Songhai

advertisement

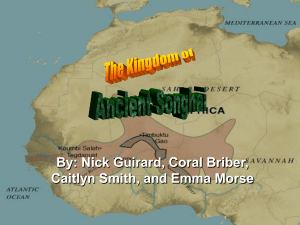

How the Songhai Empire Grew to Greatness Songhai was the last of the three great trading empires to emerge in West Africa. Over an 800 year period, the Songhai, who originally lived as fisherman and farmers on both banks of the Niger, slowly expanded their territory from a small settlement near the city of Gao to an empire that unified most of the Western Sudan. At the height of its power in the fifteenth century, Songhai was larger and wealthier than the kingdoms of Mali and Ghana combined. Just as Mali arose from the collapse of the empire of Ghana, Songhai developed as the power of the Malian empire declined. The first large city in Songhai was Kukya. Berbers from the Sahara captured Kukya in the mid-1400s and renamed it Gao. Because of its strategic position on the Niger, Gao became an important center of commerce. From the eleventh through the fourteenth centuries, the Songhai leaders at Gao struggled to protect their kingdom from attacks by Mali. Finally in the early 1300s Gao and must of the Songhai Kingdom were brought under Malian control by Mansa Musa. In 1435, two Songhai princes, Ali Kolan and Sulayman Mar, declared Gao’s independence from Mali. These brothers successfully fought off Mali’s attempts to regain Gao and founded a new succession of rulers called the Sunni. In 1464, Ali Kolan now known by his new title, Sunni Ali, embarked upon the systematic conquest of the territories held by Mali. One of the first cities Sunni Ali gained control of was Timbuktu. Next, he conquered the nearby city of Jenne and married the Queen there. Jenne’s capture and the union of its royal family with Sunni Ali’s in 1483 was the victory that helped Songhai replace Mali as the greatest empire in the Western Sudan. Songhai reached its apogee under Askia Muhammad Touray a devout Muslim and visionary politician of Soninke origin. Askia rose to power in the 1490s through the support of those who opposed Sunni Ali’s son and successor, Sunni Baare who refused to convert to Islam and was intolerant of Muslims. Sunni Baare alienated influential Muslims, which led to his overthrow by Askia and his supporters. Once in power, Askia declared Islam the state religion of Songhai, and under his direction mosques were built throughout the Songhai kingdom. When Askia appointed Muslim judges, Kadis, in the kingdom’s largest districts, Muslims became a permanent political and social force in Songhai. Songhai’s borders and the influence of the message of Islam- expanded further in West Africa when Askia took his army in the far eastern parts of the Sudan. Conquests there brought the Sudan under the control of a single leader again, and led to Songhai’s growth as an empire larger than Mali had been at its height. To promote unity throughout his empire, Askia organized a strong central government. As king he established an order of precedence and protocol within the government and distributed palace duties among a group of ministers. A key member in the ministry was the hi-koi, the minister who commanded a large flotilla of canoes. A strong navy allowed Songhai to control the Niger River and tax the various kingdoms of the Western Sudan for nearly two hundred years. Other officials in Askia’s ministry included chiefs of tax collectors, foresters, woodcutters, and fisherman. Even business matters were kept in order by means of a large staff of market inspectors. The hierarchy of Askia’s political system was reinforced by its social structure, which had many aspects of a caste system. At the top of this social system were the descendants of the original Songhai people of Kukya. They shared political power with the king, enjoyed special privileges, and were kept apart from the general population. They were not allowed to marry outside of their own caste. Below the Kukya in caster were the free people (called “freeman”) of the cities and towns and the members of the army. At the bottom of the social system were war captives and slaves, who were not placed in the army but were put to work on farms. Askia was an enlightened sovereign who encouraged the development of learning and scholarship in Songhai. Scholars from all over the world traveled to the University of Sankore in Timbuktu to study the numerous Arabic manuscripts that were housed there. The works of ancient writers like Aristotle and Plato were translated into Arabic and made available for study at Sankore. The city of Jenne was another center of learning in the Songhai realm. It, too, had a university with thousands of teachers who lectured and conducted research in medicine, and more traditional academic subjects such as theology, law, grammar, rhetoric, logic, astronomy, history, and geography. Despite his remarkable achievements, the final years of Askia Muhammad’s reign were marked by family in-fighting. When he was ninety years old and blind, several of his thirty four sons who were not directly in line to inherit the throne conspired to exile their father from the kingdom. Eventually, Askia Musa who was Askia’s eldest son emerged as king of Songhai in 1538. Seven different leaders attempted and failed to assert their control over the Songhai Empire. These kings kept Gao under their immediate surveillance and tried to rule the more remote regions through governors appointed from surveillance and tried to rule the more remote regions through governors appointed from the ranks of their kinsmen or court favorites. These governors appointed from the ranks of their kinsmen or court favorites. These governors, who were more often interested in aggrandizing personal power than in protection the