Rose-Paper - European Association of Tax Law Professors

advertisement

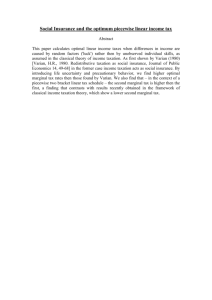

1 2003 EATLP Congress in Cologne The Notion of Income from Capital The Notion of Income from an Economic Point of View by Manfred Rose, University of Heidelberg Table of Contents Summary ............................................................................................................... 2 1. Factors determining the definition of taxable income from an economic standpoint ...................................................................................................... 2 2. The economic notion of lifetime income as a guideline for the notion of taxable income ............................................................................................... 9 2.1 The citizen’s lifetime income from an economic standpoint ................ 9 2.2 The notion of taxable income corresponding to the notion of lifetime income .................................................................................................. 10 3. Evaluation of alternative systems of taxing lifetime income ....................... 15 3.1 Decision neutrality ............................................................................... 15 3.2 Administrative efficiency .................................................................... 16 3.3 Taxation versus tax burdens ................................................................ 17 4. The simplest method of taxing lifetime income ........................................... 18 References ........................................................................................................... 21 2 Summary A notion of taxable income that is sound from an economic standpoint must take into account both the purposes and the effects of the income tax. The income tax should serve primarily to raise public revenues and to siphon off purchasing power from the citizens. In addition, the income tax should be as neutral as possible in its impact on decision-making. It is possible to structure the income tax in such a way that it distorts neither citizens’ decisions on whether to spend their income today or tomorrow, nor the investment decisions of companies. When structuring the income-tax base it is not possible to take into consideration the fact that the income tax, as indeed any other tax, discriminates willingness to work against the choice of leisure. An income tax can be considered to be fair if it guarantees the same tax burden for the same economic ability-to-pay together with protection of the subsistence level of consumption throughout a citizen’s life (humane concept of ability-to-pay). The traditional concept of income taxation embraces all inflows of funds from market activities during the tax period regardless of their sources. Such non-historical inclusion of taxable items which flow in from extremely different sources results in massive discrimination of both savers and investors. The effective tax burden is several times the legally established tax rate and the longer saving and investment are continued, the higher the tax burden rises. The burden, moreover, is unfairly distributed: where different taxpayers receive the same lifetime income, those persons who save most will have a higher tax burden to bear. Furthermore, there can be no doubt that any tax system based on a traditional concept of this nature would be a serious hindrance to a country’s economic development. If it is decided to structure the system on the basis of the citizen’s ability to pay according to his lifetime income, the income tax can prove to be simple, equitable and efficient from the standpoint of a market economy. Two methods can be used in order to implement the taxation of lifetime income : savings adjustment and interest adjustment. In view of the administrative problems involved, together with aspects of international harmonisation of income taxation, we recommend the savings-adjusted method only for the taxation of pensions. All other types of capital income, including enterprise profits, can be taxed very simply using the interest-adjusted method. The application of a uniform tax rate guarantees that the implementation of income taxation is extremely simple and that the resulting single lifetime burden is fully transparent. 1. Factors determining the definition of taxable income from an economic standpoint The best definition of taxable income from an economic standpoint can be derived from what are considered to be the desired and real effects of income taxation. It is a question of establishing a basic approach to resolving the problem of which taxes should be levied in a market economy and in which form. In order to answer the first question with regard to the effects a tax must have, we must consider the tasks which society expects the state to fulfil and which require financial resources. 3 From the state citizens expect the provision of goods that are not supplied on the private market or whose supply there is inadequate, such as domestic security through police and the penal system, defence of the nation through the maintenance of an army, efficient systems of public transport and education, and a guarantee of law and order in economic transactions; together with the provision of income when the citizen is not able to cover his own basic living costs through unemployment, inability to work as a result of illness or old age. , The administrative function of taxation is to provide state organs with the funds they require in order to carry out the tasks with which they have been entrusted. This is generally recognised to be main function of taxation, which from an economic standpoint is a very short-sighted approach. The limitation of the objectives of taxation to its financing function can be shown to be responsible for the state’s inability to organise the efficient provision of public goods or to generate an adequate flow of revenue. In order to identify the primary function of taxation from an economic standpoint, note must be taken of the fact that the provision, in most cases free of charge, of public goods for citizens and business enterprises is impossible without the transfer to the state of real resources from their previous application in the private sector for use in the public sector. In other words, if citizens expect to be supplied with certain public goods, they must be prepared to forego a corresponding quantity of private goods. These may be current private consumer goods or capital goods. Capital goods will increase capacities to manufacture goods in the future and in general it would not make sense to forego their production in order to concentrate on the provision of public