Paper on LLPs and section 235 FSMA

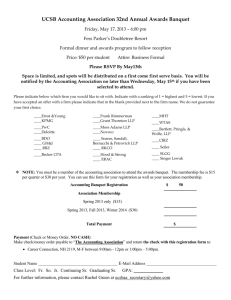

advertisement

The Impact of Section 235 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”) on Limited Liability Partnerships (and other partnerships) 1 Introduction 1.1 The question which is considered in this paper is whether a limited liability partnership (LLP) which is formed for the purpose of carrying on a business1 other than an investment business could be a collective investment scheme within section 235 of FSMA (“cis”) and, if so, what the consequences are. The question is also relevant in relation to general and limited partnerships. 1.2 Section 235 of FSMA is based on section 75 of the Financial Services Act 1986. It defines a collective investment scheme in very broad terms but the impact of the section is curtailed by a number of exemptions which are contained in SI 2001/1062 as amended (“the CIS Order”) which was in turn based on certain exclusions contained in section 75(5) to (7) of the Financial Services Act 1986. The issues raised in this paper are therefore not new and have existed since section 75 of the 1986 Act came into force. However, the issues are relatively new so far as concerns LLPs formed in Great Britain since such LLPs have only been capable of being formed since 6 April 2001. 1.3 Although the word ‘investment’ is used in the expression ‘collective investment scheme’ it does not appear elsewhere in section 235. In addition, there is no general exemption in the CIS Order for entities which are established for the purpose of carrying on a business which is not an investment business. There is an exemption for bodies corporate but this expressly does not apply to an LLP. There is also an exemption for schemes entered into for commercial purposes related to an existing business which is considered further below. 1.4 Where an LLP is set up for the purpose of carrying on a business it is necessary, in the absence of an applicable exemption in the CIS Order, to determine whether it may be caught by section 235. As mentioned above the same issues broadly arise in relation to both general and limited partnerships. 2 The Definition of a Collective Investment Scheme 2.1 Section 235 provides a cumulative test for a collective investment scheme (“cis”). Sub-section (1) defines a cis as ‘any arrangements with respect to property of any 1 ‘Business’ is defined in section 18 of the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 as including every trade, profession and occupation. 1 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 description, including money, the purpose or effect of which is to enable persons taking part in the arrangements (whether by becoming owners of the property or any part of it or otherwise) to participate in or receive profits or income arising from the acquisition, holding, management or disposal of the property or sums paid out of such profits or income. 2.2 Sub-section (2) provides that the arrangements must be such that the persons who are to participate (“participants”) do not have day-to-day control over the management of the property, whether or not they have the right to be consulted or to give directions. 2.3 Sub-section (3) provides that the arrangements must also have either or both of the following characteristics: (a) the contributions of the participants and the profit or income out of which payments are to be made to them are pooled; (b) the property is managed as a whole by or on behalf of the operator of the scheme. 2.4 Before analysing the constituent parts of section 235 it is worth noting that the principal regulatory consequences of an LLP or a partnership constituting a cis are twofold. First, the establishment, operation and winding up of a cis are regulated activities if carried on in the UK by way of business and secondly the financial promotion restriction will apply to any invitation or inducement to acquire or dispose of an interest in the LLP or partnership, subject to the exemptions contained in SI 2005/1529 (“the Financial Promotion Order”) in the case of a financial promotion made by an unauthorised person or SI 2001/1060 as amended (“the CIS Promotion Order”) in the case of a financial promotion made by an authorised person. 2.5 As regards the first consequence, article 3 of SI 2001/1177 provides that a person is not to be regarded as carrying on by way of business one of the activities specified in that article (which include operating a collective investment scheme) unless he carries on the business of engaging in one or more such activities. The effect of this Order is considered further in paragraph 4.2 below. 2.6 Turning to sub-section (1) of section 235, it would appear that an LLP or a partnership would prima facie be caught by its wide wording regardless of the type of business which it carries on. The term “arrangements” is clearly wide enough to cover a partnership or an LLP. Were that not the case there would presumably have been no need to exempt all bodies corporate from the section (see article 21 of the 2 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 CIS Order). In the case of an LLP or a partnership, the arrangements would be the LLP or the partnership itself and any agreement between the members. The “property” concerned could be any of the property of the LLP or the partnership including monies subscribed to it by way of capital or even its goodwill. In the case of an LLP, as opposed to a partnership, it is the LLP rather than its members which will ordinarily own the property concerned but this appears to be immaterial as regards section 235 because the members of the LLP can be participants even though they are not owners of the property or any part of it but only have an indirect interest via their interest in the LLP (having regard to the words “or otherwise” in sub-section (1)). Again, if this were not the intention, there would have been no need to exempt all bodies corporate from this section in article 21 of the CIS Order. 