Tax-benefit linkages

advertisement

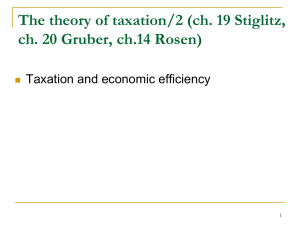

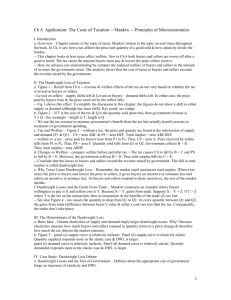

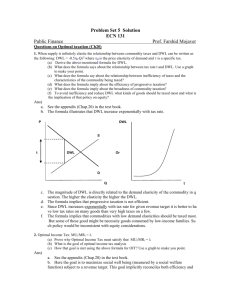

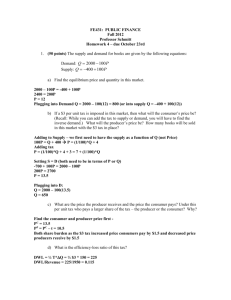

Chapter 20 Tax Inefficiencies and Their Implications for Optimal Taxation Social efficiency is maximized at the competitive equilibrium (in the absence of market failures). Taxes entail a deviation from competitive, frictionless markets. Consequently, taxing market participants creates deadweight loss. So, we will look at Taxation and economic efficiency Optimal commodity taxes Optimal income taxes, and Tax-benefit linkages in financing social insurance programs. Figure 1 Imposing a Tax on Producers Price per gallon (P) S2 S1 The tax creates deadweight loss.B P2 = $1.80 DWL P1 = $1.50 A $0.50 The tax on gasoline shifts the supply curve. C D1 Q2 = 90 Q1 = 100 Quantity in billions of gallons (Q) DWL When Supply is Infinitely Elastic DWL=.5*b*h d .5*t*dx p dx (dp) x dx x dp p d q=p+t DWL p 0 0.5(t ) d (dp) x x so DWL 0.5(t ) 2 d p p x0 So in this simple example, DWL is proportional to the square of the tax rate and the demand elasticity. Taxation and economic efficiency Elasticities determine tax inefficiency The efficiency consequences are identical, regardless of which side of the market the tax is imposed on. Just as price elasticities of supply and demand determine the distribution of the tax burden, they also determine the inefficiency of taxation. As shown in the following figure, higher elasticities imply bigger changes in quantities, and larger deadweight loss. Figure 2 Deadweight Loss Increases with Elasticities Demand is fairly inelastic, and DWL is small. (a) Inelastic Demand P P S2 (b) Elastic demand Demand is more elastic, and DWL is larger. S1 S2 S1 B P2 B DWL P1 P2 P1 A 50¢ Tax C DWL A 50¢ Tax C D1 D1 Q2 Q1 Q Q2 Q1 Q Taxation and economic efficiency Determinants of deadweight loss This formula for deadweight loss: S D 2 Q DWL 2(S D ) P 1 2 Q When S , DWL D 2 P Deadweight loss rises with the elasticity of demand. The appropriate elasticity is the Hicksian compensated elasticity, not the Marshallian uncompensated elasticity. Deadweight loss also rises with the square of the tax rate. That is, larger taxes have much more DWL than smaller ones. The “marginal” DWL increases as taxes increase. Figure 3 S3 P D P3 B P2 P1 S2 S1 The next $0.10 tax creates a larger marginal DWL, TheBCDE. first $0.10 tax creates little DWL, ABC. A C $0.10 E $0.10 D1 Q3 Q2 Q1 Q Taxation and economic efficiency Deadweight loss and the design of efficient tax systems The more one loads taxes onto one source (and consequently, the higher the rate), the faster DWL rises. Efficient tax systems spread the burden broadly. Thus, efficient tax systems have a broad base and low rates. The fact that DWL rises with the square of the tax rate also implies that government should not raise and lower taxes, but rather set a long-run tax rate that will meet its budget needs on average. For example, to finance a war, it is more efficient to raise the rate by a small amount for many years, rather than a large amount for one year (and run deficits in the short-run). This notion can be thought of as “tax smoothing,” similar to the notion of individual consumption smoothing. Optimal commodity taxation Ramsey rule Optimal commodity taxation is choosing tax rates across goods to minimize the deadweight loss for a given government revenue requirement. MDWLi The Ramsey Rule is: MRi D It sets taxes across commodities so that the ratio of the marginal deadweight loss to marginal revenue raised is equal across commodities. The goal of the Ramsey Rule is to minimize deadweight loss of a tax system while raising a fixed amount of revenue. 