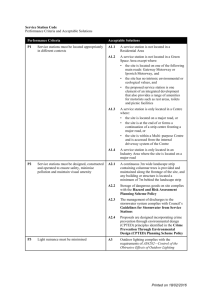

International Congress of Aesthetics 2007

advertisement

Graffiti Scene Katja Jordan, Faculty of Humanities Koper, Slovenia Introduction Imagine a city where graffiti wasn't illegal, a city where everybody could draw wherever they liked. Where every street was awash with million colors and little phrases. Where standing at the bus stop was never boring. A city that felt like a living breathing thing which belonged to everybody, not just the estate agents and barons of big business. Imagine a city like that and stop leaning against the wall – it is wet.1 Graffiti - as a form of a wider phenomena of street art2 developed in the contex of the urban enviroment and became an indispensable part of it. Graffiti is a type of deliberately inscribed marking made by individuals on surfaces, both private and public. It can take a form of drawings, words or - even art. It is contradictory that I am talking about art that actually does not want to be art. There is no “lyric subject”, no “metaphysical considerations”. And even the interested professional and intelectual public has trouble following this kind of art3. Nevertheless, I am going to use the term “Graffiti art” according to a specific group of graffiti: stylised signatures and other inscriptions, known as writings, made by hand with sprays, markers, chocks, etc. This group of graffiti differs from other wall statements, images and depictions (stencils, signatures and comments) by their fine art execution and their incorporation within the iternal system of working crews and the rules defining the graffiti subculture. It is classified as art and this terminology technically defines that which could be considered as having aesthetic attributes.4 I will focus on Slovenian graffiti scene. Since Slovenia captures small geographical space it is very interesting and challenging to follow recent street art appearances. Therefore, graffiti Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper apper in cities across the country and it is not surprising that writings of specific (few) authors turn up in almost all Slovenian towns and cities.5 Graffiti art Graffiti art is in its essence illegal, unannounced, non-profit and provocative. It appears in public places, the space in private or state possession. The street represents an exhibition place and graffiti art is not just for certain group of people, but for general public. For its existence it does not require any praise or support of art institutions. By bringing “artworks” outside the traditional context of museums and galleries, this kind of action provides increased access to the art of our time and provides artists with a unique opportunity to expand their artistic practice. It is art for the public, even though the public hadn't requested it. Many contemporary analysts and even art critics have begun to see artistic value in some graffiti and to recognize it as a form of public art. And according to many art researchers that type of public art is, in fact an effective tool of social emancipation or in the achievement of a political goal. Graffiti art began in 70’ in New York. That being the case, it was not all surprising that when the youth in other parts of the world became aware of what their counterparts in NY had been up to for years, they were quick to try their hand at spraycan art. Graffiti practicly boomed out of nowhere. Two trends have emerged since the art world embraced grafitti in the early eighties. One trend was that, those writers who joined the establishment art scene began to respond to the influence of dealers, collectors, and other artists, and they discovered other motives to produce their art. They evolved as artists, their work becoming in some ways more complex, more subtle, and at the same time more appealing to collectors in the fast moving art world. These artists have often lost sight of their original public, retaining only the use of the spraycan as a tool. The second trend is the grafitti as a way of communitation between young people in the (hip hop) subculture. Probably the greatest agent for spreading this art form was the hip hop explosion of the eary eighties. The work of art came to be seen as a communicative exchange. As a result, the concept of autonomy of art was replaced by the concept of intertextuality. 2 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper When streets communicate Graffiti is unique and inexpensive form of communication. The bearers of information are words and images. But the information is primarily artistic and, as such, not so easily comprehended by the general public. Graffiti art lives in a world of its own with its own language and it behaves according to its own rules. Graffiti art aims at self-expression and creativity, and may involve highly stylized letterforms drawn with markers, or cryptic and colorful spray paint murals on walls, buildings and trains. Graffiti artists strive to improve their art, which constantly changes and progresses. Graffiti is subject to different societal pressures from popularly-recognized art forms, since graffiti appears on walls, freeways, buildings, trains or any accessible surfaces that are not