ECLAC-1998-Progress

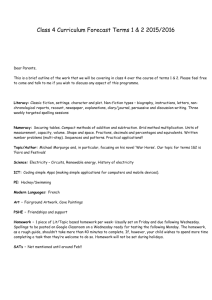

advertisement