Financial Fragility in Japan: A Governance Issue*

advertisement

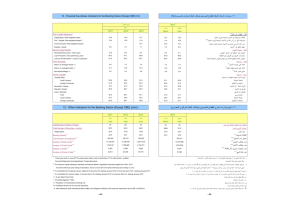

A Bank Crisis in a Bank-Centered Financial System - The Japanese Experience since the 1990s - October 2002 Akiyoshi Horiuchi ** (University of Tokyo) Abstract Relationship banking makes banks’ loan assets opaque to outsiders. The opaqueness of loan assets accounts for the delayed process of disposing non-performing loans by obscuring the critical situation of the Japanese banking sector since the early 1990s. We have observed that capital market mechanism cannot develop so promptly as to compensate for degeneration of relationship banking. Then, should we hurry to dispose of non-performing loans? Only if the quick disposition will lead to a quick reconstruction of relationship banking, the answer to this question is “yes.” This is a revised version of the paper presented at the International Financial Symposium Overcoming Financial Crisis: Financial Reform in Asia organized by the Korean Deposit Insurance Corporation and Asia Pacific Economic Association held on October 25 th , 2002 in Seoul. The author acknowledges helpful comments given by Yung Chul Park, Yoon Je Cho, and Ralph Byun on the original version of this paper ** E-mail address: horiuchi@e.u-tokyo.ac.jp Introduction Japan has suffered from the ill-effects of a long-lasting bank crisis that began in the early 1990s. Table 1 summarizes the data regarding non-performing loans of Japanese depository institutions (i.e., the banks and the cooperative financial institutions) since March 1998, when they first began to disclose figures based on comprehensively defined ‘risk management loans.’ The definition of risk management loans is comparable to the definition of non-performing loans adopted by the SEC in the United States. Table 1 shows that during the last few years the amount of non-performing loans has increased to ¥53 trillion, around 10 percent of GDP. The portion of non-performing loans not covered by the reserves for loan losses was 3.7% of the total loans in March 1999, which almost doubled to 7% in March 2002. 1 According to Table 2, which shows the annual number of bank failures, more than 170 depository financial institutions have gone bankrupt since 1992 because of the increasing amount of non-performing loans. Up until the end of fiscal year 2001 (March 2002), the Deposit Insurance Cooperation (DIC) spent more than ¥22 trillion to deal with the failed institutions (Table 3). The government injected almost ¥10 trillion of the public funds into major banks to 1 On May 24, 2002, all of the Japan’s major banks (13 banks) reported the amount of non-performing loans existing at the end of March 2002. According to the reports, the total amount of those banks’ non-performing loans increased to around ¥27.2 trillion on the consolidation bases, which was 47% larger than that observed one year ago. To dispose of the bad loans, the major banks spent more than ¥8.0 trillion, which was more than twice of their current earnings from 1 help strengthen their capital bases in 1998 and 1999. In addition to the injection of public fund, the Japanese government has taken various policy measures in an attempt to resolve this bothersome problem. In particular, the government has expanded the capacity of the Deposit Insurance Corporation (DIC) to promote banks’ disposition of their non-performing loans. At present, the DIC not only financially supports the process of dealing with failed banks, but also purchases loan assets through the Resolution and Collection Corporation (RCC) to help banks restructure their balance sheets. However, Japan has not yet succeeded in regaining financial stability. Even now there exists a great degree of uncertainty as to whether many banks will be able to maintain capital reserves in the face of a continual increase in the amount of bad loans and a decline in the value of bank shareholdings. On September 18 th , in a somewhat astonishing policy announcement, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) announced it would purchase shares from major banks that have suffered capital losses caused by the recent drop in share prices. The unconventional policy adopted by the BOJ symbolizes Japan’s policy makers’ impatience to restore stability to the banking sector. 2 Why has Japan suffered from the non-performing loan problem for such a long time? Why has the Japanese government failed to settle the non-performing businesses. 2 In my view, this BOJ’s policy will have no significant influence on share prices. The aim of the BOJ is reported to criticize the government’s noncommittal attitude toward the banking sector and insisting a drastic policy to force banks to remove the non-performing loans from their balance sheets as soon as possible. 2 loan problem in the banking sector quickly? We can answers this issue from various angles. For example, we should note the fact that the Japanese economy lost growth potential in the early 1990s. Demographic factors, such as a rapidly aging society, could account for some of this loss of growth potential. Also the over-capacity accumulated during the so-called ‘bubble period’ of the 1980s may have depressed the industrial sector’s incentives for new investment. The sharp decline in growth potential may have triggered successive bouts of non-performing loan problem. The government’s policy of forbearance might be responsible for the persistence of the banking crisis. This paper investigates this issue from the perspective of a theoretical analysis of Japan’s financial system. Historically, Japan has depended on a bank-centered financial system where the intimate relationship between banks and their client firms dominates the process of financial inter-mediation and where the capital mechanism plays a relatively unimportant role. Many scholars point out the merits of relationship banking in that it mitigates various difficulties associated with the agency problem stemming from information asymmetries between fund-suppliers (ultimate savors) and fund-raisers (i.e., borrower firms). Fundamentally, relationship banking needs no trading of information about borrowers and keeps the quality of banks’ loan assets mostly undisclosed. This can be a merit because the information is a ‘lemon’ which is difficult to trade. Moreover, some firms prefer relationship banking because they are not required to disclose information which they want to conceal from rival firms. In con trast to relationship banking, the capital market mechanism is based on the market trading of information. However, the trading of information incurs higher cost without an 3 infrastructure built around a reliable auditing system that ensures adequate. The infrastructure is costly to be built up. 3 Thus, it would be impossible to transform the financial system based on the relationship banking to the capital market based system in a short period. The merit of the relationship banking, however, deprives the banking sector of resilience when most banks are suffering with bad loan problems. It is costly for the government to assess the quality of loan assets held by individual banks. The opaqueness of banks’ loan assets hinders the government from timely intervening into bank management. Moreover, the opaqueness of banks’ loan assets obscures the government policy regarding a bank crisis so that people cannot accurately assess whether or not the government policy is appropriate. This paper discusses how those features of the relationship banking have influenced specific processes of disposing of non-performing loans and have hindered quick resolution of Japan’s banking crisis. In the next section, I summarize the theory behind relationship banking in section 2, which stresses the opaqueness of banks’ loan assets peculiar to relationship banking. In section 2, I explain specific developments since Japan ’s banking crisis began in the early 1990s. A key conclusion is relationship banking has influenced Japanese government decision-making regarding the bank crisis. 3 For example, rating agencies are important producers of information about fund-raising firms in the capital market mechanism. It would take a long time to establish a well-functioning rating system in the financial system because the rating information is also a lemon good. Rating agencies need a long time to build up the reputation as reliable sellers of information. 