CCS- MSS and Effect on Liquidity of INR- Shruti G Vikram B

advertisement

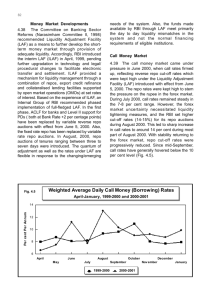

MARKET STABILISATION SCHEME SUBMISSION 3: FINAL REPORT ON AUGUST 27, 2007 BY SHRUTI SUSAN GEORGE (0611047) VIKRAM BALAN (0611201) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT, BANGALORE TERM 4: JUNE-SEPTEMBER 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS SERIAL NO. TITLE PAGE 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2. BACKGROUND OF FII INFLOWS IN INDIA 4 3. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY 4 4. NEED FOR AND METHOD OF STERILISATION 5 5. THE BALANCE SHEET OF THE RBI 6 6. GOVERNMENT DEBT AND CHANGES IN PARAMETERS 7 7. LIQUIDITY ADJUSTMENT FACILITY 10 8. TRENDS IN THE CRR, REPO-RATE AND MSS 12 9. PROBLEMS OF LIQUIDITY OVERHANG 13 10. CONCLUSIONS 16 11. APPENDIX 19 12. REFERENCES 38 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) was introduced in April 2004 to provide the Reserve Bank of India with an additional instrument of liquidity management and to relieve the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) from the burden of sterilisation operations. The MSS is an arrangement between the Government of India and the Reserve Bank to mop up the excess liquidity generated on account of the accretion of the foreign exchange assets of the Bank to neutralize the monetary impact of capital flows. Under the scheme, the Reserve Bank issues treasury bills/dated Government securities by way of auctions and the cost of sterilisation is borne by the Government. The money raised under the MSS is held by the Government in a separate identifiable cash account maintained and operated by the Reserve Bank, which would be appropriated only for the purpose of redemption and/or buyback of issuances under MSS. With credit growth in the economy now showing signs of moderation, the banking system is flush with funds. Increased government spending and RBI intervention in the forex market are also fuelling liquidity in the system. In such a situation, our study looks at determining the effectiveness of the MSS in reining in the money supply in the economy vis-à-vis the other instruments of monetary policy, viz. LAF (repo and reverse repo rates) and the cash reserve ratio (CRR). The methodology we have adopted for our study is an initial data collection of FII inflows, M3 money supply in the economy and inflation rates right from 2004 to the present day. We have tried to associate these with the outstandings under the Market Stabilisation Scheme since its inception in April 2004. We have also studied the points where the ceiling of issuance of MSS bonds has been modified, to understand the reasoning behind that. Further, we have also looked at the trend in the CRR, repo rates and reverse repo rates in the same period to compare their effectiveness as opposed to the MSS. Regression and trend analyses have led us to the few conclusions and recommendations mentioned towards the end. 3 BACKGROUND ON FII INFLOWS IN INDIA Foreign Institutional Investors have been allowed to invest in the Indian market since 1992. The decision to open up the Indian financial market to FII portfolio flows at that point in time was influenced by several factors such as the complete disarray in India’s external finances in 1991 and a disorder in the country’s capital market. Aimed primarily at ensuring non-debt creating capital inflows at a time of an extreme balance of payment crisis and at developing and disciplining the nascent capital market, foreign investment funds were welcomed to the country. FII inflows today are perceived to be major drivers of the stock market in India, and sudden reversals of these flows could lead to instability in the domestic capital market. FIIs can be best described as “fleeting money”, and such a volatile nature of capital flows calls for measures for policy liberalisation and regulatory supervision. The Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) which was introduced in April 2004 is one such measure which provides the Reserve Bank of India an additional instrument of liquidity management. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY The basic objectives of the monetary policy of India are price stability and adequate credit flow to productive sectors of the economy. With significant changes in the operating environment, there is an increasing focus on the maintenance of financial stability in the context of better linkages between various segments of the financial markets. The primary tool of monetary policy is Open Market Operations, which entails management of the quantity of money in circulation through the buying and selling of various credit instruments, foreign currencies and commodities. The Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) is one of the policy initiatives of the RBI in trying to control money supply in the economy. With outsourcing having become a leading employment generator in India, the seemingly endless inflow of dollars into the Indian economy has proved a major challenge to policy makers. The RBI’s ability to resist the pressure of an appreciating rupee on account of this is constrained by the stock of government securities it owns. The Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) was launched with this objective of enhancing capacity to pursue the policy of reserve accumulation without monetary expansion. Also, with increased FII inflows into the 4 country, the net domestic assets and net foreign assets held keep spiraling upwards, leading to an increasing amount of money circulated in the economy. In order to curb the inflationary pressures rising on account of this, the Reserve Bank initiated a process to reduce its holdings of net domestic assets by selling bonds and taking away liquidity from the market. This process is called “sterilisation” and forms the essence of the Market Stabilisation Scheme. With this background, we lay down the basic objectives of our study: To understand the various instances in which the RBI employed the MSS as a tool to control the money supply. To trace the reasons behind the hiking of the ceiling for the scheme and analyse the MSS from a fiscal as well as monetary viewpoint. To analyse the effectiveness of MSS vis-à-vis the other open market operations like the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) used by the RBI, and the impact that it has produced over the last 2 years since its implementation. To analyse implementation of the MSS and suggest alternatives and modifications to the present strategy of reducing liquidity. NEED FOR AND METHOD OF STERILISATION Say $1 billion comes into the system because some foreign investor wants to invest here. This $1 billion is equivalent to around Rs 4,300 crore and this means that the monetary base has increased by the same amount. An increase in monetary base of such magnitude can trigger inflationary tendencies in the economy. These inflationary pressures would force the Government to further raise interest rates in the economy, which would further attract more capital inflows, resulting in a vicious circle. Sterilisation works at this interface between a) The inflow of capital in the economy b) The increase in overall monetary base The policy of sterilising the inflows is followed when there is a fear of inflation in the domestic economy. The RBI, to neutralize this volatile inflow, issues bonds to suck the Rs 4,300 crore out of the system. In effect, the money supply remains unchanged. However, while sterilisation may thwart inflationary pressures, it is a fairly expensive process since the 5 MSS is one form of government debt, and creates pressures on the RBI balance sheet due to interest outflow on this debt. Sterilisation is equivalent to two operations by the RBI: first, it purchases the gift with money creation, and then it absorbs the newly created money through the sale of government securities it owns. Sterilisation thus affects the composition of the RBI’s balance sheet (i.e., it swaps its domestic assets in the form of government securities for foreign assets of equal value). Government securities are liabilities of the government regardless of whether they are held by RBI or others to whom RBI sells them. As such, in a consolidated balance sheet of the government and RBI, liabilities are unaffected by the swap, and the asset side is larger by the amount of the foreign gift. If the RBI did not sterilize its newly created money, its non-interest bearing currency liabilities would go up by the value of foreign gift it buys. In a consolidation, non-interest bearing liabilities and assets go up by the same amount. THE BALANCE SHEET OF THE RBI Most central banks act as managers of public debt for a commission. Central banks often maintain a high ratio of net foreign assets to currency to ensure the wherewithal to meet any domestic