owned by the person who applies the graffiti. This means that graffiti forms incorporate elements rarely seen elsewhere. Spray paint and broad permanent markers are commonly used, and the organizational structure of the art is sometimes influenced by the need to apply the art quickly before it is noticed by authorities. If we want to understand graffiti, we have to understand the processes that lead to it. Here are a few of the fundamental features: graffiti is made largely by people without a whole lot of money for supplies. Spray paint is the medium because it’s fairly cheap or shoplift able (which gets harder and harder and hence presents more and more of a challenge). And spray paint is the medium also because you can create large and visible forms quickly, which is obviously desirable when your point is to be seen and when the cops might be coming. 6 Crispin Sartwell says that if we really want ot understand the medium of graffiti, we have to start with its illegality. He claims that the procces of making this art illegally has to be “particulary absorbing”7. It involves concealment, sneaking around in the dark while avoiding the authorities: in short, the medium is risk, whereas so much art involves no risk. Graffiti is of necessity an adventure. It involves running, infiltration, escape.8 3 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper It is an action, filled with adrenalin. According to Roger Gastman graffiti writers have serious problems with obsession and addiction. But he claims that both of these characteristics are required to “advance and thrive in the game of graffiti”.9 Graffiti is an expression of creative individuals with their own convictions, voices and desires. Actions of graffiti artists are very important in this context. Graffiti are made late at night when most people are a sleep. This kind of actions invests graffiti art with certain charm and sharpness. Graffiti cannot be compared with classical painting. The making of graffiti depends on outside factors (cameras, guardians…), which have to be taken into account before the action in order to eliminate the possibility of failure. The skill of graffitists could be judged on the basis of the information they possess about the conditions of work. Writing at locations that are difficult to access, or highly secured, increases the importance and status of a graffitist. Graffitists work “undercover”. They create new names; they sign their work with nicknames, initials, and coded identities. Since the ilegal situation forces them into secrecy they have to live double lives. It is almost necessary to create a new identity. Often the name acts as main motiv of artistic process. Name is very important and represents one of the most common of all forms of graffiti.10 Most frequently the massages are the pseudonyms of artists, while their meaning and presence at all possible corners are comprehensive merely to members and connoisseur of this particular subculture. Classifications of graffiti I will briefly go through main classifications of graffiti. First one is tagwhich is a stylized signature; the terms tagger and writer refer to a person who "tags". A tag can be distinguished from a piece by its relative simplicity. Tags are usually comprised of a single color that contrasts sharply with its background. Tag can also be used as a verb which means "to sign". Writers often tag their pieces following the tradition of signing masterpieces. Then is a throwup which is defined by the short amount of time it takes to create, a throw-up is not a piece. It generally consists of an outline (like black) and one layer of fill-color (like silver). Throw-ups are often utilized by writers who wish to achieve a large number of tags while competing with rival artists. The short amount of time it takes to complete a throw-up reduces the risk of getting caught. The most valuable within the subculture is a piece (from "masterpiece"). It is a 4 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper large image, often with 3-D effects, arrows giving flow and direction, with many colors and color-transitions and various other effects. A piece needs more time to be executed than a throw-up. If placed in a difficult location and well executed it will earn the writer more respect. Piece can also be used as a verb that means: "to write". Competition exists between writers as to who can put up the most, or the most visible or artistic graffiti. Writers with the most tags, throw ups and pieces up tend to gain more respect among other graffiti artists, although they will also incur a greater risk if caught by authorities. As well as being prolific, writers are also expected to have "style", which means their work is artistic and accomplished. Other works covering otherwise unadorned fences or walls may likewise become so highly elaborate that property-owners or the government may choose to keep them rather than cleaning them off. "Free walls" or commissioned walls are now a common part of the culture. Graffiti are not generally considered as artwork. Presumably they belong to the world outside art, the world nearer to visual culture, that is to say, to omnipresent visual images of the