goods. In other words, in order to fulfil our wishes with regard to the provision of public goods, we must be prepared to forego the consumption of private goods. By abstaining in this way from consumption, resources are freed for the production and provision of public goods. Every year, every society must resolve a fundamental problem of distribution – economists refer to the problem of resource allocation. The goods and services that are produced using available resources in the form of labour, land and equipment (machines, etc.) – gross national product – must be broken down into private goods (consumer and capital goods) on the one hand and public goods (consumption and investment) on the other. Consumers are faced with a second distribution problem arising from the provision of income in the case of unemployment, illness and old age: those who are employed must 4 forego consumption in order to achieve a satisfactory level of consumption for those who cannot work. This second distribution problem is usually regarded as a problem for the state, whose task it is to convert the primary distribution resulting from market forces into a “better” secondary distribution pattern. In effect, it is a question of redistributing real consumption wishes. It is conceivable that in very small communities both distribution problems could be resolved by voluntary abstention from consumption on the part of each individual. In today’s large societies and economies based on the division of labour, however, such a solution is not feasible. We need state organs in order to guarantee the necessary reduction of private consumption possibilities. Should private consumption wishes be satisfied in general by the market and not through the distribution of consumer goods by the state, there is then only one possibility of resolving the two distribution problems: private purchasing power must be transferred to the state by means of taxation. If taxation leads to citizens abstaining from the consumption of private goods, it makes it possible for the resources that have been freed to be used for the production of public goods or the redistribution of consumption. We have thus finally identified the basic economic function performed by a tax in a market economy, namely to siphon off private purchasing power from the citizens. We now know what is desired of a tax from an economic standpoint, but what is the economic reality of taxation? This brings us to the second aspect of the basic problem we have already outlined, namely the question of the real effects of taxation. Some may be surprised to learn that according to research in this field, wishful thinking matches reality. The following basic law of tax effects holds true: The final burden of any tax, whatever its form and whoever may pay it, is always the sacrifice of consumption by an individual. A tax burden can only be borne by individuals. In this sense, all taxes can be said to be taxes on consumption. If all taxes are to be treated in the same way with regard to the nature of the fundamental effect of the burdens they impose, this does not hold with regard to the scale of their burdens. Taxes which by virtue of their special structures not only siphon off purchasing power but cause taxpayers to behave in ways that reduce the gross national product give rise to undesirable additional burdens, often referred to as dead-weight losses. Hence, if 5 taxes cause substantial distortions in the efficient functioning of the market economy by changing prices and altering behaviour, the economic costs of government expenditure will exceed the basic burden arising from the restriction of consumption possibilities forced upon citizens by taxation. The results of empirical research have shown that substantial additional burdens may arise from the taxation of income and profits against the principles of the free market1. All in all, we must conclude that taxes should be designed to siphon off purchasing power and not to cause distortions in the market economy by providing taxpayers with the wrong incentives2. In this sense, the English economist Nicholas Kaldor defined the essence of an efficient tax, namely a tax which imposes a minimum burden, as follows: „An ideal tax is one which succeeds in reducing a person’s spending power but without leading him to behave any differently from the way in which he would have behaved if he had not been taxed at all, but his spending power had been correspondingly smaller.”3 In other words, if both the real effect of a tax and its function lie in the sacrifice of consumption by an individual, it is vitally important to focus the tax as directly as possible on burdening consumption. If this does not happen, it must be assumed that, by virtue of the unavoidable burden on consumption, a tax will change the behaviour of market participants with the result that aggregate output will inevitably be suboptimal. In this sense, the taxation of enterprise profits must and can be structured in such a way that enterprises are given no incentive to reduce their investments for reasons of taxation. Investment is vital for the economic growth that will create new jobs and guarantee all citizens the protection of their income in old age Furthermore, it would be detrimental to the welfare of society if a tax were to cause the taxpayer to change his decision with regard to the allocation of his available resources to current consumption and saving, i.e. consumption at some time in the 1 See, for example, Fehr / Wiegard (1999). It must be pointed out that in certain cases economists demand that a tax should not only reduce purchasing power but should also influence taxpayers’ behaviour. Here it is assumed that at current levels of production and consumption the functioning of the market is not optimal from the standpoint of the economy as a whole. If the environment is polluted by the use of certain production inputs or the consumption of certain goods and these costs are not included in the price of the goods, the economist recommends the introduction of a tax on these goods. This artificial increase in price steers demand in the direction of other goods that are less harmful to the environment. For the theoretical basis of such price-correcting policies see Sohmen (1976), chapter 7 and Boadway / Wildasin (1984), chapter 5. 3 Kaldor (1965), p. 81. 