4 Section 3 examines how the Japanese government has been influenced by specific features of relationship banking. Section 4 discusses what we should do at present to deal with the bank crisis based on this paper’s analysis. 2. Relationship Banking: A Theoretical Overview Current economic theory defines the function of banks as a social institution to reduce the agency costs associated with financial inter-mediation occurring under information asymmetries. In particular, banks can closely monitor borrower firms and precisely control the risk of corporate management through long-term relationship with their clients. In Japan banks are allowed to hold shares of their client firms, thereby unifying interests of debt holders and those of equity holders. This financial unification could reduce the agency costs caused by the conflicts of interests between creditors and shareholders (Stiglitz (1985)). It can also enhance banks’ capacity in monitoring client firms. Thus, the essential function of banks can be defined as collecting information and assessing information regarding the client firms (e.g., Diamond (1984), Hellwig (1989) and Rajan (1992, and 1998)). Information processing in relationship banking: Aoki (1994) describes the Japanese traditional ‘main bank system’ as a banks’ monitoring mechanism during the three stages of the loan contract with firms, i.e., at the ex ante stage (examining the firms’ credit worthiness), at the interim stage (watching borrowers’ management in order to prevent their opportunistic behavior), and at the ex post stage (determining the possibility of future recovery of funds from 5 financially distressed borrowers). Japan’s main bank system is a sort of relationship banking where the repeated transactions between banks and firms could be effective in transferring specific information regarding borrowers ’ management. The most conspicuous feature of relationship banking is that it makes information about the borrowers’ management relatively opaque to outside parties. As a result, it is difficult for agents outside the relationship to assess the value of the borrowers’ debt. The opaqueness will be convenient for fund-raising because it prevents dissemination of information firms want to keep from their rivals. More importantly, information is a ‘lemon’ which is traded in the market only with high costs. Relationship banking avoids this costly process by unifying producers and end-users of information in a single unit, i.e., a bank (e.g., Campbell and. Kracaw (1980)). Needless to say, relationship banking is not unique to the Japanese financial system. We observe similar (sometimes stronger) relationship between major banks and major companies in Germany called as the ‘Hausbanken’ (Edward and Fischer (1994), and Baums (1994)). Even in the United States the relationship banking has played an important role particularly in financing small and medium size businesses (Pertersen and Rajan (1995), Kroszner and Strahan (1999), and Bodenhorn (2001)). The function of a financial system based on the capital market forms a sharp contrast to that of relationship banking. The financial system based on the capital market fundamentally depends on information traded through open markets and on reliable rules of disclosure. Market prices of individual firms’ debt and equity 6 are supposed to reflect the information regarding the quality of the firms ’ management. Compared with relationship banking, the open capital market disseminates the relevant information of the fund-raising firms, and thereby makes it easier for investors in general to assess the quality of debt and equity issued by the firms. 4 Relationship banking is based on a bilateral monopolistic transaction between the bank and its borrower firms. The long-term relationship with a specific firm helps the bank to monopolize information on the firm. The banks could take the future business opportunities of the firm into account when they determine loan pricing (Sharpe (1990), and Rajan (1992)). Furthermore, the banks play a particularly important role when the borrower firms fall into financial distress. Since nobody has information of the quality comparable to that possessed by the relationship bank (‘the main bank’ in Japan), the bank is almost inevitably involved in dealing with firms that fall into financial distress. Theoretically, the bank should rescue firms by extending additional credit when the possibility of their recovery is estimated to be sufficiently high. But when the firms are hopeless, the bank should liquidate them in the most efficient way (Rajan (1992)). 5 4 The efficient dissemination of information is so crucial to the capital market-based financial system that misbehavior of essential agents such as auditing companies seriously disturbs the capital markets model. This is what we have observed in the US since last year. 5 In the United States, the legal doctrine of ‘equitable subordination’ makes banks’ stakes of distressed firms subordinate to other creditors’ stakes when the banks make a commitment to rescuing those firms. Thus, this doctrine prevents US banks from being active in rescuing distressed firms. See Prowse (1995). 7 Thus, the pricing with respect to credit risk in relationship banking is substantially different from that of the open capital market where the estimated default risk of individual borrowers is simply incorporated into the interest rate margins of ‘risk premium.’ The banks must consider the contingency where they will intervene into programs of dealing with their client firms in financial distress. In practice, since the client firms’ debts are not traded in the relationship banking system except for a few large companies, banks cannot depend on the market information to assess client firms’ credit risk. Loan pricing in relationship banking: Because of the banks’ indispensable role in the process of dealing with financially distressed firms, the default risk of borrower firms is not a pure exogenous variable but a controllable one for the bank. In other words, the banks’ attitude and judgment on a specific distressed firm crucially determines whether or not the firm will be able to survive. Since relationship banking prevents dissemination of the relevant information of borrower firms, we cannot obtain any reliable assessment regarding the firms from capital markets. In particular, debts of small and medium size firms are scarcely traded in a bank-centered financial system. Thus, it may be reasonable that the loan pricing in relationship banking does not explicitly incorporate the borrowers ’ credit ratings which are exogenously given by the capital market. Banks treat credit risk in a quite different way in the United States where relationship banking is not prevalent and banks tend to keep ‘arm’s-length relationships’ with their clients. Banks are rarely involved into the process of disposing of distressed firms. Thus, the credit rating of an individual firm is given 8 to banks both by rating agencies and by well-functioning corporate debt markets. The so-called ‘junk bond’ market is helpful in informing market perception of small scale enterprises’ risk to lenders. Bank managers regard the probability of the borrower as being exogenously given, which they can explicitly integrate into the risk-premium they will charge the borrower firm. 6 Some economists are blaming Japanese banks for not explicitly taking credit risk into account and are insisting that banks should impose higher loan interest rates on their clients in order to improve profitability of the loan business. However, as Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) argue, the higher interest rates do not necessarily improve banks’ profitability because the higher interest rates are likely to induce borrowers’ moral hazard behavior. In particular, since banks face serious asymmetries of information associated with non-performing loans, it may be wise for them not to raise loan rates. Limitations of the relationship banking: I have described some features of relationship banking compared with capital market-based financial mechanisms. In short, relationship banking could efficiently mediate between fund suppliers 6 For example, Saunders (2000: pp. 225-38) details how spreads between risk-free discount bonds issued by the government and discount bonds issued by corporat e borrowers of differing quality reflect perceived credit risk exposures of corporate borrowers in the future. Banks would make use of the perceive credit