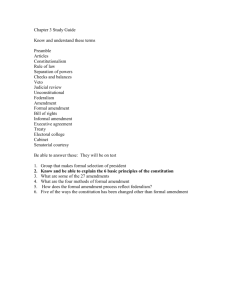

INTRODUCTION TO AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

advertisement