corporation for several years preceding and following their dividend initiation. Shortened Form of Exercise • Using the shortened form of our exercise (which includes only the first three appendices) has yielded satisfactory results and positive feedback over the years. • This form provides some advantages including the fact the exercise can be accomplished in a shorter period of time for instructors constrained by time. • With the firm’s product assumed as unique for the shortened form, there is no inherent advantage given to either team through looking at industry norms that could dictate what payout might be optimal. • While lack of such particulars has some advantages, it does not provide students with an opportunity to study an actual firm with real data. More Rigorous Exercise • For instructors who want a more rigorous exercise, we supply real data in the lengthened form of our exercise by looking at a firm that has recently instituted paying dividend (Microsoft Corporation). • This lengthened form adapts the materials given in Appendices 1– 3 with the supplementary materials supplied in Appendices 4–8. As seen in these latter five appendices, students can pursue a variety of possible activities. • These five appendices contain a sample of assignments and solutions that include recent valuation metrics and a flow chart of an expanded DuPont analysis. • As seen in the flow chart, ROE (and thus earnings available for cash dividend distribution) has been influenced negatively over time by margin management through increased costs. Class Exercise: “To Pay or Not to Pay” Prior to actually participating in our class exercise on dividend policy decision-making, we suggest that instructors do the following: • have students study assigned textbook readings and any supplied materials accompanying lecture materials; • hand out the assigned task given in the first three appendices while providing needed instructions (see ground rules next overhead); • arrange team meetings using class time if necessary (and encouraging chat room meetings if applicable); • present the supplementary materials if a more rigorous application is desired (e.g., offer additional resources in Appendices 4–8 to help instructors further frame the controversial payout issues students will debate when participating in the exercise). Suggested Ground Rules • First, we encourage teams to delegate tasks to individuals with tasks based on points of interest identified in the team meeting. • Second, Board members are seated in the middle and are flanked on the two sides by the “pro” and “con” team participants. • Third, we allow one five minute “time-out” per team with the instructor moderating the time-outs. • Fourth, formal rules of a debate are not required. • Fifth, when the debate is over, the Chair asks members of the “pro” and “con” sides to leave the classroom. • Sixth, we require each participant to turn in a one page summary of the salient points describing their fundamental role in the exercise. After presenting the general instructions including these ground rules, we meet separately with each team to answer individual questions about the assigned task and give further team-specific counsel. These separate meetings can take place during class time with the instructor visiting each team as they meet privately to go over their task and make individual assignments. The instructor can also arrange to meet outside class time with teams or representatives of teams. Student Research Possibilities • • • • • Instructors can require advanced students (taking upper level finance or MBA courses) to perform research supplementing textbook and lecture materials on the payout debate. Appendices 4–8 can be used for this research purposes. Additionally, scholarly journal articles can be assigned by those instructors who want to challenge more sophisticated students. Finance journals are rich in articles related to the theoretical arguments and empirical evidence about payout issues with textbooks having their own list of references on dividend policy. To further enhance student preparation for participation in the exercise, instructors can encourage the use of spreadsheet and/or program versions of the various payout models. Concerning the Internet, there are web pages that can be used as part