risk when they determine loan-pricing. Recently, Japanese major banks reportedly struggle to follow the similar system of credit risk assessment without significant success. In my view, if the banks really adopt the US style credit risk assessment, it would imply abandonment of relationship banking. I do not think it is good news for 9 and fund raisers while keeping the relevant information about the fund raisers opaque to agents outside the relationship. Most scholars agree that the Japan ’s traditional main bank relationship is a typical case of relationship banking (Aoki and Patrick (1994)). Did the Japan’s relationship banking system enhance the efficiency of financial inter-mediation? Although this paper will not be able to tackle this issue, I would like to say a few words about it. I would like to say a few words about it. First, we should note that the economic theory predicts a defect of relationship banking. For example, Rajan (1992) shows that the strong bargaining power of banks which monopolize information about their client firms might be a disincentive to bank managers’ effort, and decreasing the social surplus under relationship banking. Second, the mere relationship between banks and firms does not ensure efficient financial inter-mediation. As Aoki (1994) and Prowse (1995) claim, the efficient function of relationship banking requires an effective mechanism to discipline banks to ensure prudent monitoring of client firms. This is the issue of ‘who monitors the monitor.’ In my view, Japan has not succeeded in resolving this important issue in the postwar period (Hanazaki and Horiuchi (2001)). The failure of resolving this issue was at least partially responsible for the fragility of the banking sector, which has been clearly revealed by the huge amount of non-performing loans that have emerged since the early 1990s. Third, all Japanese firms do not prefer relationship banking to the arms ’ Japan’s SMEs. 10 length relationship provided by the capital markets. Some major firms have overcome the informational difficulty as they have established a wide reputati on for good fund-raisers. To those firms relationship banking is no longer indispensable. They can use various financial services supplied by international capital markets if they want to do so. Actually, the Japan’s major firms belonging to the manufacturing industries have substantially reduced their dependence on bank borrowing since the late 1970s (Hanazaki and Horiuchi (2000)). In contrast with this, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and newly born firms strongly need relationship banking in order to reduce the agency costs. Thus, in Japan, the relationship banking is important mainly for SMEs (Petersen and Rajan (1995)). During the period from the 1980s to the early 1990s, the Japan’s financial system based on relationship banking was highly admired for its efficiency in stimulating the postwar industrial development (e.g., Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein (1991), and Aoki and Patrick (1994)). I think the admiration went too far (Hanazaki and Horiuchi (2000)). However, after the banking crisis su rfaced during the 1990s, many scholars have argued for drastic policy measures that are likely to endanger viability of relationship banking in Japan. I think those arguments go too far as well. The following sections will explain why I think so. 3. Disposition of Bad Loans in Relationship Banking The previous section stressed that relationship banking tends to keep the information regarding borrower firms opaque to outside parties. This opaqueness 11 of banks’ loan assets prevents the financial authority, i.e., the MOF until the late 1990s and the Financial Services Agency (FSA) thereafter, from precisely assessing individual bank soundness. Moreover, it gives banks and the FSA substantial room to manipulate disclosed figures of non-performing loans. This possibility of manipulation has been the basis of the government ’s policy of forbearance. Bank managers, suffering from an increasing amount of the non-performing loans, have incentives to conceal the actual situation. If they honestly recognize the increasing amount of non-performing loans, they are required to put aside loan loss reserves according to the guideline given by the FSA. 7 This decreases the banks’ equity capital and reveals both the fragility of the banks and their managers’ incompetence. A decrease in the capital adequacy ratio might trigger off intervention of the FSA into banks’ management following the prompt corrective action (PCA) rule that came into operation in April 1998. This rule requires the FSA to order banks to restructure or to stop their business when the capital adequacy ratios of the banks fall below prescribed levels. Thus, it is understandable that banks would try to underrate the amount of their non-performing loans as much as possible. In order to force the banks to quic kly 7 The FSA’s guideline requires banks to classify their loan assets into the following five categories: (1) sound assets, (2) the assets to be carefully treated, e.g., the claims to the firms recording negative profits, (3)the assets to be treated with high caution, e.g., the claims to the firms that delay interest payment longer than three months, (4) the claims to the firms that are highly likely to default, e.g., those being in excess of liabilities over their assets, and (5) the claims to the virtually or actually bankrupted borrowers. The guideline prescribes the ratios of loan loss reserves for the respective categories of assets. Table 3 presents the 12 dispose of non-performing loans, the FSA should prevent this underrating by means of rigorous inspections. However, it is extremely costly even for the FSA to uncover manipulation on the part of banks due to the opaqueness of their loan portfolio. Moreover, we should note that to force banks to severely assess their loan assets does not necessarily produce good results. The severe assessment of loan assets is likely to lead the banks to abandon helping firms in distress but with good potential. Severe inspection practice by the FSA may wipe out the merit of relationship banking. Although many people loudly insist that the FSA should make severe inspections on banks, in my view, it takes very subtle skills to determine what the optimal level of severity in assessing banks’ loan assets is. As I will discuss in detail below, the Japanese government had a motive to be soft on the banks’ self assessment of loan assets. Most Japanese people sensed the existence of implicit collusion between banks and the FSA to underrate the amount of the non-performing loans. They were skeptical about the disclosed non-performing loans. But they were unable to verify that FSA’s shirking from rigorously supervising banks’ management because they have no access to the relevant information regarding banks’ loan assets either. The criticism against the FSA’s soft attitude towards bank management did not effectively prevent this defect. Why is the BIS capital adequacy ratio unreliable in Japan?: The opaqueness prescribed loan loss reserve ratios. 13 of quality of banks’ loan assets makes the BIS capital adequacy ratio unreliable as a policy target in Japan. As I have already pointed out, the opaqueness gives bank managers some room for manipulating accounting figures regarding their own capital. The banks are induced to underrate the non-performing loans in order to conceal substantial declines in their capital adequacy ratios. It is difficult for outsiders to precisely assess the actual state of individual banks’ capital adequacy ratios. We have observed some cases where banks continued to show sufficiently high levels of BIS capital adequacy ratios just before they abruptly went bankrupt. For example, at the end of March 1997, the Hokkaido-Takushoku Bank’s disclosed BIS capital adequacy ratio was 9.34%. That ratio was the highest of the capital adequacy ratios of all the city banks’ existing at that time. But Hokkaido-Takushoku all too soon went bankrupt in October 1997. The BIS capital adequacy ratio of Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan, which went bankrupt in October 1998 and was thereafter temporarily nationalized, was 10.36% at the end of March 1998 – sufficiently higher than the 8% level required of banks that operate internationally. The Nippon Credit Bank’s disclosed BIS capital adequacy ratio was 8.25% at the end of March 1998 and 