101.Ch 8. Mankiw

advertisement

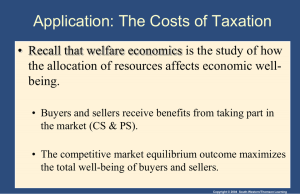

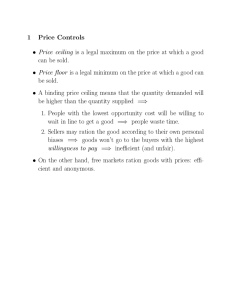

Ch 8. Application: The Costs of Taxation -- Mankiw -- Principles of Microeconomics I. Introduction a. Overview – Chapter returns to the topic of taxes. Mankiw returns to the topic several times throughout the book. In Ch. 6 saw how a tax affects the price and quantity of a good sold & how elasticity divide the burden. -- This chapter looks at how taxes affect welfare. Saw in Ch 6 both buyers and sellers are worse off after a good is taxed. The tax raises the amount buyers must pay & lowers the price sellers receive. -- Here we advance our understanding by compare the reduced welfare of buyers and sellers to the amount of revenue the government raises. The analysis shows that the cost of taxes to buyers and sellers exceeds the revenue raised by the government. II. The Deadweight Loss of Taxation a. Figure 1 – Recall from Ch 6 -- revenue & welfare effects of the tax do not vary based on whether the tax is levied on buyers or sellers. --Levied on sellers – supply shifts left & Levied on buyers – demand shifts left. In either case, the price paid by buyers rises & the price received by the sellers falls. -- Fig 1 shows this effect. To simplify the discussion in this chapter, the figures do not show a shift in either supply or demand (although one must shift). Key result: tax wedge b. Figure 2 – If T is the size of the tax & Q is the quantity sold (post tax), then government revenue is T x Q. See rectangle – height is T, length is Q. -- We use the tax revenue to measure government’s benefit from the tax but actually benefit accrues to recipients of government spending. c. Tax and Welfare – Figure 3 – without a tax, the price and quanity are found at the intersection of supply and demand (P1 & Q1) – CS = area ABC & PS = area DEF. Total surplus = area ABCDEF -- welfare w/ a tax – price paid by buyers rises from P1 to PB. Thus, CS = area A. Price received by sellers falls from P1 to PS. Thus, PS = area F. Quantity sold falls from Q1 to Q2. Government collects B + D. Thus, total surplus = area ABDF. d. Changes in Welfare – compare welfare before and after tax – The tax causes CS to fall by B + C and PS to fall by D + E. However, the government collects B + D. Thus total surplus falls by C + E. -- Conclude that the losses to buyers and sellers exceed the revenue raised by government. This fall in total surplus is called deadweight loss. e. Why Taxes Cause Deadweight Loss – Remember, the market equil maximizes total surplus. When a tax raises the price to buyers and lowers the price to sellers, it gives buyers an incentive to consume less and sellers an incentive to produce less. As buyers and sellers respond to these incentives, the size of the market shrinks. f. Deadweight Losses and the Gains From Trade – Mankiw constructs an example where buyers willingness to pay is X and sellers cost is Y. Because X > Y, gains from trade. Suppose X – Y = Z. If T > Z where T is the tax on the transaction, then no transaction & the benefits of the trade (Z) are lost. -- See also Figure 4 – tax causes the quantity to drop from Q1 to Q2. At every quantity between Q1 and Q2, the gains from trade (difference between buyer’s value & seller’s cost) are less than the tax. Consequently, the trades don’t take place. III. The Determinants of the Deadweight Loss a. Basic Idea – Greater elasticities of supply and demand imply larger deadweight losses. Why? Because elasticities measure how much buyers and sellers respond in quantity terms to a price change & therefore how much the tax distorts the market outcome. b. Figure 5 – panel (a) supply curve is relatively inelastic. Panel (b) supply curve is relatively elastic. Quantity supplied responds more in the elastic case & DWL is larger. panel (c) demand curve is relatively inelastic. Panel (d) demand curve is relatively elastic. Quantity demanded responds more in the elastic case & DWL is larger. IV. Case Study: Deadweight Loss Debate a. Deadweight Losses and the Size of Government – Debates about the appropriate size of government hinge on measures of elasticity and DWL 1 -- The larger the DWL, the higher the cost of government – high DWL – stronger case for small government & low DWL – weaker case