of the student preparation for the exercise. Internet Sites for Analysts’ Assessment Internet sites provide details to find analysts’ assessment and which can be used in conjunction with financial ratio analysis to make predictions about investment possibilities. Sites include: • http://finance.yahoo.com • http://www.hoovers.com/free • http://moneycentral.msn.com/home.asp Assessing Student Satisfaction • • • • To assess student satisfaction (especially when first conducting the exercise), we suggest that formal student feedback be gathered so that the exercise can be enriched and tailored to meet the needs of a particular type of student. To help improve the peer learning process, students should be asked to comment on other team members. We think information on the following attributes (on a scale of one to five) can be important in any evaluative instrument an instructor might choose to use: attendance and participation at team meetings; completion of delegated team tasks; respect for others’ opinions; level of interest and commitment; and, level of contribution in terms of competencies and creativity. Alternately, students can also be asked to anonymously assess their peers by simply stating who participated effectively and who did not participate effectively. Student can also be required to evaluate their own performance as effective or ineffective. Finally, students can be asked to write a paragraph or two on what they have learned as team members, and to specify what problems they have encountered in participating as a team member. Task 1: Increasing Payout • • • • INSTRUCTIONS: There are three “tasks”: Task One, Task Two, and Task Three. You have been assigned Task One . . . Details concerning your task are given below. You are a consultant for Taskpro, Inc., which is a company that provides specialists to help firms make financial management decisions. Taskpro has just been hired by Divitable, Inc. to help Divitable determine if it should increase its payout. As an expert in the area of dividend policy, you will be on the team of consultants formed by Taskpro to advise Divitable about its payout policy. You are aware that another firm, Taskcon, Inc., has also been hired by Divitable to argue against Divitable increasing its payout . . . . . . It is expected that you will give management a series of arguments for why increasing its cash dividend payout is the correct path to follow . . . . . . When you appear before the Board, you are to have a one page summary of your arguments and findings that support an increase in dividends. To supplement your one page summary, you are allowed to bring other notes with you to the Board meeting . . . Task 2: Decreasing Payout INSTRUCTIONS: There are three “tasks”: Task One, Task Two, and Task Three. You have been assigned Task Two . . . Details of your task are given below. You are employed as a consultant for Taskcon, Inc., which is a company that provides consultants to advise firms on financial management decision-making. Taskcon has recently been hired by Divitable Inc., to supply arguments against increasing Divitable’s dividend payout. Because of your past experience in dividend policy, you have been assigned to the team that will advise Divitable against the pitfalls of paying out too much dividends. Although you are not privy to inside information on Divitable, you do know that it produces a unique array of products making it hard to identify its specific industry or any major competitors. You also know that the Conaby family controls 20 percent of the voting shares of Divitable, which is a large-sized company by NASDAQ standards having $20 billion in total assets . . . Task 3: Board of Directors INSTRUCTIONS: There are three “tasks”: Task One, Task Two, and Task Three. You have been assigned Task Three . . .Your task and instructions are described below. You are a member of the Board of Directors of Divitable, Inc., which is listed on NASDAQ . . . At the Board meeting, you will sit in judgment as each consulting team presents its arguments. It will be your task to decide which team of specialists presents the best arguments as this can highly influence your decision . . . Board members are expected to hold their own private gettogether, prior to the official Board meeting, to formulate a strategy