2.7 There remains the question of whether the purpose or effect of the arrangements fall within the wording of this sub-section. It is worth noting that the test to be applied is a purpose or an effect based test. So, regardless of the purpose of the arrangements, if the effect of them is that the participants receive income arising from the acquisition, holding, management or disposal of the property the test is satisfied. In the case of an LLP or a partnership which is established to carry on a business of any kind it seems that this test could be satisfied in a number of ways. If any of the capital or other property of the LLP/partnership generates income which is distributed to the members/partners the test would appear to be satisfied. If all the income of the LLP/partnership derives exclusively from the selling of goods or services it might still be argued that its income derives to an extent from the ‘holding’ or ‘management’ of its goodwill so as thereby to satisfy the requirements of this sub-section. If this goodwill argument does not stand up, an LLP or a partnership whose income is derived exclusively from selling goods or services might escape the net cast by this sub-section but what if a small proportion of its income is derived from placing surplus funds on deposit with a bank? It is not clear that a de minimis rule could be invoked and accordingly it may be arguable that the receipt of only a small amount of interest would be sufficient to satisfy the test in this sub-section. It might, per contra, be possible to argue that the receipt of such interest (or other income derived from assets of a trading LLP/partnership, such as sub-rental earned on premises which are surplus to requirements) is not the purpose of the arrangements with respect to property but it would be more difficult to argue that it was not the effect of the arrangements. A further argument might be that section 235 should be the subject of a purposive rather than a literal construction and that it is necessary to look at the substance of the arrangements 3 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 when looking at their purpose or effect. However, the success of such an argument must be uncertain. 2.8 Sub-section (2) concerns day-to-day control over management of the property concerned. It appears from the decision in Russell-Cooke Trust Co v Elliott, an unreported decision of Laddie J on 16 July 2001, that all the participants must have day-to-day control of the property. While in theory it might be possible, in the case of a limited partnership, for the limited partners to have day-to-day control of the management of the business of the partnership without exercising it and thereby losing limited liability, there must be a risk that a court would not regard them as having any real right to control the day-to-day management in the absence of any intention to exercise it. In the case of a general partnership or an LLP, while it might be possible in the case of a small firm for all the members to have day-to-day control of the management of the partnership property, including its bank account, firms of any size will find this impracticable and will in practice delegate management to a managing partner or member or a small committee of partners or members. In these circumstances there will be doubt as to whether the partners or members as a whole have retained day-to-day control over management of the property of the firm. 2.9 It is clear from section 235(2) that where there is a delegation of management to a manager or management committee, the right of the partners or members as a whole to be consulted or to give directions will not be sufficient to constitute day-today control over management of the property of the firm. We understand that Leading Counsel has advised at least one major law firm that, in these circumstances the question of whether the participants as a whole have in fact retained day-to-day control over the management of the firm’s property will depend on the extent to which the manager or managers have entrenched rights to manage. Where the partners or members retain the ability to remove the manager or managers summarily or to remove the management functions from the persons concerned and to delegate such functions to another person or persons, it might be arguable that the partners/members as a whole have retained day-to-day control over the management of the firm’s property. However, even if this argument is correct, there will be other firms where the manager cannot be summarily removed by the partners/ members and in those cases it would be difficult to argue that the firm was not a cis on the ground that it does not satisfy the test in section 235(2). 2.10 Sub-section (3) sets out two alternative requirements. In most LLPs/partnerships it seems that the first requirement will be satisfied i.e. the contributions of the 4 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 members/partners and the profits or income out of which payments to the members/partners are to be made will be pooled. In the case of an LLP this will almost invariably be the case because the assets of the LLP belong to the LLP and the profits will only become a debt due the members when they are divided among the members. On the basis that this test is likely to be satisfied in the case of most LLPs/partnerships there is no need to consider the second, alternative, test imposed by this sub-section. 