2 6 future. It is also possible to avoid this distortion by structuring income taxation accordingly. Finally, it would be detrimental to citizens and society in general if a tax were to sway decisions regarding the supply of labour in favour of leisure. With the exception of the poll tax, which does not come into consideration here, every tax in effect artificially renders untaxable leisure cheaper and the supply of labour more expensive4. It is, however, impossible to structure taxes, including the income tax, in such a way that the additional burdens of this discrimination are kept to a minimum. This can be explained mainly by the fact that it has not yet been possible to quantify these burdens for the purposes of tax laws. The additional burdens arising from the unavoidable tax discrimination of the supply of labour can only be limited in practice by the choice of a tax rate that is as low as possible. The tax effects that have been described so far do not comprise all the effects that must be considered in the development of a concept of taxable income that is adequate from an economic standpoint. The effects of the implementation of taxation must also be taken into consideration: for the state there are the administrative costs associated with a tax, for citizens and business enterprises there are the costs of compliance. In selecting the best possible concept of income, therefore, one should ensure that the implementation of income taxation is as straightforward as possible. A final aspect relates to the judgement of tax effects according to whether tax burdens can be regarded as equitable. I prefer to assign these claims to the criterion of fair taxation. The concept of tax equity is often reduced to the equitable distribution of tax burdens. Equitable taxation, however, goes beyond that and is also bound up with the demand that the state and society as a whole must treat the individual taxpaying citizen fairly. The question then arises as to when a citizen can be considered capable of being taxed. This issue is resolved with the help of the well-established criterion of ability-to-pay, together with the principle that citizens with equal ability-to-pay should bear the same tax burden and that an increase in ability-to-pay justifies an increase in the tax burden. In this sense, the criterion of equitable taxation is identical with the criterion of taxation according to ability-to-pay. In this case, it has proved useful to interpret this criterion in two stages. The starting point is an ability to pay taxes based on the availability of economic purchasing power. Here we can speak of economic ability to pay. The desire to guarantee a citizen’s 4 The extraordinary burdens arising from this distortion of decision-making are the subject of an extensive body of economic literature. See, for example, Sandmo (1976), Auerbach (1985). 7 right to subsistence has led to the demand that a certain basic stock of economic means should not be diminished by taxation. We have thus progressed from an economic abilityto-pay to a reduced ability-to-pay for which the literature, in my opinion, has not yet found a suitable term. As there is reference to protection from the imposition of an inhumane burden on a citizen’s subsistence requirements, I should prefer to speak of humane abilityto-pay. Up to this point there should be broad agreement on the interpretation of the term “ability-to-pay”. This is no longer likely to be the case when it is a question of putting the term to use in practice. It will then have to be satisfy the following purely formal criteria: it must give rise to an unambiguous, quantifiable result; it must facilitate the objectively comprehensible comparability of individual citizens; and it must be capable of practical application in the context of the unambiguous provisions of the laws governing taxation. The notion of income in the sense of the traditional concept of the annual increase in wealth5, for example, does not satisfy these criteria. The first uncertainty is raised by the familiar question of whether unrealised changes in wealth should be included together with realised changes when determining the increase in wealth for a period. From an economic standpoint there can be no doubt that unrealised changes in wealth must also be taken into consideration. If for practical reasons only realised wealth increases are included in the tax base, this will mean that equal wealth increases – one realised, the other not – do not receive the same treatment. In many cases it is even quite impossible to determine the change in wealth. This is true, for example, of an increase in wealth resulting from an investment in education, also referred to as the formation of human capital. The increase in wealth here takes the form of the higher incomes that will be possible in the future as a result of the new skills that have been acquired today through education. In the enterprise sector there is also an insoluble problem with regard to assessing the values of changes in wealth. The problem relates to the decrease in wealth due to the use of long-term fixed assets. In view of the fact that, when faced with this problem, even business managers capitulate and resort to arbitrary accounting conventions, it comes as no surprise to learn that those responsible for framing taxation laws have not been able to think of anything better. It was for this reason that taxable profits came to be assessed according to the provisions of commercial law in Germany and a few other European countries. In the meantime, legislators in Germany have also come round to the view that commercial law is hardly an adequate basis for the law governing taxation. This is in no sense a reproach, since the ambiguity of the traditional concept of income allows the change in the value of 8 long-term fixed assets to be determined according to the principle of arbitrariness. This, incidentally, is also the case when it is decided not to tax the implicit rent received from owning one’s home and the build-up of wealth in life insurance policies. By now there should no longer be any doubt that the traditional notion of income is totally incapable of meeting the criteria of unambiguity and interpersonal comparability that must be satisfied by an acceptable concept of economic ability to pay. It is not only for these reasons that the concept of income according to the traditional income-tax model must be rejected. It is a well-known feature of the traditional concept that the source of income must be disregarded. The result is that incomes derived in the same year from capital and from work are considered to be the same kinds of income which should be treated in the same way, i.e. the tax paid on each of these items should be the same. The fact is ignored that income arising from work today is the result of today’s performance at work, whereas today’s flows of capital income are the result of interest borne by income that has been earned at an earlier point in time and taxed before being invested. It is not difficult to prove that the