for the meeting . . . After the consultants have presented their arguments, they will be asked to leave the meeting. At that time, you and other Board members will render your decision about whether your company’s payout will be increased. Your decision and explanation will be made known to consultants. Task Extension (For Rigorous Application) • INSTRUCTIONS: . . . you have been given additional information, where Divitable is benchmarking its own dividend decision to that of Microsoft Corporation. This information involves the following empirical extensions to the case. As before, you are to discuss your task only with designated classmates who have been assigned the same task as yourself. Details of your extended task are given below. • Perform a financial analysis of Microsoft for the years leading up to and following the announcement that Microsoft would begin paying regular cash dividends (Microsoft announced its initial dividend on January 16, 2003). Microsoft's financial statements from 2001-2004 are included on the following pages . . .Your task is to critique the financial performance of Microsoft and use your findings to support the argument for or against a dividend payout increase by Divitable, Inc. (depending upon whether you are an employee of Taskpro or Taskcon). Your financial analysis should include the following . . . Question 1 / Solution 1 • Question 1. Report trends in Microsoft's basic financial ratios and comment on the company's financial health in the following categories: – Liquidity: current and quick ratios – Asset Management: days sales outstanding, fixed assets turnover and total assets turnover – Debt Management: debt ratio, times interest earned – Profitability: return on assets and a DuPont analysis of return on equity (profit margin, total asset turnover and equity multiplier)* • Solution 1. See Appendix 7 for numbers on Microsoft from 2001−2004. Appendix 7 Microsoft Financial Ratio Trend Analysis 2001 2002 2003 2004 3.56 3.81 4.22 4.71 Quick Asset Management Ratios 3.56 3.76 4.17 4.69 Fixed Assets Turnover Days Sales Outstanding 11.0 12.5 14.4 15.8 55.0 11.0 0.43 66.0 12.5 0.42 58.9 14.4 0.39 58.4 15.8 0.40 Liquidity Ratios Current Fixed Assets Turnover Total Assets Turnover Appendix 7 Microsoft Financial Ratio Trend Analysis 2001 2002 2003 2004 Debt / Equity Ratio 0.25 0.30 0.26 0.23 Debt / Total Assets Ratio 0.20 0.23 0.21 0.19 Debt Management Times Interest Earned No interest expenses reported. Profitability Profit Margin Total Assets Turnover Return on Assets Equity Multiplier Return on Equity 29.0% 27.6% 23.4% 22.2% 0.43 0.42 0.39 0.40 12.4% 11.6% 9.2% 8.8% 1.26 1.23 1.25 1.30 15.5% 15.0% 11.6% 10.9% Question 2 / Solution 2 • Question 2. Discuss Microsoft's ability to build value for its shareholders as evidenced by trends in the following valuation metrics: – NOPAT (net operating profit after tax) – ROIC (return on invested capital) – EVA© (economic value added)** – FCF (free cash flow) • Solution 2. Appendix 7 has numbers for Microsoft Corporation from 2001−2004. Trend Analysis for Recent Valuation Metrics including EVA Appendix 7 supplies trend analysis for recent valuation metrics. Below we define the relevant variables used in the metrics deployed. • NOWC (Net Operating Working Capital) is Cash & Equivalents + Accounts Receivables + Inventories – Accounts Payables – Accrued Expenses. • OLTA (Operating Long Term Assets) is Net Property, Plant & Equipment. • TOC (Total Operating Capital or Invested Capital) is NOWC + OLTA. • NOPAT (Net Operating Profit after Tax) is Operating Income (or EBIT) times (1−T) where T is the corporate tax rate estimated as Income Taxes divided by Pre-Tax Income. • ROIC (Return on Invested Capital) is NOPAT divided by the prior year’s TOC. • EVA (Economic Value Added) is NOPAT minus the quantity consisting of the WACC times the prior year’s TOC. • FCF (Free Cash Flow) is NOPAT minus the quantity consisting of this year’s TOC minus the prior year’s TOC. Appendix 7 Microsoft (MSFT) Valuation Metrics Trend Analysis (in billions of dollars where applicable) 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Net Operating Working Capital $6,456 $5,663 $6,465 $9,285 $19,237 Operating Long Term Assets $1,903 $2,309 $2,268 $2,223 $2,326 Total Operating Capital $8,359 $7,972 $8,733 $11,508 $21,563 Cash Dividend Cash Dividend Payout $0 $0 $0 $857 $1,729 0 0 0 0.11 0.21 Appendix 7 Microsoft (MSFT) Valuation Metrics Trend Analysis (in billions of dollars where applicable) 2001 2002 2003 2004 NOPAT (net operating profit after tax) $7,721 $7,829 $7,531 $8,168 ROIC (return on invested capital) 92.4% 98.2% 86.2% 71.0% EVA (economic value added) $6,885 $7,032 $6,658 $7,017 FCF (free cash flow) $8,108 $7,068 $4,756 -$1,887 Weighted Average Cost of Capital 10.0% 10.0% 10.0% 10.0% A Description of the DuPont Model • Below we define the key DuPont ratios in Appendix 8 where we show their influence on ROE. • Margin Management (Data from Income Statement): Net Profit Margin (NPM) = Net Income / Sales = NI / S (1) • Asset Management (Data from Balance Sheet): Asset Turnover (AT) = Sales / Total Assets = S / TA (2) • Debt Management (Data from Balance Sheet): Financial Leverage (FL) = Total Assets / Stockholders’ Equity = TA / E (3) where Financial Leverage can also be referred to as the Equity Multiplier (EM). • When we multiply out the above three equations, we have: ROE = NPM * AT * FL = (NI / S)*(S/TA)*(TA/E). Canceling out from the denominators and numerators for “S” and “TA”, we get: ROE = NPM / E. (4) Appendix 8: DuPont Analysis of Microsoft Corporation Expanded DuPont Analysis for Microsoft (MSFT) from 2001 to 2004 (in billions of dollars) Sales Comparison Key: 36.8 2004 2001 25.3 Gross Profit minus 33.3 Net Profit 8.17 Net Profit Margin 22.2% 29.0% Financial Leverage Return on Equity 10.9% Return on Assets 1.23 = 15.5% 1.25 X 8.84% 0 12.4% net profit sales 21.3 minus 7.72 divided by Other Costs total assets equity net profit total assets 13.9 Sales 12 36.8 10. 25.3 95 Cash Sales 61 74.8 divided by 47.3 Total Assets Inventory 70.6 0.66 plus 92.4 59.3 0.75 plus Current Assets 0.40 sales total assets 32 25.3 Asset Turnover 39.7 Earnings Per Share (diluted basis) 3.46 multiplied by 0.43 Shareholders' Equity 6.72 25.1 36.8 net profit equity Cost of Goods Sold Fixed Assets 21.8 19.6 CONCLUSION: ROE has only been slightly influenced (in a negative manner) by debt management (financial leverage decreased slightly) and asset management (asset turnover has also decreased only slightly). However, ROE has been significantly influenced (in a negative manner) by margin management where net profit margin has fallen 23 percent. This fall stems from the 83 percent increase in costs compared to only a 45 percent increase in sales. While there appears to be greater net profits to pay greater dividends, the overall return is down. 0.4 0.0 mm plus Accounts Receivable 5.9 3.7 plus Other Current Assets 3.7 4.4 .0.03 Question 3 / Solution 3 Question 3. Compare Microsoft's stock returns over the period 2001-2004 with the returns to the S&P 500 and NASDAQ indices. Solution 3. MSFT's historical stock prices can be downloaded directly into a spreadsheet from Yahoo!Finance: http://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=MSFT S&P 500 at: http://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=%5EGSPC NASDAQ at: http://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=%5EIXIC • Reading List for Researching Dividend Policy Ackerloff, G., (1970). The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, 488-500 Bajaj, M. and A. Vijh, (1990). Dividend Clienteles and the Information Content of Dividend Changes Journal of Financial Economics 26, 193-219 Baker, H., G. Farrelly, and R. Edelman, (1985). A Survey of Management Views on Dividend Policy Financial Management 14, 78-84 Baker, H., E. Veit, and G. Powell, (2001). Factors Influencing Dividend Policy Decisions of NASDAQ Firms. The Financial Review 38, 19-38 Bhattacharya, S., (1979). Imperfect Information, Dividend Policy, and 'The Bird in the Hand Fallacy'. Bell Journal of Economics 10, 259-270 Benartzi, S., R. Michaely, and R. Thaler, (1997). Do Changes in Dividends Signal the Future or the Past? Journal of Finance 52, 1007-1034 Bernstein, P., (2005). Dividends and the Frozen Orange Juice Syndrome. Financial Analysts Journal 61, 25-30 Black, F., (1976). The Dividend Puzzle. Journal of Portfolio Management 10, 7-9. Boehme, R. and S. Sorescu, (2002). The Long-Run Performance Following Dividend Initiations and Resumptions: Underreaction or Product of Chance? Journal Finance 57, 871-900 