3 The CIS Order 3.1 Turning to the CIS Order, there is one exclusion which might be thought to afford assistance in the particular circumstances where a partnership carrying on an existing business is converted into an LLP, namely that contained in article 9.This provides that arrangements do not amount to a cis if each of the participants (a) carries on a business other than the business of engaging in a regulated activity of the kind specified in the article; (b) enters into the arrangements for commercial purposes related to that business. If the business of the relevant partnership or LLP is wider than that constituted by the arrangements relating to the property which gives rise to the possible existence of a cis, it could be argued that, for both existing and newly admitted partners/members, the arrangements would be entered into for the purposes of a business which commenced contemporaneously with becoming a partcipant in the cis but which was not limited to that resulting from their participation in the arrangements (see article 9(2) of ther CIS Order). If this were the case, the exclusion might apply not only to the existing arrangements in the case of a partnership but also to the conversion of the partnership to an LLP if the conversion were for commercial purposes related to its business. However, if the partnership which is converted into an LLP were itself a cis for some reason, it would be illogical if this exclusion were to apply upon the conversion of the partnership to an LLP and it may be that this exclusion is limited to the circumstances where the existing business continues to be carried on after the arrangements are entered into. If that is the case it is difficult to see how this exclusion could apply where the partnership business is wholly taken over by the LLP. 5 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 4 The Problem 4.1 If an LLP or a partnership which carries on a business other than investment business does constitute a collective investment scheme under section 235 what are the practical implications? 4.2 The first question to consider is whether the managing partner or partners need to be authorised on the ground that they are operating a collective investment scheme. In most cases the answer will be no. Article 1 of SI 2001/1177 provides that a person is not to be regarded as carrying on by way of business an activity to which this article applies unless he carries on the business of engaging in one or more such activities. The activities in question include operating a collective investment scheme. In the normal situation where an LLP or a partnership is managed by one or more managing partners, it seems reasonable to conclude that the managing partner or partners will not be carrying on the business of engaging in regulated activities. However, if an external professional manager were to be appointed to manage a firm it is possible that he would be required to be authorised (although this is unlikely to be the case if he were employed by the firm as opposed to being self-employed). This would be nonsensical for a number of reasons. First it is not necessary for investor protection purposes. Secondly, it is unlikely that such a manager would be willing to take on the job if he had to be authorised. Thirdly, the existing regulation of authorised persons is not geared to regulating such persons. 4.3 The second question which arises for a firm which constitutes a cis is what is the impact of the financial promotion restriction in section 21 of FSMA. Inviting someone to become a member of a firm which constituted a cis would amount to a financial promotion. It might be possible in many cases to place reliance on article 28 or 28A of the Financial Promotion Order but there are difficulties with these exemptions. In particular the conditions in article 28A(2)(b) and (c) may not be satisfied in all cases2. An executive recruitment firm which contacted Mr X with a view to recruiting him to become a member of Firm Y might be surprised to learn that it had committed a criminal offence by doing so. Likewise Firm Y might be surprised to be told that the partnership agreement to which Mr X has subscribed is unenforceable against Mr X and that he is entitled to a return of his capital together with interest (unless a court orders otherwise). 2 In the case of a financial promotion by an authorised person the relevant exemptions are those contained in article 15 or 15A of the CIS Promotion Order. 6 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005 5 Conclusion 5.1 It can never have been intended that section 235 FSMA would to apply to a normal partnership or an LLP which is established to carry on a business other than investment business. If such a partnership or LLP does constitute a collective investment scheme as a result of the very wide wording of section 235 FSMA, this can give rise to practical problems. We therefore consider that a new exclusion should be made in order to clarify the law in this area by providing that arrangements which have as their primary purpose the carrying on of a business other than investment business do not constitute a cis. 5.2 However, it is necessary to recognise that some trading LLPs or partnerships may, now or in the future, have passive investors as members. If such LLPs/partnerships were excluded from being collective investment schemes they would not then be restricted by section 21 of FSMA from inviting third parties to become non-working members and interests in them could be marketed without restriction. This would be undesirable. Accordingly, the financial promotion restriction should apply to interests in such LLPs or partnerships but only where they are marketed to persons other than an existing or prospective working member of the firm concerned. [16] August 2005 7 BLP1.3297774.07.PLG/_PERS/_PERS 16.8.2005