apparently equitable treatment of incomes from capital and work in fact gives rise to different tax burdens6. It is a fact, moreover, that, for a person who saves and receives income from his capital the tax burden will always be greater than the tax rate laid down by law and will increase as the savings period increases. This constitutes an incentive for the citizen to reduce his savings and spend more of his current income immediately on consumption, with all the inevitable negative consequences for the economic development of the country. As company profits are also considered to be capital income, their taxation unavoidably curbs corporate investment. Company profits have a particularly excessive burden to bear if the entrepreneur, in his desire to provide himself with resources for consumption in his old age, has set up his enterprise in the legal form of a public limited liability company. Should he sell his shareholding, he will have to pay income tax on the resulting profit which, from an economic standpoint, has arisen from his investing profits that have already been taxed. If the investment period is sufficiently long, with a corporate income tax rate of 40% and a personal income tax rate of 40%, the effective tax burden on company profits can exceed 80%. The effects on tax burdens of the arbitrary determination of depreciation for tax purposes have a further impact on taxpayers’ behaviour. The ranking of investment opportunities 5 This concept dates back to Schanz (1896), Haig (1921) und Simons (1938). See the calculations of burdens by Joachim Lang on pages 16 ff. of his conference paper and Rose (1997, 1998). 6 9 according to market opportunities suffers massive distortion as a result of the legal provisions for determining profit for purposes of taxation. Those responsible for framing tax policy feel obliged to intervene and thus complete the preordained tax chaos that is inherent to the system. In order to satisfy as far as is possible the demands for an income tax system that is neutral in its impact on decision-making, simple and equitable, there must be a fresh approach in the choice of a concept of income for the purposes of taxation. As a new model I suggest the application of the concept of economic ability-to-pay through the economic concept of lifetime income. This makes it possible to complete quite naturally the second stage of the ability-to-pay, namely the transition to taxation of humane ability-to-pay throughout a citizen’s life. 2. The economic notion of lifetime income as a guideline for the notion of taxable income 2.1 The citizen’s lifetime income from an economic standpoint A person’s lifetime income is defined as the sum of all income surpluses compounded until the end of his life arising from the transfers and market activities of all years plus the estate he leaves for disposal at his death. An income surplus in this sense is the difference between incomes and the expenses incurred in generating these incomes. Expenses also comprise the costs incurred in the acquisition of capital claims (interest-bearing securities or bank deposits) together with the costs of acquiring shares of enterprises. Both reduce the income surplus in the year in question. In the same way, all revenues generated by the sale of capital claims and shares of enterprises constitute income and raise the respective income surplus for the period in question. On the expenditure side lifetime income is the sum of compounded annual spending on consumption, gifts, tax payments and the estate left by the deceased. The interest rate to be used for compounding is the rate offered on the market for riskless capital investments. In the following example I have assumed for reasons of simplicity that there is only one such interest rate which remains constant for the two periods under observation. In the case of the 5% interest on both government bonds and pension contributions that have been paid in, it is assumed that this was not paid out during the lifetime of the person concerned and is therefore part of the estate that was available as cash at the end of the second period, in which the taxpayer died. 10 Determination of lifetime income (all amounts in euros) Period 1 Wages from dependent employment: 30 000; consumption expenditure and income tax payments: 20 000; contributions to a pension insurance fund: 4 000; purchase of government bonds: 6 000; Creation of the revenue surplus: [30 000– 4 000 – 6 000 = ] 20 000; Use of the revenue surplus: 20 000. Periode 2 Wages from dependent employment: 14 500; consumption expenditure and income tax payments: 12 000; contributions to a pension insurance fund: 2 500; Creation of the revenue surplus: [14 500 – 2 500 = ] 12 000; Use of the revenue surplus: 12 000; Estate of deceased: [(1,05*6 000 =) 6 300 + (2 500 + 1,05*4 000 =) 6 200 = ] 13 000. Lifetime income: [(1,05*20 000 =) 21 000 + 12 000 + 13 000 =] 46 000 2.2 The notion of taxable income corresponding to the notion of lifetime income The segregation of income elements that have already been burdened and that will be taxed at some time in the future A concept of lifetime taxation requires the annual taxation of income to be so designed that the tax burden on income which is considered to be taxable should be exactly equal to the established tax rate, never higher and never lower. The annual flow of incomes generated by market activities must be checked in order to determine whether they already have a tax-burden history, i.e. whether any these funds have already resulted in a tax burden for the taxpayer. If this is the case, they must be excluded from taxation in order to avoid a multiple tax burden on the same income. Income received shall be tax-free if it is used to generate future income and if the taxation of such income in the future is guaranteed. In this sense, all expenses incurred in the acquisition of interest-bearing capital claims or shares in enterprises can be regarded as deductible, since they represent amounts that have been saved by the citizen from his inflow of income. From an economic standpoint, the 11 subsequent sale of capital claims or shares of enterprises and the use of the resulting income to finance consumption expenditure constitutes dissaving. In this respect we can here refer to the method of savings adjustment of the tax base. The above example of determination of lifetime income serves to illustrate the tax burden on lifetime income determined by applying the method of savings adjustment to annual income. In the case of the employee in question, it is assumed that the subsistence level of consumption to be protected is 8,000 euros. On this basis his lifetime income can be calculated according to the concept