fossil record - LSU Geology & Geophysics

advertisement

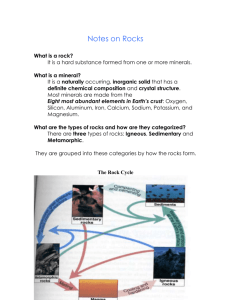

Chapter 5 Rocks, Fossils and Time— Making Sense of the Geologic Record Geologic Record • The fact that Earth has changed through time – is apparent from evidence in the geologic record • The geologic record is the record – of events preserved in rocks • Although all rocks are useful – in deciphering the geologic record, – sedimentary rocks are especially useful • The geologic record is complex – and requires interpretation, which we will try to do • Uniformitarianism is useful for this activity Geologic Record • for nearly 14 million years of Earth history – preserved at Sheep Rock – in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon • Fossils in these rocks – provide a record – of climate change – and biological events Stratigraphy • Stratigraphy deals with the study – of any layered (stratified) rock, – but primarily with sedimentary rocks and their • • • • composition origin age relationships geographic extent • Sedimentary rocks are almost all stratified • Many igneous rocks – such as a succession of lava flows or ash beds – are stratified and obey the principles of stratigraphy • Many metamorphic rocks are stratified Stratified Igneous Rocks • Stratification in a succession of lava flows in Oregon. Stratified Sedimentary Rocks • Stratification in sedimentary rocks consisting of alternating layers of sandstone and shale, in California. Stratified Metamorphic Rocks • Stratification in Siamo Slate, in Michigan Vertical Stratigraphic Relationships • Surfaces known as bedding planes – separate individual strata from one another – or the strata grade vertically – from one rock type to another • Rocks above and below a bedding plane differ – in composition, texture, color – or a combination of these features • The bedding plane signifies – a rapid change in sedimentation – or perhaps a period of nondeposition Superposition • Nicolas Steno realized that he could determine – the relative ages of horizontal (undeformed) strata – by their position in a sequence • In deformed strata, the task is more difficult – but some sedimentary structures • such as cross-bedding – and some fossils – allow geologists to resolve these kinds of problems • we will discuss the use of sedimentary structures • more fully later in the term Principle of Inclusions • According to the principle of inclusions, – – – – which also helps to determine relative ages, inclusions or fragments in a rock are older than the rock itself • Light-colored granite – in northern Wisconsin – showing basalt inclusions (dark) • Which rock is older? – Basalt, because the granite includes it Age of Lava Flows, Sills • Determining the relative ages – of lava flows, sills and associated sedimentary rocks – uses alteration by heat – and inclusions • How can you determine – whether a layer of basalt within a sequence – of sedimentary rocks – is a buried lava flow or a sill? – A lava flow forms in sequence with the sedimentary layers. • Rocks below the lava will have signs of heating but not the rocks above. • The rocks above may have lava inclusions. Sill – A sill will heat the rocks above and below. – The sill might also have inclusions of the rocks above and below, – but neither of these rocks will have inclusions of the sill. Unconformities • So far we have discussed vertical relationships – among conformable strata, • which are sequences of rocks • in which deposition was more or less continuous • Unconformities in sequences of strata – represent times of nondeposition and/or erosion – that encompass long periods of geologic time, – perhaps millions or tens of millions of years • The rock record is incomplete. – The interval of time not represented by strata is a hiatus. The origin of an unconformity • In the process of forming an unconformity, – deposition began 12 million years ago (MYA), – continuing until 4 MYA – For 1 million years erosion occurred – removing 2 MY of rocks – and giving rise to – a 3 million year hiatus • The last column – is the actual stratigraphic record – with an unconformity Types of Unconformities • Three types of surfaces can be unconformities: – A disconformity is a surface • separating younger from older rocks, • both of which are parallel to one another – A nonconformity is an erosional surface • cut into metamorphic or intrusive rocks • and covered by sedimentary rocks – An angular unconformity is an erosional surface • on tilted or folded strata • over which younger rocks were deposited Types of Unconformities • Unconformities of regional extent – may change from one type to another • They may not represent the same amount – of geologic time everywhere A Disconformity • A disconformity between sedimentary rocks – in California, with conglomerate deposited upon – an erosion surface in the underlying rocks An Angular Unconformity • An angular unconformity in Colorado – between steeply dipping Pennsylvanian rocks – and overlying Cenozoic-aged conglomerate A Nonconformity • A nonconformity in South Dakota separating – Precambrian metamorphic rocks from – the overlying Cambrian-aged Deadwood Formation Lateral Relationships • In 1669, Nicolas Steno proposed – – – – his principle of lateral continuity, meaning that layers of sediment extend outward in all directions until they terminate Terminations may be abrupt • at the edge of a depositional basin • where eroded • where truncated by faults Gradual Terminations – or they may be gradual • where a rock unit • becomes progressively thinner • until it pinches out • • • • or where it splits into thinner units each of which pinches out, called intertonging • • • • where a rock unit changes by lateral gradation as its composition and/or texture becomes increasingly different Sedimentary Facies • Both intertonging and lateral gradation – indicate simultaneous deposition – in adjacent environments • A sedimentary facies is a body of sediment – – – – – with distinctive physical, chemical and biological attributes deposited side-by-side with other sediments in different environments Sedimentary Facies • On a continental shelf, sand may accumulate – in the high-energy nearshore environment – while mud and carbonate deposition takes place – at the same time – in offshore low-energy environments Marine Transgressions • A marine transgression – occurs when sea level rises – with respect to the land • During a marine transgression, – – – – the shoreline migrates landward the environments paralleling the shoreline migrate landward as the sea progressively covers more and more of a continent Marine Transgressions • Each laterally adjacent depositional environment – produces a sedimentary facies • During a transgression, – – – – the facies forming offshore become superposed upon facies deposited in nearshore environments Marine Transgression • The rocks of each facies become younger – in a landward direction during a marine transgression • One body of rock with the same attributes – (a facies) was deposited gradually at different times – in different places so it is time transgressive younger – meaning the ages vary from place to place shale older shale A Marine Transgression in the Grand Canyon • Three formations deposited – in a widespread marine transgression – exposed in the walls of the Grand Canyon, Arizona Marine Regression • During a marine regression, – sea level falls – with respect – to the continent – and the environments paralleling the shoreline – migrate seaward Marine Regression • A marine regression – is the opposite of a marine transgression • It yields a vertical sequence – – – – with nearshore facies overlying offshore facies and rock units become younger in the seaward direction younger shale older shale Walther’s Law • Johannes Walther (1860-1937) noticed that – the same facies he found laterally – were also present in a vertical sequence, – now called Walther’s Law – which holds that • the facies seen in a conformable vertical sequence • will also replace one another laterally – Walther’s law applies • to marine transgressions and regressions Extent and Rates of Transgressions and Regressions • Since the Late Precambrian, – 6 major marine transgressions followed – by regressions have occurred in North America • These produce rock sequences, – bounded by unconformities, – that provide the structure – for U.S. Paleozoic and Mesozoic geologic history • Shoreline movements – are a few centimeters per year • Transgression or regressions – with small reversals produce intertonging Causes of Transgressions and Regressions • Uplift of continents causes regression • Subsidence causes transgression • Widespread glaciation causes regression – due to the amount of water frozen in glaciers • Rapid seafloor spreading, – expands the mid-ocean ridge system, – displacing seawater onto the continents • Diminishing seafloor-spreading rates – increases the volume of the ocean basins – and causes regression Relative Ages between Separate Areas • Using relative dating techniques, – – – – it is easy to determine the relative ages of rocks in Column A and of rocks in Column B • However, one needs more information – to determine the ages of rocks – in one section relative to – those in the other Relative Ages between Separate Areas • Rocks in A may be – younger than those in B, – the same age as in B – older than in B • Fossils could solve this problem Fossils • Fossils are the remains or traces of prehistoric organisms • They are most common in sedimentary rocks – and in some accumulations – of pyroclastic materials, especially ash • They are extremely useful for determining relative ages of strata – but geologists also use them to ascertain – environments of deposition • Fossils provide some of the evidence for