Borokhovich, K, K. Brunarski, Y. Harman, and J. Kehr, (2005). Dividends, Corporate Monitors and Agency Costs. The Financial Review 40, 37-65 Brav, A., J. Graham, C. Harvey, and R. Michaely, (2005). Payout Policy in the 21st Century. Journal of Financial Economics 77, 483-527 DeAngelo, H. and L. DeAngelo, (2005). The Irrelevance of the MM Dividend Irrelevance Theorem, Working Paper, University of Southern California Denis D. J., D. Denis, and A. Sarin, (1994). The Information Content of Dividend Changes: Cash Flow Signaling, Overinvestment and Dividend Clienteles. Journa of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 29, 567-587 Dyl, E. and R. Weigand, (1998). The Information Content of Dividend Initiations: Additional Evidence. Financial Management 27, 27-35 Easterbrook, F., (1984). Two Agency-Cost Explanations of Dividends. American Economic Review 74, 650-659 Fama, E. and H. Babiak, (1968). Dividend Policy: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 63, 1132-1161. Fama, E. and K. French, (2001). Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower Propensity to Pay? Journal of Financial Economics 60, 3-43 Gonedes, N, (1978). Corporate Signaling, External Accounting, and Capital Market Equilibrium: Evidence on Dividends, Income, and Extraordinary Items. Journa of Accounting Research 16, 26-79 Gordon, M. (1959). Earnings and Stock Prices. Review of Economics and Statistics 41, 99-105 Graham, B., D. Dodd, and C. Tatham (1951). Security Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill (NOT IN) Grullon, G., R. Michaely, and B. Swaminathan, (2002). Are Dividend Changes a Sign of Firm Maturity? Journal of Business 75, 387-424 Healy, P. and K. Palepu, (1988). Earnings Information Conveyed by Dividend Initiations and Omissions. Journal of Financial Economics 22, 149-175 Jensen, M., (1986). Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers. American Economic Review 76, 323-329 John, K. and J. Williams, (1985). Dividends, Dilution, and Taxes: A Signaling Equilibrium. Journal of Finance 40, 1053-1070. Julio, B. and D. Ikenberry, (2004). Reappearing Dividends. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 16, 89-100. Koch, A. and Amy Sun, (2004). Dividend Changes and the Persistence of Past Earnings Changes. Journal of Finance 59, 2093-2116. Lang, L. and R. Litzenberger, (1989). Dividend Announcements: Cash Flow Signaling vs. Free Cash Flow Hypothesis. Journal of Financial Economics 24, 181-19 Lintner, J., (1956). Distribution of Income of Corporations Among Dividends, Retained Earnings and Taxes. American Economic Review 46, 97-113. Miller, M. and F. Modigliani, (1961). Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares. Journal of Business 34, 411-433. Miller, M., (1987). The Information Content of Dividends. In Macroeconomics: Essays in Honor of Franco Modigliani (MIT press: Cambridge, Mass.), edited by J. Bossons, R. Dornbusch, and S. Fischer, 37-61 Miller, M. and K. Rock, (1985). Dividend Policy Under Asymmetric Information. Journal of Finance 40, 1031-1052 Nissim, D., and A. Ziv, (2001). Dividend Changes and Future Profitability. Journal of Finance 56, 2111-2133 Pettit, R., (1972). Dividend Announcements, Security Performance, and Capital Market Efficiency. Journal of Finance 27, 993-1008. Siegel, J., (2002a). Stocks for the Long Run, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. Siegel, J., (2002b). The Dividend Deficit, The Wall Street Journal, February 13 2002, p. A20. Spence, M., (1973). Job Market Signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics 87, 296-332. Concluding Statements This paper has presented a class exercise to teach payout policy. The class exercise is designed so that instructors can enhance experiential learning. The exercise addresses two timely issues. The first issue concerns why do not firms pay more dividends. Bernstein (2005) concludes that the “. . . demand for dividends is approximately nil. This phenomenon makes little sense.” The second issue concerns student engagement through active and collaborative learning. An engaged student is one who combines knowledge with the ability to apply this knowledge within an organizational and team setting so that the “stuff of management” (e.g., the actual, unquantifiable decision-making processes) can be better experienced.