Subversion of Public Space: A Study into Architecture and Graffiti

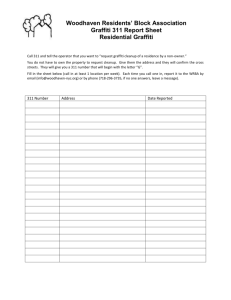

advertisement