media, fashion, television, commercial film and digital worlds. Graffiti also “jumped« from one cultural context into another. This happened several decades ago and is evidenced in the different creative paths of two American artists, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jonathan Borovsky. Jean-Michel Basquiat came from the new wave that broke in fashion, styling, music and graffiti in New York in the late 1970s. Wild Style, a film by Charlie Ahearn from 1982, documented the rap and hip-hop scenes of the South Bronx and the Lower East Side. That was the time when the most renowned graffitists of the New York subway, artists like Lee Quinones, Futura 2000, Daze, A-One and Crach, had already given up their battle with the New York Transit Authority and started to make sponsored works in school yards, parking lots and salable canvases11. Basquiat first became famous as Samo. This was his tag. That was how he and Al Diaz used to sign their cryptic massages and crude drawings on the walls of Soho, always adding the copyright mark © and frequently also a stylized crown. Then, sometime in 1980s, Samo was killed off and Basquiat showed up. With the help of Keith Haring, who came out of the same scene, he started to exhibit in clubs. In 1981 he signed a contract with the eminent New York 5 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper gallerist Annina Nosei, agreeing to deliver his paintings on canvas in exchange for payment in money and materials. This act announced the following year: within one week he managed to open his first personal exhibition in the Mary Boone Gallery, one of the most influential galleries of the time, to be included in an overview prepared by the Museum of Modern art in New York, and to be presented in the Times magazine. He was 24 when the prices of his canvases reached the values of the Renaissance masters12. By the second half of the 1970s, Borovsky already had held a number of exhibitions in prominent galleries in the U.S.A., frequently drawing or painting directly onto the gallery walls. He worked with the help of a projector, which transmitted images precisely in the required size from transparent sheets of paper onto walls. His work expressed the dichotomies between male and female, the inner self and the outer world, the two halves of the brain, and the different kinds and qualities of communication. In 1982 he was invited to Berlin to participate in the cult Zeitgeist exhibition. His first idea was to blow a hole in the Berlin Wall as a part of exhibition. The Zeitgeist exhibition took place in the building formerly occupied by the Gestapo, within meters of the Berlin Wall. The wall divided the city in two parts and expressed a dichotomy, which was a subject of the artist’s work. The blasting of the wall was not meant to be an artistic performance, but rather an event that would be in the newspapers next day. Borovsky knew some people who could supply him with the explosives. As the action was highly unpredictable – it was hard to predict the moment when there would be no people on the other side and the explosion would not harm anybody – Borovsky finally gave up the idea. He decided to make his own graffiti on the wall, which was already full of them. He made an image of a giant naked man on the run, which also symbolized escape, just as the hole in the wall would13. Borovsky and Basquiat examples show that graffiti became a part of art in different ways. Basquiat’s success brought them from visual culture in to art. Differently, Borovsky gave to art wall paintings a dimension of visual culture. Both phenomena point to the fact that the borders between art and visual culture, in other words, between high and low art, or cultivated and folk creativity are penetrable. The appropriation of subculture was made possible by changes that occurred in the context of the high art world. In the U.S.A. this process had already begun in the 1970s, when the creative forms of deprived ethnic and social groups started to acquire an equal standing within the world of art, which only heightened its political engagement14. 6 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Graffiti in the streets, both as paintings or inscriptions, form a part of public art. They confirm and, at the same time, deny the characteristics of this specific practice of art expression. Public art is a complex phenomenon. It is a kind of art that literally and figuratively is accesible to anyone. One does not need a premision to look at public monuments, and the evaluations of everybody, including those not specialised in monuments, have the same weight in the creation of the opinion of wheather a monument is good or bad. Public art shows itself in various forms – as artful flower beds, fountains, monuments, memorials, sculptures, media art projects, billboard projects, Internet art, site-specific instalations, street theatre, etc. Besides these forms there is also new public art denoting various actions – socalled actionism – by artists in local communities, aimed at meeting the inhabitants and solving their local problems. Public art thus comprises traditional representation, as well as more recent art forms, on/in public spaces