for small government. b. Measuring DWL of Taxation – disagreement among economists. Why? Taxes on labor (FICA tax and income tax) are the primary source of government revenue and DWL of these taxes is hard to measure. -- Why? A labor tax places a wedge between what firms pay for labor and what workers receive. If we add all forms of labor taxes together, the marginal tax rate (tax on last dollar of earnings) is almost 50% for most workers. -- Economists disagree about whether this 50% labor tax rate has a large or small DWL b/c they disagree about the elasticity of labor supply. c. Labor Supply Elasticities – 1. those who argue that labor taxes do not distort outcomes much believe that labor supply is relatively inelastic. Most people, they argue, would work full time regardless of the take home wage 2. Those who argue that labor taxes cause large distortions believe labor supply is more elastic. Some groups may have inelastic supply but most don’t. Why? -- many workers can adjust the number of hours they work (e.g. overtime). -- some families have second earners (often married women w/ children) w/ some discretion over whether to enter the labor market. -- many elderly can choose when to retire & once retired the wage determines whether they work part time. -- some people engage in illegal economic activity or simply evade taxes by accepting “under the table” payments. V. Deadweight Loss and Tax Revenue as Taxes Vary a. Motivation – Taxes are frequently changed – some tax increases may reduce revenue. b. Figure 6 – shows the effect of small medium and large taxes holding constant the market’s supply and demand curves. As the size of the tax rises in panels (a), (b), & (c), the DWL grows larger & larger. -- In fact, the DWL of a tax rises even more rapidly than the size of the tax. Why? DWL is an area of a triangle and the area of a triangle depends on the square of its size. If we double the size of a tax, for instance, the base and the height of the triangle double, so the DWL rises by a factor of 4. c. Revenue – the government’s tax revenue is the size of the tax times the amount of the good sold. As the size of the tax increases from panel (a) to (b), revenue grows. However, revenue falls as the size of the tax increases from panel (b) to (c). Why? Linear demand curves become most elastic at the highest prices. Thus, in percentage terms, Q falls significantly at higher prices and tax revenue drops. -- For a very large tax, no revenue would be raised b/c people would stop buying the good altogether. d. Figure 6 – panels (d) and (e) summarize these results. VI. Case Study: The Laffer Curve and Supply-Side Economics a. Basic Argument – Laffer argues that tax cuts can raise revenues. His basic argument is much like panel (e) from Figure 6. In essence, Laffer argued that the US was on the downward sloping portion of the curve. b. Counterarguments – the idea that a cut in tax rates could raise revenue was correct from a theoretical standpoint – but many doubted whether this would occur in practice. Reagan’s tax cuts passed in the early 1980s were associated with rising rather than falling deficits. c. Political Implications – While empirical economic foundation was weak, the idea was an easy political sale. At the time, the US suffered from budget deficits but everyone loves lower taxes. Idea suggested that we could cut taxes and deficits would not increase – they would decrease. -- Because the cut in taxes was designed to increase labor supply – referred to as supply-side economics. d. Intermediate Position – while an overall cut in tax rates normally reduces tax revenue, some taxpayers at some times may be on the other side of the Laffer curve. -- Other things equal, a tax cut is more likely to raise revenue if the cut applies to those taxpayers facing the highest rates (i.e., the rich). -- Also, the rich have greater ability to rearrange work effort and income. More likely to have second earners, discretionary decisions about starting new businesses, etc. -- In countries w/ higher tax rates, more likely that tax cuts increase tax revenues. Studies of Sweden where average taxpayers faced marginal tax rates of 80% suggested that a cut would raise revenues. e. Basis for Disagreenment – once again, elasticity of labor supply. 2