The Songhai Empire

advertisement

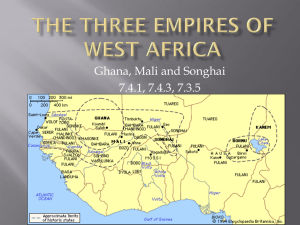

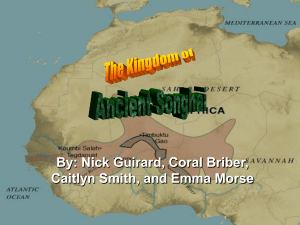

The Songhai Empire The Songhai Empire began when the Songhai king took advantage of a weakened Mali Empire to extend control over ever more territory. The Songhai people had long settled along the middle region of the Niger River, using the river for transport, fishing, hunting, and agriculture. By the ninth century this middle region of the Niger had been integrated into the state of Songhai, with its capital at Kukiya. Merchants traded with villages along the Niger and as far as the town of Gao, which had been founded by Berber and possibly even Egyptian merchants, attracted by the Bumbuk gold trade of Ghana. In 1009, the fifteenth king of Songhai converted to Islam and decided to live in Gao. Gao attracted Muslim merchants and scholars and became the most important settlement and commercial center and in due time the capital. It was in the fifteenth century, when the empire of Mali was greatly weakened, that Songhai was able to expand its territory. Sunni Ali Ber (Ali the Great) extended his rule from Gao to Timbuktu and Djenne in the mid-fifteenth century, and then conquered the whole kingdom of Mali, using a powerful army of horsemen and a fleet of war canoes. He made Songhai the largest and most powerful of all the Sudanese kingdoms. Eventually Timbuktu was restored to its former status as a great center of Islamic learning. Gao became a prosperous city of 10,000 inhabitants under Askia Mohammed Touré, a Soninke and devout Muslim. After his elaborate pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, he expanded the empire through a series of jihads (holy wars), extending his rule farther east to the Hausa states near Lake Chad and the Mossi kingdom to the south. He used Islam to reinforce his authority, to unite the farflung empire, and to revitalize trans-Saharan trade. He did not force Islam on the ordinary people, most of whom retained their traditional religious beliefs. Within a few years, the Songhai empire was considerably larger than Mali and occupied almost the entire western Sudan (see map of Songhai). The Songhai Empire survived and prospered by centralizing administrative power, revitalizing the trans-Sahara trade, and by using Islam as a unifying force. The administration of Songhai was more centralized than that of Mali. Traditional rulers were replaced by royal appointees who owed their positions directly to the king. The Songhai empire was divided into five large provinces, each with its own governor, Islamic courts, and professional fighting force to ensure that farmers of the province paid regular tribute to the king. The main sources of government income were thus tribute from the provinces, produce from the royal farms in the Niger flood plain and the Songhai heartland, and taxes on trade. Gold, kola nuts, and slaves were traded for salt, cloth, cowries, and horses. Cloth was woven from local Sudanese cotton and in towns like Djenne, Timbuktu, and Gao, woolen cloth and linen from north Africa were unraveled and re-woven to meet local tastes. The Songhai Empire collapsed when the Moroccans used superior weaponry to seize power and when maritime trade routes replaced trans-Sahara trade routes. The Songhai kingdom did not last long. The Moroccans seized the salt mines at Taghaza in 1585 and conquered Gao and Timbuktu, thanks to their gunfire which easily overcame the swords, spears, and arrows of the Songhai, even thought the latter had far larger numbers. Moorish soldiers occupied the Songhai cities, beginning a reign of terror that lasted well into the eighteenth century. The trade routes were no longer safe. Drought and disease also weakened the economy. In the east, the growth of Hausa states, Bornu, and the Tuareg sultanate of Aïr drew trans-Saharan trade away from Songhai and the western routes. The Songhai Empire broke into several separate states. As the Moorish civilization in North Africa declined, the demand for gold and other trade goods declined and trade became less lucrative. The Sahara became more of a barrier between the Sudan and Europe. Meanwhile the Portuguese began arriving in the Gulf of Guinea in the mid-fifteenth century and began trading with coastal Africans, first in gold (thus diverting gold from the trans-Saharan trade routes) and then in slaves.