Keystone Species

advertisement

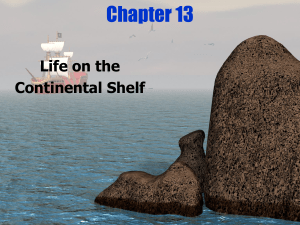

Charles C. Mann 1491: New revelations of the America’s before Columbus Adapted from pages 342-343 What happened after Columbus’s arrival was like a thousand kudzus everywhere. Throughout the hemisphere ecosystems cracked and heaved like winter ice. Echoes of the biological tumult resound through colonial manuscripts. Colonists in Jamestown broke off from complaining about the depredations of the rats they accidentally imported. Not all the invaders were such obvious pests, though. Clover and bluegrass, in Europe as tame and respectable as accountants, in the Americas transformed themselves into biological Attilas, sweeping through vast areas so quickly that the first English colonists who pushed into Kentucky found both species waiting for them. Peaches, not usually regarded as a weed, proliferated in the southeast with such fervor that by the eighteenth century farmers feared that the Carolinas would become “a wilderness of peach trees.” South America was hit especially hard. Endive and spinach escaped from colonial gardens and grew into impassible, six-foot thickets on the Peruvian coast; thousands of feet higher, mint overwhelmed Andean valleys. In the Pampas of Argentina and Uruguay, the voyaging Charles Darwin discovered hundreds of square miles strangled by feral artichoke. “Over the undulating plains, where these great beds occur, nothing else can now live,” he observed. A phenomenon much like ecological release can occur when a species suddenly loses its burden of predators. The advent of mechanized fishing in the 1920s drastically reduced the number of cod from the Gulf of Maine to the Grand Banks. With cod gone, the urchins on which they fed had no enemies left. Soon a spiny carpet covered the bottom of the gulf. Sea urchins feed on kelp. As their population boomed, they destroyed the area’s kelp beds, creating what icthyologists call “sea urchin barrens.” In this region, cod was the species that governed the overall composition of the ecosystem. The fish was a “keystone” species: one “that affects the survival and abundance of many other species,” in the definition of Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson. Keystone species have disproportionate impact on their ecosystems. Removing them, Wilson explained “results in a relatively significant shift in the composition of the [ecological] community.” Until Columbus, Indians were a keystone species in most of the hemisphere. Annually burning undergrowth, clearing and replanting forests, building canals and raising fields, hunting bison and netting salmon, growing maize, manioc, and the Eastern Agriculture Complex, Native Americans had been managing their environment for thousands of years. While they occasionally made mistakes they were able to modify their landscapes in stable, supple, resilient ways. Some areas have been farmed successfully for thousands of years. Even the wholesale transformation, as seen in places like Peru, where irrigated terraces cover huge areas, were exceptionally well done. But all these efforts required close, continual oversight. In the sixteenth century, epidemics removed the boss. American landscapes after 1492 were emptied. Suddenly deregulated, ecosystems shook and sloshed like a cup of tea in an earthquake. Not only did invading endive and rats beset them, but native species too, burst and blasted, freed from constraints by the disappearance of Native Americans. The forest that the first New England colonists thought was primeval and enduring was actually in the midst of a violent change and demographic collapse. So catastrophic and irrevocable were the changes that it is tempting to think that almost nothing survived from the past. This is wrong: landscape and people remain, though greatly altered. And they have lessons to heed, both about the earth on which we all live, and about the mental frames we bring to it.