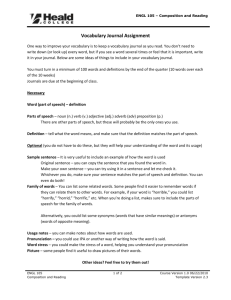

ENGL 120: College Composition II

advertisement