interests of their subjects, were ineffective, and the stability of the Songhai monarchy remained precarious Songhai’s monarchy was eventually toppled by an invasion from Morocco in the 1580s. The Conquest of Songhai by Morocco The misrule of Askia Muhammad’s successors helped to hasten the end of the Songhai Empire. Several of Songhai’s western provinces refused to acknowledge the authority of the ruling family at Gao and instead proclaimed their independence. Although all of the chiefs in these rebellious provinces were eventually deposed and replaced by the leaders at Gao, the bitter fighting decimated the Songhai army, reducing it to nearly half of its former size. Interestingly however the major threat to Songhai’s power did not come from these West African kingdoms, but from Songhai’s northern neighbor, Morocco. Morocco had long profited from the trans-Saharan gold-salt trade. Al Mansur, the sultan of Morocco, believed that his profits might be even greater if he controlled the sources of both salt and gold in West Africa. Furthermore, the sultan needed additional revenue to pay for Morocco’s large mercenary army. This army of highly trained hired soldiers was armed with expensive muskets imported from England. Al-Mansur viewed a military expedition into the Sudan as an opportunity to offset the expense of maintaining his army and its costly weapons. Starting in the 1580’s Al-Mansur began to make plans to attack territory controlled by Songhai. In 1586 the sultan began an offensive on Songhai by ordering 200 of his musketeers to seize the salt mines of Taghaza. The Moroccans found the mine deserted; its occupants had been warned in time and had fled. Askiya Al-Hajj the leader of Songhai, further hindered the interests of the Moroccans by introducing a policy that officially forbade people to trade with Taghaza while it was under Moroccan control. Thus, the Moroccans who had seized Taghaza were left virtually empty-handed. Furious with the loss of potential revenue from Taghaza, al-Mansur pressured Songhai to lift the ban. In January 1590 he attempted to intimidate the new leader of Songhai, Askiya Ishaq by sending him a letter that demanded that the Taghazan trade sanctions be lifted. Ishaq responded with an insulting reply, reiterating that Songhai would not reverse its decision. This response so angered al-Mansur that he resolved to send a military expedition to the capital of Songhai itself. Al-Mansur assigned some of his best troops for the expedition to the Sudan and placed them under the command of a Spanish Muslim, Judar Pasha. This force included 1,000 renegade musketeers 1,000 Andalusian Musketeers and 500 mounted musketeers. In addition, the musketeers were joined by 1,500 recruits with lances. Careful preparations were undertaken to provide sufficient water and food provisions as well as other supplies, including large quantities of ammunition for all 4000 soldiers. The expedition left Marrakesh in October 1590 and reached the Niger River at the end of Febuary 1591. About half of the troops did not survive the grueling trans-Saharan journey. When the remaining 2000 soldiers reached the edge of the Songhai Empire, their superior firepower allowed them to easily repulse sporadic attacks by Songhai archers. The Moroccans first conquered the city of Karabar and made preparations to advance towards the Songhai capital at Gao. In response, Askiya Ishaq and his army met them At Tondibi where the decisive battle took place. The Songhai army at Tondibi consisted of approximately 18000 cavalry and 100,000 infantry. At the start of the battle Askiya Ishaq ordered a herd of cattle to be driven in front of his army. This he hoped would cause disorder in the ranks of the heavily armed Moroccan force. But at the first volley of gunfire the cattle turned back and caused confusion in the Songhai army. The battle was over within a short time, as most of the Songhai were routed by heavy gunfire. Only the rearguard, a unit of brave and resolute warriors, did not retreat and continued to shoot arrows at the Moroccans until they were overcome in hand-to-hand fighting. The rest of the Songhai involved in the battle hastily retreated across the Niger. The Songhai army suffered heavy losses at Tondibi. Many people including civilians lost their lives while crossing the river in panic and confusion. Askiya Ishaq surrendered to al-Mansur and offered to pay a tribute of 100,000 pieces of gold and 1000 slaves. With his troops tired and stricken by disease, Judar Pasha wanted to accept Ishaq’s offer, refrain from attacking other parts of the Songhai Empire, and retreat from Sudan. Determined to control all of the Sudan, al-Mansur rejected the offer and sent another leader to replace Judar Pasha, with instructions to conquer Songhai and take control of Gao and Timbuktu. After the clash at Tondibi the Moroccans spent another 150 years in the Sudan, but never accomplished their goal of monopolizing the trans-Saharan gold-salt trade. Though the cities of Gao and Timbuktu fell to the Moroccans in 1593, they did not yield the riches the Moroccans had hoped for. Furthermore rebellions throughout the region formerly controlled by Songhai prevented the Moroccans from establishing their authority in the Sudan. Small, independent states were established throughout the region in the early seventeenth century, and Al-Mansur’s successors decided that gaining control of the Sudan was more trouble than it was worth. Thus, in 1618, Morocco abandoned its attempts to extract profits from West Africa. The leaders of the Moroccan army who remained in the Sudan were left to fend for themselves and acted at petty tyrants.