organic evolution – and many fossils are of organisms now extinct How do Fossils Form? • Remains of organisms are called body fossils. – and consist mostly of durable skeletal elements – such as bones, teeth and shells – rarely we might find entire animals preserved by freezing or mummification Body Fossil • Skeleton of a 2.3-m-long marine reptile – in the museum at Glacier Garden in Lucerne, Switzerland Body Fossils • Shells of Mesozoic invertebrate animals – known as ammonoids and nautiloids – on a rock slab • in the Cornstock Rock Shop in Virginia City Nevada Trace Fossils • Indications of organic activity – including tracks, trails, burrows, and nests – are called trace fossils • A coprolite is a type of trace fossil – consisting of fossilized feces – which may provide information about the size – and diet of the animal that produced it Trace Fossils • Paleontologists think – that a land-dwelling beaver – called Paleocastor – made this spiral burrow in Nebraska Trace Fossils • Fossilized feces (coprolite) – of a carnivorous mammal • Specimen measures about 5 cm long – and contains small fragments of bones Body Fossil Formation • The most favorable conditions for preservation – of body fossils occurs when the organism – possesses a durable skeleton of some kind – and lives in an area where burial is likely • Body fossils may be preserved as – unaltered remains, • meaning they retain • their original composition and structure, • by freezing, mummification, in amber, in tar – or altered remains, • with some change in composition or structure • permineralized, recrystallized, replaced, carbonized Unaltered Remains • Insects in amber • Preservation in tar Unaltered Remains • 40,000year-old frozen baby mammoth • found in Siberia in 1971 • It is 1.15 m long and 1.0 m tall • and it had a hairy coat • Hair around the feet is still visible Altered Remains • Petrified tree stump – in Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado • Volcanic mudflows – 3 to 6 m deep – covered the lower parts – of many trees at this site Altered Remains • Carbon film of a palm frond • Carbon film of an insect Molds and Casts • Molds form – when buried remains leave a cavity • Casts form – if material fills in the cavity Mold and Cast Step a: burial of a shell Step b: dissolution leaving a cavity, a mold Step c: the mold is filled by sediment forming a cast Cast of a Turtle • Fossil turtle – showing some of the original shell material • body fossil – and a cast Fossil Record • The fossil record is the record of ancient life – preserved as fossils in rocks • Just as the geologic record – must be analyzed and interpreted, – so too must the fossil record • The fossil record – is a repository of prehistoric organisms – that provides our only knowledge – of such extinct animals as trilobites and dinosaurs Fossil Record • The fossil record is very incomplete because – – – – – bacterial decay, physical processes, scavenging, and metamorphism destroy organic remains • In spite of this, fossils are quite common Fossils and Telling Time • William Smith • 1769-1839, an English civil engineer – independently discovered – Steno’s principle of superposition • He also realized – that fossils in the rocks followed the same principle • He discovered that sequences of fossils, – especially groups of fossils – are consistent from area to area • Thereby discovering a method – of relatively dating sedimentary rocks at different locations Fossils from Different Areas • To compare the ages of rocks from two different localities • Smith used fossils Principle of Fossil Succession • Using superposition, Smith was able to predict – the order in which fossils – would appear in rocks – not previously visited • Alexander Brongniart in France – also recognized this relationship • Their observations – lead to the principle of fossil succession Principle of Fossil Succession • Principle of fossil succession – holds that fossil assemblages (groups of fossils) – succeed one another through time – in a regular and determinable order • Why not simply match up similar rocks types? – Because the same kind of rock – has formed repeatedly through time • Fossils also formed through time, – but because different organisms – existed at different times, – fossil assemblages are unique Distinct Aspect • An assemblage of fossils – has a distinctive aspect – compared with younger – or older fossil assemblages Matching Rocks Using Fossils • Geologists use the principle of fossil succession – to match ages of distant rock sequences – Dashed lines indicate rocks with similar fossils – thus having the same age Matching Rocks Using Fossils youngest oldest • The youngest rocks are in column B – whereas the oldest ones are in column C Relative Geologic Time Scale • Investigations of rocks by naturalists between 1830 and 1842 – based on superposition and fossil succession – resulted