of humane ability to pay. In order to simplify matters, the same tax rate of 25% applies for both periods. The respective annual tax base corresponds to the respective annual revenue surplus given above. In order to calculate the lifetime tax burden, the compounded annual tax payments must be added together. Tax burden in the case of taxation of the savings-adjusted annual income (all amounts in euros) Period 1 Tax base: [20 000 – 8 000 =] 12 000; tax payment: 3 000 Period 2 Tax base: [12 000 + 13 000 – 8 000 =] 17 000; tax payment: 4 250 Lifetime income tax: [1,05*3 000 + 4 250 =] 7 400. Lifetime income according to the concept of humane ability-to-pay: [1,05*(20 000 – 8 000) =] 12 600 + [(25 000 – 8 000) =] 17 000 = 29 600 Tax burden on lifetime income: [100*(7 400/29 600) =] 25 % The most important result of this calculation is the fact that the effective tax burden tallies exactly with the tax rate established by law. For the implementation in practice of a lifetime income tax it is extremely important to know that the desired tax burden can also be achieved by another method. This does not permit the deduction of expenses incurred in the acquisition of interest-bearing capital claims and shares in enterprises. On the other hand, tax shall be levied only on that part of income from such capital investments that arises from interest rates which exceed normal 12 market rates. In practice all capital incomes are adjusted according to the standard rate of interest, hence we can here refer to the method of interest-rate adjustment of the tax base. In our modest example we have considered only capital investments bearing a normal market rate of 5%. This means that all interest payments must remain tax-free. Taking into consideration the fact that a subsistence consumption level of 8,000 euros must be protected, this results in the following tax payments and burdens: Here too the effective tax burden tallies exactly with the tax rate established by law. The savings-adjusted and interest-adjusted methods result in the same tax burden, even though there are differences in the distribution of tax payments over time. This no longer holds if a progressive tax scale is applied according to which the tax rate increases with the tax base7. Nevertheless, even with such a tax scale, the annual contribution to lifetime income is only subjected to a single tax burden with either of the two methods. Tax burdens in the case of taxation of the interest-adjusted annual income (all amounts in euros) Period 1 Tax base: [30 000 – 8 000 =] 22 000; tax payment: 5 500 Period 2 Tax base: [14 500– 8 000 =] 6 500; tax payment: 1 625 Lifetime income tax: [1,05*5 500 + 1 625 =] 7 400. Lifetime income according to the concept of humane ability to pay: [1,05*(30 000 – 8 000) =] 23 100 + (14 500 – 8 000 =] 6 500] = 29 600 Tax burden on lifetime income: [100*(7 400/29 600) =] 25 % The segregation of transfer incomes A citizen’s lifetime income comprises not only income generated by market activities but also sums received without any quid pro quo. Such payments, which may come from state organs or from other citizens, are referred to by economists as transfer payments. 7 What is meant here is the increase in the marginal tax rate with the tax base. 13 Transfer payments are generally made by the state – in the form of supplementary welfare benefits, for example – in situations where the citizen receives too small a market income or none at all. If such transfers were subject to taxation, they would have to be high enough for the unemployed person to be able to pay his income tax and then finance his necessary subsistence consumption from the remaining sum. If in addition there were a basic taxfree allowance to protect the level of subsistence consumption, state revenues from taxation would in this case be reduced to zero. For reasons of simplicity transfer payments made by the state should be regarded as net income and therefore, of course, not subject to taxation. Now we come to the much more difficult question of whether transfer payments made by one citizen to another should be subject to taxation. If the answer is yes, it is evident that the raising of the recipient’s taxable ability to pay should correspond to a lowering of the donor’s taxable ability to pay. According to this principle of correspondence, the taxation of the recipient’s transfer income should correspond to a tax deduction of the same amount in favour of the donor. If we examine the principle of correspondence with regard to the question of whether inheritance and gifts should be regarded as part of a person’s taxable lifetime income, we come to the following conclusion: from a technical standpoint it would undoubtedly be possible to include inheritance and gifts in the recipient’s taxable lifetime income as transfer payments. It would then be necessary, however, to consider gifts as a reduction of the donor’s taxable lifetime income. If he had other forms of income to compensate this deduction, the consequence from a fiscal standpoint would be a decrease in tax revenues. This would correspond to the increase in tax revenues resulting from the taxation of the recipient’s gift. All in all, with a standard tax rate there would be no increase in tax revenues for the state. If the donor had no other taxable income, i.e. if the gift were part of his taxed savings, he would have to receive a tax refund from the tax authorities. Quite apart from the thorny problem of assessing the values of different forms of wealth, it is already clear that it does not make sense to tax gifts within the framework of the taxation of lifetime income. This argument is even more valid in the case of inheritance, which in most cases represents a transfer from the taxed savings capital of the deceased. On the one hand the heir would have to declare the inheritance as income to be taxed and on the other he would receive a refund of the tax paid by the testator on the incomes with which the inherited wealth had been accumulated. It is all too clear that this would give rise to a highly complicated taxation procedure but, in the end, no significant tax revenues for the state. It is even possible that the heir’s tax refund would be more than 14 the amount of tax that he had to pay. With a progressive tax scale the testator may well have paid tax in the upper tax brackets, whereas the heir would pay tax on the inheritance at a lower tax rate. On these grounds alone one cannot recommend the inclusion of gifts and inheritance within the framework of lifetime income taxation8. A further reason for not including gifts and inheritance in the recipient’s tax base is the impact the taxation of transfers will have on the donor. If the