8.19% at the end of September 1998 respectively. But the bank failed in December 1998 with large excess liability. Nobody could have anticipated those banks’ failure by only watching their disclosed capital adequacy ratios. Generally speaking, with the opaque nature of relationship banking, BIS capital adequacy ratio and any other accounting figures that are utilized as a measure of bank soundness are not as reliable as policy makers might expect. This 14 is unfortunate particularly because the government started a rule of prompt corrective actions (PCA) based on the official figures of BIS capital adequacy ratios in April 1998. Specifically, when a bank’s BIS capital adequacy ratios fall below 8%, the FSA will automatically intervene into the banks’ management affairs with a view to prevent the banks’ excess liability from growing too large. But if the BIS capital ratio is unreliable, the PCA rule is a blunt instrument. Table 4 shows to what extent failed banks were found to underrate t heir non-performing loans immediately before their failure. The table deals only with bank failures after the introduction of the PCA rule, which formally gives the FSA strong authority to supervise bank management. According to this table, the FSA’s assessment of the failed banks’ non-performing loans was greater than the banks’ self assessment by 40% on average, suggesting underrating of non-performing loans by banks. Even after the start of the PCA rule, the FSA have not succeed in amending the failed banks’ underrating of their non-performing loans. Why were Japanese banks inactive in selling their loan assets? : Loan sales are one of the important methods of banks’ credit risk management (e.g. Saunders (2000: Chapter 27)). If banks, burdened with a large quantity of non-performing loans, could sell their bad loans off, they would be able to liberate resources tied up in tedious and backward-looking projects and redirect them to more positive activities. Thus, the possibility of loan sales would enable banks troubled with non-performing loans to quickly restructure their businesses. By means of loan sales, banks could retain their jobs of originating loan assets while avoiding credit 15 risk. According to a report published by the Bank of Japan (2002), the major banks removed non-performing loans amounting to ¥5.1 trillion from their balance sheets during the year from April 2001 to March 2002. That was around 25% of their non-performing loans and 1.5% of the total loan assets recorded at the end of March 2001. However, only a third of the loan assets that were removed were sales of loan assets to outside agents. Although exact statistics are unavailable, I think that Japanese banks were quite inactive in using loan sale mechanisms to dispose of bad loans until the beginning of the new century. We may say that loan sales by banks have only just started in Japan. An efficient loan sales mechanism requires us to resolve the informational difficulty regarding the quality of bank loans. Outside investors would hesi tate to purchase loan assets originated and sold by banks unless they were confident of their own capacity to assess quality of specific loans. Banks could sell the loan assets they regard as good at ‘appropriate’ prices if outside investors can assess their quality as precisely as the banks themselves. However, as I have stressed, relationship banking has not facilitated the dissemination of relevant information regarding borrowers to outside investors. Even loans asset of high quality would be sold only at deeply discounted prices. It is particularly difficult for banks to inform the quality of non-performing loans to outside investors. This provides a disincentive for banks to pursue loan sales. This is the phenomenon of adverse selection. The difficulty of loan sales has forced banks to continue holding a large amount of bad loans and hindered them from quick restructuring. At a relatively early stage of the no-performing loan crisis (i.e., in 1993), 16 Japan established a semi-public organization, the Cooperative Credit Purchasing Corporation (CCPC), to purchase bad loans from banks. The CCPC operated until March 2001. One purpose of the CCPC was to promote banks’ writing off of bad loans by purchasing the loans at discount prices. Another purpose was for the CCPC to collect debts from borrowers who had defaulted in place of the lender banks. During the seven years from March 1993 to March 2001 the CCPC purchased bad loans amounting to ¥581 billion which was 38% of their book value amounting to ¥1,538 billion and collected the bad loans of ¥465 billion. The divergence of ¥116 between the CCPC’s purchase of ¥581 billion and the loan collections of ¥465 billion was reimbursed by the banks that sold the bad loans to the CCPC. In other words, banks sold the loans to the CCPC with recourse. In this sense, the CCPC was not a device to remove credit risk from banks ’ balance sheets. The RCC’s purchase of bad loans: The government established the Resolution and Collection Corporation (RCC) affiliated to the Deposit Insurance Corporation in April 1999. The legal status of this RCC is the same as a bank. Its major function is to purchase bad loans from both failed and sound banks to promote restructuring of the banking sector. Thus, the RCC was expected to help banks remove bad loans from their balance sheets. But the RCC has not played such an important and significant role as was initially expected. The reason for this disappointed result of the RCC is also related to the informational difficulty associated with relationship banking. The RCC was constrained by law to purchase bank loans at sufficiently low prices to avoid capital losses. Thus, under 17 the information asymmetries, the RCC had to purchase bank loans at extremely low prices. Table 5 presents both the book value and purchase prices of the loans sold by banks to the RCC. This table shows that the purchase prices were on the average only 7% of the loans’ book value. This discouraged banks to sell their loan assets to the RCC. Japan’s traditional relationship banking did not need the open market trading of loan assets originated by banks. Banks were conceived to be able to deal with their client firms in financial distress efficiently while retaining claims to the firms in their own balance sheets (Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein (1990), and Sheard (1994)). In other words, relationship banking was conceived to promote efficient restructuring of financially distressed firms. However, once banks themselves got into financial difficulties, relationship banking was found to be inefficient in coping with the financially distress firms. On the one hand, banks tend to keep more or less hopeless borrower firms alive because if they decide to liquidate those firms it will deplete their own capital adequacy rati os. On the other hand, the retaining of hopeless firms in the loan portfolio crowds out the good firms, particularly small and medium size firms, that have neither established intimate relationship with the banks nor have access to capital markets. Thus, relationship banking in financial distress tends to distort fund allocations in the financial system. That is, the inefficient borrowers continue to be supplied with credit thanks to their long-term relationships with banks while relatively efficient firms or the firms with high potential face rationing of credit. This financial distortion might undermine the long-term growth capability of the Japanese economy. 18 4. The Noncommittal Attitude of the Government In a bank-centered financial system, the relationship between the government and the banking sector profoundly influences how the financial mechanism works. The Ministry of Finance (MOF) used to manage almost all aspects of Japan’s financial system in order to retain the status quo built up during the high growth period after World War II (Hamada and Horiuchi (1987)). The MOF’s principle was to bail out virtually insolvent banks by arranging mergers with a healthy bank. Meanwhile, all of depositors and other investors into banks ’ debt were protected from any burdens associated with the de facto bank failures. 