and public communication networks. These latter, for example media art projects (billboards, newspaper and magazine projects, Internet art), are tightly connected with visual culture. Both traditional and public art is contained in the complex social tissue. This dependance on different sectors of society is expressed by the meanings of the syntagma “public art”. Public art is not necessary created with a commission but also without a commission of authorities responsible for managing of the public spaces. In the ’90 the citizens of Amsterdam noticed that, every now and than, someone had put a new small sculpture of a men on a tronck of tree in small park, and for a long time they couldn’t find out who was making and placing them there. To put in other words, public art as a cultural phenomenon is defined by the complex legal, economic and social contents of the public.15 W.J.T. Mitchell in his book Picture theory in an article , The violence of public art: Do the right thing in the beginning is putting an example of statue of Mao Tse Tung in Beijing University campus, where the thirty-foot molotih was enveloped in a bamboo scaffold “to keep the harsh desert winds” – and not much later the same thing happened in university campuses all over China. One year later, newspapers around the world published (’89) photos of Chinese students erecting a thirty-foot plaster “Goddess of democracy” directly facing the disfigured portrait of Mao in Tinanmen Square despite the warnings by government that it is an illegal statue. That it is not improved by government... A few days later an army of tanks was moving down this statue along with thousands of protesters… 7 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Mitchell says that in public art there is high political and legal control, not only for the erection of public statues and monuments, but over the display of a wide range of images, artistic or otherwise, to actual or potential public. And further on he says, “public ness” of public images goes well beyond their specific sites or sponsorship: publicity has, in a very real sense, made all art into public art. And art that enters the public sphere is liable to be received as a provocation to or an act of violence.16 We should not look at graffiti art naively and superficially. Its contents and meanings are not found only in its fine art fascination and the literal translation (deciphering) of signs. Graffiti narrates a story of the time and space in which it is being created. The current times are marked by the growth of the new economy, globalisation, the money system and increased state security in the public and private sectors, which justifies omnipresent video surveillance. Long working hours and the abolition of leisure, individual rights and identity are only a few consequences of the capitalist system in which we live. With their financial monopolies, multinational and other wealthy companies and institutions buy media space and use it to manipulate human needs, time and belongings by means of announcements and advertisements. State authorities find nothing wrong with the violent spread of hoardings of all kinds and sizes, and a regular citizen looks at it as a self-evident process. Propaganda and graffiti share a common space and manner of representation – only that the latter is illegal, while the advertisements are treated as protected private property. Think about the appearance of advertising in public places. It's everywhere, and though sometimes it's clever or subtle or artistic, more often it's puerile and stupid and it hurts the eye. If you have money, you can put up your tag everywhere, all the time, in all media, from the billboard to the vehicle to the pop-up ad, from buses and buildings to television screens and magazines, from public parks to huge skyscrapers shaped like your logo. Money brings with it an absolute right to convey your message and your name and your image to everyone, to completely dominate space of all kinds. This is an effect, we might say, of this motherfucker called capitalism - it brings with it an effective control of public discourse. Speech is free in the sense that it is more or less protected by the Constitution; it is not free in the sense that it costs money. 17 8 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Graffiti in Slovenia The development of graffiti scene in Slovenia goes back to the eighties. Slogans and inscriptions appeared on streets, but were successfully barred from the streets by the authorities of the time.18 At first punks wrote them, mostly on walls of places where they gathered19. And along whit this textual graffiti, graffiti as paintings also started to emerge. In 1983 the St Urh’s exhibition of graffiti was organized in the “new” FV Disco premises in the Zgornja Šiška Youth Center. The R Irwin S group prepared the exhibition; working from a book of photographs showing the killings of partisans at St Urh’s church during World War II, they painted graffiti on the walls around the dance floor. A bit later on same group prepared a new exhibition – of “erotic graffiti”.20 These graffiti were influenced by the American graffiti art in terms of formal point of view, but