demand for foreign currency. These banks conduct monetary operations through a mix of instruments, such as, open market operations (and occasionally, changes in reserve requirements and standing facilities), which adjust the quantum of primary liquidity and changes in policy rates, which impact the price of base money. There now appears to be an emerging consensus that central bank reserves act as a cushion in the sense that wellcapitalised central banks are relatively more credible in a market economy because they can bear larger quasi-fiscal costs of market stabilisation, especially in case of large fiscal deficits. Changes in reserve requirements alter the composition and profitability of the Reserve Bank Balance Sheet (and reserve money) as well as bank liquidity. A change in the cash reserve ratio (CRR) alters the ratio of currency and reserves on the liability side. The impact on the asset side depends on the particular monetary environment. For example, if the CRR is raised to sterilise the impact of capital inflows, there would be a shift in favour of foreign assets. Second, if the CRR is raised in order to tighten monetary conditions to stem capital outflows, the market liquidity gap generated by the mix of higher reserve requirements and 6 drawdown of foreign currency assets is likely to be funded by an increase in domestic assets either through reverse repos or higher recourse to standing facilities. Finally, a reduction in the CRR is almost always associated with a reduction in domestic assets as banks either invest the release of resources in repos or redeem standing facilities. The payout in the form of CRR balances is a charge on income. GOVERNMENT DEBT AND CHANGES IN PARAMETERS The following data have been obtained from the debt position of the Government of India, and show the internal and external debt of the government. As mentioned earlier, the liabilities under the Market Stabilisation Scheme are included as a separate entry in the balance sheet, and the same is shown under: Figure 1: Debt position of the Government of India Using the above, we have plotted a variation of the government debt versus time, and compared it with the variation of debt due to MSS versus time. From this graph, we can see that the fiscal debt accrued through MSS has grown at a faster rate and has faced larger volatility than the net fiscal debt. While the net fiscal debt increased by 14.5% over the financial year 2005-06 to 2006-07, the debt due to MSS issuances increased by 150%. But the 7 trend to be observed is that the MSS is now being decreasingly used as an instrument to absorb liquidity as can be seen from the next graph, where the LAF outstanding and the MSS outstanding are plotted against time. Government Debt 3000000 20000 2500000 40000 2000000 60000 1500000 80000 1000000 100000 120000 500000 0 0 31st March 2003 31st March 2004 Debt due to MSS 31st March 2005 31st March 2006 31st March 2007 Overall internal debt Figure 2: Overall and MSS debt over time The Reserve Bank cannot pay interest on Government balances or on bank balances, in excess of CRR stipulations. Since the Government cannot receive interest on surplus balances with the Reserve Bank, it typically “buys back” Government paper from the central bank (up to Rs.10,000 crore) for the period of surplus and saves the interest payment. This means if capital flows do not follow the seasonality of the Government expenditure and the Centre runs a surplus, the Reserve Bank needs to have a sufficient stock of Government paper to transfer to the Government. This is how the Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) was recommended. 8 The Government issues paper to mop up liquidity generated by capital flows and parks the proceeds with the Reserve Bank. The monetary impact of the accretion to the Reserve Bank’s foreign assets, arising out of the absorption of surplus capital flows is thus nullified by the decline in the Reserve Bank’s net credit to the Centre, because of the accretion to the Centre’s cash balances with the Reserve Bank. Although it is money-neutral, the MSS enlarges the Reserve Bank Balance Sheet because the proceeds are immobilised in a separate identified account within the head of the Centre’s balances with the Reserve Bank, unlike in the case of traditional open market operations which is balance sheet-neutral. While the impact of the MSS on the Reserve Bank’s surplus is limited in terms of