8 This MOF’s policy obscured who were responsible for the troubles and how the cost of the failure was shared by related parties and the general tax payers. Due to the MOF’s active intervention into the process of bailing out default banks, the DIC established in as early as 1971 was useless until 1992 when the DIC operated for the first time to help a regional bank to merge a small mutual bank. However, after the burst of ‘bubble’ in the early 1990s, the MOF was unable to continue the traditional policy of keeping the status quo in the Japanese 8 The MOF belatedly started to burden some debt-holders and shareholders with bankruptcy costs of failed banks around the mid 1990s. When Kosumo, one of the largest credit cooperatives, went bankrupt in July 1995, some financial institutions lending to the credit cooperative were forced to bear some of its bankruptcy costs. When Hyogo Bank and Taiheiyo Bank were reorganized into new banks after their bankruptcy in 1995 and in 1996 respectively, the shareholders’ equity of the old 19 financial system. In particular, the MOF was bitterly criticized for its failure to discipline bank managers for careless risk management. The MOF’s traditional method was abandoned and instead the DIC appeared on the stage. The DIC ’s appearance has contributed to making the cost of bank failures much more transparent. Table 6 shows how the DIC’s financial support became important in coping with bank failures since the mid-1990s. 9 Thus, the government changed the policy framework to deal with bank failures as the bank crisis got more serious in the mid 1990s. However, the government policy continued to be noncommittal in the sense that it required banks to dispose of non-performing loans quickly on the one hand, but also seeks to keep the status quo of the banking sector as much as possible. The ambivalent and noncommittal attitude of the government seems to have hindered a resolution of the non-performing loan problem in Japan. In my view, the government attitude also seems to be a derivative of Japan’s relationship banking. First, the opaqueness of relationship banking allowed the government to hold wishful thinking about the soundness of the banking sector and delayed its recognition of the critical situation. After injecting public funds into major banks, the government became the most important de facto shareholders in those banks. The government is also given strong legal authority over bank management. Therefore, under the current governance structure of bank management, the government is particularly responsible for preventing banks’ manipulation of banks was reduced. 9 Table 7 is a short chronology of the Japanese deposit insurance since the 20 figures relating to non-performing loans. Nevertheless, it was not easy even for the regulators to precisely assess the quality of specific loan assets of individual banks under relationship banking. The informational asymmetry between bank managers and outsiders regarding the value of loan assets hindered the regulators from fulfilling the official role of rigorously monitoring bank soundness. The government could not assess accurately to what extent the bank crisis was deteriorating. 10 Second, in the financial system crucially dependent on relationship banking, the quick disposal of a large amount of non-performing loans is likely to bring forth destructive impacts on the industrial sector. If the government orders banks to dispose of non-performing loans quickly, it will lead to liquidation not only of hopeless firms but also of promising firms which are just temporarily in financial distress. Banks would desire to keep claims to the latter firms in their loan assets. But the opaqueness of the relationship banking will hinder it. The banks hardly succeed in communicating their precise assessment of the borrowers to the regulators. Thus, concerned with destructive effects of quick disposition, the government prefers the banks’ wait and see policy. Of course this concern of the government may be exaggerated. But it should commencement of the DIC at 1971. 10 Being bitterly criticized for a weak attitude toward bank management, the FSA started to be rigorous in inspecting major banks’ non-performing loans in late 2001 through the special inspection. This change in the FSA’s attitude accounts for a substantial increase in the amount of non-performing loans in March 2002. 21 be noted that the fragile banking sector is more destructive to the real economy in a bank-centered financial system than in a financial system with well developed capital markets. In the latter system, efficient capital markets could easily take the place of the banking sector in financial inter-mediation. Thus, the government would be able to take the policy of drastically reorganizing the banking sector without serious concern about its aftermath. 11 The reorganization would substantially reduce the financial capacity of the banking sector at least temporarily. But the government could expect the capital markets to fill the vacancy created by a sharp decline in the banking power. However, it would take a long time to make the transition from a bank-centered financial system to a capital market oriented one. Thus, the opaque nature of relationship banking enhances not only bank managers’ incentives but also the government’s incentive to postpone disposal of non-performing loans. Political pressures on the government: We should also take the political pressures on the government into account when discussing the drawn out process of disposition of non-performing loans in Japan. The government cannot confine its attention to the policy issue of how to deal with the non-performing loan 11 The opaqueness of specific loans implies that the quick disposal of dubious loans might be destructive in the sense that banks are forced to sever a credit relationship with a promising but temporally distressed borrower firm. There may be a trade-off between quickly disposing of banks’ non-performing loans and 22 problem. The Japanese economy has undergone long-lasting stagnation since the burst of ‘financial bubble’ at the beginning of the 1990s. So, the government has needed to take a rather ambivalent stance toward bank management. On the one hand, the government wanted banks to quickly recover their financial stability by disposing of their non-performing loans. To regain financial stability, banks must be conservative enough to strengthen their capital bases and to decrease the amount of non-performing loans. But, on the other hand, the government wants to financially stimulate the Japanese economy. Under a bank-centered financial system, the banking sector has to be active in supplying credit and taking risk in order to stimulate the economic expansion. Obviously these two policy targets are inconsistent with each other. The noncommittal attitude of the government is evident in the injection of public funds into banks. The government purchased preferred stocks issued by some big banks to strengthen their capital. The government gave the financial support to those banks on the condition that they would increase credit supply to small and medium size firms by more than promised percentages. As this policy suggests, the government was concerned not only with the quick recovery of the financial stability of banks, but also with not damaging the banking system so much as to destroy its inter-mediating capability. keeping constructive bank-firm credit relationships. 23 The government’s stealthy measures: The government has taken the policy measures to help bank managers to overcome the difficulty of declining capital bases. These measures obviously contradicted with another policy objective of providing effective disciplines to bank management. For example, the MOF allowed banks to sell subordinate loans to life insurance companies at the start of the BIS capital adequacy rule in the late 1980s. During the first half of the 1990s, the MOF allowed banks to issue subordinate debt in foreign capital markets. This policy induced some Japanese banks to issue a substantial amount of subordinate debt. The main purchasers of the banks’ subordinate bonds were the firms with which the issuing banks had kept long-term relationships. The issuance of subordinate loans and bonds helped Japanese banks to keep their BIS capital adequacy ratios above the prescribed minimum level during the early stages of BIS capital adequacy regulation (Horiuchi and Shimizu (1997)). In March 2000 the government amended the accounting rules to allow banks to book deferred tax assets (DTAs). When banks dispose of non-performing loans, they need to increase the specific reserves that are not tax deductible under the Japanese taxation rules. The accounting rule amendment permits banks to book DTA on the assumption that they will benefit from a lower tax charge when a formal default occurs and the size of the final loss is determined. Banks can record the DTA as part of their shareholders’ equity. Thus, the capital of banks 24 rather abruptly increased due to this accounting reform as of March 2000. 