their iconology was entirely different. At the end of 1980s a group Stip Core believed that graffiti could be art and in addition to wall graffiti they painted graffiti on canvases, wood, metal and cardboard. Several other groups functioned in the 1990s alongside Strip Core: Mizz Art, SK8 Core, Mega Medi Group and, somewhat later, Klon Art Resistance. We can infer from these group names alone that they were organized and creative groups with specific programs, concepts and manners of artistic creation and expression. They were primarily oriented towards the painting of clubs, pubs, studios and design ateliers, and were less active in the domain of graffiti in the streets. The mid1990s was an intermediate period in the development of graffiti in Slovenia. /…/ A younger generation was coming to the forefront whose culture of socializing, creating and expressing themselves was based more on the intense phenomenon of skateboarding and the development on the hip hop scene.21 Graffiti art is well rooted in Slovenia, and in recent years it has received gradual acceptance on various levels. On the one hand, it is worth mentioning Strip Core’s graffiti activity, which has been going on since the end of the 1980s, while in 2000 the Suburban Cakes festival took place in Metelkova, Ljubljana’s “autonomous cultural zone”. On the other hand, there have been organized and sponsored graffiti actions (for instance, the painting of underpasses), as well as a few outdoor murals and well-paintings in bars and cafes; there is a “graffiti bus” that drives around the city; in 2004 Slovenia’s first exhibition of graffiti took place in International 9 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper center of graphic arts. Today graffiti artists present “graffiti lessons” in the afternoon on commercial channel TV Paprika and so on.22 Graffiti art is considered one of the new, fresh and attractive forms of artistic expression in Slovenia. Firstly graffiti was a medium of communication and a challenging design product rather than a work of art. In the second half of the 90s the first international magazines, rare books and graffiti catalogues started to circulate among the young graffitists. In recent years the Internet has become an invaluable source of information, allowing very quick access to fresh news about graffiti. Since 2000 we have been able to talk of the complete spread of graffiti, with artists attributing this directly to the development of the hip-hop scene in Slovenia. Now days we can witness a great development of graffiti scene in Slovenia. There are few groups who work on the streets (Zek Advance Crew, Egotrip, Section 1.3, etc.). Pieces of artists who work alone or in groups can be seen all across Slovenia and also in other countries. Graffiti can be found around the world and street artists often travel to other countries foreign to them so they can spread their designs. Slovenian graffitists Rone84 Rone84 is a very prolific and universal street artist who makes graffiti, stencils, stickers and posters. He developed his characteristic style by familiarizing himself with the history of graffiti and street art. He addresses a very broad public and does so without compromise or too much deliberation; as soon he sees a chance to occupy a space, he takes it and draws attention to his own presence. His work is a kind of parody of mass advertising and decorations with socially acceptable and well-paid visual images that often pollute even our mental environment. 10 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Zek advance This is Ljubljana’s most recognizable group of street artists. One of their most distinctive images is the “bunny” which can be seen in different contexts and derivations. They view their work as play, mockery creative action, or simple branding, such as is typical in advertising and product marketing. Nevertheless, their massages are extremely serious and aimed at the various age groups; in this way, they seek to raise awareness of social issues (the question of building a mosque, fast food restaurants, social restrictions, the treatment of animals, etc.). Zenf Zenf’s street work is related to humor and, on the one hand, a very relaxed view of the surroundings in which he lives and to which he responds. Here we can include images of scales, tubes of mustard and various other stickers. On the one hand, however, he delivers a very critical response in regard to control of the public space by various corporations, security agencies, and similar organizations that use surveillance cameras. His work has lately been focused no a critique of the control rooms in which data from the surrounding area is recorded and archived. He sticks his black-and-white stickers with pictures of surveillance cameras in places where such surveillance is problematic and questionable. Joke42 Joke42 is one of the more recognizable Slovene street artists; his work can be seen in all the larger Slovenian cities. Lately, he has limited his street expression to criticizing the contemporary consumer society, which is driven by the word “shopping”. For him, this word means, on the one hand, a method, on the other, the tempo and speed of life lived in recent years by majority of people who crave buying things. His drawings of empty shopping carts are addressed to the public of the big shopping malls and serve to mark individual stores that have gone out of business. 