income, the central bank’s rate of surplus declines because the consequent increase in the size of the balance sheet requires higher allocations to be made in terms of Contingency Reserves. Historically, the CRR hikes have been far more successful in driving increases in borrowing and lending rates by banks than increases in signal rates like the repo rate. The cost of using the CRR versus the cost of market instruments like the MSS bonds is also an issue. While on the MSS bonds, the government has to bear an interest charge of anywhere between 7.5 and 8 per cent, depending on the tenor, the RBI shells out a meager 0.5 – 1% on CRR balances. As a result, The RBI now has increasingly started using CRR as a tool to sterilize liquidity from the market. Use of CRR has two advantages to the RBI: It sends out a strong signal that the Central Bank intends to pursue a tight monetary policy and second sterilisation cost through CRR is almost negligible compared to the other instruments. Current effective interest rate paid on CRR balances stands at 1% (reduced to 0.5% from FY08), while the interest paid on a LAF operations is 6% (no change in rates in the latest announcement) and around 7.5-8% on the MSS bonds depending on tenure whether it is a treasury bill or dated security. This way the government is saving around 5.5-7% on the cost of liquidity sterilisation. CRR hike compresses Net interest Margin (NIM) further adding to RBI’s objective. 9 LIQUIDITY ADJUSTMENT FACILITY Another open market operation that the RBI undertakes to constrain liquidity is the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF). The LAF is a tool used in monetary policy that allows banks to borrow money through repurchase agreements. This arrangement allows banks to respond to liquidity pressures and is used by governments again to assure basic stability in the financial markets. Liquidity adjustment facilities are used to aid banks in resolving any short-term cash shortages during periods of economic instability or from any other form of stress caused by forces beyond their control. Various banks will use eligible securities as collateral through a repo agreement and will use the funds to alleviate their short-term requirements, thus remaining stable. Repo rate is the rate at which the central bank lends money to the other banks. The reverse repo rate is the rate at which the other banks park their excess funds with the central bank. The reverse repo rate is always lower than the repo rate and is generally equal to the lending rate between banks (excluding the central bank). The word repo represents the collateral that is given by banks to the central bank for borrowing money. On repayment of the borrowing the banks repossess their collateral given to the central bank, hence the word repo rate. An increase in the repo rate reduces the money supply in the system whereas a decrease in the repo rate infuses money into the system. An official hike in fixed reverse repo rate signals that the RBI wants to tighten liquidity in the market believing that it will help in controlling the expected inflation. The monetary management of the sustained capital flows since November 2000 poses a challenge, especially as the Reserve Bank is beginning to run out of government paper for countervailing open market operations. The choice between the three standard solutions, Raising reserve requirements Issuing central bank securities Conducting uncollateralised repo operations, (assuming the central bank is credible enough) is often critical, especially as the degree of market orientation and the associated incidence of the deadweight loss of sterilisation on the monetary authority and the banking system varies a great deal. An intermediate solution between central bank bills (which concentrate the cost 10 on the former) and reserve requirements (which impose a tax on the latter) is to conduct a continuum of relatively short-term uncollateralised repo operations. While the Market Stabilisation Scheme provides the Reserve Bank the headroom for maneuver, the proposal of the Reserve Bank's Internal Group on Liquidity Adjustment Facility to amend the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 in order to enable the institution of a standing deposit-type facility merits attention. Few experts believe that the RBI should not use CRR as an instrument of sterilisation. Open market operations/MSS should be used instead. They are