NDCA---Round 1 - NDCA Policy 2013-2014

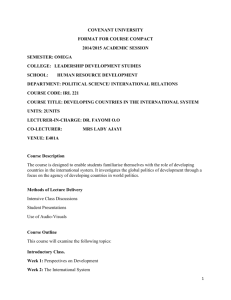

advertisement