Better Assignments, Better Writing!

advertisement

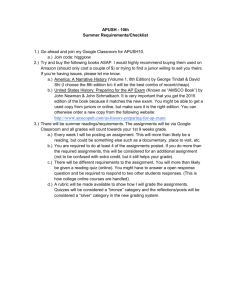

Better Assignments, Better Writing! Shawnee PorterCare Room, The Ortner Center Union College 1 December 2009 What Constitutes “Writing”? That depends on the discipline. “Writing” may take the form of any or all of these: journal entries field notes lab reports response papers term or research papers case studies narratives book, film, or television reviews annotated bibliographies a photograph, painting, or graphic a piece of music Poorly-Written Assignments Use intimidating diction Encourage fragmentary responses, idle speculation, or frivolity Are vague or assume students have more knowledge than they do Pose numerous questions that provoke incoherence Ask for personal information Pit novice writers against professionals Do not stipulate audience or purpose and, therefore, context Poorly-Written Assignments Have contradictory or conflicting audiences Emphasize mechanics and format over content Embed presuppositions Ask too much or do not indicate an acceptable level of generality What could we add to this list? It’s Not Me, It’s Them I don’t do any of those things! So why do my students still turn in weak writing? The “easy-way-out-for-me” answers: Students procrastinate. They don’t draft. They write in a vacuum. They lack sufficient preparation—e.g., haven’t done the readings leading up to the written work. They have little or no foundation (translation: it’s the elementary and academy teachers’ fault). They are not “college material.” It’s Not Them, It’s Me Is it possible that we don’t always understand how to create assignments? Is it possible that we ourselves rush through creating an assignment, don’t write multiple drafts, never or rarely seek feedback from our colleagues, aren’t really clear about what we want, don’t try the assignment ourselves, expect students to just “figure it out”? Defining the Disconnect Professors’ Expectations vs. Students’ Understandings Professors’ Goals vs. Students’ Translation into Processes Professors’ Hopes vs. Students’ Strategies Defining the (Re)Connect Make clear how the assignment relates to the course’s stated goals because students are too often used to writing for a grade rather than writing to learn. Share ideas or examples of how you yourself (or former students) would approach the assignment because students often need models with which to compare and/or contrast their own ideas. Defining the (Re)Connect Especially for discipline-specific writing, explain how the student’s writing may compare to writing in the field because students need to practice modeling the work of professionals. In addition to a well-written assignment, make clear from the beginning how you will evaluate the writing—e.g., provide a rubric—because students find comfort in these boundaries. Well-Written Assignments Are tied to specific course goals Appear in print Clearly state purpose Detail process/method/manageable steps Define audience Call for a specific genre or disciplinespecific tone and style Delineate level of (in)formality Require a specific documentation style Explain the criteria for evaluation Include due dates Are aesthetically pleasing on the page Resources Colleagues in and across disciplines The Studio for Writing and Speaking Studio consultants Students in your class Bean, John C. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. Indianapolis: Wiley, 1996. Print. The WAC Clearinghouse found at <http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop2i.cfm>.