of the opinion that when the CRR is raised, banks have to go out and borrow more, usually by way of high-cost deposits; or sell off any holdings of government bonds in excess of the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) requirement; or, call in loans. No one expects banks to call in loans. Efficient banks, unlike “lazy banks”, do not have surplus holdings of government bonds, and are thus forced to take high-cost deposits. This has to be done whenever the central bank hikes CRR. In contrast, open market operations through the MSS allow the RBI to sterilise its intervention as and when it occurs. Buying government bonds beyond the SLR limit is optional, and hence higher rates have to be offered to attract banks to buy them, which spells higher interest rates overall. The net effect, however, is a more efficient and smooth system. 11 TRENDS IN THE CRR, REPO-RATE & MSS MSS, CRR, Repo Rate vs Time 12000 12 % 10000 10 % 8000 8% 6000 6% 4000 4% 2000 2% 0% 0 FY 02 MSS CRR Repo rate Reverse Repo FY 06 Figure 4: Movements of the instruments of monetary policy with time From this graph, we can see that the LAF interest rates (CRR, repo and reverse repo) are being changed around once every quarter after a period from FY 2003 to FY 2005 when it was kept constant and MSS was being used as a liquidity absorption instrument. . During the fiscal year 2005-06, the total issuances of MSS bonds decreased from 87,500 crore rupees to 50,000 crore rupees and then increased in the next financial year to 96,000 crore rupees. (See Appendix) Simultaneously, the RBI raised repo and reverse repo rates were raised around 200 basis points, with the spread increasing from 100 basis points to 175 basis points. The RBI thus has been shifting its focus from exclusive use of the MSS (as in 2004-05) to using all the instruments for reducing liquidity. 12 PROBLEMS OF LIQUIDITY OVERHANG Liquidity overhang is the excess funds in the system that is not being used for consumption or investment purposes. It is idling money. Inflation control is often cited as a reason for creating liquidity. It is argued that releasing large sums of money into the economy would immediately drive prices up. The financial reality of reducing the liquidity overhang is quite different. Releasing such large sums of money into the economy as investments can raise productivity. Investment in the latest knowledge-embodied technologies is only going to raise efficiency and lower real costs. However, the Indian economy still does not seem to be producing development schemes worthy of funding at the rates at which the liquidity in the economy is going up. Some of the sources of liquidity in the economy are: The Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) The Market Stabilisation Scheme (MSS) Surplus funds with the Life Insurance Corporation of India Excess funds with commercial banks 13 Figure 5: LAF and MSS outstanding values from 2004 to 2007 14 The graphs of LAF and MSS below show that the RBI is balancing the outstanding LAF bonds and MSS bonds outstanding issued by a mix of changes in repo and reverse repo rates and actively selling bonds. From the financial year 2006-07, the outstanding LAF debts have been negative. The RBI is thus a net creditor of the external banks and has pumped liquidity into the system. This has been counterbalanced by increasing amounts of MSS issuances. LAF & MSS Outstanding 100000 80000 60000 40000 20000 0 -20000 -40000 FY04 FY05 FY06 LAF FY07 MSS Figure 3: LAF and MSS outstanding over a period of time Thus, while the MSS provided another tool for liquidity management, it was designed in such a manner that it did not have any fiscal impact except to the extent of interest payment on the outstanding amount under the MSS. The amount absorbed under the MSS, which had reached Rs.78,906 crore on September 2, 2005, declined to about Rs.32,000 crore in February 2006 due to unwinding of nearly Rs.47,000 crore in view of overall marginal liquidity which has transited from the surplus to the deficit mode. As part of unwinding, fresh issuances under the MSS were suspended between November 2005 and April 2006. In several subsequent auctions during 2006-07, only partial amounts were accepted under the MSS. Subsequently, the amount absorbed under the MSS increased again to Rs.62,974 crore in March 2007. The MSS has, thus, provided the Reserve Bank the necessary flexibility to 15 not only absorb liquidity