8 measures the value of having another dollar in the government’s hands relative to the next best use in the private sector. Smaller values of 8 mean additional government revenues have little value relative to the value in the private market. Optimal commodity taxation Inverse elasticity rule The inverse elasticity rule, based on the Ramsey result, allows us to relate tax policy to the elasticity of demand. The government should set taxes on each commodity inversely to the demand elasticity. Therefore, ignoring equity, less elastic items should be taxed at a higher rate. Two factors must be balanced when setting optimal (efficient) commodity tax rates (again, ignoring equity): The elasticity rule: Tax commodities with low elasticities. The broad base rule: It is better to tax many goods at lower rates, because deadweight loss increases with the square of the tax rate. Thus, the government should tax all of the commodities that it is able to, but at different rates. OPTIMAL INCOME TAXES Optimal income taxation is choosing the tax rates across income groups to maximize social welfare subject to a government revenue requirement. Raising tax rates will likely affect the size of the tax base. Thus, increasing the tax rate on labor income has two effects: Tax revenues rise for a given level of labor income. Workers reduce their earnings, shrinking the tax base. At high tax rates, this second effect becomes important. Thus, there are equity-efficiency tradeoffs in designing income tax rates. The Laffer curve motivated the supply-side economic policies of the Reagan presidency Figure 7 The Laffer curve demonstrates that at some point, tax revenue falls. Tax revenues right side 0 wrong side τ*% 100% Tax rate Optimal income taxes General model with behavioral effects The goal of optimal income tax analysis is to identify a tax schedule that maximizes social welfare, while recognizing that raising taxes has conflicting effects on revenue. The optimal tax system meet the condition that tax rates are set across groups such that: MU i MRi Where MUi is the marginal utility of individual i, and MR is the marginal revenue from that individual. As with optimal commodity taxation, this outcome represents a compromise between two considerations: Vertical equity Behavior responses Figure 8 MU/MR Mrs. Poor Mr. Rich Optimal income taxation equates the ratio of (MU/MR) across individuals. MU MU λ MR poor MR rich 10% 20% Tax rate Low income may have higher MUc. A given tax will raise more for a high income household (up to a point), so MR is higher. TAX-BENEFITS LINKAGES AND THE FINANCING OF SOCIAL INSURANCE PROGRAMS Tax-benefit linkages are direct ties between taxes paid and benefits received. Summers (1989) shows that such linkages can affect the equity and efficiency of a tax. The link between payroll taxes and social insurance benefits can lead the incidence to fall more fully on workers than might be presumed. The key point of Summers’ analysis is that with taxes alone, only the labor demand curve shifts, but with tax-benefit linkages, the labor supply curve shifts as well. That is, workers are willing to work the same amount of hours at a lower wage, because they get some other benefit as well, such as workers’ compensation or health insurance. Figure 10 Tax-Benefit Linkages Wage (W) Wage (W) C Creating smaller DWL. S1 S1 Mandated benefits A shift also the supply curve. E W1 W1 A F W W B 2 B S2 2 W D1 D 3 D1 D2 L2 L1 D2 Labor (L) L2 L3 L1 Labor (L) Wages adjust by more with the tax-benefit linkage, employment falls by less, and deadweight loss is smaller than with a pure tax. Tax-benefits linkages and the financing of social insurance programs: The model With full valuation, the cost of the program is fully shifted onto workers in the form of lower wages, and there is no deadweight loss or employment reduction. This raises some issues with tax-benefit linkages, especially with respect to employer mandates. If there is no inefficiency, why doesn’t the employer simply provide the benefit without government intervention? Market failures, such as adverse selection, may be present. The employer that provides a benefit such as workers’ compensation or health insurance may end up with high risks. When are there tax-benefit linkages? They are strongest when the taxes paid are linked directly to a specific benefit that workers can receive.