donor’s motive in devoting his income to gifts and inheritance is to transfer consumption possibilities, he must compensate for the tax to be paid by the recipient by increasing the transfer by a corresponding amount. This would mean, however, that in the end he would bear the burden of a tax that he has not paid himself. The result would be a double tax burden for income devoted to gifts or inheritance, which could not be justified. If a separate tax were to be levied on gifts and inheritance, this would also require separate justification. In the case of such a tax that respects neither the principle of correspondence nor the principle of avoidance of multiple taxation, the result is in fact to transfer to the state private wealth that has been accumulated from taxed income. This can only make sense – if at all – if the wealth that has been taken from citizens is given back, preferably to those persons who, in view of their inadequate market income, have no chance themselves of building up a stock of wealth for their old age. Unfortunately, it is not possible to pursue this important issue further within the framework of this paper. Finally, some reference must be made to the payments imposed by law for the maintenance of extramarital children, divorced spouses and their children, and other persons. With a standard tax rate and assuming the maintenance payer were to take advantage of all relevant tax-free allowances for maintenance, it makes no sense to deduct the transfer in the case of the payer and to tax it in the case of the recipient. With a progressive tax scale however, the result would be different. In this case the maintenance payer would have to be entitled to deduct the payments and the recipient obliged to pay tax on them. As the transfers in question are designed to safeguard the recipient’s livelihood, they could be taken into consideration as personal deductions from the payer’s market income. The recipient would have to declare the income received as personal remunerations and pay tax on it accordingly9. For the structuring of a tax on the basis of a citizen’s annual 8 As we shall see in Section 3, in the case of a decision for administrative reasons to forego the taxation of estate according to the savings-adjusted concept, it must be ensured that, should the beneficiaries make withdrawals from the estate for consumption purposes, they will pay tax on income in an amount corresponding to the respective withdrawal. 9 For such a concept see Lang (1993), pp. 157. 15 contribution to his lifetime income only income from market activities is to be taken into consideration in the formation of the first stage of the tax base – according to economic ability to pay. In so far it is possible to speak of the concept of taxation of marketdetermined lifetime income. 3. Evaluation of alternative systems of taxing lifetime income 3.1 Decision neutrality It is important to note that, compared to the traditional method, i.e. the non-adjusted approach of taxing personal income and enterprise profits, neither the interest-adjusted system nor the savings-adjusted tax system discriminate against any kind of saving, which leads to a form of income taxation that is neutral with respect to its effects on intertemporal decision-making. Furthermore, the traditional tax on business profits does not guarantee decision neutrality with respect to business investments. This arises mainly from the effect on the profitability of investment of the method of depreciation applied. The crucial point here is that accelerated depreciation will postpone tax payments, which will be an incentive for the investor, who will be provided with more liquidity and will thus be able to reduce his bank credit or place the funds in capital markets. The cost of the investors’ capital is reduced by more accelerated schemes of depreciation but, on the other hand, this implies that the government loses money because interest has to be paid on additional public debt. If the savings-adjusted method is applied in the taxation of lifetime income, these problems disappear completely because enterprises are considered as special saving accounts and no tax is imposed as long as profits are retained and used for business purposes. Decision neutrality with respect to business investment is also guaranteed by applying the interestadjusted method of taxing lifetime income. The calculation of taxable profits according to the principles of cash accounting would ideally require the full deduction of expenses for long-term fixed assets. From a fiscal standpoint, by treating the total amount of investment as an expense in the year it is made, which is essential for a cash-flow tax, the tax base is reduced substantially at the beginning of the investment period and the settlement of tax liabilities is delayed until some later date. If this were not permitted but instead yearly deductible depreciations had to be made for fiscal reasons, i.e. in order to guarantee earlier tax revenues for the state from this source, a provision would be required in order to ensure 16 that enterprises were fully compensated for this disadvantage. Such a provision would entitle investors to deduct all the costs of financing their investments, which would comprise interest on both debt and equity capital. Based as it is on this deduction, the interest-adjusted taxation of business profits is a guarantee that the method of depreciation will have no effect on the present value of the deductible cost of capital. This is a precondition for the required decision neutrality with respect to business investments. The reason for this is that tax savings arising from accelerated depreciation automatically lead to a lower book value for equity capital and this in turn reduces the additional deductions for imputed interest on equity capital. For companies whose capital costs coincide with the market interest rate, the two effects cancel each other out. In the end, the interest-adjusted taxation of business profits has the same economic effect as applying Hall/Rabushka’s (1995) ‘flat tax’, which treats the total amount of investment as an expense in the year it is made. Of course, annual tax revenue differs according to which of the two methods of taxing income from business investment is applied. If, however, the tax rate and rate of interest are constant, the present value of total tax revenue for the entire period of investment is the same. 3.2 Administrative efficiency We now come to the question of how the two alternative methods of taxing income are to be evaluated with respect to the criterion of administrative efficiency, i.e. simplicity. With regard to the administration of the savings-adjusted system, several monitoring problems must be solved in order to ensure the taxation of income. A procedure must be established, for example, to record and control the use of assets held in qualified savings accounts10, for it must be ensured that assets recorded at banks and similar financial institutions are taxed if they are sold and these proceeds are used for consumption. Administrative measures of this kind are also important because of the need to ensure that all assets on accounts recognised by the tax authorities as being eligible are taxed if the taxpayer clears them in order to transfer his domicile abroad. In addition, both the contribution of equity capital into enterprises and withdrawals from them are to be monitored irrespective of the legal status of the enterprises. Problems will also arise within the framework of double-taxation agreements, because the definition of taxable income 10 For the concept of qualified accounts and legal aspects see Lang (1993), p. 163. 