in the recognition of rock bodies called systems – and the construction of a composite geologic column – that is the basis for the relative geologic time scale Geologic Column and the Relative Geologic Time Scale Absolute ages (the numbers) were added much later. Example of the Development of Systems • Cambrian System – – – – Sedgwick studied rocks in northern Wales and described the Cambrian System without paying much attention to the fossils His system could not be recognized beyond the area • Silurian System – Murchinson described the Silurian System in South Wales – including carefully described fossils – His system could be identified elsewhere Dispute of Systems • Ordovician System – Lapworth assigned the overlap – between the two to a new system, – the Ordovician System Dispute • The dispute was settled in 1879 – when Lapworth proposed the Ordovician Stratigraphic Terminology • Because sedimentary rock units – are time transgressive, – they may belong to one system in one area – and to another system elsewhere • At some localities a rock unit – straddles the boundary between systems • We need terminology that deals with both – rocks—defined by their content • lithostratigraphic unit – rock content • biostratigraphic unit – fossil content – and time—expressing or related to geologic time • time-stratigraphic unit – rocks of a certain age • time units – referring to time not rocks Lithostratigraphic Units • Lithostratigraphic units are based on rock type – with no consideration of time of origin • The basic lithostratigraphic element is a formation – which is a mappable rock unit – with distinctive upper and lower boundaries • It may consist of a single rock type • such as the Redwall limestone – or a variety of rock types • such as the Morrison Formation • Formations may be subdivided – into members and beds – or collected into groups and supergroups Lithostratigraphic Units • Lithostratigraphic units in Zion National Park, Utah • For example: The Chinle Formation is divided into – Springdale Sandstone Member – Petrified Forest Member – Shinarump Conglomerate Member Biostratigraphic Units • A body of strata recognized – only on the basis – of its fossil content – is a biostratigraphic unit • the boundaries of which do not necessarily • correspond to those of lithostratigraphic units • The fundamental biostratigraphic unit – is the biozone Time-Stratigraphic Units • Time-stratigraphic units • also called chronostratigraphic units – consist of rocks deposited – during a particular interval – of geologic time • The basic time-stratigraphic unit – is the system Time Units • Time units simply designate – certain parts of geologic time • Period is the most commonly used time designation • Two or more periods may be designated as an era • Two or more eras constitute and eon • Periods can be made up of shorter time units – epochs, which can be subdivided into ages • The time-stratigraphic unit, system, – corresponds to the time unit, period Classification of Stratigraphic Units Lithostratigraphic Units • Supergroup – Group • Formation – Member » Bed TimeTimestratigraphic Units Units • Eonothem • Eon – Erathem • System – Series » Stage – Era • Period – Epoch » Age Correlation • Correlation is the process – of matching up rocks in different areas • There are two types of correlation: – Lithostratigraphic correlation • simply matches up the same rock units • over a larger area with no regard for time – Time-stratigraphic correlation • demonstrates time-equivalence of events Lithostratigraphic Correlation • Correlation of lithostratigraphic units such as formations – traces rocks laterally across gaps Lithostratigraphic Correlation • We can correlate rock units based on – composition – position in a sequence – and the presence of distinctive key beds Time Equivalence • Because most rock units of regional extent – are time transgressive – we cannot rely on lithostratigraphic correlation – to demonstrate time equivalence • Example: – sandstone in Arizona is correctly correlated – with similar rocks in Colorado and South Dakota – but the age of these rocks varies from • Early Cambrian in the west • to middle Cambrian farther east Time Equivalence • The most effective way – to demonstrate time equivalence – is time-stratigraphic correlation – using biozones • But other methods are useful Biozones • For all organisms now extinct, – their existence marks two points in time • their time of origin • their time of extinction • One type of biozone, the range zone, – is defined by the geologic range • total time of existence – of a particular fossil group • a species, or a group of related species called a genus • Most useful are fossils that are – easily identified, geographically widespread – and had a rather short geologic range Guide Fossils • The brachiopod Lingula – – – – is not useful because, although it is easily identified