AC02825T04 - OAS :: Department of Conferences and

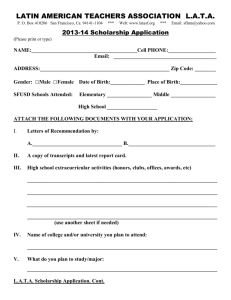

advertisement