but also to ease liquidity through its unwinding, if necessary. With the introduction of the MSS, the pressure of sterilisation on LAF has declined considerably and LAF operations have been able to fine-tune liquidity on a daily basis more effectively. Thus, the MSS empowered the Reserve Bank to undertake liquidity absorptions on a more enduring but still temporary basis and succeeded in restoring LAF to its intended function of daily liquidity management. CONCLUSIONS The Appendix shows that FII inflows into the country, over the last few years, grew tremendously from a meager Rs. 2900 crore to Rs. 48,335 crore. This necessitated the setting up of additional instruments for control of money supply in the economy, and hence we see that the Market Stabilisation Scheme was setup as a policy tool since April 2004. We can see that the average quarterly inflation rate has reached a high of 7.8% in the months of July-August 2004, and in the same period we see a big jump in the rate of FII inflows, which is quite an expected sign. Again, in the 4th quarter of 2005-06, the inflation reached a low of 4.0%, and quite obviously, curbing price rise would not have been high on the agenda of the RBI. As a result, we see that even though the FII inflows went up from Rs. 6696 crore to Rs. 16089 crore, the bonds issued under the Market Stabilisation Scheme were zero. However, this led to inflation shooting up to 4.7% by the next quarter. We can see that the outstanding under MSS has been going up ever since its issuance in April 2004, that is, from Rs. 14296 crore to the present-day value of Rs. 98970 crore. Further, the yields on the 91-day and 364-day bonds issued under the MSS have also gone up from around 4.3-4.4% in April 2004-05 to the present-day value of 7.4-7.6%. Hence we can conclude that the public debt of the Government of India has gone up tremendously on account of MSS alone. The result of the above is the mounting pressure on the fiscal debt for the government. 16 The Appendix also gives us the trend in the M3 money supply in the country, and shows the increase in every quarter and every year. From the details, we can clearly see that liquidity in the system has been going up by huge proportions every year. Also, from 2005-06 to 200607, it is evident that even though the bonds issued under the MSS were increased from a value of Rs. 50000 crore to Rs. 96000 crore, the increase in liquidity in the system has been Rs. 567,372 crore as opposed to Rs. 458,456 crore the previous year. There was a release of net liquidity of the order of Rs.5500 crore in the second half of November 2005 through MSS redemptions as the Reserve Bank refrained from fresh auctions under the scheme in the second half of the month. During this period, the liquidity in the system had tightened and fresh issuances of MSS bonds were suspended. The reverse repo rate then was increased from 5.00% to 5.25% and then 5.50% and it was accompanied by a simultaneous redemption of MSS bonds to inject liquidity into the system. Infact this period witnessed massive redemption of MSS bonds thereby reducing the total MSS outstanding from Rs. 70000 crore in the 2nd quarter of 2005-06 to about Rs. 30000 crore by the end of that financial year. The correlation between M3 money supply, FII inflows in the debt and equity markets and inflation to the CRR, MSS issuances, repo rates and reverse repo rates were found with the help of SPSS. From the different lags applied to the dependent variable (1-3 months and 1-3 quarters), it was found that M3 money supply showed the most significant correlation to repo rates and reverse repo rates at no lag, and to CRR at one quarter lag. Similarly, inflation showed a positive correlation at 2-quarters’ lag to reverse repo rates. MSS did not show significant correlation to any dependent variable using quarterly data. Using monthly data, it was seen that MSS showed a positive correlation with inflation, which is contrary to what should be seen. This implies that MSS shows a short term positive effect on liquidity and must be examined in greater details for anomalies. Regressions were carried out using quarterly data and it was seen that none of the variables was able to satisfactorily explain the changes in M3 money supply quarterly. No significant variables were thus identified. From the Appendices, we can see a clear trend wherein the M3 broad money supply in the economy and the interest rate