4. Pest Management Plan - Documents & Reports

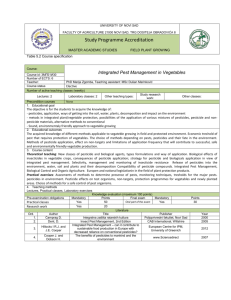

advertisement