11 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Conclusion Contents and meanings of graffiti art are not found only in its fine art fascination and the literal translation of signs. Graffiti defiantly narrates a story of the time and space in which is being created. Contemporary graffiti is primarly significant as inter-group communication. Graffiti is a peculiar and inexpensive form of communication created as a response to the growth of highly technological means of communication. Most frequently the bearers of information are word and images. This is an illegal activity often condemned as vandalism, for it invades the space in private or state possession, from architecture to public transport vehicles. It comprises elements of destruction and creation, which results in its temporary nature and the fact that these art forms are constantly changing. The first factor influencing its transitory nature is social intolerance; the second is competition between artists within the movement itself, which appears in tis most radical form as covering and painting over existing graffiti. This art form has its roots in an urge to be seen and being visable to everybody. We should look at graffiti as a constructive critisism of today's society. I will conclude with words by Carolyn Steinat: In urban society where anonymity is increasingly experienced, it becomes important to express the own personality, one's heart and soul by creativity, by creating something distinguished on our own. This is how the graffiti artist attempts to escape from the surrounding anonymity, by the individual art of graffiti marking, which however happens in a group, to create a sort of »homeland« in the jungle of the city.23 12 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Notes and references 1 Banksy, http://www.banksy.co.uk/menu.html, 2005 Street art covers a wide field of grafftiti, posters and stickers, as well as street theatre, dance, etc. 3 Velikonja, Mitja. Streets are saying things. Ljubljana: A Low-Tech Re-Action, 2006 4 Phase 2, http://graffiti.org/faq/mythconceptions.html, 1999 5 Lately the trains are also very popular »target« to paint graffiti on. 6 Sartwell, Crispin. Article about graffiti. http://www.crispinsartwell.com/graff.htm, p.3 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. p.4. 9 Gastman, Roger. Enamelized – Graffiti worldwide. Corte Madera, Bethesda: Gingko Press, R77 Publishing, 2003, p.3. 10 It is a type of graffiti we call it Agnomical. 11 Stepančič, Lilijana. Grafiti kot sodobni spomeniki. In Liljana Stepančič (ed.) Grafitarji Graffitists, Ljubljana, MGLC, 2004, p.12 (from now on abbreviated ad GG). 12 Nairen, Sandy. State of the Art: Ideas and the Images in teh 1980s, London: Chatt & Windu Ltd, 1987 13 GG, p.15. 14 GG, p.16. 15 Mitchell, W.J.T.. Picture theory, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994, p.371. 16 Mitchell, W.J.T.. Picture theory, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994, p.370. 17 http://www.crispinsartwell.com/graff.htm 18 Zrinski, Božidar. Grafitarji/Graffitists (2004): Mojstrovine Masterpiecies. In Liljana Stepančič (ed.) Grafitarji Graffitists, Ljubljana, MGLC, 2004, p.46 (from now on abbreviated ad MM). 19 Basement premises of the Ljubljana FV Disco. 20 MM, p.46. 21 MM, p.52. 22 Velikonja, Mitja. Streets are saying things. Ljubljana: A Low-Tech Re-Action, 2006, p.2. 23 Steinat, Carolyn. Thought about the tearing down of the »schlachthof« area in Wiesbaden. http://www.graffiti.org/faq/steinat.html 2 13 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper Literature & References: Ganz, Nicholas (2004): Graffiti World: Street art from five continens, Thames&Hudson, London Mednarodni grafični likovni center, Grafiti kot sodobni spomeniki, 2004, Ljubljana Cooper, Martha in Chalfant, Henry (1996): Subway art, London Christ, Thomas (1984): Subway Graffiti, New York 82,83; Basel Britannica Encyclopedia of Art 2005, The Brown Reference Group, London Abel, Ernest L., Buckey, Barbara E. (1977): The writing on the wall: Toward sociology and psychology of graffiti. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut. Stensili, posterji in stikerji, A Low-Tech Re-Action (2006), Ljubljana Kolomančič, Petra (2001): Fanzini - Komunikacijski medij subkultur. Frontier 015. Maribor, Subkulturni azil Gržinič, Marina, Erjavec, Aleš (1991): Ljubljana, Ljubljana. Mladinska knjiga, Ljubljana Velikonja, Mitja. Streets are saying things. Ljubljana: A Low-Tech Re-Action, 2006 Gastman, Roger. Enamelized – Graffiti worldwide. Corte Madera, Bethesda: Gingko Press, R77 Publishing, 2003. Nairen, Sandy. State of the Art: Ideas and the Images in teh 1980s, London: Chatt & Windu Ltd, 1987 Mitchell, W.J.T.. Picture theory, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994. http://www.banksy.co.uk/menu.html http://graffiti.org/faq/mythconceptions.html http://www.crispinsartwell.com/graff.html http://www.graffiti.org/faq/steinat.html 14 Katja Jordan, Faculty of humanities Koper 15