instruments (CRR, repo rate and reverse repo rates) show a 17 positive correlation. This tells us that with an increase in the M3 money supply, the government resorts to an increase in one or all of these 3 instruments to suppress the liquidity. However, a relation between the application of these instruments including the Market Stabilisation Scheme and inflation rates in the economy is not evident. This could be probably because a lot more factors work towards influencing inflation rates in the economy – exchange rates, currency markets, etc. An assumption we state here is that of causality, by which we say that the correlations talk about the application of the monetary policy instruments as dependents on the broad money supply (M3), while the inflation rates are a dependent on these instruments. 18 APPENDIX [1] Regression with lag: b Va riables Entere d/Re moved Model 1 Variables Entered Repo, a MSS, CRR Variables Removed . Method Enter a. All reques ted variables ent ered. b. Dependent Variable: M3 Model Summary Model 1 R .718a R Square .516 Adjusted R Square .355 Std. Error of the Estimate 54532.08016 a. Predictors: (Constant), Repo, MSS, CRR ANOVAb Model 1 Regres sion Residual Total Sum of Squares 2.9E+010 2.7E+010 5.5E+010 df 3 9 12 Mean Square 9519712885 2973747767 F 3.201 Sig. .076a a. Predic tors: (Constant), Repo, MSS, CRR b. Dependent Variable: M3 Coefficientsa Model 1 (Constant) MSS CRR Repo Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error -238611 178090.3 -3.742 2.113 -37578.9 57309.890 93134.267 42191.858 Standardized Coefficients Beta -.432 -.256 .879 t -1.340 -1.771 -.656 2.207 Sig. .213 .110 .528 .055 a. Dependent Variable: M3 19 [2] Regression with 1-Q lag: b Va riables Entere d/Re moved Model 1 Variables Entered Repo, a MSS, CRR Variables Removed . Method Enter a. All reques ted variables ent ered. b. Dependent Variable: M3 Model Summary Model 1 R .653a R Square .426 Adjusted R Square .211 Std. Error of the Estimate 62815.65393 a. Predictors: (Constant), Repo, MSS, CRR ANOVAb Model 1 Regres sion Residual Total Sum of Squares 2.3E+010 3.2E+010 5.5E+010 df 3 8 11 Mean Square 7811312463 3945806379 F 1.980 Sig. .196a a. Predic tors: (Constant), Repo, MSS, CRR b. Dependent Variable: M3 20 [3] Regression with 2-Q lag: Variables Entered/Removedb Model 1 Variables Entered Variables Removed RRepo, MSS, aCRR, Repo Method . Enter a. All requested variables entered. b. Dependent Variable: M3 Model Summary Model 1 R .777a R Square .604 Adjusted R Square .340 Std. Error of the Estimate 47732.69146 a. Predictors: (Constant), RRepo, MSS, CRR, Repo ANOVAb Model 1 Regres sion Residual Total Sum of Squares 2.1E+010 1.4E+010 3.5E+010 df 4 6 10 Mean Square 5208132860 2278409834 F 2.286 Sig. .175a a. Predic tors: (Constant), RRepo, MSS, CRR, Repo b. Dependent Variable: M3 Coefficientsa Model 1 (Constant) MSS CRR Repo RRepo Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error -327494 211440.7 3.136 1.983 21864.191 62472.424 -108246 98639.426 177801.8 99192.370 Standardized Coefficients Beta .449 .163 -1.208 1.554 t -1.549 1.581 .350 -1.097 1.792 Sig. .172 .165 .738 .315 .123 a. Dependent Variable: M3 21 [4] Correlations without lag: Descriptive Statistics Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Mean 5.4177 107111.8 9916.3800 19461.54 5.0192 6.5192 5.2885 Std. Deviation 1.07979 67898.74112 7708.65848 7843.41958 .46167 .64114 .58493 N 13 13 13 13 13 13 13 Correlations Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Inflation 1 13 -.200 .256 13 -.028 .464 13 .550* .026 13 -.346 .123 13 -.060 .423 13 -.340 .128 13 M3 -.200 .256 13 1 13 .199 .257 13 -.254 .201 13 .430 .071 13 .587* .017 13 .626* .011 13 FII -.028 .464 13 .199 .257 13 1 13 -.273 .183 13 .300 .160 13 .213 .243 13 .178 .281 13 MSS .550* .026 13 -.254 .201 13 -.273 .183 13 1 13 .023 .470 13 .209 .246 13 .062 .421 13 CRR -.346 .123 13 .430 .071 13 .300 .160 13 .023 .470 13 1 13 .790** .001 13 .711** .003 13 Repo -.060 .423 13 .587* .017 13 .213 .243 13 .209 .246 13 .790** .001 13 1 13 .914** .000 13 RRepo -.340 .128 13 .626* .011 13 .178 .281 13 .062 .421 13 .711** .003 13 .914** .000 13 1 13 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed). 