17 differs substantially from the definition used in the OECD Model Tax Convention for double-taxation agreements. By contrast, the interest-adjusted personal income tax is much easier to administer because it reduces the number of different kinds of income that are traditionally taxable. Furthermore, exempting normal interest income from taxation creates no conflict within the conventional framework of avoiding the double taxation of cross-border capital income. 3.3 Taxation versus tax burdens Another aspect that is both administrative and economic in nature affects the taxation of estate applying the savings-adjusted method. If we take lifetime income taxation to mean that the taxation of all taxable components of income must be completed within a person’s lifetime, those inheriting the estate would have to sell it and make, on behalf of the testator as it were, a last tax payment from the proceeds. If, however, the forced sale of the estate is not provided for by law – and it is difficult to imagine another state of affairs – those who have inherited the estate will be faced with both a liquidity problem and a problem of evaluation. These problems are particularly thorny when an inheritance involves an enterprise whose shares are not traded on the capital markets. The taxation of the stock of wealth at the end of a person’s life represents a departure from the principle of income determination on the basis of cash accounting, which has been employed throughout the taxpayer’s lifetime. Inevitably there will also be a breach of the principle of horizontal equity, since the solution of the beneficiaries’ liquidity problem depends on the types of wealth they have inherited and the liquid funds currently at their disposal. If the taxation of lifetime income is not bound to the taxpayer’s lifetime, there is neither a problem of valuation nor a liquidity problem for his heirs. If with regard to the effect of taxation it is merely a question of ensuring that each part of a taxpayer’s income should only bear a single tax burden, when it is taxed is of no consequence. The question then arises as to the market value of estate that has been accumulated in the taxpayer’s lifetime as a result of his investing tax-free income in qualified savings accounts. If it is certain that any withdrawal from this hitherto tax-free area will always be subject to taxation, the market value of a qualified savings account will be lower than the sum of the market values of individual items of wealth by a percentage that is equal to the tax rate. Nobody would buy an enterprise, for example, at the market value of its individual assets if each 18 subsequent withdrawal from the enterprise were subject to taxation. This makes it clear that, with an savings-adjusted system of income taxation, estate has already been burdened by taxation when it is inherited. For those who have inherited the estate this constitutes an inflow of taxable funds which, however, does not immediately give rise to a tax payment, providing the inherited qualified bank accounts are added to their existing qualified accounts. The fiscal consequence of such a solution is that is left to the taxpayer’s heirs to decide when, if at all, the estate is to be taxed at a later point in time. In comparison, the interest-adjusted method of annual capital income taxation can be judged much more favourably from a fiscal standpoint. This is explained by the fact that in this case the savings capital has been accumulated from income that has been taxed. The problem of the taxation of capital gains is also much easier to resolve if the profits of companies that are quoted on the stock exchange are finally taxed at company level. In this case, the profits from the sale of the shares of such companies should not be taxed, in order to ensure that enterprise profits only bear a single tax burden. If the value of the holding (e.g. a share) has gained in value because the enterprise has invested taxed profits, taxation of the gains on disposal would result in double taxation of the same profits. If the enterprise is expected to make a profit in the future and the market value of a shareholding increases as a result, the seller will be burdened not by taxes in the past but by the prospect of future taxes on future profits. The person acquiring the holding will be able to transfer to the seller the tax burden on his share of the future profits of the enterprise by marking down the acquisition price. Gains on disposal that are of a purely speculative nature and are not justified by profits to be generated by the enterprise in the future could be taxed if it were possible to identify them as such. As the future is a closed book, however, this is technically impossible. As unjustified gains on disposal lead to losses on disposal for a later shareholder, they must be fully deductible from his tax base. For the tax authorities the result is worse than that of a zero sum game if one takes into account the collection costs associated with gains and losses on disposal. 4. The simplest method of taxing lifetime income The above descriptions of the advantages and disadvantages of a system of taxing annual income that satisfies the fairness criterion of a single tax burden on lifetime income leads us to the conclusion that, for both administrative and fiscal reasons, the interest-adjusted method is clearly superior to the savings-adjusted method. In this case, interest is only taxed in so far as it exceeds the yield from a capital investment at normal market rates. 