and has a wide geographic extent, it has too large a geologic range • The brachiopod Atrypa – – – – and trilobite Paradoxides are well suited for time-stratigraphic correlation, because of their short ranges • They are guide fossils Concurrent Range Zones • A concurrent range zone is established – by plotting the overlapping ranges – of two or more fossils – with different geologic ranges • This is probably the most accurate method – of determining time equivalence Short Duration Physical Events • Some physical events – of short duration are also used – to demonstrate time equivalence: – distinctive lava flow • would have formed over a short period of time – ash falls • take place in a matter of hours or days • may cover large areas • are not restricted to a specific environment • Absolute ages may be obtained for igneous events – using radiometric dating Absolute Dates and the Relative Geologic Time Scale • Ordovician rocks – are younger than those of the Cambrian – and older than Silurian rocks • But how old are they? – When did the Ordovician begin and end? • Since radiometric dating techniques – work on igneous and some metamorphic rocks, – but not generally on sedimentary rocks, – this is not so easy to determine Absolute Dates for Sedimentary Rocks Are Indirect • Mostly, absolute ages for sedimentary rocks – must be determined indirectly by – dating associated igneous and metamorphic rocks • According to the principle of cross-cutting relationships, – – – – – a dike must be younger than the rock it cuts, so an absolute age for a dike gives a minimum age for the host rock and a maximum age for any rocks deposited across the dike after it was eroded Indirect Dating • Absolute ages of sedimentary rocks – are most often found – by determining radiometric ages – of associated igneous or metamorphic rocks Indirect Dating • The absolute dates obtained – from regionally metamorphosed rocks – give a maximum age – for overlying sedimentary rocks • Lava flows and ash falls interbedded – with sedimentary rocks – are the most useful for determining absolute ages • Both provide time-equivalent surfaces – giving a maximum age for any rocks above – and a minimum age for any rocks below Indirect Dating • Combining thousands of absolute ages – associated with sedimentary rocks – of known relative age – gives the numbers – on the geologic time scale Summary • The first step in deciphering the geologic history of a region – is determining relative ages of the rocks • First ascertain the vertical relationships – among the rock layers – even if they have been complexly deformed • The geologic record – is an accurate chronicle of ancient events, – but it has many discontinuities or unconformities – representing times of nondeposition, erosion or both Summary • Simultaneous deposition – – – – in adjacent but different environments yields sedimentary facies, which are bodies of sediment or sedimentary rock with distinctive lithologic and biologic attributes • According to Walther’s law, – the facies in a conformable vertical sequence – replace one another laterally • During a marine transgression, – a vertical sequence of facies results – with offshore facies superposed over nearshore facies Summary • During a marine regression, – – – – a vertical sequence of facies results with nearshore facies superposed over offshore facies, the opposite of transgression • Marine transgressions and regressions result from: – uplift and subsidence of continents – the amount of water in glaciers – rate of seafloor spreading (volume of ridges) Summary • Most fossils are found in sedimentary rocks – although they might also be in volcanic ash, – volcanic mudflows, but rarely in other rocks • Fossils are actually quite common, – – – – but the fossil record is strongly biased toward those organisms that have durable skeletons and that lived where burial was likely • Law of fossil succession (William Smith) – holds that fossil assemblages succeed one another – through time in a predictable order Summary • Superposition and fossil succession – were used to piece together – a composite geologic column – which serves as a relative time scale • To bring order to stratigraphic terminology, – geologists recognize units based entirely on content • lithostratigraphic and biostratigraphic units – and those related to time • time-stratigraphic and time units • Lithostratigraphic correlation involves – demonstrating the original continuity – of a presently discontinuous rock unit over an area Summary • Biostratigraphic correlation of range zones, – – – – and especially concurrent range zones, demonstrates that rocks in different areas are of the same relative age, even with different compositions • The best way to determine absolute ages – of sedimentary rocks and their contained fossils – is to obtain absolute ages – for associated igneous and metamorphic rocks