22 [5] Correlations with 1-Q lag: Descriptive Statistics Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Mean 5.4358 105674.0 9146.5700 19083.33 5.0625 6.5625 5.3542 Std. Deviation 1.12573 70710.92780 7511.41088 8067.42421 .45383 .64952 .55859 N 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 Correlations Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Inflation 1 12 -.196 .270 12 -.006 .492 12 .350 .133 12 -.079 .404 12 -.122 .352 12 -.403 .097 12 M3 -.196 .270 12 1 12 .184 .283 12 .093 .387 12 .639* .013 12 .579* .024 12 .541* .035 12 FII -.006 .492 12 .184 .283 12 1 12 .066 .419 12 .150 .321 12 -.084 .398 12 -.056 .431 12 MSS .350 .133 12 .093 .387 12 .066 .419 12 1 12 .088 .392 12 .263 .204 12 .147 .325 12 CRR -.079 .404 12 .639* .013 12 .150 .321 12 .088 .392 12 1 12 .776** .002 12 .667** .009 12 Repo -.122 .352 12 .579* .024 12 -.084 .398 12 .263 .204 12 .776** .002 12 1 12 .920** .000 12 RRepo -.403 .097 12 .541* .035 12 -.056 .431 12 .147 .325 12 .667** .009 12 .920** .000 12 1 12 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed). 23 [6] Correlations with 2-Q lag: Descriptive Statistics Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Mean 5.3745 93212.73 9214.3782 18818.18 5.1136 6.6136 5.4318 Std. Deviation 1.15949 58739.24620 7874.18122 8406.16657 .43823 .65540 .51346 N 11 11 11 11 11 11 11 Correlations Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Inflation 1 11 -.400 .111 11 .000 .500 11 .324 .166 11 .020 .477 11 -.405 .108 11 -.648* .015 11 M3 -.400 .111 11 1 11 .257 .223 11 .460 .077 11 .238 .241 11 .508 .055 11 .625* .020 11 FII .000 .500 11 .257 .223 11 1 11 -.070 .419 11 .230 .248 11 -.044 .449 11 .040 .453 11 MSS .324 .166 11 .460 .077 11 -.070 .419 11 1 11 .145 .335 11 .308 .178 11 .231 .247 11 CRR .020 .477 11 .238 .241 11 .230 .248 11 .145 .335 11 1 11 .756** .004 11 .593* .027 11 Repo -.405 .108 11 .508 .055 11 -.044 .449 11 .308 .178 11 .756** .004 11 1 11 .935** .000 11 RRepo -.648* .015 11 .625* .020 11 .040 .453 11 .231 .247 11 .593* .027 11 .935** .000 11 1 11 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed). 24 [7] Regression: Variables Entered/Removedb Model 1 Variables Entered Variables Removed RRepo, MSS, aCRR, Repo Method . Enter a. All requested variables entered. b. Dependent Variable: M3 Model Summary Model 1 R .720a R Square .519 Adjusted R Square .134 Std. Error of the Estimate 57333.95411 a. Predictors: (Constant), RRepo, MSS, CRR, Repo ANOVAb Model 1 Regres sion Residual Total Sum of Squares 1.8E+010 1.6E+010 3.4E+010 df 4 5 9 Mean Square 4432355755 3287182294 F 1.348 Sig. .369a t Sig. .560 .609 .209 .221 .376 a. Predic tors: (Constant), RRepo, MSS, CRR, Repo b. Dependent Variable: M3 Coefficientsa Model 1 (Constant) MSS CRR Repo RRepo Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error 284130.5 455219.4 -1.391 2.549 -175763 121996.9 272419.7 194795.1 -195479 201246.4 Standardized Coefficients Beta -.200 -1.167 2.904 -1.542 .624 -.546 -1.441 1.398 -.971 a. Dependent Variable: M3 25 [8] Correlations 3-Q lag: Descriptive Statistics Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Mean 5.3360 91460.70 9161.1600 18950.00 5.1750 6.6750 5.5000 Std. Deviation 1.21475 61612.89051 8298.03028 8848.88568 .40910 .65670 .48591 N 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Correlations Inflation M3 FII MSS CRR Repo RRepo Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Inflation 1 10 -.416 .116 10 -.003 .497 10 -.031 .466 10 -.112 .379 10 -.648* .021 10 -.759** .005 10 M3 -.416 .116 10 1 10 .256 .237 10 .175 .314 10 .161 .329 10 .552* .049 10 .558* .047 10 FII -.003 .497 10 .256 .237 10 1 10 -.240 .252 10 -.033 .464 10 -.098 .394 10 -.018 .480 10 MSS -.031 .466 10 .175 .314 10 -.240 .252 10 1 10 .137 .353 10 .308 .194 10 .233 .259 10 CRR -.112 .379 10 .161 .329 10 -.033 .464 10 .137 .353 10 1 10 .726** .009 10 .489 .076 10 Repo -.648* .021 10 .552* .049 10 -.098 .394 10 .308 .194 10 .726** .009 10 1 10 .936** .000 10 RRepo -.759** .005 10 .558* .047 10 -.018 .480 10 .233 .259 10 .489 .076 10 .936** .000 10 1 10 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed). [6] Basic data [7] 91-day bond issuance under MSS [8] 364-day bond issuance under MSS 26 REFERENCES [1] Reserve Bank of India. Report on Currency and Finance 2003-04, 2004-05, 2005-06 [2] Reserve Bank of India. Annual Policy Statement for the year 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07 [3] Debt Position of the Government of India, Government Receipts Budget 2004-07. [4] Kumar, Saji. FIIs vs Sensex – An Emerging Paradigm, 2006. [5] http://www.rbi.org.in [6] http://www.epw.org.in [7] http://www.econstats.com [8] http://www.indiastat.com [9] http://indiabudget.nic.in 27