19 Normal market interest rates shall be understood as the effective interest rates on interestbearing capital claims which do not exceed the rate of protective interest for the same period. The protective interest rate is the rate of interest on a riskless capital investment. As there are several different interest rates on the capital market, some standardisation is necessary. In this sense the average interest rate on government bonds could serve as a legally binding approximation of the protective interest rate. Interest rates that exceed the rate of protective interest can also be regarded as normal if the interest is paid on bonds for which a wide public was invited to subscribe at the time they were issued and which were subsequently widely transferred. This means that only on very rare occasions does a citizen’s capital income arise from interest-bearing investments subject to taxation. It should be stressed that tax-free interest is not a privilege from a lifetime point of view. It is an arrangement designed to avoid the multiple burden borne by interest from income saved and invested in bonds or saving accounts at banks. Corresponding to this we have the exemption from taxation granted to normal market returns on equity capital at the level of protective interest, i.e. when taxed income is saved and invested in enterprises. The investor’s protective interest is twinned with the private saver’s exemption from taxation. Marginal and Average Tax Rate of an Interest-adjusted Profit Tax - Marginal tax rate: 25%, Protective rate of interest: 5% - Marginal Tax Rate 25,00% 20,00% 15,00% Average Tax Rate 10,00% 5,00% Gross Rate of Return on Investment 35,00% 30,00% 25,00% 20,00% 15,00% 10,00% 5,00% 0,00% 0,00% 20 As is illustrated by the above graph of the marginal tax rate and the average tax rate of an interest-adjusted profit tax, the principle of taxation according to ability-to-pay is fully respected. As long as the return on an investment does not exceed the basic protected rate, it will not be taxed. Only when the return on an investment exceeds the rate of protective interest does it become liable to taxation. However, as in the case of the protection of the citizen’s subsistence level of consumption, tax is levied only on that part of the returns on an investment which exceeds the rate of protective interest. If the tax is related to gross returns on the investment, the average tax rate is obtained. This remains at zero up to the level of the rate of protective interest before approximating degressively to the marginal tax rate without ever actually reaching it. The slope of the average-tax-rate curve, with respect to the tax period in question, is an indication that the tax burden is positively related to the enterprise’s ability-to-pay. Furthermore, indexation is definitely not necessary in order to adjust the tax base for inflation. When a profit corresponding to the nominal interest on equity - up to a standard rate which contains the rate of inflation - remains tax-free, illusory paper profits do not form part of the tax base. It is important to point out that an interest-adjusted enterpriseprofit tax automatically ensures that the illusory profits which inflation usually brings about are not taxed. The procedure of adjustment is simple with respect to both compliance and auditing. There is a further issue, however, which should be taken into account when an integrated system of taxing personal income and enterprise profit is developed. Personal taxable income throughout a citizen’s life is the precondition guaranteeing that his subsistence level of consumption remains tax free during his lifetime. Taxing personal income and enterprise profit exclusively within the framework of an interest-adjusted system would result in tax-free pensions and thus force the pensioner to finance his subsistence level of consumption from taxed income. This would be unfair and violate the principle of humane ability-to-pay. The savings-adjusted approach should thus be used to tax income from pension funds uniformly in order to guarantee that the subsistence minimum is left unburdened throughout the citizen’s lifetime.. All persons receiving income should have the possibility of putting aside savings that are tax-free in order to provide for a pension in their old age. For this to be possible, enterprise profits should be taxed as far as is possible at the level of the owner or shareholder, where these are natural persons. This would make it desirable to levy personal income tax on the 21 profits of both partnerships and private limited liability companies (GmbHs, etc.). At the same time this would mean that the economic requirement would be satisfied according to which the profits of enterprises should be subjected to equal burdens regardless of the legal status of the companies concerned. If, in the case of income taxation, the meaning of simplicity is taken to include transparency with regard to the tax burden, this requirement can best be satisfied by applying the same standard tax rate for both the personal income tax and tax on the profits of public limited liability companies.11 References Fehr, H. / Wiegard, W. (1999), Lohnt sich eine konsumorientierte Neugestaltung des Steuersystems?, in: Smekal, C. / Sendlhofer, R. / Winner, H. (eds.): Einkommen versus Konsum, Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, 1999. Boadway, R. W. / Wildasin, D. E. (1984), Public Sector Economics, 2. edition, Little Brown, Boston. Sohmen, E. (1976), Allokationstheorie und Wirtschaftspolitik, J. C. B. Mohr, Tübingen. Sandmo, A. (1976), Optimal Taxation, An introduction to the literature, Journal of Public Economics, 6, pp. 37-54. Auerbach, A. J. (1985), The Theory of Excess Burden and Optimal Taxation, in: A. J. Auerbach / M. Feldstein, I, pp. 61-127. Rose, M. (1998), Recommendations on Taxing Income for Countries in Transition to Market Economies, in: Rose, M. (ed.): Tax Reform for Counties in Transition to Market Economies, Lucius und Lucius, Stuttgart, 1998. Rose, M. /Wiswesser, R. (1998), Tax Reform in Transition Economies: Experiences from Participating in the Croation Tax Reform Process of the 1990s, in: P. Sorensen (ed.), Public Finance in a Changing World, Houndsmill: Macmillan Press, pp. 257-278. Simons (1938), Personal Income Taxation: The Definition of Income as a Problem of Fiscal Policy, University of Chicago, Chicago. Haig, R. M. (1921), The Concept of Income - Economic and Legal Aspects, in: Musgrave, R.A. / Shoup, C.S. (eds.): Readings in the Economics of Taxation, London, 1959, pp. 5476. Schanz, G. von (1896), Der Einkommensbegriff und die Einkommensteuergesetze, Finanzarchiv, 13, pp. 1–87. For information on such a system of income taxation see the author’s information on the Heidelberg Simple Tax under www.einfachsteuer.de. 11 22 Lang, J. (1993), Entwurf eines Steuergesetzbuchs, Schriftenreihe des BMF, Heft 49, Stollfuß Verlag, Bonn.