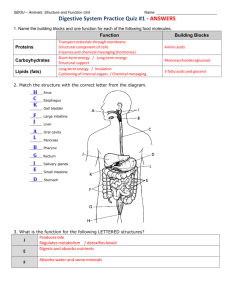

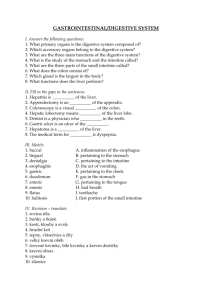

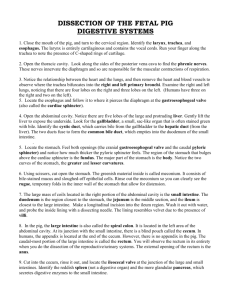

GI System

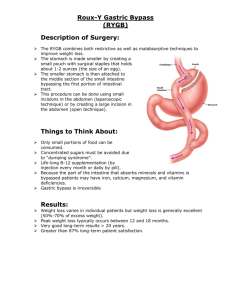

advertisement