Pablo Picasso jeudi 21 février 2008 23:06 First Communion Is the

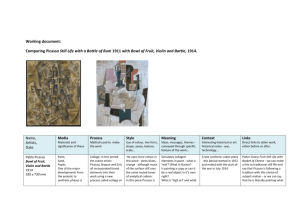

advertisement