12 Even the recent revision to the Commercial Code, which makes it possible for banks to restructure their businesses using a holding company arrangement, has contributed to mitigating banks’ difficulty of satisfying capital adequacy requirements. The holding company system allows banks to tap into legal reserves to pay dividends. Thus, the banks that adopted holding company structures were able to increase their capacity to pay dividend in spite of negative current profits. This has an important implication for the managers of those banks that accepted public fund as capital injections in the late 1990s. If they could not pay dividends to preferred stocks held by the government, the government would acquire voting rights in the banks, and therefore strengthen its control on bank management vis-à -vis the incumbent managers. Increased capacity of dividend payment is important for bank managers. 12 According to a foreign securities company located in Tokyo, tax deferred assets accounted for more than half of major banks’ capital which was ¥17.3 trillion at March 2002. The policy of allowing banks to record the DTAs is in itself reasonable. However, recording the DTAs is based on the assumption that the banks will earn taxable profits in the future. If they are unlikely to gain positive profits in the near future, it is problematic for the banks to record the DTAs in parallel with disposing of non-performing loans. Some are criticizing banks for overestimating DTAs because the increasing amount of non-performing loans makes it less likely that the banks will be able to earn enough profits to justify the recorded DTAs. 25 Mistaken policy sequences: We should point out the government’s mistakes in the sequence of policies adopted regarding the non-performing loan problem. In this regard, we need to differentiate between two policies. The first is the policy to resolve the current bank crisis and to restore the stability of the financial system. The second one is to re-establish the regulatory framework that will effectively work to prevent excessive risk taking on the part of banks. The first policy is an emergency measure, and the second is the preventive measure, which is necessary after the stability of the banking sector is restored. If th e financial system is confronted with the systemic collapse due to an increasing amount of non-performing loans, we should give priority to emergency policies to rescue the banking sector from the swamp of non-performing loans. 13 After the banking system becomes stable again, we should stringently require banks to behave prudently and should strengthen our capacity of supervising them in order to prevent their excessive risk-taking. If we require some depositors and other investors to share the burden of bank failures by narrowing the scope of the financial safety net, we could expect the capital markets to discipline bank managers (e.g., Calomiris (1999)). Before narrowing the financial safety net, however, we should restore banking system stability. Otherwise, the capital market could exert destructive influence on fragile banks and may, contrary to our intentions, exacerbate the crisis. In short, before 13 Needless to say, this implies neither rescuing every distressed banks nor 26 strengthening prudential regulations, which are preventive measures, we should deploy emergency measures to settle the crisis in the banking system. This is a commonplace principle of the desirable policy sequence. Should we postpone the ‘pay-off’?: However, the Japanese government committed an error not to differentiate the emergency policy measures from the preventive ones. A notable example was the commencement of the so-called ‘pay-off’ of bank deposits in the midst of serious bank crisis in April 2002. The pay-off implies the limited deposit insurance in that the DIC will not protect all the depositors from the failure of their banks. The start of the pay-off has triggered an exodus of a substantial amount of deposits from fragile banks. In the midst of a bank crisis, this is destabilizing rather than stabilizing and adds further confusion to Japan’s financial system. In my opinion, the government should have started the pay-off much earlier, say in the mid-1980s when the Japanese banking system was really stable. Narrowing the safety net in the mid 1980s would have been effective in preventing or mitigating the ‘financial bubble’ caused by an excessive bank credit increase in the latter half of the 1980s. Unfortunately, the Japanese government decided to start the pay-off after the banking sector fell into the mud of non-performing loans. This is clearly an incorrect policy sequence. protecting all depositors from the crisis. 27 In 1998 the government promised to start the ‘pay-off’ in April 2001. But with conservative politicians arguing strongly for postponement of the ‘pay-off’ in late 1999, the government decided to start a limited pay-off in April 2002. That is, the deposit insurance protects time deposits up to the maximum of ¥10 million, but protects all current deposits without limit. The decision to postpone was accompanied with another promise that the full-scale pay-off (i.e., the system of limited deposit insurance protection) would be started in April 2003. Now, another political debate is taking place whether or not the start of the pay-off should be postponed again. 14 Theoretically, as I have argued, starting limited deposit insurance protection in the midst of a bank crisis represents an incorrect policy sequence. So, it should be postponed. However, the repeated policy changes will surely decrease the credibility of government policy and dilute the disciplinary impacts on bank managers that the ‘pay-off’ should eventually be expected to exert. The regulation of banks’ shareholding: Japanese banks are permitted by statute to hold up to 5% of the stocks of their client firms. Under this statute, banks extended the network of mutual shareholdings with their client firms. However, the banks’ shareholdings have become a headachy problem for the Japanese government because the increasing volatility in stock prices has been 14 At the beginning of this month (October 2002), the prime minister Koizumi 28 undermining sound bank management. Thus, in November 2001 the Diet passed a bill that requires banks to keep their holding of stocks under the amounts of tier I capital until September 2004. Obviously, the purpose of the bill is to stabilize the banking system by forcing banks to reduce their stock holdings. However, in my opinion, this is also a mistimed policy because it will force some banks to sell stocks out and thereby exerting a downward pressure on stock prices. I suspect this will not contribute to settling the Japanese bank crisis. 15 5. Concluding Remarks – What Should We Do? This final section discusses the emergency policies for the bank crisis that are now being hotly debated in Japan. The recent decision by the prime minister Jun-ichiro Koizumi to dismiss Hakuo Yanagisawa from the financial matter minister and to appoint Heizo Takenaka as a Yanagiwasa’s successor signals the cabinet’s intention to take more declared that the full-scale pay-off will be postponed once again until April 2005. 15 As I explained at the beginning of this paper, the BOJ announced that it will purchase shares held by major banks and will hold them for a limited time period. Will this BOJ’s policy be effective in sustaining Japan’s stock prices? I do not think so. Investors will rationally take long-term perspectives when they evaluate stock prices. If the BOJ’s temporarily holding of the shares were effective in raising their prices, then investors would expect the stock price falls when the BOJ resell the purchased shares in the future. The investor’s rational expectation will prevent stock prices from significantly rising in spite of the BOJ ’s policy. 29 drastic emergency policy measures to more quickly settle the non-performing loan problem. It is well-known that Mr. Yanagisawa was hesitant to immediately inject the public finds into the bank sector, and Mr. Takenaka has been advocating the emergency policy measures of de facto nationalization of the banking sector. Mr. Takenaka is reportedly planning the policy to force banks, particularly major ones, to reassess their loan assets more stringently, and to increase loan loss reserves in order to clean up bad loans from their balance sheets immediately. This reassessment would substantially deteriorate the banks’ capital bases. In order to continue their business, the banks would have to ask the government another round of capital injections. 16 The policy would increase the government stakes in those banks, approaching to the full-scale nationalization of the Japan’s major banks. Not a few people agree with this Takenaka’s policy plan, because they believe the quick disposal of non-performing loans will force the hopeless borrower firms to exit, and will turn the resources liberated from those exiting borrower to more productive firms and sectors. In the process of reallocation, the banks will be able to recover their capacity to increase credit to promising firms. On October 3, Mr. Takenaka summoned a special project team consisting of five people who are eager for the quick disposal of non-performing loans to 16 We need to reform the present legal framework before directly injecting public funds into the ‘sound’ banks. Under the present legal framework, only after the prime minister declares the ‘financial systemic crisis’ the government will be able to take the policy of financially helping surviving banks to enhance their 30 realize his policy scenario. Quite interesting was the stock market response to this summons of the project team. The stock prices sharply fell. The NIKKEI 225 went down below ¥9,000 for the first time since 1983. Of course, the Takenaka’s policy of quick disposal of non-performing loans would make the business prospects of major banks and the distressed firms worse and, consequently, it would be quite naturally that the stock prices of those banks and firms go down. However, at least according to the Takenaka’s scenario, the other firms’ business prospects should be improved by the quick disposal policy. The stock prices of those firms should go up and canceling out negative influence of stock prices of banks and fragile borrower firms on the average stock price. In reality, however, we have not yet observed significant positive responses of stock market to the Takaenaka ’s policy. In short, the Japan’s capital market does not seem to believe in the scenario advocated by Mr. Takenaka. In my opinion, the sharp divergence between the stock market responses and Mr. Takenaka’s scenario suggests that the Japanese economy has not yet prepared industrial sectors that have high potential to fill the vacancy that the Takenaka’s policy would create by forcing weak firms to exit. Thus, the stock market investors expect that the immediate disposal of non-performing loans would exacerbate the current deflation. Should we take the policy which is capital bases (Article 102 of the Deposit Insurance Law). 31 expected to result in a hard landing? I do not think so. 17 I should also point out that, in the long-term perspective, the nationalization scheme would not be able to solve the most fundamental issue for the Japanese financial system, i.e., the issue of how to develop new business models in the banking and to restructure the system to be more-capital market oriented. The government has no expertise useful to solve this issue. Thus, in my opinion, injecting public funds would be only a policy to gain time. We need to recognize that to solve a bank crisis in a bank-centered financial system is a complicated task. It is particularly so because the bank crisis tend to synchronize with the slowdown of the real economy. 18 In order to stimulate the 17 The FSA is reportedly proposing the policy of enhancing the capacity and role of the RCC in preference to directly injecting public funds into major banks. According to the FSA’s plan, the RCC is going to purchase bad loans from banks at book value. The policy would surely help banks remove their bad loans from their balance sheets and at the same time strengthen their capital bases. This is a plan of implicitly giving financial support to banks without increasing the government’s stakes in the banking sector. Most bank managers would welcome this FSA’s idea, because this policy would preserve the institutional status quo and would not require accountability of the current bank managers. I would myself prefer the scheme of direct injection of public funds to the FSA ’s plan, because the former plan would require accountability of bank managers. 18 At present, most Japanese banks are reluctant to extend credit to SMEs because of their fragile capital bases. As Table 1 shows, the banks are sharply decreasing loan supply. Table 1 shows that for four years from March 1998 to March 2002, the loan supply of ‘All Bank’ decreased by 15% from ¥553 trillion to ¥473 trillion. Instead, they are increasing holdings of government bonds which are regarded as 32 depressive economy, the banking sector needs to actively supply their credit in the bank-centered financial system. In particular, as this paper suggests, they should financially support SMEs through traditional relationship banking. The drastic nationalization scheme would not ensure the effective supply of relationship banking services. So, the emergency policy must take into consideration how it would influence the banks’ loan supply to SMEs. In this regard, the drastic policy of nationalizing major banks would not in itself be constructive. If the major banks retreat from the international banking business, they need not pursue 8% capital adequacy ratios any more, but need to satisfy less stringent ratios of 4% domestic capital adequacy. Then, they will concentrate on business with SMEs without seriously worry about the shortage of capital. What about their clients of large companies? In my view, they have already prepared for transactions in the capital market-based financial system. So, they do not need financial support particularly from relationship banking. The Japanese banks could restructure their business responding to current crisis by utilizing the holding company system. Specifically, the holding company established by a bank divides the banking business that use to be integrated in the bank into a retail banking operated by a regional bank (whose capital adequacy ratio is not 8% but 4%) and an investment banking operated by the small number risk-less assets according to the BIS rule. 33 of officials with excellent expertise of international finance. The business transformation under the holding company system like this will effectively retain the merit of relationship banking in Japan. In sum, I recognize the current critical situation of the Japanese banking sector. It is possible that the government will have to inject the public funds into the banking sector to avoid a full-scale financial systemic crisis in the near future. But the present legal framework has adequately prepared for such a systemic crisis. The scheme of immediate disposal of non-performing loans and the consequent virtual nationalization of major banks would not be particularly constructive as an emergency policy. 34 Table 1: Non-performing loan disclosures (All banks: ¥ trillion) All banks (a) Total amount of risk management loans (b) Specific reserves for loan losses (a) – (b) Total loans March 1998 March 1999 March 2000 March 2001 March 2002 29.76 (5.38) 15.93 (2.88) 13.83 (2.50) 553.13 (100.0) 29.63 (5.85) 11.23 (2.22) 18.40 (3.63) 506.60 (100.0) 30.37 (6.12) 8.46 (1.69) 22.00 (4.43) 496.17 (100.0) 32.52 (6.58) 7.24 (1.47) 25.27 (5.11) 494.19 (100.0) 42.03 (8.88) 7.89 (1.67) 34.14 (7.21) 473.24 (100.0) Cooperative bank (a) Total amount of risk management loans (b) Specific reserves for loan losses (a) – (b) 9.03 11.00 10.93 11.02 (6.66) (8.27) (8.26) (8.28) 3.57 3.13 2.80 2.49 (2.63) (2.35) (2.12) (1.87) 5.46 7.87 8.13 8.53 (4.03) (5.92) (6.15) (6.41) Total loans 135.56 133.04 132.27 133.13 (100.0) (100.0) (100.0) (100.0) (Notes) The risk management loans constitute four categories of bad loans: (1) loans to bankrupted borrowers, (2) past due loans, (3) loans past due more than 3 months, and (4) Restructured loans. 35 Table 2: The number of bankrupted depository institutions a) Banks b) Shinkin banks Credit cooperatives Total 1990 0 0 0 0 1991 1 0 0 1 1992 0 1 0 1 1993 0 1 1 2 1994 1 0 4 5 1995 1 0 5 6 1996 2 3 3 8 1997 5 0 7 12 1998 3 1 31 35 1999 5 6 15 26 2000 1 5 27 33 2001 1 9 37 47 Total 20 26 130 176 Notes: (a) This table contains not only the cases of bank failures dealt with the government, but also those privately disposed. For example, in October 1994, Mitsubishi Bank rescued Nippon Trust Bank at the brink of bankruptcy on its own initiative. The government did not provide any financial support in this case. B ut this table contains it. (b) This column includes city banks, regional I and II banks, trust banks and long-term credit banks. (c) Until November 2001. 36 Table 3: The FSA’s guideline of loan loss reserve ratios for the respective categories of loan assets. Categories of the assets Required reserve ratios (1) Normal assets Around 0.2% (2) The assets to be carefully treated Around 5% (3) The assets to be treated with high Around 15% caution (4) The claims to the firms highly Around 70% probable to go bankrupt (5) The claims to the borrowers 100% virtually or actually bankrupted (Source) FSA 37 Table 4: Disparities of assessment of NPL between failed banks and the FSA (¥ 1.0 billion) Assessment of Assessment of NPLs by the NPLs by the Name of failed Date of the failed banks FSA Divergence banks bank failure (A) (B) (A – B) Kokumin April 1999 149.7 198.2 48.5 (32.4) Kofuku May 1999 428.1 527.5 99.4 (23.2) Tokyo-Sowa June 1999 420.8 690.6 269.8 (64.1) Namihaya Aug. 1999 381.8 556.6 174.8 (45.8) Niigata-Chuo Oct. 1999 234.4 335.3 100.9 (43.0) Ishikawa Dec. 2001 167.3 214.3 47.0 (28.1) Chubu March 2002 78.9 96.5 17.6 (22.3) 1,861.0 2,619.0 758.0 (40.7) Total (Source) FSA and the Japanese Bankers Association (Note) Figures in parentheses present percentages of (A-B)/A. 38 Table 5: The purchase prices and the book value of the loans bought by the RCC Total of purchase Total of the book prices of the loan value of the loans Fiscal year bought by the bought by the (A/B) RCC (billion yen) RCC (billion yen) % (A) (B) 1999 21.7 451.0 4.8 2000 12.6 522.2 2.4 2001 20.6 330.2 6.2 2002* 89.0 690.1 12.9 Total 143.9 1,993.5 7.2 (Note) * Until the second quarter of 2002 fiscal year (Source) Deposit Insurance Corporation 39 Table 6 : The financial support given by the Deposit Insurance Corporation (¥1.0 billion) The ] number of Purchase of Loans and Fiscal year cases Grants bad loans others Total ~1995 9 709 0 8 717 1996 6 1,316 90 0 1,406 1997 7 152 239 4 395 1998 30 2,685 2,682 0 5,366 1999 20 4,637 1,304 0 5,941 2000 20 5,191 850 0 6,041 2001 54 2,069 503 0 2,571 Total 146 16,758 5,668 12 22,438 (Source) Deposit Insurance Corporation 40 Table 7: A short chronology of the Japanese deposit insurance 1971 Deposit Insurance Corporation (DIC) was established. The insurance coverage was limited to ¥3.0 million. 1986 The Law of Deposit Insurance was amended so as to extend DIC’s capacity to giving subsidy to those banks that absorbs failed banks. 1992 DIC operated for the first time since its establishment to bail out a small regional mutual banks. 1995 DIC reform under consideration. DIC had two duties: ¥10 million per July depositor payout should a bank fail, help facilities M&A between troubled banks and healthy banks. 1995 First postwar bank collapse (Hyogo Bank) and Kizu Credit Cooperative Sept. was also shuttered after a run on deposits. Commitment of DIC funds to these schemes depleted its coffer, requiring it to draw on a ¥500 billion credit line from BOJ. 1996 The insurance premium rate was increased sevenfold. At the same time, the government promised to keep unlimited compensation through March 2001. 1997 The DIC begins taking a larger role in bank rescues by taking problem loans from failed banks. Later in the year the LDP vowed to introduce the so-called ‘payoff’ system, capping compensation at ¥10 million per deposit account, and raised the DIC’s BOJ’s borrowing limit to ¥10 trillion from ¥2 trillion. 1998 The MOF outlines a planned legislative change aimed at, among other Jan. things, ensuring full deposit repayments in the event of bank failure till the end of March 2001. 1999 LDP decides to extend for another year the deposit insurance system. Dec. 2002 Step one of deposit insurance reform is enacted. The government limits April payoff for time deposits at ¥10 million. (Source) Financial Services Agency 41 References Aoki, Masahiko. 1994. "Monitoring characteristics of the main bank system: An analytical and developmental view," in Aoki, Masahiko and Hugh Patrick (1994), 109-41. Aoki, Masahiko and Hugh Patrick (eds.), The Japanese Main Bank System: Its Relevancy for Developing and Transforming Economies, Oxford University Press: New York. Baums, T. 1994. “German banking system and its impact on corporate finance and governance.” In M. Aoki and H. Patrick (1994), 409-49. Bodenhorn, Howard. 2001. “Short-term loans and long-term relationships: Relationship lending in early America.” NBER Working Paper Series, Historical Paper 137. Calomiris, Charles W. 1999. “Building an incentive-compatible safety net.” Journal of Banking and Finance 23, 1499-520. Campbell, T., and W. Kracaw. 1980. “Information production, market signaling, and the theory of intermediation.” Journal of Finance 35, 863-82. Edwards, Jeremy, and Klause Fischer. 1994. Banks, Finance and Investment in Germany, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Fukao, Mitsuhiro. 2001. “Financial deregulations, weakness of market discipline, and market development: Japan’s experience and lessons for developing countries.” Paper presented at the IDB-JCIF Workshop Japan’s Experience and Implications for Latin America and the Caribbean, June 2001. Hamada, Koichi, and Akiyoshi Horiuchi. 1986. “Political economy of the financial system,” in Kozo Yamamura and Yasukichi Yasuba (eds.), The Political Economy of Japan, vol. 1, The Domestic Transformation, 223-260, Stanford University Press. Hanazaki, M., and A. Horiuchi. "Is Japan's financial system efficient?" Oxford Review of Economic Policy 16 (2), 2000. Hanazaki, Masaharu and Akiyoshi Horiuchi. 2001. “The ups and downs of the financial system in postwar Japan: Evidence from the manufacturing sector.” A paper presented at NBER/CIRJE/EIJS/CEPR Japan Project Meeting held in 42 Tokyo on September 14-15, 2001. Hellwig, M.F. 1989. “Asymmetric information, financial markets, and financial institutions,” European Economic Review 33, 277-285. Horiuchi, Akiyoshi and Katsutoshi Shimizu. 1998. “The Deterioration of Bank Balance Sheets in Japan: Risk-taking and Recapitalization,” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 6, 1-26. Hoshi, T., A. Kashyap, and D. Scharfstein. 1990. “The role of banks in reducing the costs of financial distress in Japan.” Journal of Financial Economics 27, 67-88. Hoshi, T., A. Kashyap, and D. Scharfstein. 1991. “Corporate structure, liquidity, and investment: Evidence from Japanese industrial groups.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 33-60. Kroszner, R.S., and P.E. Strahan. “Bankers on boards: Monitoring, conflicts of interest, and lender liability.” NBER Working Paper Series 7319, 1999. Petersen, M.A., and R.G. Rajan. “The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (12), 1995, 407-43. Prowse, Stephen D. 1992. "The structure of corporate ownership in Japan," Journal of Finance 47, 1121-1140. Rajan, R.G. “Insiders and outsiders: The choice between relationship and arms-length debt.” Journal of Finance 47, 1992, 1367-400. Rajan, Raghuram G. 1998. “The past and future of commercial banking viewed through an incomplete contract lens.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 30 (3), 524-550. Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 2001. “Financial systems, industrial structure, and growth.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 17 (4), 467-482. Saunders, Anthony. 2000. Financial Institutions Management: A Modern Perspective 3 rd Edition. The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. Sharpe, S. 1990. “Asymmetric information, bank lending and implicit contracts: A stylized model of customer relationships.” Journal of Finance 45 (4), 1069-87. Sheard, P. 1994. “Main banks and the governance of financial distress.” In 43 Masahiko Aoki and Hugh Patrick (1994), 188-230. Stiglitz, J.E. 1985. “Credit markets and the control of capital.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 17 (2), 133-52. Stiglitz, J,E., and A. Weiss. 1981. “Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information,” American Economic Review 71, 393-410. 44